1 Aug 2019

Abi Charteris explains the vital role nurses can play in early detection and subsequent management of acute and chronic forms of this condition in companion animals.

Nurse-led clinics are an excellent way to support clients through the management of CKD. Image © Monkey Business / Adobe Stock

Chronic kidney disease affects an estimated 0.37% of dogs and 4% of cats in the UK (O’Neill et al, 2013; O’Neill et al, 2014), yet identification of the condition at an early stage remains difficult (Syme, 2016). A thorough knowledge of the symptoms and predisposing factors for renal dysfunction ensures veterinary nurses can provide a vital role in the early detection and subsequent management of all forms of renal disease.

Many of the symptoms may be so grateful in onset as to be unrecognised by the owner, and, in these cases, the ability to identify potential sufferers at routine nurse appointments (preoperative and postoperative, general health checks and geriatric clinics) may significantly improve prognosis for our patients.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is the most common kidney disease affecting dogs and cats. It is defined as kidney damage present for at least three months, with or without azotaemia, or more than a 50% reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) for more than three months (Forrester et al, 2010).

In acute kidney injury, or acute kidney disease (AKD), renal function declines rapidly over hours to days, and affected dogs and cats become acutely ill. Prompt diagnosis and treatment can often prevent or minimise permanent renal damage.

If affected renal tissue is not irreversibly damaged, patients maintained with supportive care may regain enough renal function through hypertrophy of remaining nephrons to sustain normal life. However, in many cases, some or all of the damage may be irreversible, and hence chronic kidney disease may result from an acute kidney injury (Senior, 2017).

Acute or chronic presentations may also be seen in veterinary patients – especially cats – when compensated CKD exhibits no clinical signs until an acute uraemic crisis is superimposed (Langston and Myott, 2011).

Several predisposing factors should be made aware of that may point to potential renal disease in patients.

Many forms of hereditary renal disease are breed specific – for example, polycystic kidney disease in Persian cats, hereditary nephritis in cocker spaniels or renal amyloidosis in Shar Peis. Juvenile onset of renal disease is more likely to occur where hereditary disease exists and we should be aware of this possibility when performing health checks on younger animals from breeds known to be affected (Roura, 2016).

Certain therapeutic drugs and toxins are also known to cause or predispose animals to renal disease. Ethylene glycol (cats and dogs), Lilium species (cats) and grape/raisin ingestion (dogs) have all been identified as nephrotoxic substances, as well as many others, and exposure to any one of these should warrant prompt further investigations (Eubig et al, 2005).

As well as toxic causes, we should also be aware of the possibility of renal disease developing or worsening in patients treated with many therapeutic drugs. NSAIDs are among the most common drugs used in veterinary practice and account for the highest number of reported adverse reactions. Renal issues are the second most common adverse events reported following NSAID administration (Lomas and Grauer, 2015).

Many practices run nurse-led geriatric clinics that provide a frequent point of contact for monitoring the renal function of patients on NSAIDs or other drugs that may affect the kidneys.

General anaesthesia is also a significant risk factor associated with the development or deterioration of renal disease. The kidneys receive 20% to 25% of cardiac output and have an oxygen consumption higher than that of the brain. General anaesthesia often decreases cardiac output and results in hypotension, with one report showing 22% of dogs and 33% of cats were hypotensive during elective procedures. Renal blood flow has a direct effect on GFR.

While in a healthy patient autoregulation means GFR can be maintained in the face of marked changes in systemic blood pressure (mean arterial pressure 80mmHg to 180mmHg), this is not the case if renal function is decreased (Robertson, 2015). We must, therefore, be especially aware of assessing for signs of renal disease in our patients before and after any surgical procedures.

A thorough history at admission is essential, and preoperative blood and urine testing should be recommended where possible to identify at-risk animals. The author has seen an apparently healthy eight-month-old dog present post-routine neutering with AKD, which was rapidly assessed and diagnosed by the vet as a result of a routine postoperative check.

