21 Feb 2022

Heart of the matter – canine cardiovascular diseases

Emma Gerrard outlines the conditions to be aware of, and the vet nurse’s role in patient management.

Image © WavebreakmediaMicro / Adobe Stock

Heart disease is commonly encountered in veterinary practice and can account for approximately 15% of all medical cases seen within general veterinary practice (Stafford, 2008). It can affect patients of all ages and sizes, and certain breeds are more predisposed to disease than others.

Veterinary nurses’ role in the management of heart disease is diverse, and they are in ideal position to provide client support to ensure optimal cardiac patient care.

This article aims to provide an overview on the anatomy of the heart, the main structural diseases of the heart and a VN’s role in the management of a cardiac patient.

The heart is a muscular pump divided into four chambers – two atria and two ventricles – that lie within the mediastinum in the thoracic cavity. The interventricular septum completely separates the two sides of the heart, and unless there is a septal defect, the two sides of the heart never directly communicate.

Deoxygenated blood returns to the right side of the heart via the venous circulation. It is pumped into the right ventricle and then to the lungs where carbon dioxide is released and oxygen is absorbed. The oxygenated blood then travels back to the left side of the heart into the left atrium, then into the left ventricle from where it is pumped into the aorta and arterial circulation.

The pressure created in the arteries by the contraction of the left ventricle is the systolic blood pressure. Once the left ventricle has fully contracted, it begins to relax and refill with blood from the left atrium. The pressure in the arteries falls while the ventricle refills. This is the diastolic blood pressure.

What is heart disease?

Heart disease is a broad term used to describe a range of diseases that affect the heart. It can be a condition of the heart, blood vessels or valves that disrupts the normal function of the heart. Heart disease may be congenital (present at birth) or acquired (occurs in adulthood). Many heart diseases are heritable and can lead to heart failure.

Heart murmurs

Heart murmurs are created as a result of vibration of the structures within the heart, set in motion by abnormal, turbulent blood flow. Normally during chest auscultation, only two heart sounds are present, which are often described as “lub” and “dub”. When a murmur is present, an abnormal, extra sound is presented between the “lub” and “dub”, which makes a “shooshing” or “whooshing” noise.

Murmurs can be divided into three categories: innocent, congenital and acquired.

Innocent murmurs are commonly detected in young animals with no evidence of structural heart disease. These murmurs are quiet and soft, can be intermittent, and generally disappear between 12 and 15 weeks of age. This type of murmur can also be associated with excitement, fever and, in some cases, anaemia.

Congenital murmurs are often picked up at first vaccination, but can go undetected until later health checks.

An acquired heart murmur is one an animal develops during its life. These are often associated with heart valve defects or myocardial disease. Acquired murmurs can be a marker of significant cardiac disease, but some dogs can develop a murmur that has no detrimental effect.

The intensity or loudness of a murmur can be graded from one to six, with one the quietest and six the loudest. The intensity of a murmur does not always equate to the severity of the condition; however, a study by Caivano et al (2018) found that the loudness of heart murmurs associated with congenital abnormalities tended to be proportionate to the severity of the underlying condition. A similar study by Ljungvall et al (2014) confirmed the association between heart murmur intensity and degree of cardiac remodelling in mitral valve disease in dogs. Therefore, the presence of a moderate to loud murmur should always prompt additional investigations, such as echocardiographic examination.

Congenital heart disease

Congenital heart disease accounts for about 5% of the cases of heart disease seen in practice (Buchanan, 1992).

Congenital heart diseases are often detected at first vaccination when auscultation of the heart reveals a murmur. Auscultation is invaluable for detecting congenital heart disease in puppies. The sensitivity of this test depends on clinical ability and experience, but the specificity is relatively low due to the fact many heart murmurs are not associated with a significant cardiac disease (flow or “innocent” murmurs; Ferasin, 2020).

Owners may notice that their pet fails to grow, displays exercise intolerance, develops a cough, becomes dyspnoeic or has episodes of syncope. Canine congenital defects often have breed predispositions, and the most common defects include:

- aortic stenosis (AS)

- pulmonic stenosis (PS)

Other defects include cardiac shunts, which are abnormal communications between chambers of the left and right sides of the heart. These include:

- atrial septal defect (ASD; between the left and right atria)

- patent ductus arteriosus (PDA; between the aorta and pulmonary trunk)

- ventricular septal defects (VSD; between the left and right ventricles)

Aortic stenosis and pulmonic stenosis

A stenosis is a narrowing over a valve or an inadequate opening of the valves. PS and AS are equally prevalent congenital heart defects in which a malformation impedes the flow of blood through the heart.

AS is the most common congenital defect seen in dogs; boxers are thought to make up 50% of the number of dogs diagnosed in the UK (Martin and Corcoran, 1997). Other breeds commonly affected are Newfoundlands, German shepherds, golden retrievers, Samoyeds and Rottweilers.

