28 Oct 2025

Houseplant toxicosis in cats and dogs

Lotfi El Bahri DVM, MSc, PhD discusses diagnosis and treatment of Dieffenbachia species poisoning

Image: wpw / Adobe Stock

Plants are an important part of the decor of homes. However, indoor plants and ornamentals are a common source of potential toxicosis for pets: chewing on or ingesting these plants can result in toxicoses.

Data from the poison control centres of European countries confirm the importance of plants as causative agents of pets poisoning (up to 13%). However, many houseplant poisonings are underdiagnosed by veterinarians.

The objective of the article is to help practitioners in the diagnosis and treatment of poisoning in companion animals related to houseplant exposures.

Dieffenbachia (dumb cane) species is an herbaceous perennial plant belonging to the Araceae family, which naturally grows in central and south America regions.

The plant was named by the Austrian botanist Heinrich Wilhelm Schott to honour his head gardener of the Schönbrunn Palace, Joseph Dieffenbachia, who was in charge at the summer residence of the Habsburg rulers, in Vienna.

The common name, dumb cane, refers to the local toxic effects of the sap of this plant, which causes temporary inability to speak if it is ingested.

A commonly found decorative plant in homes and playgrounds, Dieffenbachia species is appreciated for its particularly attractive colourful leaves, which can be grown in low-light conditions, away from full sun exposure. Fifty species of Dieffenbachia species exist, some of which include D seguine, D maculata, D amoena and D picta.

Botanical identification

Dieffenbachia species, a robust herbaceous shrub, has stout, straight, thick stems with long necks, simple and alternate green leaves containing white spots and fleck, with a variety of patterns of patches or blotches in colours of cream, white or yellow. It rarely develops flowers or fruits as an indoor plant.

What is the toxicity and mechanism of toxicity of Dieffenbachia?

The toxic properties of Dieffenbachia species have been utilised by indigenous tribes of hunters in the upper Amazon (Peru) to make arrow poisons. Common genera of the Araceae family such as Dieffenbachia; Philodendron (Philodendron scandens, sweetheart vine); Monstera (Monstera deliciosa, Swiss-cheese plant); Alocasia (Alocasia antiquorum, elephant ear) are highly toxic to cats. Cats are more sensitive than dogs. Young animals are more frequently affected than adults.

Cases of home accidents of pets or children (colourful leaves are attractive) exposed to Dieffenbachia species plant are frequently reported. All parts of the plant (stems, leaves, sap) are toxic. Dieffenbachia species can have harmful animal effects as a result of ingestion, chewing or contact. The toxicity may be caused by a combination of mechanical and chemical effects. Dieffenbachia species has idioblasts, cylindrical thick-walled cells containing high amounts of tiny (3µm), needle-shaped, insoluble calcium oxalate (raphides) arranged parallel in compact bundles at both ends. Calcium oxalate (C2CaO4) needles have inflammatory properties.

When chewing, eating or biting the plant, the idioblasts are ruptured, and numerous sharp calcium oxalate crystals are released and penetrate with force in the tissues of the mouth, tongue, oropharynx, laryngeal region, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, upper airway, skin and eye, producing microtrauma, severe irritation, strong inflammatory reaction and immediate intense pain.

The presence of proteolytic enzymes in the idioblasts also induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukine-6), produced by activated macrophages as inflammatory mediators of acute inflammatory cytokines that promote inflammation reactions. Another toxin of Dieffenbachia species is L-asparaginase, an immunogenic protein (molecular weight of about 37 kilodaltons), which potentiates histamine release, inducing severe allergic reaction.

What are the clinical features of Dieffenbachia poisoning in pets?

Clinical features are dependent on the type of contact and amount of exposure. Following ingestion, poisoning occurs quickly, with clinical signs appearing within five minutes. They include the following.

