4 Nov 2025

Sophie Evans VNCert(ECC), FNCertISFM, RVN discusses initial stages of dealing with spinal patients, including assessment, diagnosis and treatment, as well as techniques for nursing them back to full health afterwards.

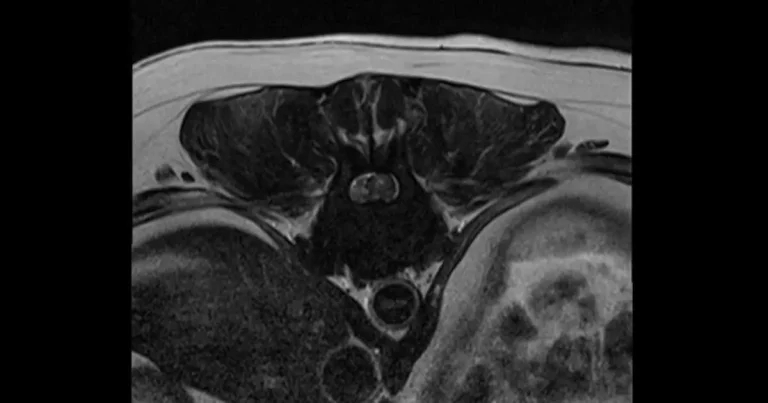

Figure 1. Transverse view of thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion (type I; disc material can be seen as a crescent shaped compression on the left).

Nursing the spinal patient can be intensive, yet rewarding, with cases that can have a varied prognosis.

The implementation of tailored care plans can vastly improve and aid recovery periods and quality of life. This patient type requires a large amount of nursing time and knowledge – with the addition of detailed owner education and emotional support.

The following article covers each aspect of care from patients arriving at the clinic. We must ensure a collaborative and consented approach alongside our clinicians and owners.

The vertebral column is a central support within the body that protects the spinal cord. Its purpose is to allow flexibility, movement, and to house and protect the spinal cord and nervous system.

The group sections of vertebrae from the neck to tail include:

Each vertebra is made up of a vertebral body and arch, with three processes (spinous, transverse and articular). Between each vertebra lies an intervertebral disc, which is a fibrous material with a gel-like fluid within. The function of the disc is to absorb forces and allow flexibility.

Chondrodystrophic dog breeds, such as dachshunds, shih-tzus and beagles, are seen to be at higher risk of premature disc degeneration due to a genetic mutation affecting cartilage and bone development (Carver, 2016). This mutation can cause chondroid metaplasia due to the alteration of disc fluid quality, resulting in higher risk of extrusion.

Ensuring that examinations and observations are described with correct terminology is important to detailed reports and case referrals. With spinal patients, it is crucial to report specific function or responses (Elphee, 2011; Carver, 2016). These are:

Patients may present with acute/emergency symptoms or chronic concerns. Both will require a full health and neurological assessment, which will aim to localise cause, deficits and assess current functions.

Assessment should include:

The Modified Frankel scoring system can be used to gauge the severity of condition and determine urgency and prognosis in interventions for suspected disc diseases. Its grades are:

Different variations of imaging modalities may be used in aim to determine the cause of presenting symptoms.

This is where a contrast medium is placed into the spinal canal to gauge movement through taking a radiograph series, with an aim to identify disc compressions where contrast is unable to pass.

This imaging technique is not frequently used, doesn’t identify the type of material and carries significant risks, but can be a useful tool in clinics without CT or MRI modalities (Prager and Granger, 2024; Robertson, 2011).

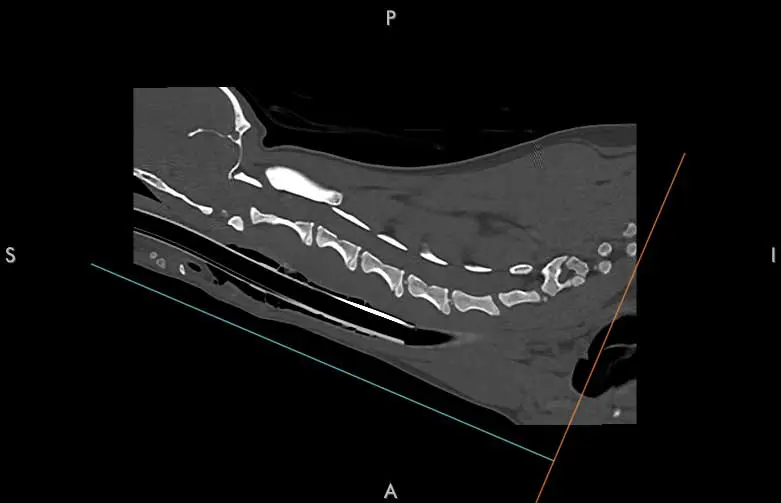

This is most frequently used in emergency situations or if MRI is not available. Benefits include allowing the ability to create a quick 3D image reconstruction and providing good detail on bones, fractures and neoplasia, but it may not be able to pick up the finer detail of the inside of the spinal cord or nerves (Prager and Granger, 2024).

