10 Jun 2025

James Haseler BVSc, DipEVDC, MRCVS explores how professionals can spot this condition and treat it, including advice on home care.

Image: encierro / Adobe Stock

Periodontal disease is the most commonly diagnosed condition in dogs, with a reported average of 9.3% to 12.52% within the UK population (Gawor et al, 2018).

It is not a dental disease, rather a disease of the periodontium and is comprised of gingivitis and periodontitis.

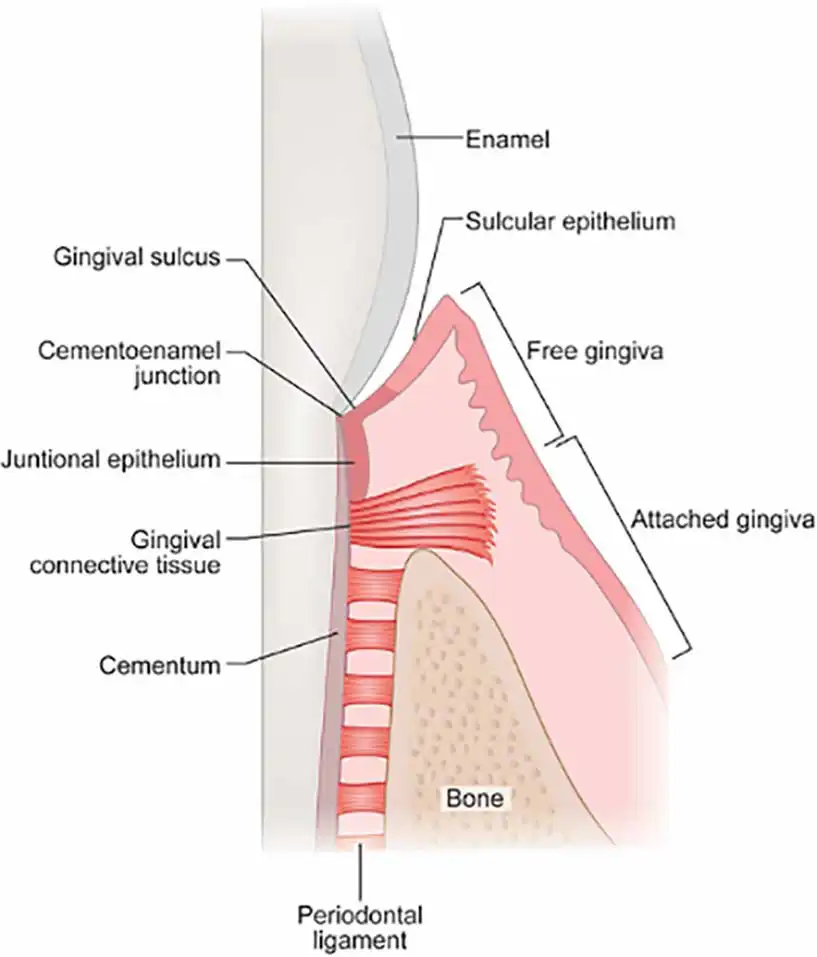

The periodontium consists of the gingiva, periodontal ligament and the alveolar bone. Gingivitis is defined as inflammation of the gingiva and can have multiple causes, such as trauma and irritation, as well as periodontal disease. Gingivitis is a reversible condition and can be reversed with appropriate treatment and home care.

Periodontitis is a progression of disease into the tissues surrounding the teeth (the periodontium) and is associated with bone loss. Periodontal disease cannot be fully reversed, but can be managed with comprehensive treatment and ongoing home care. Gingivitis can progress into periodontitis if not managed correctly.

With the aid of this article, I hope that you will be able to diagnose periodontal disease, as well as be able to provide treatment options.

As stated previously, the periodontium consisted of the gingiva, periodontal ligament and alveolar bone.