Oral signs:

- hypersalivation

- intense burning of mouth

- pawing at mouth (pain in the oral cavity)

- swelling of the tongue

- oedema on epiglottis with occlusion of the larynx airway passage (dysphagia and difficulty breathing)

GI signs:

- nausea

- vomiting

- diarrhoea

- abdominal pain

- distended stomach (full of plant material)

Respiratory signs:

- inspiratory stridor

- marked dyspnoea

- respiratory distress

Death can occur by upper airway obstruction by plant material. In case of skin contact, rash, swelling, erythema and dermatitis are observed.

Eye exposure to Dieffenbachia species induces ocular symptoms, usually developing in five to 18 hours, including serious pain, chemosis, blepharospasm, lacrimation, keratoconjunctivitis and corneal ulcers.

In cats, systemic toxicity can occur, including renal signs (haematuria or proteinuria) progressing to acute renal failure within one to two weeks and neurologic signs (muscle contractions).

What is the approach to managing Dieffenbachia poisoning in pets?

No specific antidote is available. Treatment is largely symptomatic and supportive, and depends on the type of contact and the severity of clinical signs. In cats, Dieffenbachia species poisoning can be life threatening.

Supportive therapy

Treating acute respiratory distress

Attention to airway and breathing is paramount. Upper airway obstruction by the plant can be life threatening.

Oxygen saturation of less than 93% and an arterial partial pressure of oxygen below 70mmHg should prompt oxygen supplementation.

Affected animals should be intubated with a cuffed endotracheal tube to keep the airway clear and provided oxygenation.

The first treatment is immediate oxygen supplementation by high-flow oxygen therapy (HFOT). HFOT is the administration of warm humidified oxygen via nasal prongs. HFOT is an effective method of delivering high volumes and pressures of oxygen.

HFOT bridges the gap to mechanical ventilation, is less invasive than ventilation, and is generally more cost effective. It allows the delivery of higher flow rates of oxygen (4L/min to 60L/min with some devices).

The flow rate is set to meet or exceed the inspiratory flow demand of the patient.

In normal mesocephalic dogs (for example, the golden retriever, Labrador retriever and German shepherd dog), the average flow demand is approximately 500ml/seconds to 1,000ml/seconds. Brachycephalic dogs (for example, the boxer and bulldog) may have lower flow demands.

Antimicrobial administration may be considered: ampicillin plus clavulanate 30mg/kg to 50mg/kg IV every six hours. Also, administer corticosteroids to reduce inflammation in the airways: dexamethasone sodium 0.15mg/kg IV single dose every 24 hours. Alternatively, administer methylprednisolone sodium succinate 20mg/kg to 30 mg/kg IV, which may be repeated at four to six hours for 24 to 48 hours.

Treating oral pain

Wrap a cold compress and apply it to the dog’s mouth or cheeks. Cold compresses and ice packs are effective to relieve inflammation in dogs. Apply topical administration of promethazine gel (lidocaine is contraindicated, as vasodilation can occur).

Opioid analgesics may be required: buprenorphine 5µg/kg to 20µg/kg IV, IM every six to 12 hours in dogs; in cats, 20µg/kg to 40µg/kg IV, IM every eight hours.

Treating eye pain and infection

Eye pain warrants prompt treatment. The cornea contains a high density of nociceptors, producing a marked pain response to traumatic stimuli. Administer local anaesthetic such as tetracaine hydrochloride 0.5% eye drops: two drops in the eye affected every 10 minutes for up three doses.

Administer moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution 0.5%: one to two drops in the affected eye, two times a day for seven days.

Treating allergic reaction

Administer H1 antihistamines: diphenhydramine 2mg/kg to 4mg/kg IM, SC every eight to 12 hours as needed. Contraindicated for kittens or small cats.

Alternatively, administer hydroxyzine: 0.5mg/kg to 2mg/kg IV every six to eight hours.

Treating vomiting

Severe vomiting should be treated by antiemetic serotonin antagonists with powerful activity such as ondansetron: 0.5mg/kg to 1mg/kg IV slow bolus (two to three minutes) every eight 12 hours (used cautiously in dogs with the MDR1 mutation) or dolasetron: 0.6mg/kg IV slow bolus every 24 hours.

