14 Oct 2019

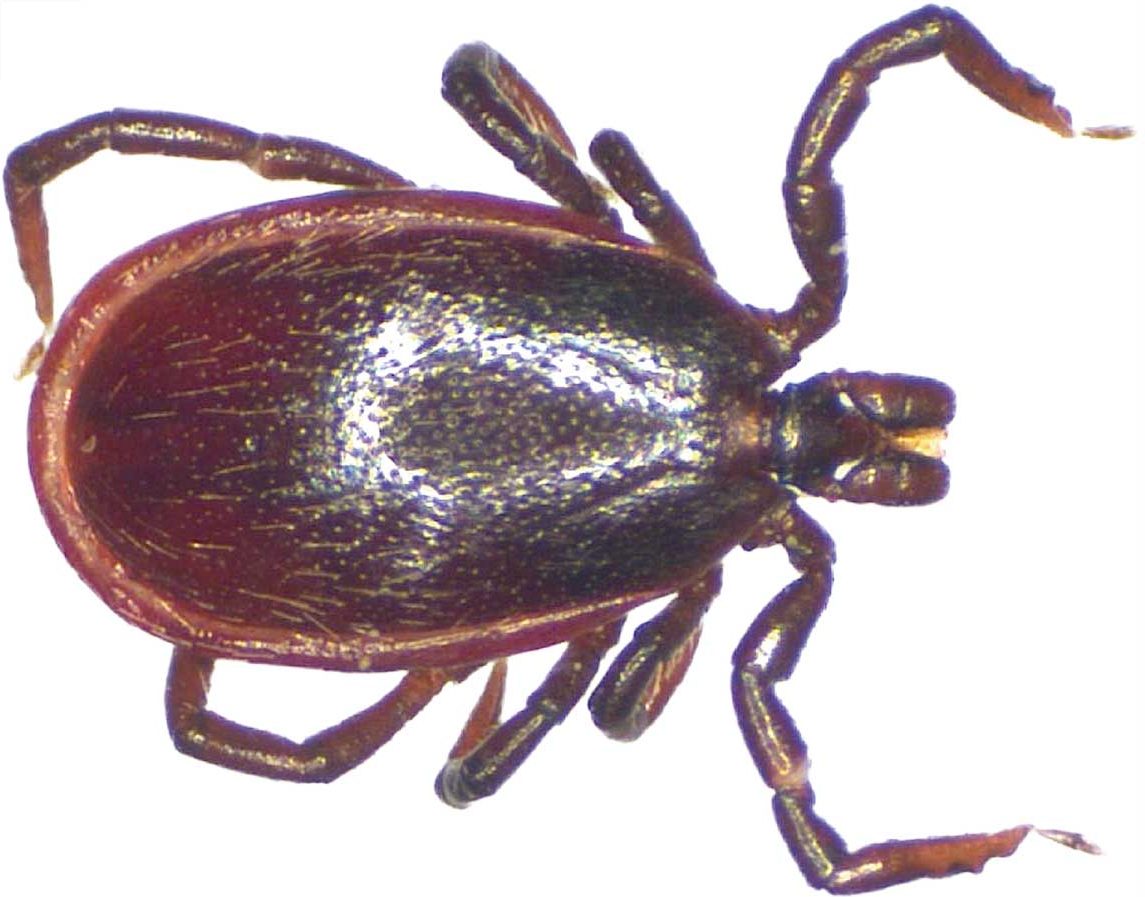

Fleas and ticks – year-round protection and reluctant owners

Hany Elsheikha delves into the new trends in flea and tick control, and discusses the importance of engaging clients.

