25 Feb 2025

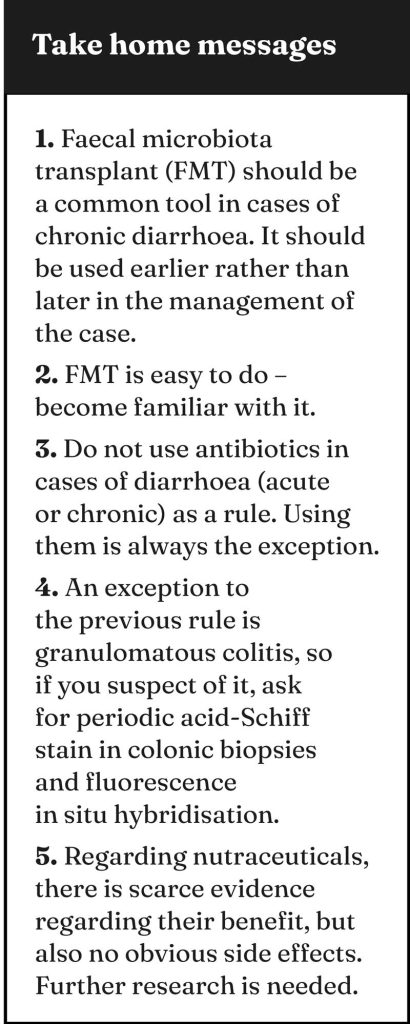

Ferran Valls Sanchez DVM, DipECVIM-CA(Int Med), MRCVS provides insights into the roles of microbiota, antibiotics, probiotics and more on key conditions in canines, as well as the diagnostic tools available to practitioners.

Image: © Life in Pixels / Adobe Stock

Vomiting and diarrhoea often appear in our diaries, making gastrointestinal disorders one of the most common reasons for consultation in veterinary medicine, alongside dermatopathies.

As a result, staying current with advances in this area is essential for any small animal practitioner.

But what is new in the field of gastrointestinal health? Two key subjects have emerged in recent years:

This article will mainly focus on these two areas, offering insights into the latest research. Then, we will follow with the importance of insisting with diet trials and an updated classification for chronic inflammatory enteropathies (CIE).

We will finish with some diagnostic tool insights that can aid the practitioner in addressing gastrointestinal problems effectively.

The increasing buzz around microbiota is far from unwarranted. As research into this field evolves, the compelling evidence to support the role of microbiota in the health and disease of dogs and cats rises as we speak.

Gastrointestinal microbiota (“micro” – small, “bios” – life) is defined as the collection of live microorganisms (bacterial, fungi, protozoa and so forth) that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract and produce (directly or indirectly) multiple products with different effects.

The role played by the microbiota is yet to be completely understood; however, multiple functions have been attributed to it in healthy animals. Supporting the immune system, composing the intestinal barrier (competing with pathogens for oxygen, nutrients, adhesion sites and so forth), producing immune-modulatory substances and providing nutrients are only a few of many activities. Similarly, there is mounting research on the effect of the microbiota in the pathophysiology of multiple diseases. Alteration of the diet, acid production, intestinal motility or architecture can impact the microbiota composition and, consequently, the physiology of the gastrointestinal tract.

The alteration of the microbiota is also referred to as dysbiosis, and it can be measured as an index. The higher the dysbiosis index (DI), the greater the disruption of helpful microbiota present. DI is currently available in some laboratories. The susceptibility of the individual is also important, as not all cases of dysbiosis result in evident clinical signs.

Multiple therapeutic tools target the microbiota. Faecal microbiota transplant (FMT) is one of them and involves transferring faeces from a healthy donor to a diseased individual with the goal of modifying the receptor gut microbiota, leading to a clinical benefit.

In the past few years, there has been important research published about the use of FMTs, but let’s start with a case I saw recently in consult.

Pablo was a five-year-old, male, entire French bulldog with a diagnosis of parvovirosis. Pablo was receiving supportive treatment, and we believed he had turned the corner, but was having ongoing diarrhoea.

We explained to the carer the possibility of performing a faecal microbiota transplant, and the carer themselves brought stools from a friend’s dog, which became the donor.

Pereira et al described a quick resolution of the diarrhoea and a shorter hospitalisation time in dogs with parvovirus receiving FMT (n=33, and 33 control)1.

