2 Sept 2025

Ian Wright BVMS, BSc, MSc, MRCVS considers the potential risks professionals face in the practice and how they can be mitigated.

Image: auremar / Adobe Stock

Working with and around pets in the veterinary practice setting can expose veterinary professionals to potentially zoonotic parasites. These pathogens may be transmitted through direct contact with pets, indirect surface transmission, aerosols or via vectors.

Examples of pathogens transmitted through direct and indirect contact are dermatophytes (ringworm), mites (Sarcoptes or Cheyletiella species), Bartonella species (via flea faeces) and Brucella canis. Bacteria such as Brucella and Bartonella species may also be transmitted via the aerosol route.

Fleas can easily become established in veterinary practice buildings, leading both to physical irritation and transmission of flea-borne pathogens such as Rickettsia felis. Ixodes species and Dermacentor reticulatus ticks are unlikely to become established indoors in the UK.

Unfed ticks present on pets and wildlife casualties, however, can be shed into the environment and subsequently bite veterinary staff. This in turn can lead to tick-borne pathogens such as Borrelia species, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and tick-borne encephalitis virus being transmitted.

These zoonotic risks, however, can be reduced in the veterinary practice workplace with a few simple precautions.

Bites and scratches from cats and dogs can lead to the introduction of bacterial and fungal infections via compromise of the skin barrier.

As well as generalised bacterial infections, cat bites and scratches are a particular risk for Bartonella henselae (the cause of cat scratch disease). Transmission of this pathogen occurs via flea faeces contaminating nails or being present in saliva.

Planning to minimise the risk of bites and scratches is, therefore, important before any procedures are carried out on pets. Recording in clinical notes any history of previous biting or scratching behaviour, and discussing likely behaviours in the consult room with clients, are crucial to aid planning, but should not be wholly relied upon.

Other factors to consider before interaction with pets include the following.

Thorough handwashing after patient examination, injury or contamination with bodily fluids or flea dirt (Figure 1), and before eating, is essential in reducing the risks of zoonotic pathogen transmission. It is superior to the use of alcohol-based lotions and hand wipes due to the limited penetration of alcohol into organic material such as blood and faeces.

Skin-penetrating bites, scratches and other lacerations should be immediately washed to minimise contamination. While it is tempting to complete examinations and procedures before personal wound cleaning, even short delays can allow pathogens such as ringworm and Bartonella species to establish. The use of moisturising soaps or moisturising after washing helps to maintain a healthy skin barrier.

It is also important to wear gloves while disinfecting potentially contaminated surfaces with zoonotic agents. Surfaces should be cleaned and disinfected after contamination with bodily fluids, potentially contaminated fur or nail clippings, and flea dirt. Contaminated equipment such as grooming equipment and flea combs should not be left on surfaces and thoroughly cleaned (Figure 2).

Disinfectants licensed for use in veterinary practices often contain a combination of active ingredients for antiviral and antibacterial efficacy, and will be effective against most parasite life stages. Ovicidal efficacy is important where contamination with parasite eggs or protozoan cysts is suspected, such as in faecal-contaminated kennelling and exercise runs.

The extent to which personal protective equipment (PPE) is required for handling individual patients should be made on the basis of a risk assessment. Risks to consider include likelihood of zoonotic infection, confirmed zoonotic pathogen diagnosis, and likelihood of transmission and environmental contamination.

Gloves should be worn when handling any animal with evidence of infectious skin disease, open wounds or ectoparasite infestation, as well as when contact with bodily fluids is likely. Gloves should be changed between examinations of individual patients, with contact between the skin and the outer glove surface being avoided during removal. Hands should be washed as soon as the gloves are removed. Facial protection should be worn whenever exposure to splashing fluid or aerosol contamination is likely, such as when flushing wounds or during postmortem examinations. This may take the form of a face mask and goggles, or a full facial shield, depending on the level of risk.

Protective gowns or aprons are vital when caring for or examining patients with confirmed zoonotic infections that are likely to be transmitted through contact or bodily fluids. Contaminated clothes should be promptly changed if soiled.

Tick and flea bites are an underestimated source of pathogen transmission in veterinary practice.

Although Ixodes species ticks are unlikely to become established in veterinary practices, many wildlife casualties, as well as cats and dogs, exposed to large numbers of ticks are likely to have unfed adults and nymphs in their coats. These may easily be brushed off into the environment or on to veterinary staff. Once attached, if not removed quickly, ticks may transmit a number of zoonotic tick-borne pathogens including Borrelia species, tick-borne encephalitis virus, small Babesia species and Anaplasnma phagoctophylum (Abdullah et al, 2016).

Veterinary staff should check themselves for ticks after handling heavily infested pets or wildlife casualties, such as hedgehogs, which may have many unattached nymphs on their bodies which are only a few millimetres long.

Any ticks removed or found in veterinary premises should be identified. This is important, as it will indicate which tick-borne pathogens the tick was potentially able to transmit and whether infestation of the practice is likely. In the case of Ixodes species and Dermacentor reticulatus, this is not a concern, but in the case of Rhipicephalus sanguineus from travelled or imported pets, this is a significant possibility.

Ticks may be identified using keys, such as one provided by The European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites UK and Ireland (tinyurl.com/ysnc8nef), or they can be sent to the UK Health Security Agency’s Tick Surveillance Scheme (tinyurl.com/3m3u2mjf).

Cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis) are a source of human irritation and bite reaction, and can transmit zoonotic pathogens such as Bartonella henselae and Rickettsia felis. They are the most common fleas found on domestic cats and dogs (Abdullah et al, 2019) due to their adaptation to the environmental conditions in human households and ability to live on a wide range of mammals, including cats, dogs, humans, rabbits and ferrets. This means infested pets and wildlife casualties are likely to be regular visitors to veterinary practices, with the potential for cat flea infestations to establish.