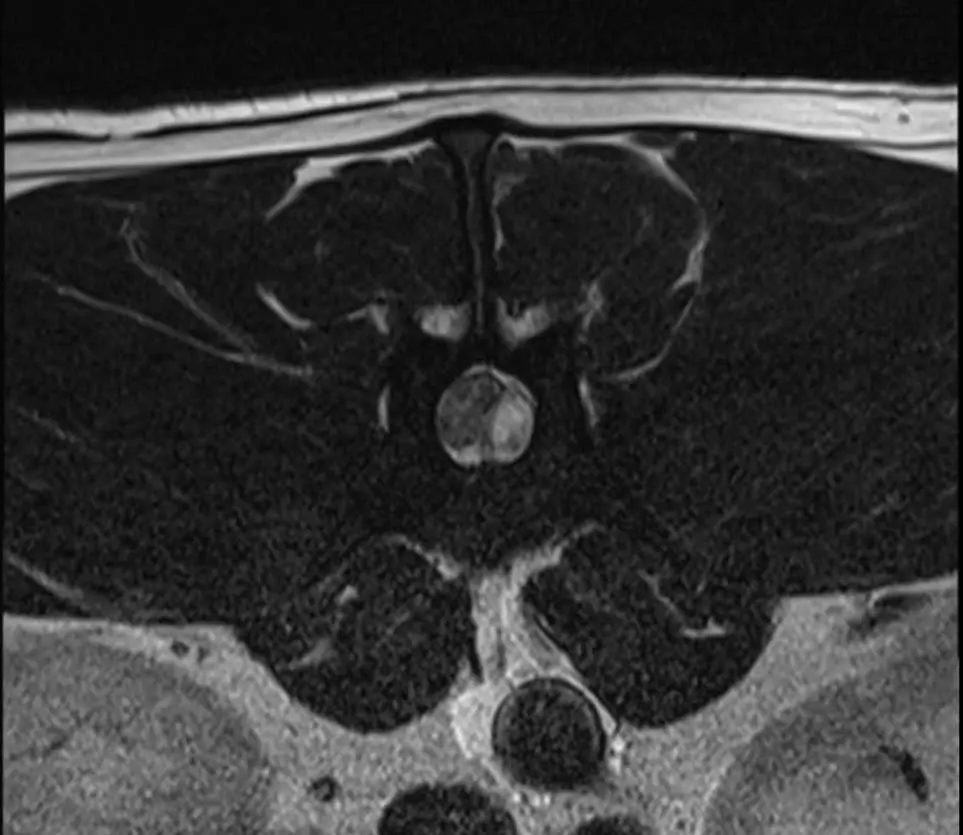

MRI is the most detailed form of imaging for spinal anatomy (Cooper et al, 2014). This modality can identify disc material, nerves, muscle, signs of haemorrhage and gives good soft tissue differentiation using different sequences (Dennis, 2011). It is seen as gold standard imaging, but duration of scanning time can be considerably longer in emergency situations and not all clinics have an on-site scanner.

The most common spinal condition (Holzman, 2023) is intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) – the herniation of the disc material that causes compression of the spinal cord leading to pain, weakness and paralysis (Dorn, 2022). It is the most common spinal condition.