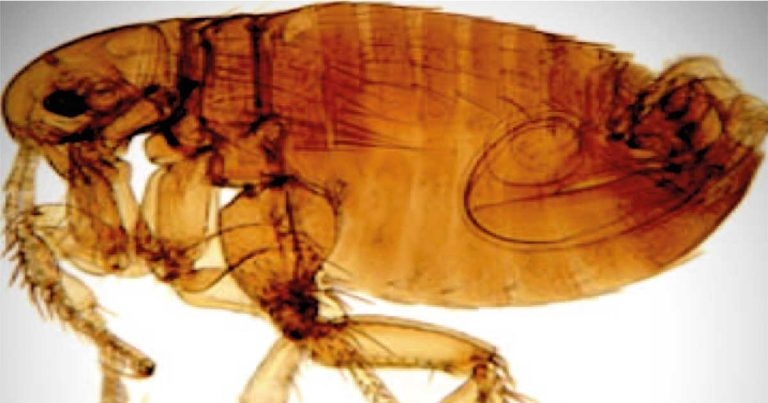

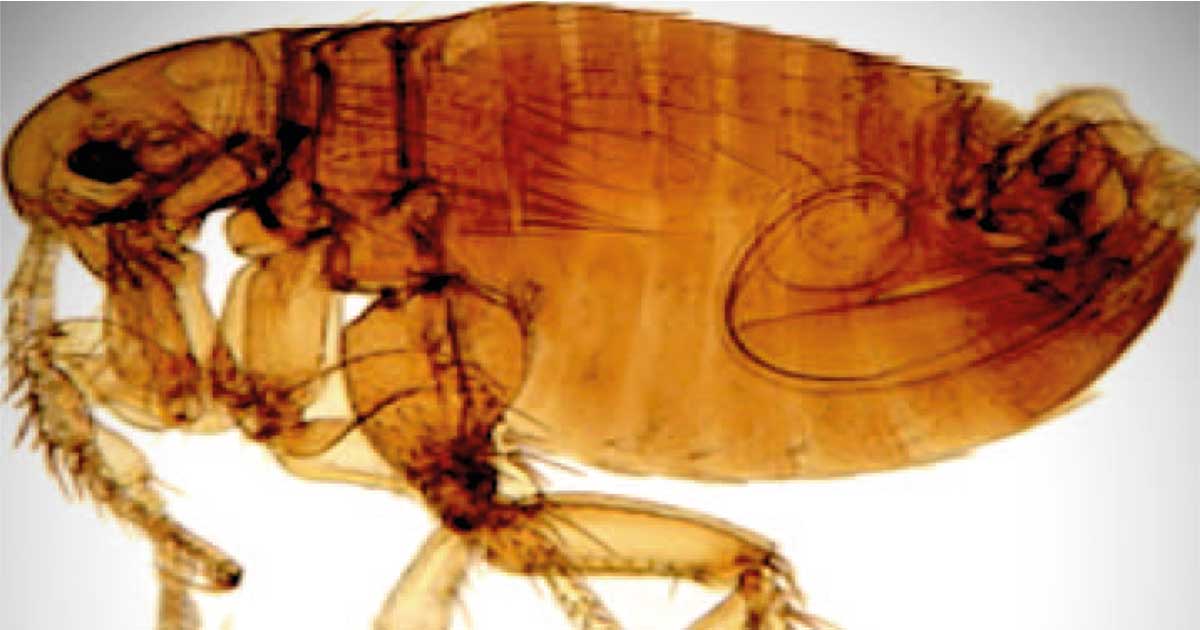

An adult male flea.

Our understanding of ectoparasites has evolved tremendously. The ectoparasiticide drug landscape and ectoparasite control are continually changing, and mirroring the evolving nature of ectoparasites.

As ectoparasiticides continue to push the boundaries, the veterinary profession needs to take a holistic approach to flea and tick control to ensure success. However, a big question the veterinary profession is still grappling with revolves around the frequency of treatment, the number of doses required to achieve better protection, and which animal should be targeted for treatment.

On one hand, treating pets only during high-risk seasons may not provide adequate coverage. On the other hand, year-round treatment carries an elevated risk of excessive treatment and potential for drug resistance development.

The technical aspects involved in the design of an optimal flea and tick control plan can be challenging on their own. However, poor owner compliance is another big challenge that can hinder the successful delivery of the parasite control plan – even at the best of times.

Partnership between clinicians, parasitologists and pharma can significantly facilitate knowledge development and knowledge transfer to end users.

Infestation of dogs and cats with fleas and ticks remains a real problem for many pet owners.

Fleas feed on blood – and a severe or prolonged infestation can kill a dog or cat. A multitude of fleas have the potential to cause anaemia so severe that a pet – especially a small puppy or kitten – could die without a blood transfusion.

Additionally, fleas can transmit potentially fatal diseases, such as feline infectious anaemia, and act as the intermediate host for the tapeworm of dogs and cats, Dipylidium caninum.

Fleas can also serve as the vector of some microbial agents that may affect humans, such as Bartonella henselae, the causative agent of cat scratch disease. Affected humans can exhibit flu-like symptoms, regional lymphadenopathy and potentially fatal complications in immunodeficient patients.

Like fleas, ticks can compromise the health of the affected animal through various mechanisms, such as:

- blood-feeding, which can lead to severe anaemia and immunosuppression

- development of pyogenic lesions caused by secondary bacterial infection around the site of a tick bite

Additionally, toxins secreted in the saliva of certain ticks can cause tick paralysis.

Importantly, ticks can transmit serious diseases to the pets, such as ehrlichiosis and babesiosis. The latter has already been found in dogs in Harlow, Essex (Phipps et al, 2016).

Ticks are also responsible for the spread of zoonotic diseases to humans, such as Lyme disease, human babesiosis, human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, tularaemia and rickettsial diseases.

One of the reasons is the fact fleas and ticks are highly dynamic organisms with a dynamic ecology, which can be influenced easily by many environmental and human-related factors.

Many classes of ectoparasiticides have been developed with various modes of action, speed of kill and spectrum of activity.

The recent introduction of isoxazolines to the ectoparasiticide market was a direct response of the increasing demands for developing new strategies for the control of ectoparasites that are most likely to impact the health and welfare of companion animals.

Therefore, it is not straightforward to establish an optimal preventive protocol of these pests, unlike for therapeutic management of other medical conditions.

Veterinarians should be aware that additionally to adequate ectoparasiticide coverage, other factors – including optimal dosing, interval of drug administration, and duration of therapy – are key factors influencing clinical outcomes.

Shifting parasite control to year-round protocol

The management of flea and tick infestations remains an important health issue in both veterinary and human medicine.

