21 Jan 2019

Leishmaniosis: diagnoses and treatment in travelled or imported dogs

Ian Wright discusses the increasing threat of this vector-borne disease, and how to recognise and manage infection.

Figure 1. Leishmania infantum distribution in Europe, courtesy of the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites. The orange area shows where the disease is endemic. The yellow shows reported cases.

Since the Pet Travel Scheme was relaxed in 2012, pet travel has increased year on year. This, in combination with expanding European parasite and vector distributions, increases the risk of pets and their owners encountering these agents while abroad and bringing them back to the UK. Additionally, importation of pets is increasing the likelihood of novel parasites being introduced.

One of these pathogens is Leishmania infantum, a zoonotic protozoa and cause of lifelong, potentially fatal infection in dogs and cats. Clinical leishmaniosis is being seen with increasing frequency in travelled UK pets, and early recognition, diagnosis and treatment of clinical infection is vital to improve prognosis, prevent spread and allow early long-term management planning for individual patients. Screening of imported pets also forms part of wider pathogen surveillance as this growing trend continues.

Since the Pet Travel Scheme (PETS) was relaxed in 2012, pet travel has increased year on year.

This, in combination with expanding European parasite and vector distributions, increases the risk of pets and their owners encountering these agents while abroad and bringing them back to the UK. Additionally, legal and illegal importation of pets are increasing the likelihood of novel parasites being introduced. Part of this trend has been driven by pets being rescued from abroad and rehomed in the UK. Defra figures report 30,000 dogs were imported into the UK in 2016 and 287,016 UK dogs travelled on the PETS in 2017, up from 164,836 in 2015.

One such exotic pathogen being seen with increased frequency in travelled UK dogs is Leishmania infantum. Leishmania species are vector-borne protozoan parasites capable of infecting a wide range of animals, including dogs, cats and humans. Susceptible cats and dogs, once infected, can remain subclinical for months or years before developing clinical signs. Once they develop, however, they are classically chronically progressive in nature and fatal in severely affected animals. The long incubation periods after infection means travel history in an affected pet may not be recent and infected pets may be imported unwittingly into the country.

Sandflies are the only known vector, but non-vectorial transmission – via venereal and transplacental routes – has been demonstrated and allowed establishment of L infantum in countries where the sandfly vector is not endemic. Transmission has also been suspected between dogs in households without the sandfly vector in Germany and North America. While these non-vectorial routes of transmission are uncommon, they present the potential for limited establishment of L infantum in the UK without the sandfly vector. It is also possible, as the climate becomes warmer, local populations of sandflies – such as those present in France and the islands of Chausey – may spread and establish footholds in the UK.

It is, therefore, vital to recognise the clinical signs of L infantum in travelled pets and confirm an early diagnosis. This allows prognosis to be assessed, clients to be informed of the lifelong treatment risks and for the risk of spread to be minimised.

Distribution in Europe

The prevalence of L infantum in southern Europe (Figure 1), its seasonal expansion into central France and possibly eastern Europe, and the arrival of infected pets in non-endemic countries have increased in recent years. This is due to a combination of factors, including increased movement of infected animals and climate change supporting spread of the sandfly vector. This trend is predicted to continue to grow with the establishment of new endemic foci in central and northern Europe (Pennisi, 2015).

Clinical presentation

The signs associated with Leishmania infection are immune-mediated and in dogs commonly include alopecia, dermatitis, hyperkeratosis, dermal ulcers (Figure 2), polyarthritis, anorexia, weight loss and thrombocytopenia, with associated epistaxis and anaemia. Lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly and granuloma formation may also be present leading to neurological signs if present in the CNS.

Immune complexes may be visible in the eye and lead to associated uveitis. The development of glomerulonephritis with associated proteinuria carries a poor prognosis. Some variation exists in breed susceptibility, with some – such as the Ibizan hound – rarely developing clinical leishmaniosis. Other breeds – such as the boxer, cocker spaniel, German shepherd dog and Rottweiler – are more susceptible to clinical signs developing.

Clinically affected cats commonly develop dermatitis and dermal ulcers, mucocutaneous lesions, gingivostomatitis and lymphadenopathy. More generalised signs are also seen as for dogs, including lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, hepatomegaly, thrombocytopenia and chronic anaemia. Pyrexia may also be seen in cats, and the development of clinical leishmaniosis has been positively correlated with both FIV and FeLV infection.