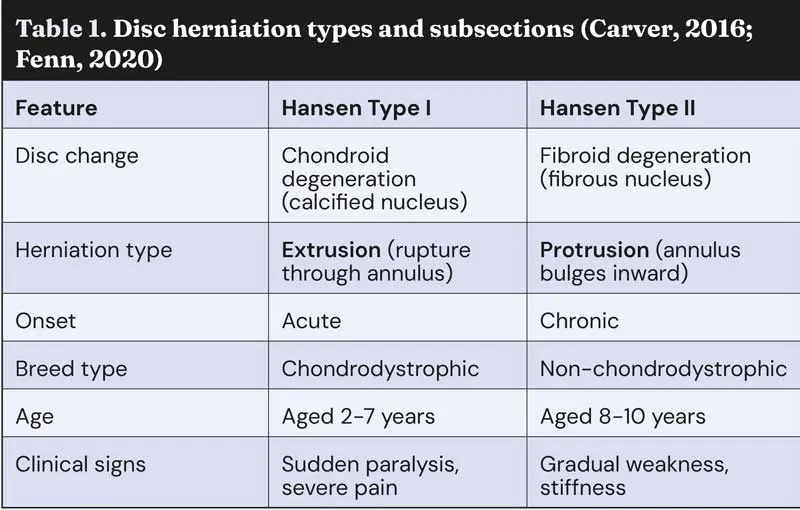

Different disc herniation types can be classified into two subsections (Carver, 2016, Fenn 2020), as seen in Table 1.

Surgical interventions may proceed following imaging of the spine. Haemilaminectomy is the most common type of spinal surgery to treat IVDD. This procedure will remove a section of vertebrae lamina and articulae facet to allow for access to the vertebral canal to remove extruded disc material and decompress the spinal cord (Platt, 2013).

This is most performed in the thoracolumbar region. Prognosis is best in patients with Modifed Frankel scoring of 2 to 4 prior to surgery or 5 less than 48 hours prior to onset of symptoms.

We often hear the term “slipped disc” when discussing IVDD. It is important to recognise that the cause of pain and neurological changes is due to protrusion or extrusion of the disc material from the disc space, rather than movement of the disc itself.

Fibrocartilaginous embolism (FCE) – a fragment of cartilage can break away and block blood vessels causing an embolism, resulting in an ischaemic event.

Usually, acute events but often are localised and non-painful (Cohen, 2025). These cases swiftly recover with supportive care.

Injuries or traumatic events causing fractures, dislocations or luxations can lead to spinal instability, with secondary risk of swelling or haemorrhage following acute trauma (Thomas, 2024).

Surgical spinal fixation or reductions may be indicated in these patients or strict rest may be considered.

It is important to ensure that management of any other trauma-related presentations are treated concurrently.

Discospondylitis is an infection of intervertebral disc and adjacent vertebral end-plates caused by haematogenous infection, trauma or migrating foreign bodies (van Hoof et al, 2023).

Decompression surgery may be indicated following imaging, or medical management of a culture-driven antibiotic course, pain relief and rehabilitation of any dysfunctions.

Presenting conditions are often spinal hyperaesthesia, lethargy and chronic signs of reduced mobility, alongside unremarkable blood tests (Gomes et al, 2022).

Similar to FCE, acute non-compressive nucleus pulposus extrusion (ANNPE) is essentially a disc extrusion that does not need surgery.

It can present with acute pain, plegia or paresis, often asymmetrically, following a high energy activity or trauma. It is most common in young and active medium-to-large breed dogs.

At each stage, the risks and prognosis must be discussed in detail with owners, which also includes financial information for current and ongoing care.

Patients with spinal conditions can often be time-consuming and physically demanding for owners to care for. A patient’s temperament will be a consideration, as would how well they would suit rehabilitation periods and physiotherapy.

Plenty of disability aids are now readily available for dogs and cats. If owners are open and committed to caring for a disabled pet, they can live a fulfilled life, with supports such as wheels and braces.

We will now discuss implementation and considerations of how to nurse the patient following on from diagnosis and treatment.

Kennels should be spacious enough to allow for essentials such as food, water and resting space, but not so large that over-exertion can occur. Bumper blankets should be inserted around the diameter of the kennel to give neck support (Dorn, 2022).

Raised bowls should be placed to reduce bending and overstretching of the neck. Bedding should be soft and absorbent to any waste products; incontinence sheets can be inserted under the patient, but must be removed as soon as soiled.

Top tip: for longer stay patients, a quiet, traffic-free kennel will be beneficial to allow undisturbed rest.

Patients must be placed in alternate recumbency every four hours. When turning patients, it may require multiple people to ensure no strain or twisting of the spine occurs.

Any signs of pressure sores or ulcer formation should be checked at each turn. These can occur due to prolonged pressure to areas, particularly bony prominences, which reduces blood flow to skin and additionally away from the pulmonary systems, also leading to a risk of secondary hypostatic pneumonia (Elphee, 2011).