Discovery of fleas away from animals and flea bites (Figure 3) are indicators of possible practice infestation. Flea infestations in practice can be treated using pyrethroids and growth-regulating sprays.

Care must be taken to avoid spraying at times when pets sensitive to pyrethroids, such as cats, reptiles and invertebrates, are present. Instructions should be followed carefully to ensure unintended exposure of people and pets to pyrethroids does not occur.

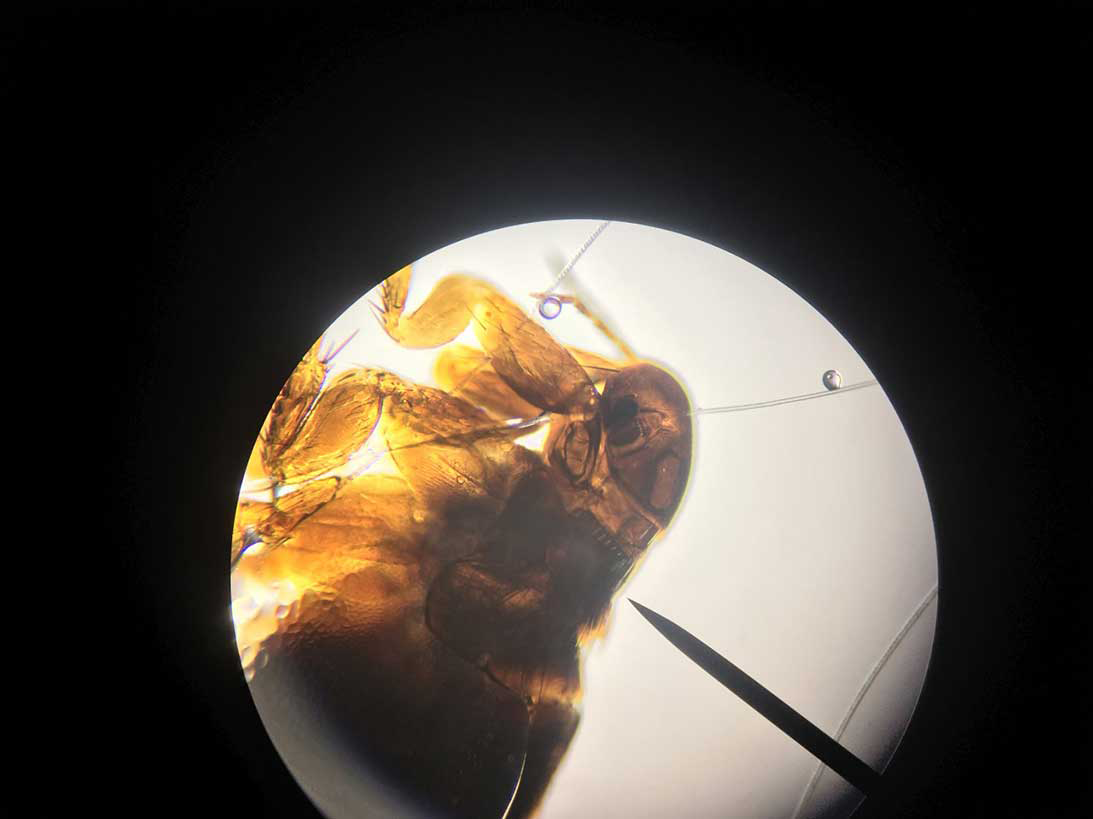

It is also to important examine any flea found in the practice under the microscope to distinguish them from fleas of wildlife. The heads of adult fleas may bear a posterior (pronotal) or ventral (genal) row of dark spines known as combs. Cat fleas have both genal and pronotal combs, and a characteristic elongated head, with the head being twice as long as it is tall.

In bird fleas (Figure 4) and fleas of rodents and badgers, the pronotal combs are present, but genal combs are absent. Bird and rodent fleas may come from nests in or adjoining the practice, and require the source of the infestation to be identified and treated or removed.

Concerns have arisen around the increasing numbers of imported dogs being found to be carrying Brucella canis, a Gram-negative zoonotic bacterium. Infection in domestic dogs is typically associated with reproductive abnormalities including infertility, abortion, endometritis, epididymitis and orchitis and scrotal oedema.

A wide range of non-reproductive conditions can also occur though, including chronic uveitis, endophthalmitis and discospondylitis. The consequences of zoonotic disease can be significant – especially in the immune-suppressed – but needs to be balanced against a low risk of transmission in most cases.

Neutered dogs pose minimal risk of transmission. In entire dogs, reproductive fluids pose the highest risk of transmission, but a small risk of transmission also exists via other bodily fluids such as urine, blood and saliva. Dogs that are serologically positive, or have history of being imported from abroad and have relevant clinical signs, should be handled with appropriate PPE.

Contamination of surfaces with bodily fluids from these dogs should be cleaned and disinfected. Further advice on managing B canis risk in the workplace can be found at tinyurl.com/abmsvdfk

While not receiving as much attention as zoonotic infection in the workplace from viruses, MRSA and food-borne bacterial pathogens, parasites and vector-borne pathogens pose a significant risk. General principles of hygiene, protective clothing, safe animal handling and pest control will help to keep veterinary professionals and the wider veterinary practice team safe.

References

Abdullah S et al (2016). Ticks infesting domestic dogs in the UK: a large-scale surveillance programme, Parasites and Vectors 9(1): 391.

Abdullah S et al (2019). Pathogens in fleas collected from cats and dogs: distribution and prevalence in the UK, Parasites and Vectors 12(1): 71.