Three types of AS exist, with the most common being subvalvular fibrous ring, followed by valvular and supravalvular (rare).

Subvalvular stenosis is also known as subaortic stenosis. AS is most commonly a narrowing or reduction just above or below the aortic valve, and very rarely affects the actual valve. This causes a partial obstruction of the blood flowing from the left ventricle through the aortic valves and into the aorta.

Patent ductus arteriosus

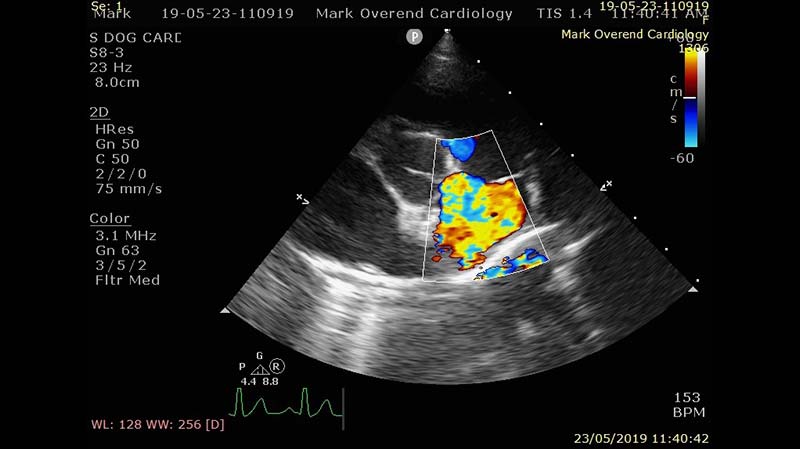

PDA is one of the most common congenital cardiovascular abnormalities seen in dogs. This defect usually leads to left-sided cardiac chamber dilation, arrhythmias, left-sided congestive heart failure (CHF), and, ultimately, death. However, it is also one of the few cardiac conditions that can be cured in small animal practice (Figure 1).

- arrhythmias

- dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

- myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD)

- pericardial disease

- vascular disease

DCM

DCM is one of the most commonly acquired canine heart diseases, and is more commonly seen in middle-aged male dogs (Tidholm et al, 2001).

DCM is a disease affecting the myocardium. The ventricles lose their ability to contract normally and the affected myocardium is unable to generate the pressures required to maintain cardiac output.

DCM most commonly affects the left side of the heart, specifically the left ventricle. As a result, blood backs up, causing pulmonary oedema (left-sided CHF). Less commonly, DCM can affect the right side of the heart, resulting in ascites and pleural effusion (right-sided CHF). In some dogs, both sides of the heart may be affected, with an obvious detrimental effect.

It tends to occur in giant breeds such as Newfoundlands, Dobermann pinschers, boxers and great Danes. DCM was previously seen in cats with taurine deficiency, although with the increase in complete commercial diets it is now rarely seen.

Clinical signs include weight loss, lethargy, exercise intolerance, breathlessness, coughing, ascites and heart murmur, and the signs are often apparently acute in onset.

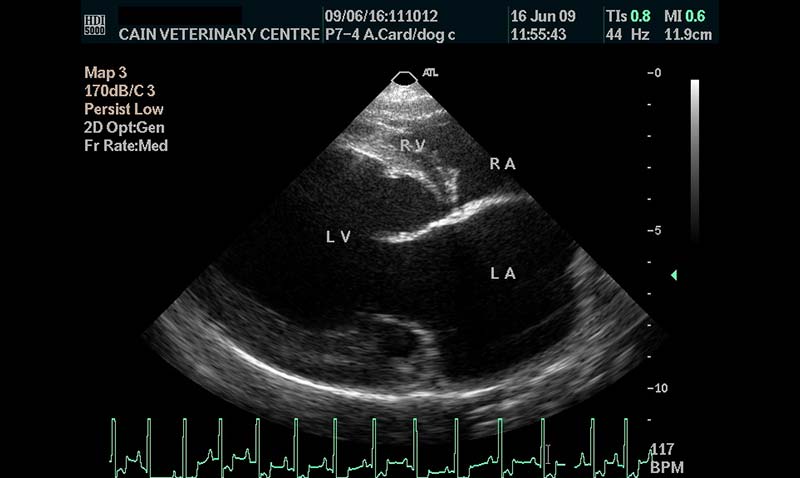

Many dogs with DCM have electrical changes, with atrial fibrillation a common rhythm disturbance, and sudden death can occur (Summers, 2002). Reduced cardiac output and poor ventricular contractility results in a weak pulse, tachycardia and poor peripheral perfusion in these patients. Diagnosis includes thoracic radiography (lateral and DV views), echocardiography and ECG.

