30 Mar 2023

Gastric diseases in dogs: common condition cases

Ferran Valls Sanchez provides four comprehensive case studies, including diagnosis and treatment, for typical diseases in canine patients.

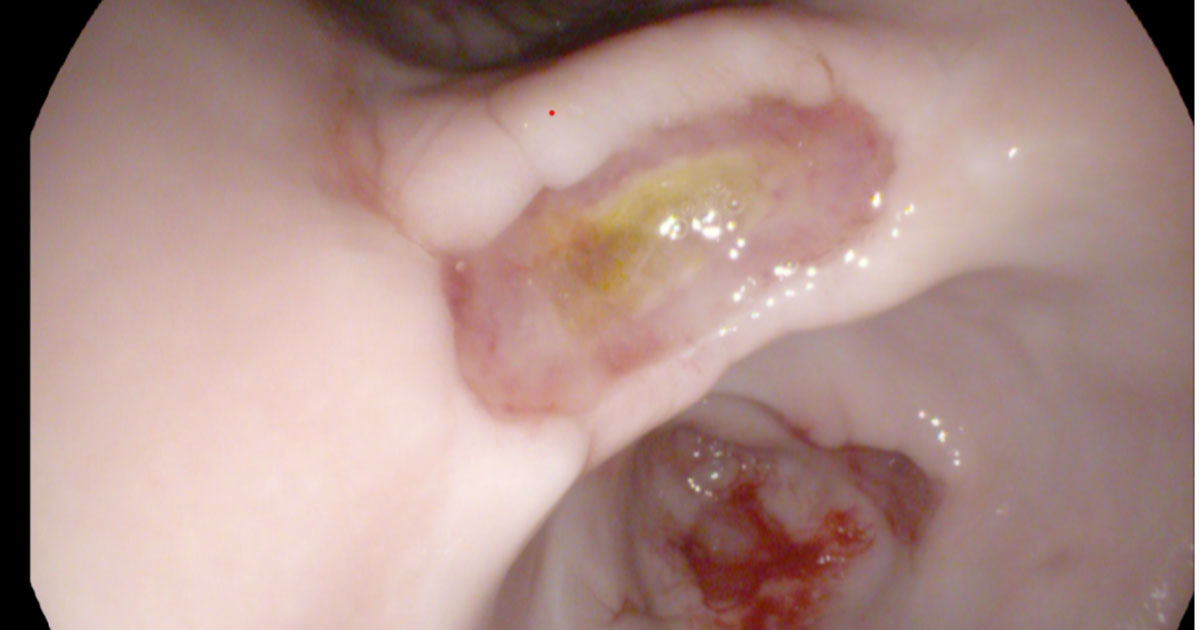

Figure 1. Ulcers in the one-year-old French bulldog.

In small animal medicine, some common gastric diseases are found. Among them, this article will focus on inflammatory bowel disease, gastric ulcers, neoplasia and gastric foreign bodies, using case examples followed by discussion and take-home messages.

Clinical signs associated with gastric disease vary depending on the severity and extension of the disease (for example, other parts of the GI tract), but common clinical complaints are vomiting and anorexia.

Equally, diagnostic approach needs to be tailored to each case, but abdominal ultrasound and gastroscopy (and biopsies) are fundamental in many cases.

Treatment and prognosis depend on the underlying cause:

- In some acute/mild cases, symptomatic treatment may be elected in the first instance, using GI diet and anti-nausea medications. However, if the dog is a “known scavenger”, abdominal radiography or abdominal ultrasound is recommended to rule out/in gastric foreign body. If, after a few days, a lack of response is noted (no improvement/deterioration), this should trigger the performance of haematology/biochemistry and abdominal imaging.

- In chronic vomiting, when the patient is stable without any other sign/finding, it is advisable to perform haematology/biochemistry to seek for any evidence pointing toward a specific disease (for example, electrolytes for Addison’s disease or hypercalcaemia, elevated liver enzymes, changes suggestive of iron-deficiency anaemia, and so forth), and if they are unremarkable, diet trial (with GI or hypoallergenic diet) can also be considered a first step.

A one-year-old female entire French bulldog presented due to chronic vomiting (eight weeks) and hyporexia. Physical exam revealed a poor body condition score (two out of nine) and pale mucous membranes.Haematology revealed a severe regenerative anaemia (haematocrit 0.15L/L, reference range 0.41L/L to 0.61L/L), with sub-population of microcytic hypochromic cells. Biochemistry was unremarkable. Abdominal ultrasound revealed pyloric thickening.