The gingiva consists of the attached gingiva, which is firmly attached to the alveolar bone, and the free gingiva, which forms the gingival sulcus. The gingival sulcus is a circumferential linear groove around the teeth and this is what is assessed when performing periodontal probing. The sulcus depth in dogs varies from 1mm to 3mm in depth; however, other factors such as the tooth type and dog size should be taken into consideration (for example, a sulcal depth of 3mm in a 40kg dog would be considered normal; however, the same depth on a small premolar tooth in a 4kg dog should be considered abnormal).

The gingiva is attached to the tooth at the cementoenamel junction and this attachment consists of two layers: the junctional epithelium and the gingival connective tissue (Figure 1).

This attachment is known as the biologic width and should be at least 2mm to maintain a healthy seal around the tooth. It is defined as the distance from the bottom of the sulcus to the crest of the alveolar bone; however, clinically the mucogingival junction can be used as a marker for the alveolar bone.

Any tooth where the biologic width is less than 2mm should be considered compromised and will require treatment (Figure 2).

There is a common misconception that bacteria invasion into the gingival tissues causes periodontitis; however, this is not true.

It is, in fact, the inappropriate response of the gingiva to the presence of bacteria and other pathogens. No specific bacteria has been isolated as a causative bacteria in periodontitis, but it has been shown that there is a shift in the microflora from a mainly Gram-positive population to a mainly Gram-negative population, with an increase in anaerobes and facultative anaerobes (Niemiec et al, 2022).

Early gingivitis has been shown to occur around one week after plaque accumulation. This inflammation causes gingival oedema and pseudopocket formation, which in turn increases plaque retention.

Macrophages and neutrophils secrete enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases, which cause destruction of extracellular matrix and stimulate the formation of pocket epithelium. This epithelium is friable, and this is why teeth with moderate to severe gingivitis bleed on periodontal probing.

At this point, there is still no bone destruction and the disease is still classed as gingivitis. However, as the process progresses, the collagen and extracellular matrix destruction extends into the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. This causes resorption of alveolar bone and migration of the junctional epithelium apically, causing a deepening of the periodontal pocket. This is now periodontitis.

The reason why certain breeds are more susceptible is most likely multifactorial, with breed, size and oral hygiene all playing important roles. There may be also a genetic component to the disease, but this has not yet been proven. Smaller dogs are more predisposed to the disease, with 98% of Yorkshire terrier breeds having at least tooth with periodontitis at 37 weeks of age (Wallis et al, 2019).

Another study revealed that periodontal disease was one of the most prevalent diseases of the greyhound and miniature schnauzer, with 39% and 17.4% being affected, respectively (O’Neill et al, 2019a; 2019b). A later study showed that breeds with the highest odds included the toy poodle, King Charles spaniel and greyhound (O’Neill et al, 2021). The dachshund has also been shown to be prone to periodontal disease, with dogs being three times more predisposed to oronasal fistula formation compared to similar size breeds (Sauvé et al, 2019).

Identification of periodontal disease starts with a conscious oral examination and detailed history. You can get a lot of information from history taking. A lot of clients do not suspect any discomfort associated with oral disease; however, periodontal disease is painful and dogs will show subtle signs.

These signs can include being less energetic, avoiding certain foods, avoiding play, sleeping more, chewing on specific sides and rubbing the face. Other more obvious clinical signs include bleeding gums, halitosis, pain and hypersalivation.

Conscious oral hygiene examination is useful, but you can only assess around 25% of the oral cavity conscious and a lot of dogs with periodontal disease are head shy or do not tolerate it.

Decision making for treatment of periodontal disease is multifactorial. Prior to embarking on treatment, I recommend discussing with the owner about oral home care and whether they would be able to manage with regular brushing.

If the dog is very head shy or the owner does not believe that they can perform sufficient oral home care, then periodontal therapy may not be the best option for the patient. Also, the owner should be made aware that follow-up imaging and examination is recommended, and so if they cannot commit to follow up, periodontal therapy may not be appropriate, and extraction of the diseased tooth would be recommended.

