14 Apr 2020

Itchy cats and dogs: causes of irritants and cures

John Redbond details how pruritus commonly manifests in companion animals, and how to identify and treat its origins.

Image © Reddogs / Adobe Stock

Skin problems account for the majority of cases coming through the door of a first opinion practice, with 32% of dogs and 27% of cats presenting with dermatological disease of some kind (Nielson, 2014).

Particularly for dogs, itchiness – or pruritus – is the most common clinical sign (Hill et al, 2006) and can have a big impact on patients’ quality of life, as well as having the pet owners metaphorically pulling their own hair out in frustration. Ascertaining what is causing it requires some understanding of the likely reasons – this article looks to explore the more prevalent issues.

Bacterial skin infection

Bacterial overgrowth or infection on the skin should always be considered as, in the author’s experience, this is a very common factor in pruritus.

More common in dogs than in cats, it occurs generally as a result of an underlying cause, but will exacerbate symptoms to a level that drives owners to come to the practice for a resolution. Bacteria is present (commensal) on the skin naturally, but the patient scratching and rubbing causes the levels to increase – in turn increasing symptoms.

This could simply be a bacterial overgrowth or colonisation, without being classified as an infection, in which case non-prescription topical antimicrobial treatment – such as shampoos, foams and sprays – should be enough to resolve the issue. These can be chosen according to an owner’s capabilities and the presentation, with skin folds benefiting from regular use of wipes, for example.

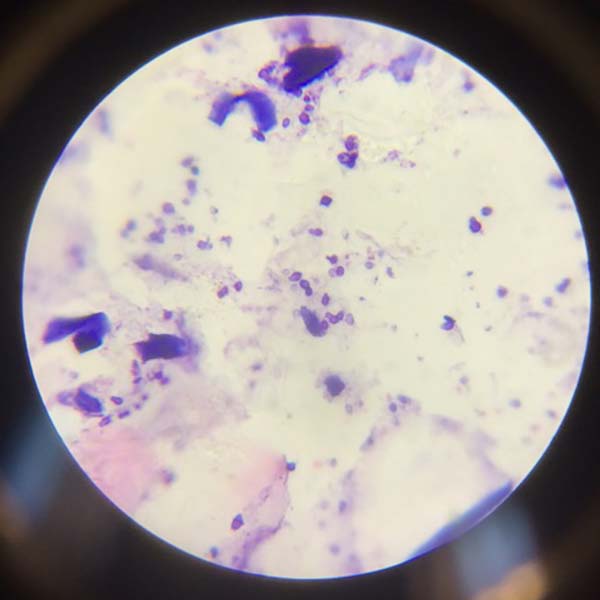

The presence of excess bacteria is ascertained by performing cytology – an often overlooked and under-performed test – including tape strips and impression smears, which are simple and quick for a VN to perform to detect the presence of microbes on the skin.

This is also the method for deciding if this is simply an overgrowth or – if cytology shows the involvement of inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, as well as bacteria – an infection. This is then identified as either superficial pyoderma, where the surface of the skin – such as the hair follicle or area around it – has become affected; or, in some severe cases, deep pyoderma, which involves the whole hair follicle down to the dermis and, in some cases, the subcutis.

Treatment always involves the use of topical therapy. As the issue needs resolving on the surface, the vet may then select systemic antibiotics for more severe cases, such as deep pyoderma, or in superficial pyoderma cases that have not responded to topical treatment alone.

Performing cytology to identify bacterial issues and repeating to assess response to treatment is key to success, and this is where the VN is essential in taking samples, staining them, and, with practice, identifying cells under the microscope.

Malassezia dermatitis

With many predisposed breeds, Malassezia – a commensal yeast that loves warm, moist places, such as skin folds, interdigital areas and axillae – can often be found to be either causing – or, in many cases, exacerbating – symptoms.

Known for its classic peanut or footprint shape, it is, like bacteria, seen on skin cytology at a high magnification (×100 oil). This can be a cause of pruritus and, while not necessarily in all cases, is common to find so is worth identifying and removing with topical therapy.

Otitis externa

Otitis externa is often a cause of pruritus; regularly encountered as it occurs in 10% to 20% of dogs and 2% to 6% of cats (Angus, 2004; Saridomichelakis et al, 2007).

Sometimes, in our minds, we separate ear disease from skin disease; however, the inside of the ear is also the surface of the skin, so a direct link nearly always exists between issues over the coat generally and issues down the ear. So, when facing a pruritic patient, examining the ear if not taking cytology has value.

In almost every case, the ear disease will be as a result of an underlying issue, such as allergy or other skin disease. The patient may well be predisposed by its confirmation, such as a long pinna – and, indeed, over time, change such as inflammation can perpetuate the issue and make management more difficult for the owner. But the key to management is to look to identify the underlying primary cause, while managing secondary infection found in cytology, such as bacteria and yeast as discussed.

As with the aforementioned skin cytology, this is very simple, performed with a cotton bud rolled just inside the ear canal and, again, on to a slide before staining and examination under high power (×100 oil). Correct identification of level and type of microbes present can help selection of an appropriate ear cleaner, which alone will often resolve the case without the need for prescription antibiotic or antifungal drops. However, it may be necessary to help the client with this process to aid compliance and increase the chance of success.

Parasitic infestations

It is important to always consider the possibility of parasites – particularly fleas – in causing pruritus in patients. A number of creatures can cause this, including Cheyletiella (mites), Otodectes cynotis (ear mites), Neotrombicula autumnalis (harvest mites) or different lice, among others. However, the three most prevalent, in the author’s experience – and how to find them – will be discussed in this article.

Fleas

The majority of cat skin issues can be attributed to fleas and, if not, most certainly exacerbated. As such, it is crucial to ensure they have been ruled out – particularly in cats, but also in dogs.