Gastroscopy revealed three large superficial ulcers (two pyloric antrum and one on the lesser curvature; Figure 1). Biopsies revealed inflammation. The dog received a blood transfusion of packed red blood cells, and was started on omeprazole (twice daily) and iron supplementation.

The patient showed a good improvement (medications were discontinued after two months). Repeated endoscopy or endoscopic capsule were discussed to confirm resolution of the ulcers, but declined.

Gastric ulcers can be due to different causes: gastric disorders (such as chronic inflammatory enteropathies, neoplasia or foreign bodies), and non-gastric disorders (pancreatitis, liver disease, renal disease or hypoadrenocorticism); however, despite extensive investigations, a cause is not found in many cases.

Abdominal ultrasound can be used for its diagnosis, but ulcers may be missed in 35% of cases (non-perforated). Gastroscopy allows confirmation of the problem – samples should not be taken from the middle of the ulcer as they may only show inflammation and necrosis, and also would increase the risk of perforation.

Endoscopic capsule can be used to locate an ulcer, but does not allow sampling. Finally, the absence of macroscopic blood (haematochesia or melaena) does not rule out GI bleeding.

Take-home messages

- Absence of haematochesia/melaena does not preclude GI bleeding.

- Biopsies should be taken from the edges of the ulcer.

- In many cases of gastric ulceration, a definitive cause is not found.

A nine-year-old male neutered Labrador retriever presented due to chronic vomiting (four weeks, progressive in frequency). On physical exam, the dog was depressed, but the rest was unremarkable.

Haematology and biochemistry were done to screen for possible extra GI causes, and also assess albumin.

Mild anaemia (haematocrit 0.35L/L; reference range 0.41L/L to 0.61L/L), with low reticulocyte haemoglobins was reported, which could suggest iron-deficiency anaemia (GI bleeding).

Biochemistry was unremarkable. Basal cortisol was low, but an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test ruled out Addison’s disease, as post-ACTH cortisol was considerably increased.

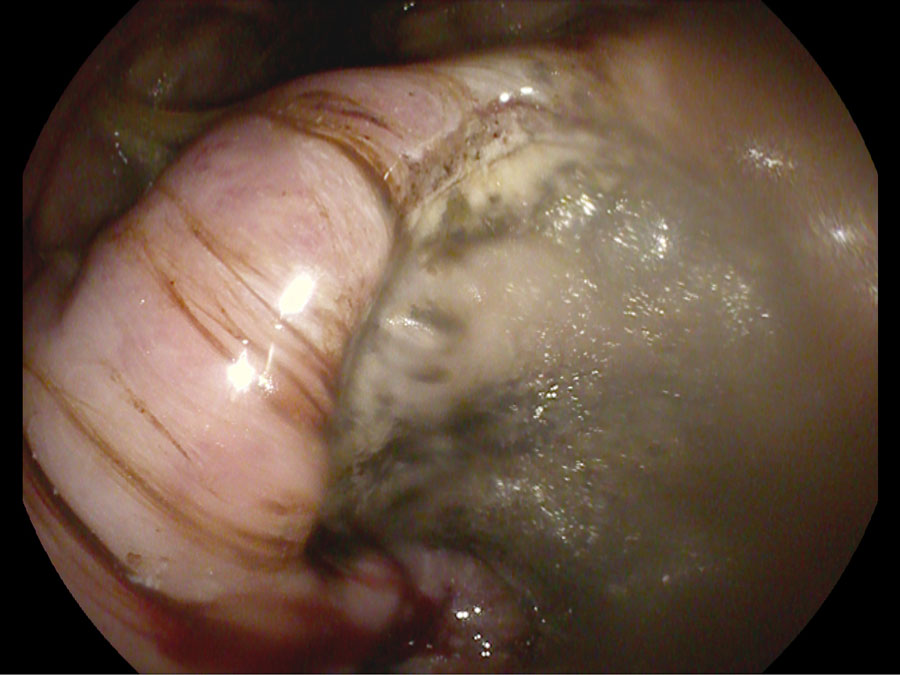

Ultrasound revealed a diffuse thickening of the gastric wall. Fine-needle aspirates were attempted, but the sample was non-diagnostic. Gastroscopy was performed, which revealed a very severe thickening of the lesser curvature, causing a stenotic effect on the pyloric antrum.

A very large, moderately deep ulcer was revealed on the thickening of the lesser curvature (Figure 2). Biopsies were taken and revealed gastric carcinoma.

