28 Mar 2016

Rebecca Newnham and Pedro Oliveira discuss a case of severe heartworm infestation in a canine and the surgical procedure to remove it.

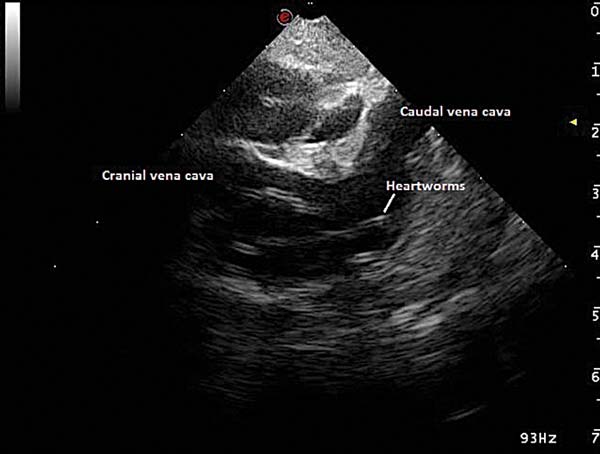

Figure 3. Heartworms being removed.

Heartworm disease is caused by infestation of the parasite Dirofilaria immitis. These parasites reside in the pulmonary arteries rather than the heart, except in cases of severe infestation. The fact they were historically found inside the right side of the heart at postmortem is why they were named “heartworms”.

The presence of adult worms inside the pulmonary vessels causes some degree of physical obstruction to blood flow and leads to pathological changes of the vessel wall that will depend on the immunological response mounted by the host and the degree of infestation. Significant pulmonary hypertension may occur, as well as inflammatory parenchymal lung disease, leading to “heartworm disease”.

This is a serious disease that may result in severe lung compromise, heart failure, other organ damage (such as renal) and death. Luckily, not all dogs infected with heartworms develop signs of the disease.

For the development and transmission of D immitis, an intermediate host is necessary. Stage 1 larvae (L1) are released in the blood and ingested by a mosquito. These larvae undergo two moults to L3 over the following few days before they are ready to infect another dog.

Maturation inside the mosquito depends on ambient temperature and is not possible when it averages 14°C or lower. For this reason, the disease is common in regions where the climate is favourable for mosquito populations and maturation of heartworm larvae. Presently, this is not the case in the UK, where the disease is not common.

However, with the number of dogs originating from other countries living in the UK increasing, heartworm and other diseases may be encountered. This report describes the management of the disease in a dog from Romania now living in the UK.

A 14kg female neutered crossbreed dog was presented for investigation of cough. She had lived her entire life in Romania and was later adopted by owners in the UK. Her age was estimated at four to six years. Her previous history was unknown.

On examination she was bright and alert. Her heart rate (60bpm to 80bpm) was lower than expected, but accompanied by normal mucous membranes and femoral pulses. A respiratory sinus arrhythmia was present and the respiratory rate at 30 breaths/minute was also in the normal limits, with a normal respiratory pattern. Diffuse crackles were obvious on auscultation. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

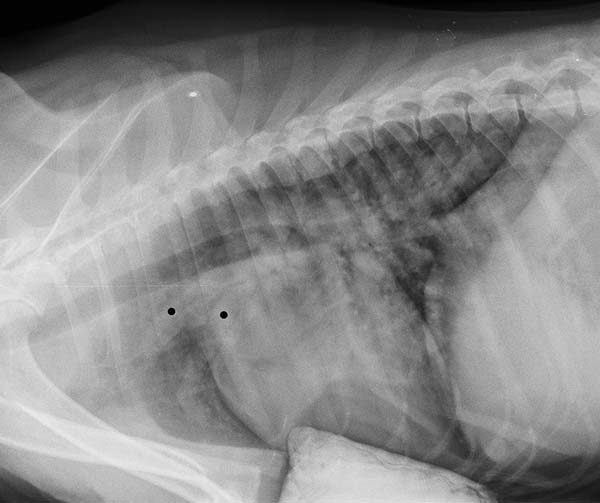

Chest radiographs revealed the presence of cardiomegaly, accompanied by significant dilation of pulmonary arteries that also appeared tortuous and truncated (Figure 1). A diffuse “patchy” interstitial/alveolar lung infiltrate was observed.

These changes raised suspicion of heartworm disease, taking into account she had been living in an affected region until recently. Infestation with D immitis was subsequently confirmed by antigen testing on blood.

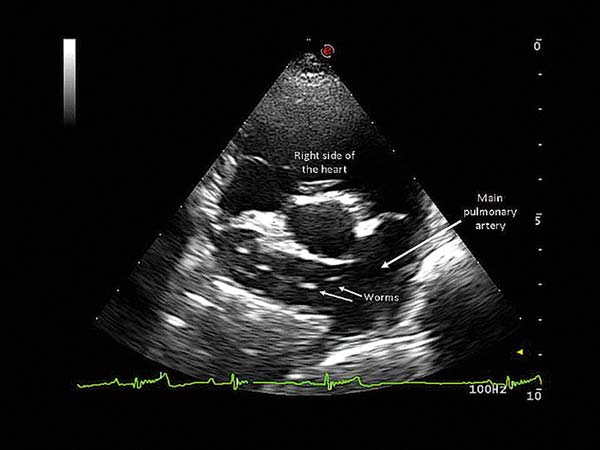

An echocardiographic examination was performed to assess cardiac size and function. Adult worms were visible inside the right pulmonary artery, which was enlarged (Figure 2).

Luckily, cardiac size and function appeared normal. A five-minute ECG revealed a normal sinus rhythm with a heart rate ranging from 80bpm to 100bpm.

Other diagnostic procedures included blood analyses, but these did not show significant findings.