DCM is a progressive, irreversible and terminal illness, and life expectancy depends on the patient and the severity of the heart damage. With effective and supportive treatment, along with regular checks, patients can have a good quality of life. Treatment depends on the severity of the disease and clinical signs, but often involves the use of ACE inhibitors and inodilators such as pimobendan, digoxin, furosemide and other anti-arrhythmics, depending on the case (Figure 2).

MMVD

MMVD is the most common cardiac condition in dogs and represents approximately 75% of all cases of cardiac disease seen in them (Linney and Neves, 2020). It is an acquired chronic degeneration of the heart valves causing valve malfunction.

Heart valves allow blood to move one way between the atria and ventricles, and they create a seal between the chambers to prevent regurgitation. When degeneration occurs, the valves have impaired closure, resulting in regurgitation. This causes volume overload in the heart chambers and vessels. The mitral valve is most commonly affected and this is often known as MMVD, which can lead to left-sided CHF.

In approximately 60% of dogs with MMVD, the mitral valve will be affected; 30% will have mitral and tricuspid valve degeneration, and 10% will be affected by tricuspid valve disease (Weir and Gordon, 2021).

Valvular disease is the most common cause of left-sided CHF in dogs, with a higher incidence in older dogs and small to medium-sized breeds, such as the Cavalier King Charles spaniel (Figure 3), miniature poodle and cocker spaniel. The majority of MMVD cases will go undiagnosed until clinical symptoms are noticed by the owner or when a vet first detects a murmur; therefore, it is important clients are made aware of the importance of annual checks, especially for breeds predisposed to heart conditions.

MMVD treatment involves eliminating CHF signs by using medication to resolve disease symptoms. Patients with right-sided CHF may require abdominal paracentesis to relieve ascitic pressure. MMVD is not curable, but treatment can increase the patient’s life expectancy.

The publication of the evaluation of pimobendan in dogs with cardiomegaly (EPIC) study results changed how preclinical MMVD is managed (Boswell et al, 2016).

The EPIC study showed a significant benefit in administering pimobendan in dogs with preclinical MMVD, before the onset of CHF, cardiac-related death or euthanasia. This means asymptomatic cases with cardiomegaly can be treated to delay onset of CHF.

CHF

CHF is not a structural heart disease; it is a consequence of it. CHF is a condition commonly seen in practice, and can account for up to 38% of all cases presented with dyspnoea (Linney, 2016).

CHF occurs when the heart has impaired pumping capability, associated with abnormal water and sodium retention. The condition ranges from mild congestion with few symptoms to life-threatening fluid overload and total heart failure.

The most important function of the circulatory system is to maintain adequate blood pressure. When the heart begins to fail, the body’s tissues do not receive sufficient blood supply for normal function. The body starts to stimulate compensatory mechanisms to normalise blood pressure. Cardiac output is improved by an increase in the heart rate and stroke volume via fluid retention.

Vasoconstriction causes an increase in systemic vascular resistance. This is called compensated heart failure. Any further deterioration leads to more fluid retention, which results in pulmonary oedema, ascites or pleural effusion. CHF can develop as an end consequence of many different diseases and may be either left or right-sided, depending on which side of the heart is diseased.

Left-sided CHF occurs due to disease affecting the left side of the heart (for example, MMVD). Congestion or pooling of blood not only occurs in the left atrium, but also in the vessels returning blood to the left atrium, and the pulmonary veins, which may result in pulmonary oedema. Clinical signs include coughing (due to compression of the mainstem bronchi by the left atrium), exercise intolerance, and tachypnoea or dyspnoea.

Treatment involves diuretics, inodilators or ACE inhibitors, antiarrhythmic drugs if required, reducing exercise, weight loss if required, and a restricted-sodium diet. In severe or acute cases, oxygen therapy may be required.

Right-sided CHF occurs due to disease affecting the right side of the heart (for example, tricuspid valve disease [TVD]). Congestion of blood occurs not only in the right atrium, but also in the vena cava, causing fluid accumulation in the abdomen and the chest cavity. TVD normally occurs in association with MMVD, and dogs with both mitral and tricuspid valve disease will have signs of both left and right-sided CHF. Clinical signs of right-sided heart failure include ascites, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, exercise intolerance, pale mucous membranes, jugular vein distension and weight loss.

Although a diagnosis of CHF carries a poor prognosis, with careful medical, weight, diet and exercise management, symptoms can be eased and progression slowed with a multimodal approach, possibly leading to median survival times in dogs between 6 and 12 months (Linney, 2016).

Nurse’s role in heart disease

VNs will assist the vet with all aspects of heart disease management, from diagnosis to treatment; therefore, it is important that VNs understand the requirements of patients with cardiac disease.