The dog was discharged while waiting results on omeprazole and maropitant, but was euthanised a few days later due to deterioration.

Gastric cancer is rare and the most common form is gastric carcinoma. Some breeds are more affected, such as the Tervueren, bouvier des Flandres, Groenendael, collie or standard poodle. It usually affects middle aged and older dogs, and males.

Gastric cancer usually arises from lesser curvature or pylorus. Cytology through fine-needle aspirates can provide a diagnosis, but endoscopic biopsies are usually more effective. Prognosis is poor, even after surgery.

Other tumour types, such as mesenchymal neoplasia, can also occur (leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas), which usually arise from cardias and fundus. Some response has been seen to tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Take-home messages

- Gastric carcinoma is the most common type in dogs and prognosis is poor.

- Usually, gastric carcinoma originates from the lesser curvature or pyloric antrum.

- Prognosis is poor.

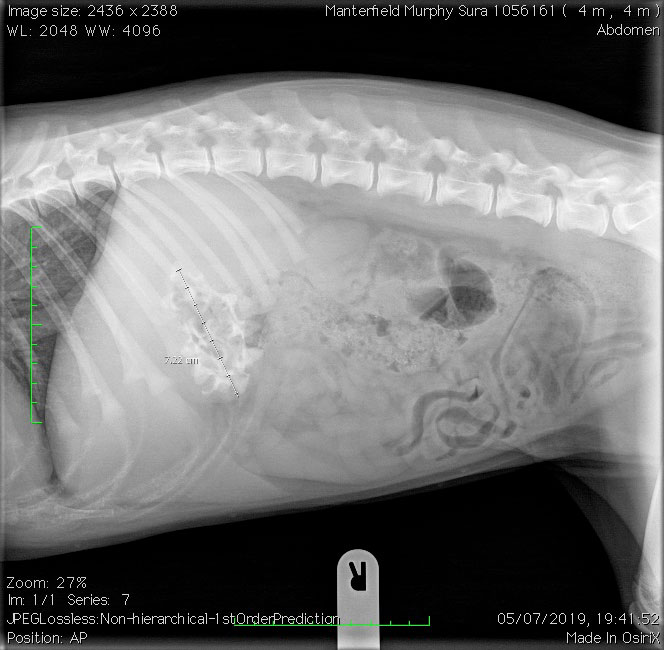

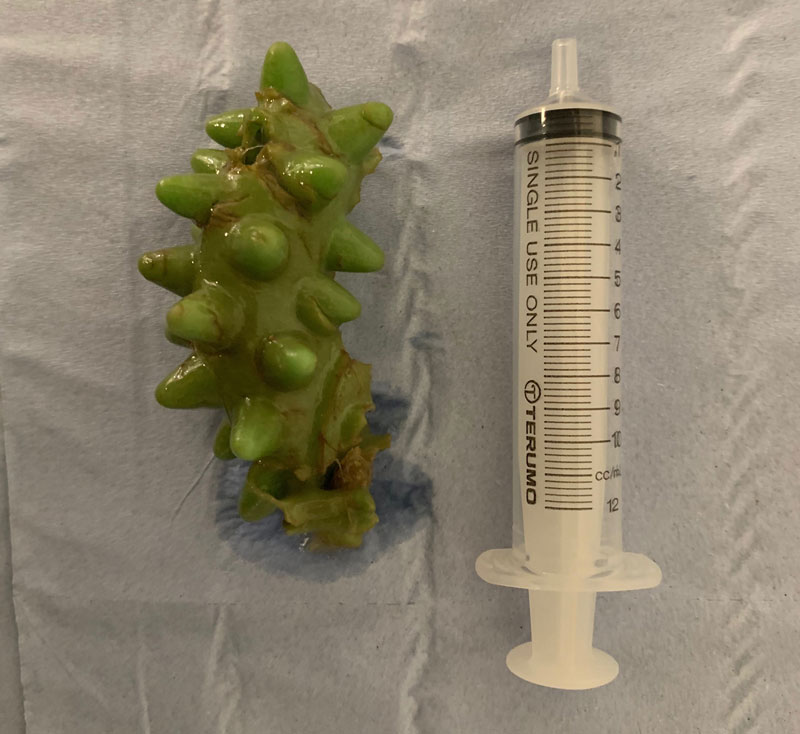

An 11-old-year female spayed beagle presented due to suspected ingestion of a wooden comb. The dog had undergone three previous surgeries due to intestinal foreign bodies.