The extent of the lung lesions observed radiographically suggested inflammatory lung disease was likely due to a combination of substantial infestation and significant immunological response.

Treatment was deemed necessary; however, adulticide treatment may lead to significant and life-threatening complications in these cases. Dead worm debris is carried by blood flow to terminal pulmonary artery branches, resulting in thromboembolism, while further obstruction may occur secondary to regional thrombus formation due to vascular endothelial damage.

Simultaneous death of several adult worms may lead to life-threatening respiratory compromise. The risks are higher in dogs with a greater number of worms and with severe pulmonary disease secondary to heartworm disease. Additionally, smaller patients are at a higher risk of complications due to the relative size of an adult heartworm (up to 25cm to 30cm) and their pulmonary vessels. In this case, and despite the absence of significant cardiac changes, the size of the patient, suspected worm burden and the degree of lung parenchymal disease raised concerns about the possibility of significant complications of adulticide treatment.

To improve the chances of an uneventful recovery, a decision was made to physically extract as many adult worms from the pulmonary artery as possible with a minimally invasive procedure prior to adulticide treatment. A two-week course of oral steroids was administered in an attempt to reduce the amount of inflammation and improve lung function prior to anaesthesia for worm extraction.

The procedure was performed under general anaesthesia, with the patient in left lateral recumbence, and cardiac catheterisation was performed via the right jugular vein.

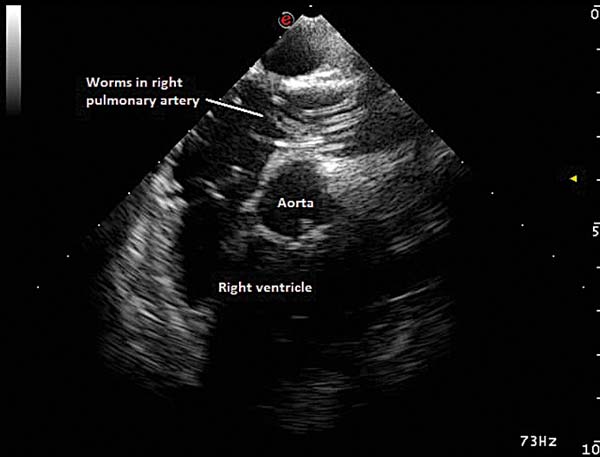

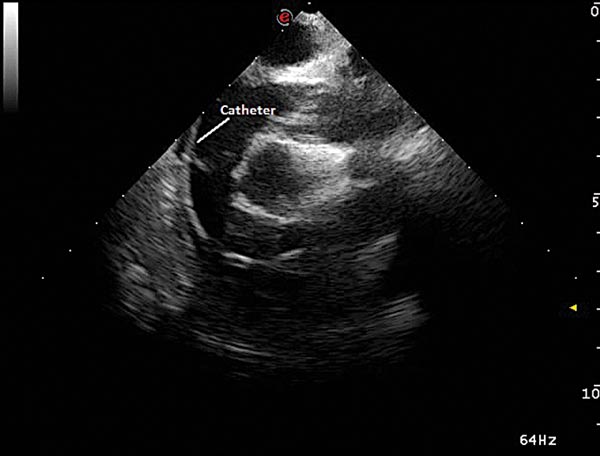

Fluoroscopy and transoesophageal echocardiography were used for guidance and monitoring purposes. A sterile endoscopy basket retrieval device was positioned in the right pulmonary artery and used to retrieve adult worms (Figure 3). The aim was to repeat this operation until worms were no longer visible echocardiographically (Figures 4a and 4b).

However, after the removal of approximately 10 worms, marked hypotension was observed. This was caused by accidental release of several worms from the basket during a retrieval attempt inside the right atrium and across the tricuspid valve (Figure 5). This caused occlusion and a marked drop in venous return to the heart.

Aggressive fluid therapy was used in the form of crystalloid and colloid boluses to improve venous return, and the worms were removed as quickly as possible from the heart. This was successful in achieving patient stabilisation and a decision to continue the procedure was made after time for recovery (approximately 30 minutes).

Another six retrieval attempts were performed, resulting in the removal of five additional worms. However, the presence of frequent ventricular arrhythmias and persistent hypotension following the episode mentioned led to the decision to stop the procedure, despite the fact all visible worms had not been removed. The occurrence of arrhythmia and myocardial failure is a possible complication of this procedure and the mortality rate has been reported at 20%.

The patient recovered well from anaesthesia without any complications. She was discharged the following day with a five-day course of cephalexin and omeprazole. Two weeks later, a four-week course of doxycycline was started prior to adulticide treatment with long-term ivermectin (“slow-kill” method). The aim was to target symbiotic bacteria of the genus Wolbachia harboured by heartworms.

It has been shown anti-Wolbachia treatment reduces the ability of the worms to reproduce, the infectivity of the L3 larvae and the microfilariae burden while it potentiates the “slow-kill” efficacy. In fact, studies have shown the combination of doxycycline and ivermectin provides better results than either drug alone. Admittedly, this choice of medical treatment is controversial.

Treatment with melarsomine dihydrochloride is the preferred option and offers better results. With the “slow-kill” method it may take up to two years of continuous administration of ivermectin to eliminate 95% of adult heartworms, and the potential for selection of resistant subpopulations of heartworms exists. However, the likelihood of severe complications is much lower and the main reason for selection in this case following a discussion with the owners.

This treatment is ongoing and significant clinical improvement was noticed since the procedure, with resolution of cough and an improvement in activity levels.

An increase in the number of dogs living in the UK originating from other European countries has been observed. As a consequence, diseases not commonly seen here may be encountered and it is important we are aware of this. This report describes an interesting case of such a disease.