Clinical symptoms for both AKD and CKD are very similar, though the speed of onset differs between the two. Sudden onset of symptoms indicates an acute process that requires urgent medical or surgical intervention to stop ongoing kidney injury. In contrast, CKD patients tend to present with a history of waxing and waning for several months with an associated weight loss (Langston and Myott, 2011).

In cases of CKD, the onset of clinical signs is often so gradual that owners may not recognise them until the disease is well established – limiting our ability to manage the disease successfully. It is important, then, that we are alert to any signs of renal disease, even in routine appointments, so we can intervene at the earliest possible point.

In one historical study, 1% of dogs presenting for vaccination in the UK were diagnosed with CKD (MacDougall et al, 1986). CKD is most frequently a disease of older pets. In one study, the mean ages of patients with kidney disease were 10.2 years in dogs and 13.2 years in cats (Hutchinson et al, 2018).

Symptoms can include, but are not limited to:

One retrospective study evaluated the frequency of clinical signs in cats with CKD and found vomiting was noted in 52% of cases, PUPD in 40% of cases, inappropriate urination in less than 10% and diarrhoea in only 3% of patients.

Another study looked at the recognition of clinical signs by owners before diagnosis of CKD and found PUPD was noted by the owners for 12 months in cats and 6 months in dogs before diagnosis, while halitosis was also recognised at home for a year prior to diagnosis.

Weight loss is another prominent sign, with studies showing a five-times greater decline in weight in CKD patients in the 6 to 12 months prior to diagnosis compared to unaffected animals (Hutchinson et al, 2018).

These studies highlight that, often, the signs of renal disease are present well before the diagnosis is made, and regular check-ups, careful history taking and recording of bodyweight at every appointment – especially for our geriatric patient – are extremely important in early identification of renal patients.

Once renal disease has been staged, it is important to repeat diagnostics at regular intervals to monitor progress. The exact interval for repeated testing will vary depending on each patient, but the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) recommends around every three to six months once a patient has stabilised (IRIS, 2017a; 2017b).

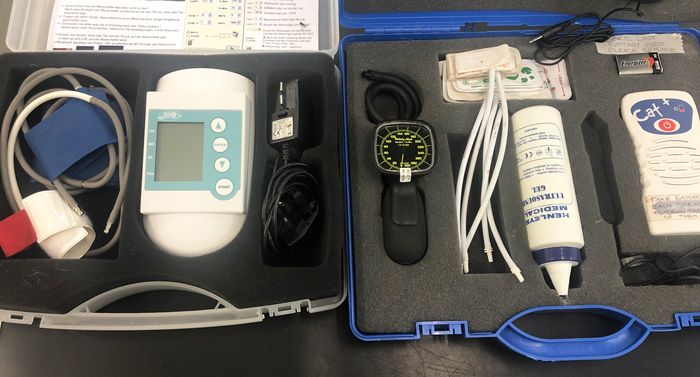

Repeated blood testing, urinalysis and blood pressure measurements are all within the scope of a geriatric nurse consult and, therefore, veterinary nurses have a key role to play in the overseeing of care after diagnosis. Nutritional management is also a mainstay of managing renal disease and should be an important part of every geriatric consult – especially if the patient has been diagnosed with renal disease.

Systemic hypertension is estimated to occur in around 66% of CKD patients (Grauer, 2008) and is of concern because a chronically sustained increase in blood pressure produces injury to the kidneys, eyes, brain and cardiovascular system.

The rationale for treating hypertension in dogs and cats is to minimise or prevent this injury to these organs (Brown, 2016). Hypertension is difficult to quantify accurately in a veterinary clinic where a patient’s blood pressure may be elevated as a result of anxiety and other factors. A standard protocol is important in obtaining the most accurate blood pressure values, such as the one provided in the following list:

IRIS provides guidelines for substaging CKD patients according to their risk of hypertensive injury, which take account of the stress our patients often feel when visiting the clinic (Table 1). Where moderate to high risk of hypertensive injury is identified, or in cases where hypertensive retinopathy or other hypertensive sequelae have already occurred, treatment with antihypertensive medications may be prescribed by the veterinary surgeon.