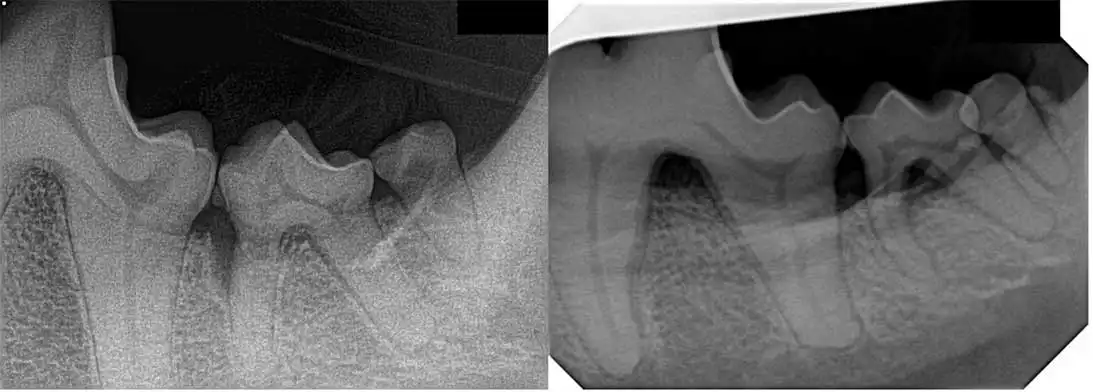

Dental radiography is key in determining which treatment method would be required. You need to determine whether the tooth in question has horizontal or vertical bone loss.

In most cases, regenerative therapy can only be performed on areas of vertical bone loss compared to horizontal bone loss where flap surgery to lower the level of the gingival margin is required (Figure 3).

Finally, periodontal probing is an important diagnostic tool for decision making. The sulcus of each tooth should be probed at six different points, at least.

Treatment of periodontal disease starts with diligent cleaning of all sides of the teeth, paying particular attention to the removal of all of the subgingival plaque and calculus. This can be an effective treatment for gingivitis, but it is recommended for the owners to continue with oral home care to maintain the periodontal health.

Unfortunately, periodontitis cannot be treated with professional dental cleaning alone and more invasive methods are required. The treatment method depends on the extent of bone loss and this should be assessed with your dental radiographs.

For minor bone loss and periodontal pocket formation, root planing can be performed. This can either be performed closed (without creating a flap) or open (surgical exposure of the pocket). If the periodontal pocket probing depth is greater than 5mm, closed root planing cannot be performed effectively, and so more invasive treatments, such as open root planing, should be considered.