The number of deaths also decreased in the group receiving FMT, but the difference was not significant. These positive results were also confirmed by a more recent study by Kalita et al in 20242.

Leo was a two-year-old, male, neutered cross-breed with chronic diarrhoea for which a couple of diets had not worked to resolve the signs. We discussed with the carer to keep trying with the diet, but also to consider FMT before jumping into using prednisolone, as Leo was very young and perhaps we could manage the signs without drugs.

In 2023, Toresson et al investigated the addition of FMT as a complementary therapy for dogs with chronic enteropathies already undergoing diet and drug treatments (n=41)3. In most cases, improvements were observed in the clinical index, faecal quality and/or activity levels3.

Notably, the DI was higher in the non-responder groups, suggesting that this parameter could have prognostic value3. This may prove useful in guiding treatment decision-making and managing pet owners’ expectations.

In contrast, a 2022 study by Collier et al did not report a clinical difference between two groups of dogs with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; n=13), one receiving FMT or not on top of corticosteroids and diet management4. However, based on my clinical experience, and insights gained from attending forums and joining discussions, I believe FMT may be more effective when used as an adjunct to diet therapy or after attempting dietary trials.

Another reason for potential “FMT disappointment” is related to how it has generally been used in clinical practice. Until a few years ago, I used FMT primarily as a last resort in cases of severely ill patients with protein-losing enteropathy, where previous treatments have failed. Therefore, in the few cases I had tried it, it did not yield positive results, likely due to a biased patient selection.

In my opinion, FMT should be considered much earlier in the treatment process if we want to start expecting better outcomes.

A fuss and a mess? No. FMT is one of these things that seems so tricky to carry out that many people avoid giving it a go. However, once you do start it and set a system in place (possible donors, screening tests, deciding who assumes these costs, how and where to store the product, and so forth), the rest is easy.

To ease the integration of FMT and consolidate its widespread use, comprehensive and user-friendly guidelines were published in late 20245. They cover every step of the process, from selecting a suitable faecal donor to the administration of the transplant itself.

On a final note, it’s important to address the potential downsides as well – after all, acknowledging possible adverse events makes us humans trust it more. While the available data is sparse and mainly extrapolated from human medicine, FMTs are considered generally safe5. Most of the reported adverse effects are deemed mild, such as worsening of the diarrhoea, constipation, nausea, vomiting or dysorexia.

A 2018 review reported that 10 out of 140 cases experienced severe adverse events, including aspiration pneumonia, perforation and sepsis5. However, it was challenging to conclude that these events were due to the FMT and not because of the underlying condition.

From a non-medical point of view, obviously the difficulty of FMT is to be aware of it, get familiarised and as “ready” as possible, otherwise it’s an easy option to reject.

I ran an informal survey with friends and colleagues about FMT, which resulted in the following: six had already used FMT in management of chronic inflammatory enteropathy and 18 had not. All six people that had used it were working in referrals. FMT should not be a “referral thing”; it should become a first opinion tool.

It’s becoming more and more difficult to find a justification for the use of antibiotics in cases of gastrointestinal disease of dogs and cats.

Unfortunately, in my experience, it’s still common to find many inpatients and outpatients suffering from diarrhoea that are prescribed antibiotics. In the past few months, I have “crossed out” innumerable times antibiotics from hospitalisation sheets of dogs being treated with gastrointestinal disease.

The belief on an unproven causal relationship between the use of these drugs and a clinical improvement is still very weak in small animal practice. It’s also difficult to accept that, sometimes, “time” and/or “diet” and/or “fluid therapy” is enough, as many practitioners and pet carers feel uneasy about “not giving anything” when antibiotics are not included in the supportive treatment plan.

However, very recent and interesting research was published in December 2024 in Denmark about expectation from dog’s carers about antibiotic usage6. This study evaluated how many carers expected antibiotic to be dispensed for acute diarrhoea and how they felt if they were not prescribed. Only 6 out of 90 of carers expected antibiotic prescription and only 2 out of 90 expressed dissatisfaction about not receiving this prescription6.

So, perhaps our main enemy may be ourselves. It’s uncomfortable “not doing anything”, but after doing “nothing” a few times, it gets easier and one realises about the benefits of this approach.