One difficulty in designing an optimal parasite control plan is the heterogeneity of the animal characteristics, and the lifestyle and circumstances of the pet owners.

Some professional bodies – such as the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites in Europe and the Companion Animal Parasite Council in the US – are embracing a shift from seasonal flea and tick control to a year-round control approach to cope better with the constant risk of flea and tick infestations.

The emerging trend is to support the shift away from ad hoc parasite control, which can be vulnerable to failures, to the all-year use of preventive ectoparasiticides to achieve better control and avoid any unnecessary suffering if the pet encountered an infestation.

What owners want

Many pet owners choose to not follow certain instructions – or adopt a certain parasite control model – due to financial and non-financial reasons, such as a belief year-round protection is not needed, or due to forgetfulness.

On the other hand, some veterinarians may not discuss parasite control plans with pet owners due to an inadequate level of knowledge in parasitology, limited time during consultations and/or an increasing dependence on broad-spectrum antiparasitics (Zajac et al, 2000).

Regardless of who is to blame, poor owner compliance is one of the most common reasons for ectoparasiticide treatment failure. Previous surveys – conducted at small animal hospitals in the US (Gates and Nolan, 2010) and Portugal (Matos et al, 2015) – have shown only a small proportion of dogs and cats had received year-round protection against the most common ectoparasites.

Promoting pet owner compliance with a certain flea and tick control plan extends beyond the mere prescription of the ectoparasiticide. To really improve owner compliance, awareness campaigns and educational programmes – alongside improving the vet-client relationship – are essential (Elsheikha, 2016).

Handling complaints

Veterinary practices that have efficient complaint management systems will have some advantages over more established practices.

Learning from mistakes can be very useful; therefore, it is important for businesses to have awareness of the reasons for non-satisfaction of their clients.

Also, it is important to continuously evaluate the satisfaction of pet owners and improve the delivery of the pet care service.

Smart businesses should convert challenges posed by unhappy pet owners into opportunities to improve the delivery of their service. This will definitely improve trust and establish long-term relationships with clients.

Partnerships to enhance flea and tick control

Understanding the science that supports the ectoparasiticide product is important.

The development of any new strategies should be based on the best science available, which builds on the experience of multiple investigators in the field. This strategy can facilitate streamlining existing research approaches to field studies and clinical trials, and will allow targeting of patients most likely to benefit from the treatment.

Lack of research investment is a prominent challenge that needs to be looked at by all stakeholders. Veterinarians and pet owners ask many questions no answers exist for – or, to be more precise, no answers exist that are backed up with solid scientific evidence.

It has been not easy to convince a drug company that some research ideas will result in crucial insights into the epidemiology and pathogenesis of a prevalent parasitic disease, or the efficacy of certain treatment protocols.

On the other hand, reliance only on private funding makes it difficult to conduct a large or independent study.

Establishing partnerships between veterinarians in practice, parasitologists with good experience, and pharmaceutical companies can tackle challenges in generating the right evidence needed to demonstrate the efficacy of one parasite control plan over another.

These partnerships are more likely to hit on novel ideas that are game changers in flea and tick control in small animal practices.

Outlook

When the author looks to the future of flea and tick control, he sees two main agents of change within the next 10 years – development and adoption of innovative control strategies, and the expansion of the ectoparasiticide portfolio.

The traditional parasite control plans, which use a one-size-fits-all approach, will need to adapt to the changing trends in parasite ecology and epidemiology. The implication here is that control plans will need to have the required flexibility to mirror the dynamic nature of flea and tick infestations.

More information is available in specialised reports about the risk of ticks and tick-borne diseases (Wall et al, 2017), and fleas and flea-borne infections (Bourne et al, 2018). Both reports are based on scientific and technical discussion meetings of experts on these timely issues.

Conflicts of interests

The author declares he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Bourne D, Craig M, Crittall J, Elsheikha H, Griffiths K, Keyte S, Merritt B, Richardson E, Stokes L, Whitfield V and Wilson A (2018). Fleas and flea-borne diseases: biology, control and compliance, Companion Animal 23(4): 204-211.

- Elsheikha H (2016) Flea and tick control: innovative approaches to owner compliance, Veterinary Times 46(10): 6-10.

- Gates MC and Nolan TJ (2010). Factors influencing heartworm, flea, and tick preventative use in patients presenting to a veterinary teaching hospital, Preventive Veterinary Medicine 93(2-3): 193-200.

- Phipps LP, Del Mar Fernandez De Marco M, Hernández-Triana LM, Johnson N, Swainsbury C, Medlock JM, Hansford K and Mitchell S (2016). Babesia canis detected in dogs and associated ticks from Essex, Veterinary Record 178(10): 243-244.

- Wall R, Pearson S, Tasker S, Hansford K, Bourne D, Cull B, Elsheikha H, Fitzgerald R, Phipps P and Stokes L (2017). Ticks and tick-borne diseases: a roundtable discussion, Companion Animal 22(4): 199-207.

- Zajac AM, Sangster NC and Geary TG (2000). Why veterinarians should care more about parasitology, Parasitology Today 16(12): 504-506.