With many VNs running their own clinics and advising clients, it is important that they are able to recognise and detect early signs of heart disease, such as exercise intolerance, breathing issues or coughing, particularly in senior pets. VNs should also be competent at cardiac and lung auscultation, and be able to detect abnormal sounds. Any concerns should be forwarded to the vet for diagnosis.

A general understanding of the underlying condition and medication is beneficial when managing these patients to support clients and patients.

ECGs are an important part of monitoring and diagnosing heart disease. They demonstrate the electrical activity of the heart and show the heart’s rate and rhythm. VNs should be able to perform an ECG and identify a normal trace. VNs are often responsible for radiography and should, therefore, have an understanding of the views and positioning required for patients with heart disease. Most will require a minimum of one lateral view and a DV view. The ability to measure and monitor blood pressure trends and provide important data about patient cardiovascular status may help to define approach to treatment.

Blood pressure monitoring has become a vital part of small animal practice, and is often the responsibility of the nursing staff. Doppler echo is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of cardiac disease. It is particularly helpful in cases of pericardial effusion or cardiomegaly and can differentiate between MVD, DCM and pericardial effusion from congenital cardiac disease (Stafford, 2008).

Prevention of stress and keeping a patient cool is vital during diagnostic tests and examinations. Handling should be kept to a minimum, and a less-is-more approach should be employed – especially with cats.

Many patients with heart disease are senior, so thought should be given to the requirements of these patients. Elderly patients should be given plenty of padded bedding and opportunities to stretch the limbs, and care must be taken during restraint.

Other roles for VNs include administering medication prescribed by the vet and routine nursing aspects of in-patient care. Patients on diuretics should have increased frequency of walks to allow urination to ensure comfort. Cardiac cachexia is common in patients with CHF, so adequate energy intake is important; therefore, weight, body condition scoring and muscle scores (and recording the results) should be an integral component of every nurse check-up.

Diet is also an important factor in the management of cardiac patients. Patients with CHF may benefit from a diet with restricted sodium to help decrease water retention. Patients with mild cardiac disease may benefit from dietary supplementation of arginine, carnitine and taurine, which is thought to improve heart muscle blood flow.

Carnitine deficiency has been associated with myocardial disease in people, and its role in canine DCM has been of interest (Devi and Jarni, 2009).

In 2021, Purina launched Pro Plan Veterinary Diets CC CardioCare, a new diet containing a blend of nutrients to support heart function. Key elements of the Cardiac Nutritional Blend include carnitine precursors, antioxidants and medium-chain triglycerides. The latter provide an alternative energy source that is easy for the struggling heart to utilise. This nutrient blend has been supported by clinical research; a study by Li et al (2019) revealed it has the potential to delay or reverse the progression of preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD).

While the clinical research to date has focused on MMVD, the nutrients in CardioCare are recognised to be beneficial under conditions of cardiac stress, and the diet may prove a useful tool to provide support in a wider range of conditions. The diet can, therefore, be considered as part of the management plan for dogs with cardiac insufficiency.

While management and treatment starts in the practice, it is vital for both the patient’s quality of life and disease progression that this is continued at home.

One parameter owners can check themselves is their pet’s resting respiratory rate. Monitoring of resting respiratory rates is a key indicator to the severity of heart failure and in assessing the development or resolution of pulmonary oedema. Ideally, this should be done when their pet is asleep and after exercise.

Smart phone apps are particularly useful for owners to assess their dog’s respiratory rate at home. VNs can be instrumental in demonstrating how to monitor resting respiratory rates.

Once heart disease has been diagnosed and a care plan has been established, follow-up examinations are essential to assess the efficacy of the treatment. Follow-up checks will ensure compliance with the overall management and will aid assessment of the patient for progression in its condition, a need for a change in the medication, additional treatment, side effects, toxicity or adverse reactions to the drugs used.

The frequency of checks will be determined by the severity of the heart disease, the stability of the patient and owner compliance. Studies in human medicine have demonstrated attending nurse-led heart failure clinics following discharge can improve survival times and self-care behaviour of those patients (Strömberg et al, 2003), so it is likely regular nurse clinics would have the same impact.

Factors to consider in a cardiology nurse clinic include:

- Temperature, pulse, respiration, mucous membrane colour and capillary refill time.

- Weight check.

- Abdominal girth.

- Check sleeping respiratory rate chart.

- Optimise nutrition, check body muscle mass, body condition score, appetite, oedema.

- Run ECG if required.

- Check blood pressure.

- Take blood samples (biochemistry, haematology, electrolytes, pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; Bnp and troponin 1).

- Check owner compliance with medication.

Conclusion

The VN is in an ideal position to provide client support to ensure optimal cardiac patient care. With the support of a VN, successful management of heart disease patients can be achieved by proactively engaging clients in a care-giving role, whatever the condition being managed.