Another difficulty when trying to decrease the use of antibiotics is that the impact of the overuse of antibiotics is rather intangible, the consequences are not immediate, and it’s more about population medicine and the future.

It’s like rodents and the new generations of rodenticides; the negative impact occurs so much further down the line that no association is made.

Although further research is needed, it is well established that antibiotics can alter the composition of the gut microbiota, which in turn predisposes individuals to the development of disease.

With regards to its clinical applications, the evidence is clear.

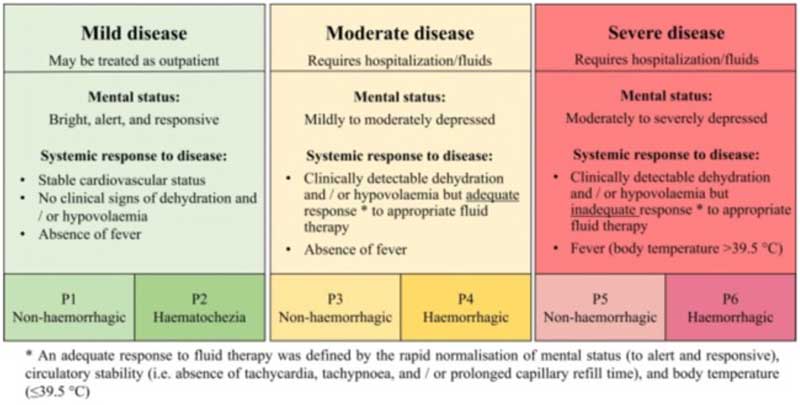

Acute diarrhoea: a systematic review and meta analysis, conducted last year to optimise the antimicrobial guidelines by the European Network for Veterinary Optimization of Antimicrobial Therapy, concluded that the use of antibiotics does not reduce the duration diarrhoea in mild and moderate cases7. But what exactly defines “mild” and “moderate” cases? The panel conducting the review classified cases based on factors such as mental status, dehydration and cardiovascular status, response (or lack thereof) to fluid therapy, presence of fever, and whether blood was present in the stools. No definitive conclusions could be made about severe cases, as most cases had received antibiotics, and no proper comparison of outcomes of groups with and without antibiotics were available for review7 (Figure 1). A previous study using target trial emulation (a technique used more and more in human epidemiology) also concluded the same8.

Chronic diarrhoea: a 2020 proposal for the rational use of antibiotics in dogs with chronic diarrhoea recommended antibiotic therapy only after all other potential causes have been ruled out9. This includes confirming the absence of inflammation through histopathology (or receiving inconclusive results) and providing evidence for a primary bacterial infection. If biopsies are not performed, and only if signs don’t respond to other treatment trials, such as diet, corticosteroids and so forth, should antibiotics then be considered. Other possible indications would be the presence of fever or left shift neutrophilia/leukopenia along with a known bacterial agent.

As you can see, the presence of blood is not an indication for antibiotic use.

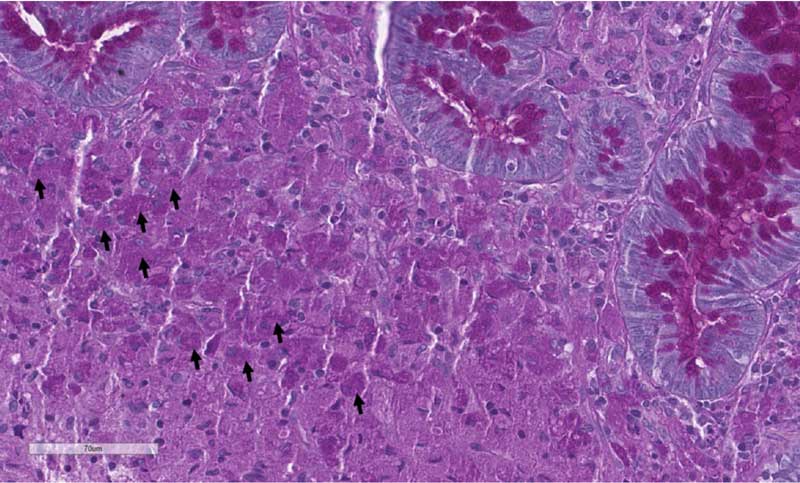

One notable exception is granulomatous or histiocytic ulcerative colitis, a condition more commonly seen in breeds such as the boxers or French bulldog, and often linked to Escherichia coli infection (Figure 2). It’s really important to be aware about this differential diagnosis, as it would be easy to misdiagnose these cases for IBD and treat them with immunosuppressants without success.