Due to the type of material of the suspected ingested foreign body, abdominal ultrasound was performed, which revealed a shadowing structure. Endoscopy was performed and a few wooden fragments were removed, along with a sock that was already entering the duodenum. The dog showed a very good recovery.

Signalment (puppies) and history (to know if dog is a known scavenger, previous surgeries) are fundamental to order “foreign body” in your differential diagnosis list. Sometimes it is easier, as the owner has witnessed the ingestion, but not in most cases.

Abdominal radiography/ultrasound is recommended to confirm the problem and locate the foreign body, as location will affect the possible treatment (endoscopy versus surgery).

Treatment will be decided depending on the type of foreign body, size, location and time of ingestion. Endoscopic removal is less invasive and should be used as first option when possible (if you are not sure whether it is a feasible option, contact a medicine specialist for discussion). Sometimes, emesis can also be considered.

Finally, a combined approach between surgery and endoscopy/big forceps can be done (Figures 3 to 5).

With “repeat offenders”, investigations for underlying GI disease (that can lead to pica) or behavioural treatment may be considered.

Take-home messages

Location and size of the foreign body will affect treatment options.

- Endoscopic removal should be considered whenever possible.

- Repeat offenders should undergo investigations for an underlying cause or behavioural training.

A one-year-old male entire Labrador retriever presented due to four weeks of vomiting.

Haematology was unremarkable and biochemistry showed mild increase in alanine transaminase (109IU/L; reference range 11IU/L to 81IU/L). Basal cortisol ruled out Addison’s disease. Cobalamin was low. Abdominal ultrasound revealed thickening of the gastric wall. Endoscopic biopsies were taken, which revealed lymphoplasmacytic inflammation.

The dog did well on a hypoallergenic diet, maropitant and oral cobalamin supplementation.

Chronic inflammatory enteropathies (CIE) are a common cause of chronic GI signs in dogs and affect the stomach (usually, along with the intestines), and include food responsive/antibiotic and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Diagnosis is only reached in a definitive way through histopathology, but you can get a presumptive diagnosis assessing response to treatment trials (for example, diet or immunosuppressants) and excluding structural disease with imaging.

It is recommended to perform imaging before starting immunosuppressants.

The main benefit of performing endoscopy and biopsies is to rule out, as much as possible, malignancies – in particular, lymphoma – as a subset of cases can have completely normal ultrasound appearance.

Food-responsive enteropathy usually affects younger animals, whereas IBD affects older animals. Antibiotic responsive disease is uncommon. Food-responsive enteropathy and IBD can have same histological findings, and diagnosis is based on response to treatment.

As aforementioned, treatment is based on diet/antibiotic and/or immunosuppressants.

Owners should be instructed to complete the diet trial appropriately (no other food and to avoid scavenging), and response is usually seen within two weeks.

Prednisolone is usually the first option among immunosuppressants. Ongoing research is also underway about faecal microbiota transplants, its impact on the receptor microbiome and clinical progress in these cases.

Cobalamin level may be low and should be checked in cases with chronic GI signs, as it may require supplementation.

Injectable protocols exist, but oral protocol has also been proven to be effective in cases of enteropathy.

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency can also cause cobalamin deficiency, so trypsin-like immunoreactivity evaluation should be considered.

For further information about cobalamin, the author recommends referring to the Gastrointestinal Laboratory from Texas A&M University.

In the majority of cases, the prognosis is good, but the owner needs to understand that mild/intermittent or flare up may remain. When the condition is causing protein-losing enteropathy, the prognosis is more guarded.

Take home messages

- CIEs are a common cause of chronic GI signs in dogs.

- Mild elevation of liver enzymes can occur with GI disease.

- Performance of imaging and biopsies should be discussed with the owner before starting immunosuppressants.

- Treatment trial can also work as diagnostic tool.

- Cobalamin levels should be checked in dogs with chronic GI signs and may require supplementation.

- Use of some of the drugs mentioned in this article is under the cascade.

References

- Fitzgerald E et al (2017). Clinical findings and results of diagnostic imaging in 82 dogs with gastrointestinal ulceration, J Small Anim Pract 58(4): 211-218.

- Liptak JM (2020). 23 – Cancer of the gastrointestinal tract. In Vail DM et al (eds), Withrow & McEwen’s Small Animal Clinical Oncology (6th edn), Elsevier, St Louis: 432-491.

- Texas A&M University School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. Cobalamin information.