12 Nov 2021

Martha Cannon – in the final of her two-part article – addresses the issue of under-treatment regarding this common condition in cats.

Figure 7. Ellie has regained behaviours such as grooming and rolling in the sun, which she had stopped doing due to the level of chronic pain she was suffering.

Arthritis is a very common problem in cats that often goes unrecognised – and even when recognised, often goes untreated. A number of factors contribute to the under-diagnosis of this chronic painful condition and a clinically expedient approach to diagnosis was discussed in the first article in this series.

This second article addresses the problem of under-treatment, as even when owners or vets recognise that arthritis is present, barriers exist to providing long-term pain management. Finding ways to overcome these barriers is important; successfully managing the pain of arthritis can make an enormous difference to the cat (see the case example further on), and can be very rewarding for owners and veterinary staff.

Because the signs of arthritis are so subtle, the extent to which a cat has been affected is often only apparent when joint pain is treated effectively – owners often comment that their cat “has a new lease of life”.

It appears that around 60% of cats aged 6 years and older – and around 90% of cats older than 12 years of age – are affected by OA (Slingerland et al, 2011; Hardie et al, 2002), but the number of cats that receive treatment for this painful problem is significantly less.

A recent survey of vets in the UK suggests that even when OA is diagnosed only around 60% of affected cats are started on treatment (Zoetis Anti-NGF Veterinarian Quantitative Market Research, 2018).

This low treatment rate arises both because owners do not take up their vet’s treatment recommendation, but also in many cases because vets do not make a recommendation to treat. Factors that contribute to this high level of under-treatment include:

The latter two factors are not only a barrier to starting treatment, but can also be a significant factor in low long-term compliance – a recent survey of cat owners indicated that around 50% of owners who start treatment do not continue to administer the treatment in the long term (Zoetis Pet Owner Feline Journey Market Research, 2020).

Common reasons cited for stopping treatment included:

Many potential treatment options for management of chronic arthritis exist, ranging from prescription drugs through to nutraceuticals. Relatively few prescription drugs are licensed for use in cats, but some products licensed for use in dogs can be used off‑licence in cats in some circumstances and with owner-informed consent.

As always, care must be taken to use appropriate drugs at appropriate doses, and the optimum treatment plan will vary from cat to cat. Often, using a combination of different treatments provides a more balanced effect and allows individual drug doses to be kept relatively low.

Simple changes to the cat’s environment also have a big role in treatment – an indoor litter tray; a low-sided uncovered litter tray for easier access; steps up to the cat flap; and boxes, steps (Figure 1) or ramps will all allow the cat to access key resting areas and resources without pain.

Available medical treatments include the following.

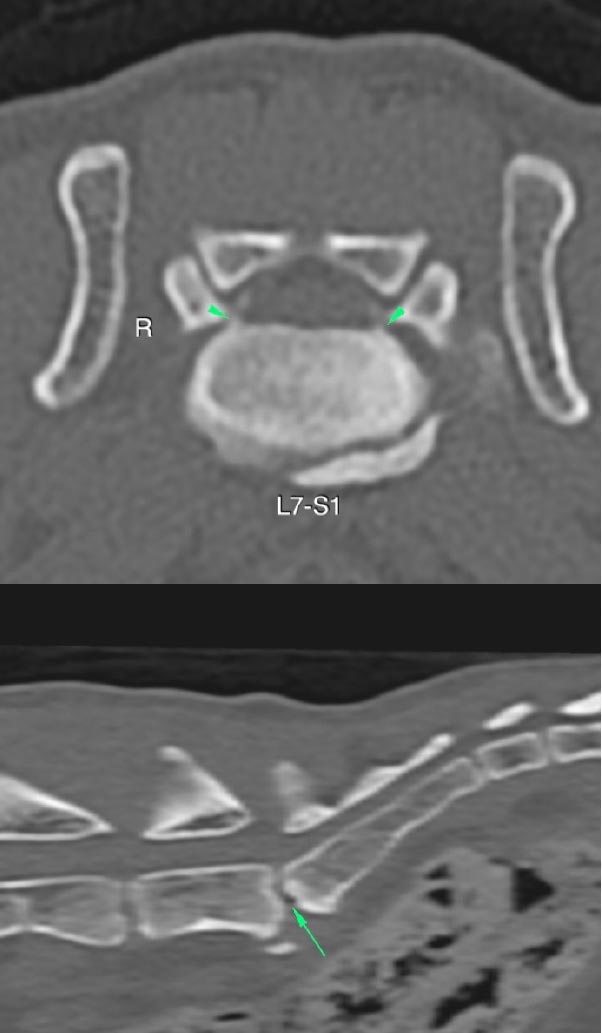

Ellie is a 10-year-old Siamese cat. She has multi‑joint OA and lumbosacral spondylosis (Figure 2). Eight months ago she developed severe back pain due to lumbosacral intervertebral disc disease with bilateral narrowing of the intervertebral foramina (Figure 3).

She underwent dorsal laminectomy and partial facetectomy to relieve the resulting dorsal nerve root compression. The surgery improved her lumbosacral pain, but in subsequent months her hip pain worsened and she started to exhibit elbow pain, with forelimb lameness and reluctance to bear weight on her left forelimb even at rest (Figures 4 and 5).

She was becoming aggressive when handled, disliked being stroked around her hind end and had withdrawn from family life due to the level of chronic pain she was suffering.

Ellie is a spirited cat who refuses to accept oral medications – she is owned by a very experienced and skilled feline veterinary nurse with years of experience in dosing cats, but even so daily delivery of any oral medications had proved impossible. Other non-oral treatment options were required for Ellie, and options included anti-nerve growth factor monoclonal antibodies, nutraceuticals, pentosan polysulphate injections, transdermal tramadol, Hill’s j/d diet and so on.

Ellie’s owner was keen to explore the effect of the frunevetmab (Solensia, Zoetis) as the prospect of providing pain relief via a once a month SC injection was very appealing.

Within six days of her first treatment, Ellie’s owners noticed a marked improvement; she was more mobile, with no appreciable forelimb lameness (Figure 6).

To date, the improvement has been maintained; she is a much happier cat, and is integrating with the family again and regaining behaviours she had lost, such as rolling in the sun (see Figure 7).

Ellie’s case illustrates the difficulties that even the most dedicated of owners can face when trying to treat a cat that does not want to be treated, but by adopting an open-minded approach to the wide range of treatment modalities available, a treatment plan can usually be found to suit all owners and their cats.

Around 90% of cats older than 12 years of age are affected by OA.

When OA is diagnosed, only around 60% of affected cats are started on treatment.

Around 50% of owners who start their cat on treatment for arthritis are unable or unwilling to continue it in the long term, often due to difficulty of dosing and frequent experience of adverse effects.