A rolled-up blanket could be placed between legs to reduce sweat rashes. Hospital sheets should be clearly marked when patients are turned to ensure they aren’t left in the same recumbency for extended periods of time.

Top tip: apply barrier creams pre-emptively to patients that are at risk of scalds or skin irritations – especially un-neutered males.

Patients’ vitals should be taken throughout the day to ensure that any abnormalities are identified. Some neurological conditions can affect how the patient thermoregulates (Elphee, 2011). It is crucially important to advocate for patient rest during hospital stays and consider hands-off monitoring for periods to allow sleep.

Commonly, the bladder will be affected in spinal conditions; this can lead to incontinence or retention of urine. Management of leakage may indicate placing an indwelling urinary catheter to reduce risk of urinary scalds and ability to measure output, but it should be managed aseptically to avoid ascending urine infections (Smarick et al, 2004).

Ensuring the urinary catheter is correctly cared for once inserted is key. Cleaning and inspection of the line should be performed every four hours, as well as correct storage on the collection bag outside of the kennel (Bloor, 2018). If no catheter is present, urine retention may be managed by monitoring the bladder size every four hours and bladder expression as needed.

Palpation can be performed manually and, for more precision, an ultrasound can be used to give an approximate volume. Medication to relax the urethral sphincter can be used to aid expression and promote normal urination (Thompson, 2009). Faecal incontinence can occur; the patient must be kept clean and supported for eliminations when possible. An enema may be indicated in some cases.

Ensuring patients are comfortable during their stay is essential for their welfare. We must critically and frequently assess patients for signs of pain. Pain scoring systems such as the Glasgow Composite Pain Scale for dogs and cats can be used. Canine versions of this scale should not include the ambulatory section, to allow comparable results out of 20. Analgesia interventions, plus suitable de-escalations, should be undertaken (on condition of pain score) to ensure patients are comfortable, but not having negative side effects from excessive pain relief.

Top tip: is every nurse pain scoring the same? Hold an in-house CPD on pain scoring systems and assess together.

Calculating the patient’s resting energy requirements (RER) for their weight and matching their intake is gold standard nursing care. Tempting with a range of foods and hand feeding may be needed during their stay.

Periods of withholding food for general anaesthetics may take place, but patients should not be fed large amounts after an anaesthetic, so RER on these days may be reduced.

Intravenous fluid therapy may be given alongside nutrition to maintain hydration until the patient is eating their full RER.

RER calculation: 70 × (BW kg)0.75 (adjusted accordingly for age)

Pre-existing conditions should be considered as they can influence care, such as patients with chronic arthritis or breeds prone to regurgitation. This may highlight the need for additional mobility support, altered kennelling set-up or additional medications to care plans.

Postoperative wound care should be incorporated, including dressings, buster collars or medical pet shirts, if required. Often they may not be able to reach the surgical site, but they must be monitored closely (Holzman, 2023).

Signs of surgical postoperative complications, such as haematomas, surgical site infections, dural tears and progressive myelomalacia, should be monitored and considered if any patient is not progressing as expected (Golini, 2018).

Static active warming, such as through use of warming blankets, should be used with great caution. This is due to a patient’s ambulatory status resulting in them not being able to move away from the blanket and the risk of burns if they become wet with urine.

Patients may spend a varied time period within the hospital during their recovery. Ensuring that they are mentally stimulated aims to reduce boredom and negative behaviours that may accompany the period in the hospital. Implementing a low stress environment and using free-fear handling techniques should be undertaken.

Due to the nature of possible surgery and recovery, the enrichment types would need to be calming and static. Perioperative emotional distress can significantly heighten pain levels and reduce tolerance overall, encouraging the need for a positive hospital experience (Lazard et al, 2024).

Owner visits have also been shown to improve the comfort and emotional enrichment with a positive effect on recovery (Lazard et al, 2024).