This can be done with a simple coat brushing, where the coat is combed and stroked, and the skin cells and material mounted on to a piece of sticky tape and on to a slide to look for microscopic flea dirt (red flecks on ×10 objective).

The familiar wet paper flea test – and even a simple flea comb – can be used, but these are not as sensitive to revealing the presence of fleas, which can cause issues even in very low numbers – particularly in cases of flea allergy dermatitis (FAD), often seen in cats. Owners can be hard to convince on the presence of fleas, due to the stigma attached and the fact you will often not see a live flea, so this test is invaluable in helping compliance.

Demodex

Due to the efficacy of latest flea prevention treatments on Demodex, this commensal mite is not considered in cases as much as it used to, which can mean it gets missed. Presenting as juvenile onset (generally, below 18 months old) or in older immunocompromised patients, this can be pruritic or non-pruritic, but generally causes erythema and alopecia to varying degrees.

Hair plucks are a simple and effective way to identify the mite, as it resides in the follicle of the hair, with the mite having a distinctive cigar shape. Treatment is more easily found in recent times, with flea prevention options that treat Demodex now available; in some severe cases, using amitraz dip may be necessary.

Scabies

While not common – about 1% of skin conditions in dogs (Hill et al, 2006) and rare in cats – scabies gets its name from the Latin scabere, which means to scratch, and cases are incredibly pruritic and worth considering when presented with pruritus. It is caused by Sarcoptes scabiei var canis in dogs, with feline scabies being what notoedric mange is known as – caused by Notoedres cati.

The method for diagnosis is by skin scrapes, by scraping cells from the epidermis with a scalpel and mounting on to a slide for analysis; multiple scrapes need to be taken to have a still limited chance to find the mite.

Often, the pruritic nature of the patient and the clinical signs of peripheral lesions are enough for a vet to suggest treatment. This, in severe cases, again may be amitraz baths; however, a number of flea treatments are now available with efficacy against Sarcoptes.

Allergy

Allergic skin disease is a very common skin disease seen in practice and the most common sign for this is pruritus. However, it cannot be assumed that pruritus means the patient is allergic, because, as we have seen in this article, many other potential causes exist. To diagnose this, the differential diagnoses of other itchy conditions must be ruled out by performing the cytology tests, hair plucks and skin scrapes as aforementioned – along with a thorough history.

This makes diagnosis difficult and frustrating for owner, vet and patient alike. The three main types of allergy are to FAD, which is an allergy to flea saliva; atopic dermatitis (AD), which is an allergy to something in the environment; and adverse cutaneous food reaction (ACFR), which, while not strictly an allergy, is generally referred to as a food allergy.

These are all diagnosed by the exclusion of other causes. In addition, FAD is aided with tests such as the aforementioned coat brushings and serology to identify sensitivity; ACFR by performing a food trial; and AD by additionally ruling out these other two allergies, as well as other causes.

It is important to note serology alone does not diagnose allergy, as an asymptomatic patient could test positive to sensitivity and, equally, a positive symptomatic patient could be symptomatic for another reason.

Treatment for these are, in the case of FAD, through flea control, for ACFR dietary control and, in the case of AD, potentially immunotherapy and/or long-term anti-pruritic systemic medication. All allergies generally require a multimodal approach to treatment, which is likely lifelong, and all benefit from topical therapy – either as the sole treatment, or alongside other therapies, to reduce the patient’s itch threshold and manage the condition.

Conclusion

Many potential causes for pruritus exist; even when identifying the most prevalent, this still leaves many possibilities.

Without doubt, the key is approaching the patient properly, with the necessary tests, gathering of history and clinical information to give the best chance of identifying the cause; rather than using educated guesswork to select treatment and risk a lack of long-term resolution, causing the patient prolonged discomfort and the owner great frustration.

The VN plays a vital role in this process, allowing a time-constrained vet to perform the tests necessary; a VN is permitted and completely capable of doing this, as well as analysing the samples under the microscope to report back to the vet. Topical therapy is vital in management of long-term pruritic skin disease.

Again, the use of the VN to select appropriate non-prescription topical therapy – as well as educating and supporting clients in the correct use of these, and prescription therapy – is of enormous benefit to compliance and, ultimately, the chance of a positive patient outcome.

References

- Angus JC (2004). Otic cytology in health and disease, Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 34(2): 411-424.

- Bannoehr J (2019). Companion animal dermatology, Vet Times 49(37): 6-8.

- Blacklock B (2012). Approaches to scabies in dogs, Vet Times 42(37): 16-17.

- De Bellis F (2014). Latest thinking on atopic dermatitis in cats and dogs, Vet Times 44(14): 12-15.

- Hill PB et al (2006). Survey of the prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of dermatological conditions in small animals in general practice, Vet Rec 158(16): 533-539.

- Maginn K (2016). Management of otitis externa and the veterinary nurse’s role, Vet Nurse 7(1): 4-9.

- Malik R (2012). Cats, foxes and scabies: the epidemiological puzzle of sarcastic mange, Vet Rec 171(7): 346-347.

- Morrison G and Robinson V (2019). Itchy pet cats and dogs – scratching the condition’s surface, VN Times 19(4): 6-10.

- Nielsen TD et al (2014). Survey of the UK veterinary profession: common species and conditions nominated by veterinarians in practice, Vet Rec 174(13): 324.

- Neuber A (2018). Reviewing main varieties of canine allergic skin disease, Vet Times 48(43): 8-12.

- Paterson S (2013). Management and control of skin infections in companion animals, Vet Times 43(7): 8-10.

- Saridomichelakis MN et al (2007). Aetology of canine otitis externa: a retrospective study of 100 cases, Vet Dermatol 18(5): 341-347.

Meet the authors

John Redbond

Job Title