Do not use maropitant (neurokinin 1 antagonist) if the patient is at risk for a foreign body obstruction. Metoclopramide (dopamine antagonist) is contraindicated (excitatory effects can occur).

Treating GI injury

Sucralfate (salt of sucrose complexed to sulfated aluminium hydroxide) binds to ulcer sites of the GI tract, stimulates healing and protects them.

Give an initial loading dose of 3g to 6g orally four times a day and then 0.5g to 1g on an empty stomach at least one hour before meals.

Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole (0.5mg/kg to 1mg/kg IV every 12 hours) or pantoprazole (1mg/kg IV) or lansoprazole (0.6mg/kg to 1mg/kg IV every 24 hours) can be used.

IV fluid therapy

Fluid therapy is recommended if severe vomiting or dehydration occurs. IV infusion is the preferred means of delivering fluids to severely dehydrated animals.

Fluid therapy with IV sterile sodium chloride 0.9% should always be the first-line management.

The volume (ml) of fluid needed to correct dehydration is calculated from the following formula:

Percentage of dehydration × bodyweight (kg) × 1,000

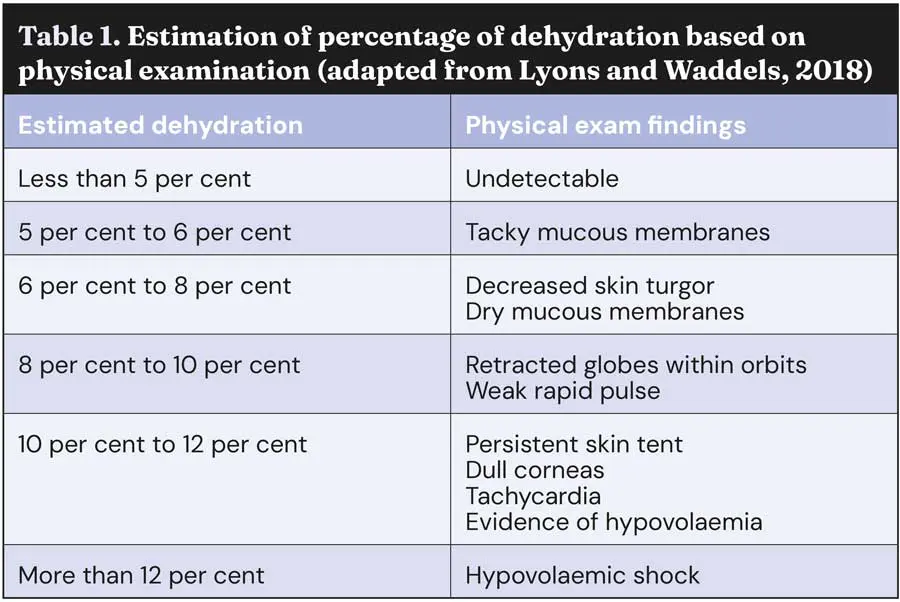

Percentage dehydration can be estimated by examining mucous membrane moisture, skin turgor, eye position and corneal moisture, as described in Table 1.

It is recommended that one-quarter to one-half of the estimated dehydration deficit is replaced over the first two to four hours, with the remaining dehydration deficit and maintenance isotonic volumes administered over the subsequent 20 to 22-hour period. Adequate hydration and urine output (1ml/kg/hour to 2ml/kg/hour) should be ensured.

Preventing secondary bacterial infections

A broad spectrum antibiotic is recommended, such as cephalexin: 15mg/kg to 35mg/kg IM every 12 hours for seven days.

Detoxification therapy

Inducing vomiting is contraindicated (sharp crystal calcium oxalates pose a high risk for oesophageal or gastric perforation). Gastric lavage is also contraindicated. Administration of activated charcoal is not recommended (no significant benefit).