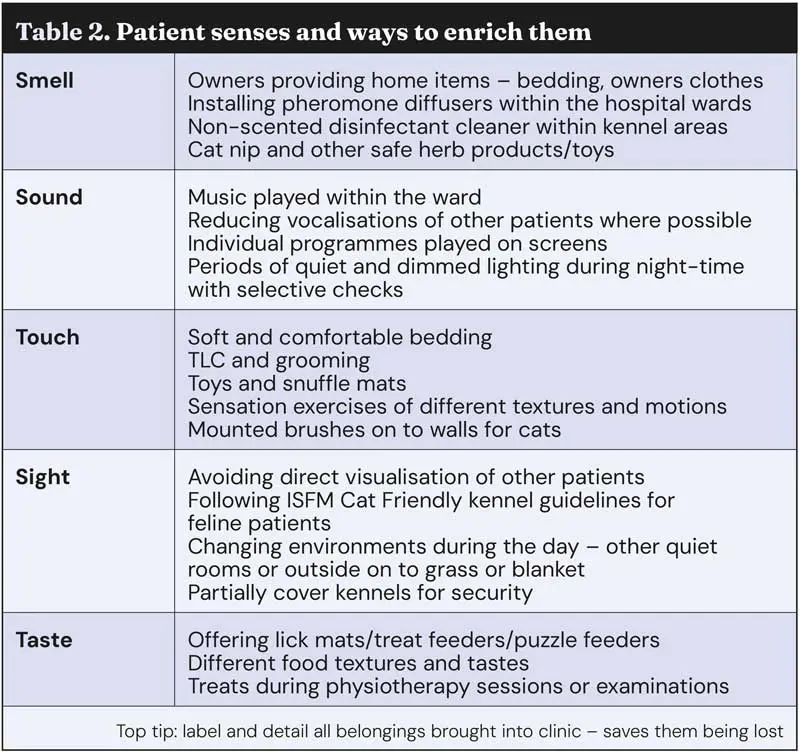

Enrichment should aim to meet all senses of the patient to provide variety and a comprehensive care plan (Table 2). Owner involvement in these plans can be key to targeting a patient’s individual needs by selecting enrichment activities they usually enjoy. Be proactive alongside clinicians to undertake nursing intervention telephone calls or discussions with owners – they can be simple questions such as how they enrich their pets at home, or the types of food they like, but the answers can significantly modify and improve hospitalisation plans.

These enrichment tools can be adapted outside of the clinic to maintain owner-pet bonding following discharge, as patients may not be able to undertake their usual activities, such as walking or training classes.

Rehabilitation periods in spinal patients can be prolonged, so ensuring enrichment within the home can have similar positive effects.

A study showed that up to 78.5% of dogs showed stress or fear when entering the veterinary clinic (Edwards et al, 2019). This can be intensified by the hospital environment, stress or pain. The veterinary team should be able to clearly identify behaviour and body language that may indicate fear or stress. Signs can be aggression, panting, pacing, crouching, hiding, lip-licking and avoidance of touch (Grigg et al, 2022). Handling techniques to reduce fear are important. The following should be borne in mind:

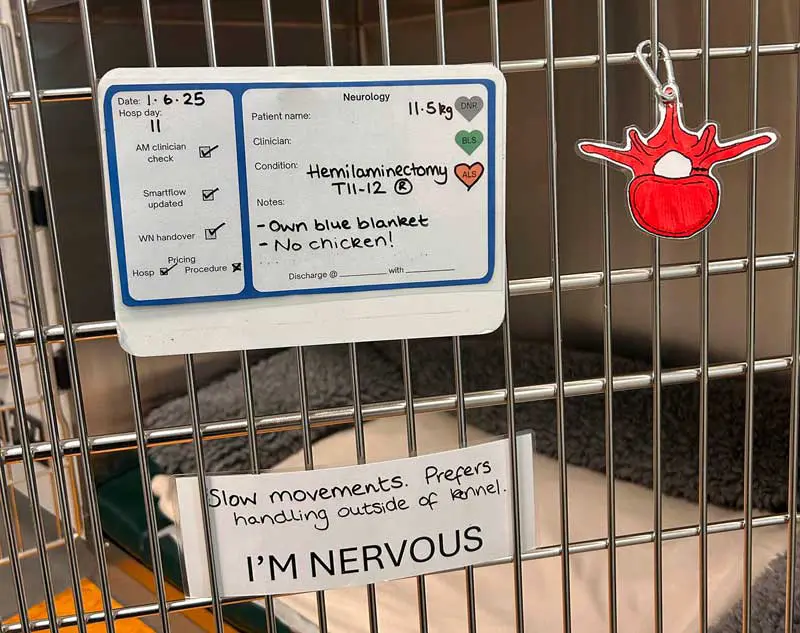

Top tip: ensuring kennels are labelled with behaviour notes is important for safe handling.