In these cases, if histopathology and additional tests (such as periodic acid-Schiff [PAS] stain or fluorescence in situ hybridisation [FISH]) confirm the diagnosis, antibiotic therapy can be warranted.

Typically, a quinolone is chosen, though some experts recommend culturing a colonic biopsy, as resistance to quinolones has been documented. I started submitting samples for bacterial culture and susceptibility testing a few years ago to ensure appropriate treatment.

Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics are also called nutraceuticals, and you can read their definitions in Panel 1.

The two previously mentioned large studies did not show a clinically relevant effect of probiotics and synbiotics on duration of the diarrhoea in dogs with acute signs either7,8. A small, favourable effect of a prebiotic was detected in one of the reviewed studies, with low level of certainty. It is also true that no side effects were concluded.

In contrast, a recent study evaluated in dogs with acute (n=8) and chronic diarrhoea (n=29) showed a favourable clinical response in 7 out of 9 and 18 out of 29 of dogs, respectively, receiving probiotics. Seven dogs exclusively received the probiotic as a treatment and four out of seven showed a complete resolution of the clinical signs10.

Further research is needed, including studies with control groups, to draw more definitive conclusions. The extensive range of products also makes research more challenging. However, better a probiotic than an antibiotic for sure.

Life is often about expectations; diet trials don’t skip this rule. It’s very important to explain the carers that:

We can attempt with hydrolysed, novel proteins, gastrointestinal diets and so forth; what I have learned is that it’s more about finding the right diet for the specific dog than about a specific type of diet.

Marketing, social media and word of mouth have an impact on carers, and often they come up with a new diet that I haven’t heard before. I always like to be very involved on selecting the diet, as every day there are more and more diets available. It’s important to check the ingredients of the different diets and gather as much information as possible about them. If research is available, even better, but it’s not often the case. This does not mean that it is not good or effective.

Because of this, I try to build my own “evidence”, so know that “Bobby was on DeliciousFoodforCuteSnouts and it worked well”. To assess outcomes is the only way to improve, keeping in mind, however, that each case is different.

In some cases where the dog is very fussy, palatability is becoming an issue or, with comorbidities, it may be very useful to refer to a board-certified nutritionist for a homemade diet formulation or advice about the commercial pick. However, it’s important to explain to the carer about the pros and cons of homemade diets. They are a good option to increase palatability, to try to tailor to the preferences of the dog, and also these diets may provide more variety than commercial diets.

On the other hand, long term, the cost may be a tiny bit higher than many commercial options and require getting the ingredients and cooking them, which equal to “time”. Some of these diets can be frozen and cooked in batches, making them more practical.

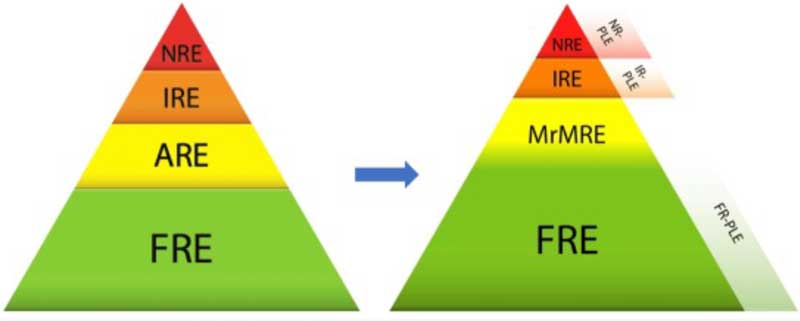

CIEs are a very common cause for chronic gastrointestinal signs. Up until recently, the most common classification was:

However, lately, and keeping in mind all we have discussed, an updated classification for CIE has been suggested11. Recent research showed that cases initially classified as non-responsive enteropathies responded to diet trials. It is proven that diet has also an impact on the gut microbiota.