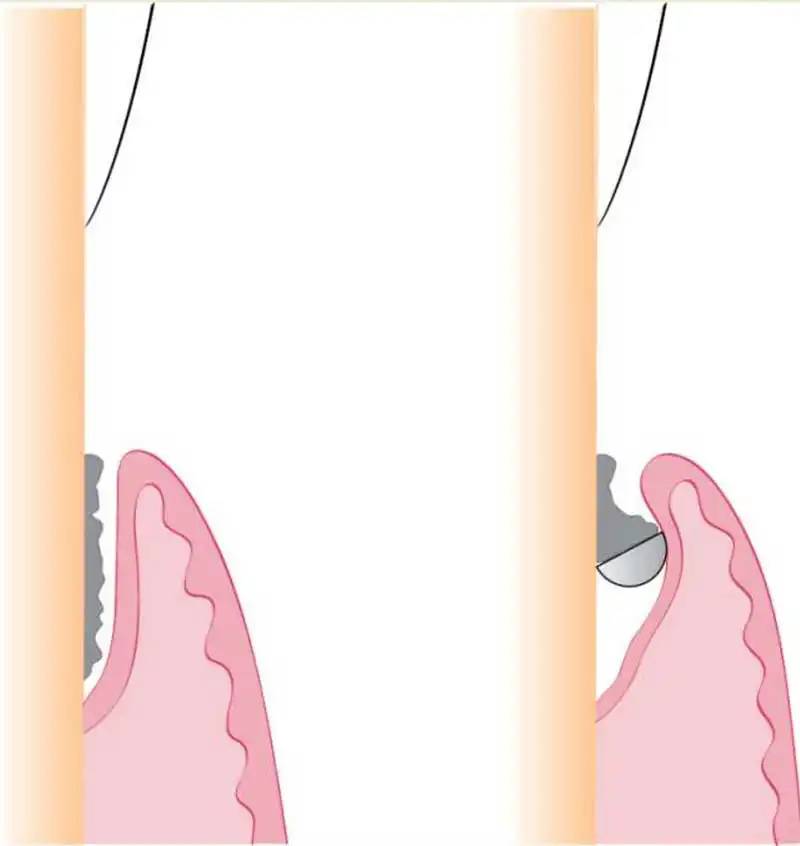

Root planing involves debridement of the pocket epithelium and any granulation tissue, as well as cleaning the denuded root to remove any debris. This is achieved using a subgingival curette (Figure 4), which is a single-edged instrument designed to be inserted into the gingival sulcus without damaging the surrounding tissues. This is different to a supragingival scaler, which is double edged and should only be used on hard tissues.

There are also dedicated attachments for piezoelectric scalers, which can be used instead of a curette. The curette should be passed into the pocket and when it is at the bottom of the sulcus, the blade is rotated, so that it engages against the tooth (Figure 5). The blade is then pulled coronally to remove the plaque and calculus from the root surface.

Once the tooth root is sufficiently cleaned, the curette should be turned around and, with the aid of digital pressure from the outside of the pocket, engage with the epithelium and perform a few gentle upward strokes to remove the diseased tissue. The free gingiva is delicate, so take care not to over-debride the soft tissues.

Once the pocket is cleaned, the area should be rinsed with sterile water, saline or chlorhexidine. In large defects, grafting materials such as regum (Gawor et al, 2022) can be placed to work alongside the formation of a blood clot to encourage regrowth of the periodontal tissues.

However, in certain very large defects, placement of a graft may not be efficient to completely regenerate the tissues so that there is a stable attachment. The reason for this is the periodontal tissues grow at different rates, with the desirable tissues (periodontal ligament and bone) taking longer than the less desirable tissues (junctional epithelium and gingival connective tissue).

Because of this difference in growth rate, treated defects tend to be refilled with fast-growing tissue rather than a stable periodontal attachment.

To prevent this, a membrane can be placed on top of the grafting materials to act as a barrier for the epithelial downgrowth and give the bone and periodontal ligament time to regrow and establish. This is known as guided tissue regeneration.

Oral home care is a large part of maintaining periodontal health and treatment of periodontal disease.

The gold standard for oral home care is daily or every other day tooth brushing, which has been shown to significantly reduce the levels of plaque and calculus compared to over longer intervals (Harvey et al, 2015). Tooth brushing should be started at a young age, when the dogs are more amenable.

The building blocks of oral home care are positive reinforcement and a regular routine. I would advise clients to focus on examining the whole of their pet’s mouth and associating this with something positive, such as a treat or playing with the dog’s favourite toy, before progressing tooth brushing. Good visualisation of all of the oral cavity, as well as a compliant pet, is key to performing an effective level of oral home care.

Once the pet is happy with an oral examination, the client can then move on to using a finger brush or swab on the teeth. A finger brush is a good step towards brushing, but is not as effective because it cannot reach the subgingival plaque. When the client has finally reached the point where tooth brushing is tolerated, inform the client to angle the brush towards the gingiva to help with clearing of subgingival plaque.

The owners should be made aware that progression to using a brush may take months and the dog may require professional dental cleaning during that time. Multiple types of toothbrushes are on the market, but make sure that the brush is soft; I recommend a smaller brush, such as a child’s toothbrush, as it is easier to use. An electric toothbrush would be the best choice, but most dogs do not tolerate this.

We are more concerned with the brushing technique rather than the type of toothpaste in most cases of routine oral home care, and the paste is used as a lubricant for the bristles. Veterinary brands are a good option, but any store brand or food substance, such as pet-safe peanut butter, can be used.

Multiple add-on dental care products are available, such as water and food additives (Gawor et al, 2018), which have been shown to slow the level of plaque accumulation, as well as a range of dental treats and diets. I would always recommend using these alongside tooth brushing and not as an alternative.

For more information about approved dental treats, I recommend visiting the Veterinary Oral Health Council website via https://vohc.org