Physiotherapy is a crucial part of recovery care for some spinal patients, which can be undertaken by nurses following clinician instruction.

It is important to understand that prior to imaging, diagnosis or immediately after surgery, physiotherapy should not be performed if any suspicion exists of spinal instability or isn’t indicated at that stage. Great care must be taken to support the spine and prevent any unnecessary manipulation or contortion during any exercise (Dorn, 2022).

These treatments will aim to retain mobility, improve and maintain muscle strength, aid co-ordination and provide lymphatic drainage (Henea et al, 2023). Passive range of motion and massage are the most indicated physiotherapy techniques. Treats and encouragement should be used to positively reinforce these activities.

Setting up a quiet space with non-slip floor and comfortable bedding will be needed. An exercise ball and balance board may also be used in later stages of physiotherapy for some patients (Carver, 2016).

Intensity and frequency will be determined by the patient’s presenting mobility and condition. Establishing a set range of exercises within clinic and displaying these with a visual aid on to the patient’s kennel can be useful. Colours will indicate activities instructed to be undertaken, which avoids any incorrect exercises being performed on patients.

Elements to be borne in mind include the following:

Details of physiotherapy treatments can be found from a number of sources (Carver, 2016; Dorn, 2022.

Position: each lateral recumbency, each limb in turn.

Goal: increase lymphatic drainage to remove toxins and increase blood flow to muscles.

Considerations: massage towards the heart and not towards the paws.

Limbs

Body

Top tip: In IVDD patients remember to include the cervical muscles due to the low head carriage posture.

Position: each lateral recumbency, each limb in turn.

Goal: to decrease pain, reduce oedema and reduce joint degeneration.

Considerations: performing these exercises in low pain threshold patients or those with severe tissue trauma may need to be undertaken with more caution. Can be undertaken from 1 to 12 hours postsurgery, but as advised by the clinician. No movement should be forced.

Position: supported standing with a straight spine.

Goal: strengthens muscles and improves proprioception.

Considerations: always be in close contact and ready to catch the patient. A non-slip surface is key for this exercise. A peanut ball can be used in larger dogs to give extra support.

Position: supported standing with a straight spine.

Goal: limit muscle atrophy during reduced mobility.

Considerations: usually started two to three days after surgery.

Sensation exercises can be incorporated in an aim to stimulate the nerve endings; this can be toe tickles, tapping, warm or cold packs, vibrations to paws or body and different motions of stroking.

When walking patients, they should be adequately supported to their ability.

A suitably fitted harness should be placed to encourage correct spine position, pressure and weight distribution. This should be done three to four times daily, if indicated (Dorn, 2022).

Ambulatory patients should be walked with a harness and top attaching lead, alongside a belly band to support if they become ataxic and weak during walks.

Non-ambulatory patients should be treated the same as with ambulatory patients, but with the hindlimbs supported higher than the ground to stop dragging; you can also lightly touch the ground on soft surfaces to stimulate toes.

Local physiotherapists may be recommended for owners outside of the clinic to aim for a collaborative approach to recovery and provide support to the patient and owner following discharge. Other treatments may be available, such as laser therapy, acupuncture or hydrotherapy, but this must be authorised by the clinician first.

Owner education will be an important stage in a patient’s recovery journey (Smith, 2018). Support and guidance will be crucial for the best outcome for the patients and their owners. Hand-out information and pre-discharge reading can be ideal as to not overwhelm carers at discharge and allow them to appropriately prepare themselves and the environment at home.

Appointment times should be carefully considered as to not rush demonstrations or overlook owners’ questions. Support devices may need to be ordered or prepared, such as ramps, wheels, beds and harnesses, so ensure this is discussed as early as possible to allow the owners time to prepare appropriately.

Setting small and achievable goals can allow positivity in cases of prolonged recovery. It is important to understand this can be an emotionally distressing period for some owners, and they may need extra support and compassion during this time (Smith, 2018). It is also essential owners can recognise signs of deterioration and understand when to contact the practice, as delaying until a scheduled revisit may result in critical consequences. Progression diaries can be a good way of documenting the patient’s convalescence period.

The nursing of a spinal patient can be complex and time consuming, yet very rewarding. As RVNs, we can take pride in collaboratively working with our clinicians to provide excellent nursing care to patients and supporting owners.

The author thanks colleagues at Blaise Referrals – April, Emma, Georgia and the neurology team.