| Table 1. International Renal Interest Society sub-staging of blood pressure in dogs and cats based on risk for future target organ damage | ||

|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Blood pressure sub-stage | Risk of future target organ damage |

| <140 | Normotensive | Minimal |

| 140 to 159 | Prehypertensive | Low |

| 160 to 179 | Hypertensive | Moderate |

| ≥180 | Severely hypertensive | High |

| Adapted from Brown et al, 2007. | ||

Nutrition is the cornerstone of renal support and understanding dietary modifications required can improve not only life expectancy of the patients, but also the compliancy of owners using such diets. Many clinical studies have concluded the importance of nutritional management of CKD with the use of specially formulated diets being shown to improve quality of life by reducing clinical signs, but also extend survival times (Villaverde, 2009).

Despite popular belief, increased protein levels are required (especially in cats) to compensate for protein losses. This is also reflected in humans, where recommended protein intake is twice the normal value for maintenance (Morallion and Wolter, 1994). However, the type of protein should be carefully considered. A study using partially nephrectomised rats concluded high protein diets led to a destruction in surviving nephrons (Kenner et al, 1985).

Alternatively, feeding an inadequate amount of protein can also produce adverse effects, such as a loss in muscle mass and an increased protein catabolism, resulting in an elevation in accumulated nitrogen waste products. Due to the difficulties faced with the CKD cat’s protein requirements, it is advised a highly digestible protein is used. This allows an optimum amount of amino acids to reduce progressive disease, but maintain adequate nutrition.

Strong evidence exists to support the provision of phosphorus-restricted diets in animals with CKD (Korman and White, 2013), with serum phosphate levels used as an independent predictor of disease progression. It is suggested these diets can control serum phosphate levels (with 100% diet compliance) until up to stage III of the IRIS staging of CKD. It is reported up to 60% of cats with CKD have concurrent hyperphosphataemia.

Fats are used frequently in diets for CKD patients to make them more palatable, but also increase calorie content. Foods high in fat should otherwise be avoided due to their relationship with hypertension. Sodium is also used in diets to increase palatability, but studies surrounding the reduction of sodium for CKD patients has produced conflicting results.

Renal oxidative stress (ROS) and oxidative damage is a component of the CKD process. Studies have shown diets supplemented with vitamin C and E, β-carotene and omega 3 fatty acids have shown a reduction in renal injury.

Studies on the supplementation of essential fatty acids have shown promising results for our CKD patients. In studies focusing on dogs with CKD, a diet enriched with omega 3 had much improved survival times. It was also documented that a decrease in intraglomerular hypertension and a maintenance in GFR was seen in the subjects. The use of omega 3 supplementation hasn’t been fully examined in cats yet, but is already showing promise with the reduction of uraemic crisis and increased survival times when commercial diets containing high levels of omega 3 were fed (Plantinga et al, 2005).

Veterinary professionals have access to some of the best prescription diets for renal patients, with the choice of flavours and preparations increasing all the time as the disease becomes more understood.

The veterinary nurse’s role is integral in overseeing the care of CKD patients and spotting the signs of both CKD and AKD in day-to-day practice. Understanding clinical symptoms and predisposing factors of renal disease can allow the nurse to spot early signs quickly.

Veterinary nurses often oversee many aspects of the practice, whether it’s answering the telephone, seeing routine nurse clinics or caring for in-patients; nurses can highlight risk factors or clinical symptoms of renal disease. In the author’s experience, many AKD cases have been triaged by nurses on the telephone or during postoperative checks. Nurses have also picked up minor clinical symptoms of CKD, such as weight loss of PUPD during routine health checks. In all cases, the role of the nurse has led to a much quicker assessment by the veterinary surgeon.

Nurse-led clinics are an excellent way to support clients through the management of CKD. A CKD diagnosis can appear quite final for some owners, or can remain very misunderstood for others. The use of regular nurse clinics can greatly improve owner compliance and understanding for these patients by performing blood pressure measurements, urinalysis, blood samples and weight checks.

The nurse can often spend more quality time with the patient and owner, providing advice and discussing the nutritional management of the disease. Continuity with a veterinary nurse can build trust and familiarity, allowing much improved owner compliance, client service and recognition of developing clinical symptoms.