The mouth should be rinsed with tepid water for at least 10 minutes to clear any plant residue. The mouth can be flushed using a detachable shower nozzle. It is best not to squirt the water directly into the back of the throat because of the risk of aspiration.

The water source should be positioned at the commissure of the lips and directed rostrally. Oral lavage should not be performed in an animal that cannot swallow or that is unstable (for example, tremors, dyspnoea).

Dissolve calcium oxalate crystals (soluble in acidic solutions) present in the oral cavity, oesophagus or GI tract by administration of lime juice of one citrus fruit with a lot of sugar in dogs.

However, keep in mind that the lime juice is toxic to pets (large amounts of citric acid: 5g/100ml to 7g/100 ml, as well as essential oils such as limonene and linalool).

Ocular exposures should be washed immediately with abundant saline for at least 15 minutes to reduce damage by sharp calcium oxalate penetration. Fluorescein staining and slit lamp examination is recommended, followed by ophthalmology consultation if evidence of keratoconjunctivitis and/or corneal injury is present.

Corticosteroids are contraindicated both topically and systemically when a corneal ulcer is present. Affected skin should be washed with soap and water and then rinsed thoroughly. For patients with severe exposure with the plant, a longer recovery time (one to two weeks) may be necessary.

Place Dieffenbachia species and genera of the Araceae family out of the reach of children and pets. Be alert for toddlers and pets that might eat or chew on the leaves or the stems.

The owners should know about the plant and its toxic/life-threatening effects. Do not keep Dieffenbachia species in nearby surroundings, and if at all keeping it, wear gloves while handling the plant.

Always make sure to wash your hands after handling this plant and keep your hands away from your eyes and mouth.

A liquid diet is recommended to support nutrient restoration.

Drinking can be encouraged by placing flavouring in the water (beef or chicken stock mixed and made into ice cubes and added to water).

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 43, Pages 14-17

References

- Arditti J and Rodriguez E (1982). Diffenbachia: uses, abuses and toxic constituents: a review, Journal of Ethnopharmacology 5(3): 293-302.

- Bertero A, Fossati P and Caloni F (2020). Indoor companion animal poisoning by plants in Europe, Frontiers in Veterinary Science 7: 487.

- Burke MJ and Zalewska-Szewczyk B (2021). Hypersensitivity reactions to asparaginase therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: immunology and clinical consequences, Future Oncology 18(10): 1,285-1,299.

- Caloni F, Cortinovis C, Rivolta M, Alonge S and Davanzo F (2013). Plant poisoning in domestic animals: epidemiological data from an Italian survey (2000-2011), Vet Record 172(22): 580.

- Chong SH, Wang Ch’ng T and Mustapha M (2022). Dieffenbachia-induced transient crystalline keratopathy: a case report and review of previously reported cases, Cureus 14(1): e21146.

- Cumpston KL, Vogel SN, Leikin JB and Erickson TB (2023). Acute airway compromise after brief exposure to a Diffenbachia plant, Journal of Emergency Medicine 25(4): 391-397.

- Fochtman FW, Manno JE, Winek CL and Cooper JA (1969). Toxicity of the genus Dieffenbachia, Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 15: 38-40.

- Loretti AP, Ilha MRDS and Ribeiro RE (2003). Accidental fatal poisoning of a dog by Dieffenbachia picta (dumb cane), Veterinary and Human Toxicology 45(5): 233-239.

- Lyons BM and Waddell LS (2018). Fluid therapy in hospitalized patients, part 1: patient assessment and fluid choices, TVP January/February: tinyurl.com/2kxv96pw

- Peterson K, Beymer J, Rudloff E and O’Brien M (2009). Airway obstruction in a dog after Dieffenbachia ingestion, Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 19(6): 635-639.

- Plumb DC (2011). Plumb’s Veterinary Drug Handbook (7th edn), Wiley-Blackwell, Wisconsin.

- Siroka Z (2023). Toxicity of house plants to pet animals, Toxins 15(5): 346.