Also, we have moved on from ARE to microbiota-related modulation responsive enteropathy (MrMRE), which encompasses all the enteropathies responsive to different microbiota modulation therapies, such as probiotics and FMT.

There is an overlap between FRE and MrMRE, as in the former there is also a role for the microbiota. The growth of FRE cases and the appearance of MrMRE has caused the cases of IBD to get smaller. We can see the impact of these changes in the graphic in Figure 3.

Basal cortisol. Hypoadrenocorticism is an uncommon cause of gastrointestinal signs in dogs. In a study by Tardo et al, only 1 out of 112 dogs with normal potassium and chronic gastrointestinal signs had hypoadrenocorticism12. Similarly, in a previous study involving dogs with chronic gastrointestinal signs, 28 cases had low resting cortisol concentrations, but only 1 out of 282 had hypoadrenocorticism13. Interestingly, when basal cortisol levels were rechecked in the 28 cases, only 8 had persistently low cortisol levels. Repeating basal cortisol measurements can be a useful alternative to rule out hypoadrenocorticism – particularly when suspicion is low or when adrenocorticotropic hormone testing is unavailable or costly13. In summary, hypoadrenocorticism is an unlikely cause of chronic gastrointestinal signs in dogs. Keep this in mind when making clinical decisions – especially if there are financial constraints.

PAS stain. This is the name of the stain you need to ask to be run on colonic biopsies when you suspect granulomatous colitis. This stain points out the presence of glycoprotein from the bacterial wall inside macrophages – these macrophages are considered “PAS-positive” macrophages. The other useful test would be FISH, which proves the presence of E coli in the colonic mucosa, as well.

Polymerase chain reaction parvovirus in stools. A negative point of care (POC) test does not rule out parvovirus. If clinical signs suggest parvovirus infection, it’s important to submit a faecal sample for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing; for example, just one week before writing this article, I encountered a puppy with a typical parvovirus presentation – unvaccinated, gastrointestinal signs, and neutropenia – yet the POC test was negative. However, PCR testing of the stool confirmed the diagnosis. Correctly diagnosing parvovirus is crucial not only for treatment, but also for determining isolation protocols, preventive measures, and the overall management of the disease. False negatives with all diagnostic tests can occur due to several factors, such as reduced viral load in the faeces by the time that clinical signs appear. PCR is less affected by this issue. In summary, believe in your suspicions.

Helicobacter species. This often appears in gastric biopsy reports – what do we do with it? I’m also “annoyed” when it appears, as we don’t really know what to do with it. In human medicine, there is evidence about its association with gastritis and gastric cancer; however, this is not the case in veterinary medicine. Triple treatment (amoxicillin, metronidazole and omeprazole) should be considered if other therapies for other differential diagnoses have failed, and gastric inflammation and Helicobacter species have been identified. Basically, I only treat if the patient does not seem to respond to any other trial, and before considering immunosuppressants.

Folate. Labs often offer cobalamin and folate testing as a bundled package. However, given the current evidence and the fact that many cobalamin supplements already contain folate, there is not much point in measuring it. The clinical benefit of folate supplementation also remains unclear in veterinary medicine. Additionally, the outdated assumption that “high folate means small intestinal bacterial overgrowth” has been largely dismissed. Keep this in mind if evaluating cobalamin alone is a more economical option. Your clients will thank you and your approach won’t be affected at all.

Endoscopy. For any diagnostic test or treatment, we should balance clinical benefit/risks and costs. Regarding gastrointestinal disease, endoscopy to obtain gastrointestinal biopsies is the gold standard for the diagnosis of inflammation, and it’s as much as we can do to exclude neoplasia (without surgery); however, my clinical impression is that in dogs with chronic diarrhoea, where the ultrasound is not suggestive of neoplasia, endoscopy is unlikely to change the therapeutic approach. Some argue that this is obvious, but it’s important to communicate the likelihood of a test to have an impact on a specific case, even more if there are financial constraints or higher anaesthetic risk. An unpublished study (awaiting publication at the time of writing this article) by Jolly Frahija and others (including the author) concluded that in a population of dogs with chronic diarrhoea, and no ultrasonographic findings suggestive of neoplasia, the percentage of cases with neoplasia was low (3 out of 115). It is important to share this information to carers for them to make an informed decision about pursuing endoscopy.