Diagnosis

Clinical signs are only observed in a proportion of infected animals, and subclinical carriers in endemic countries are common. Diagnostic tests, therefore, need to be interpreted in this light. Leishmaniosis, however, should be considered as a differential in any cats and dogs with relevant clinical signs and travel history. A variety of investigative options are available for suspected cases:

- Fine needle aspirates of lymph nodes or bone marrow: these should be stained with Giemsa or Diff-Quik and examined for amastigotes. These may be extracellular or contained within macrophages. Amastigotes contain two distinct dark areas of pigmentation when stained – the nucleus and the kinetoplast. This is a sensitive method with an experienced examiner, and combined bone marrow and lymph node examination identify about 90% of infected dogs (Roze, 2005).

- Biopsies of skin, lymph nodes or bone marrow: this is a highly sensitive and specific diagnostic method if multiple sites are taken, but also more invasive than other tests. Lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory reaction associated with macrophages infected with Leishmania amastigotes are seen in affected tissues. Histopathological lesions have been found more commonly in organs rich in phagocytic cells, such as spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, liver, gastrointestinal tract and skin.

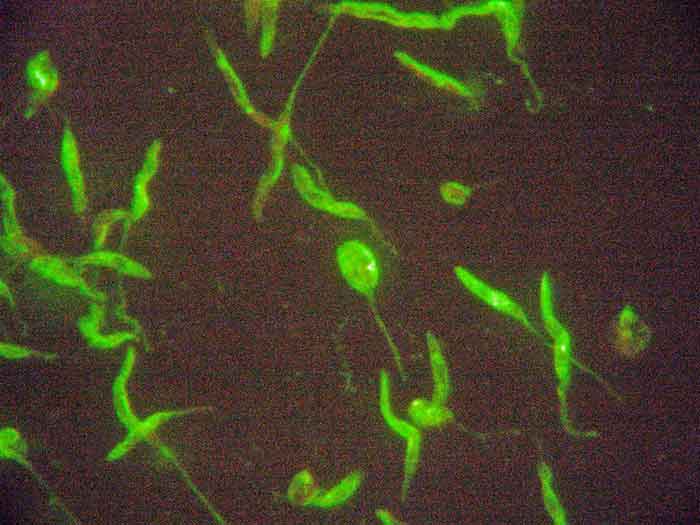

- Serology: sensitivity of serological testing can be low for the first few months following infection, but increases rapidly as infection progresses. Indirect immunofluorescence assay antibody tests (Figure 3) and ELISA tests are commercially available. A positive result does not confirm infection, but quantitative serology allows the size of antibody response to be measured. If this climbs over time, it indicates active infection and is suggestive clinical leishmaniosis is present or about to develop. Quantitative measurement is also useful in monitoring response to therapy or when long-term chemotherapy for leishmaniosis is being withdrawn.

- PCR: PCR carried out on aspirates – or samples of lymph node, bone marrow or spleen – carry a high sensitivity. In comparison, testing blood or urine carries a poor sensitivity (Maia et al, 2009; Solano-Gallego et al, 2011). PCR testing on conjunctival swabs has proved to be an effective non-invasive technique, with sensitivity and specificity of 78.4% and 93.8%, respectively (Geisweid et al, 2013). However, many pets that have spent prolonged periods of time in endemic countries will be positive by PCR as subclinical carriers, and a positive result in these pets does not mean L infantum is necessarily the cause of presenting clinical signs.

Treatment

Before starting treatment, kidney function should be assessed – especially proteinuria. Cases with high proteinuria and/or poor renal function carry a poor prognosis.

Zoonotic risk should also be discussed, but this is very low in the immune-competent owner and a human case of leishmaniosis contracted directly from an infected dog has never been recorded. Owners undertaking treatment for their pets should be aware a lifetime of treatment and monitoring is likely to be required at considerable cost, and repeated clinical episodes are likely to occur throughout the infected patient’s life.

Treatment consists of allopurinol at 10mg/kg twice daily orally in combination with meglumine antimonite (100mg/kg IV or SC every 24 hours for 3 to 6 weeks, or miltefosine 2mg/kg orally every 24 hours for 4 weeks). The latter has the advantage in renal compromised patients of being metabolised solely by the liver. Gastrointestinal side effects from its use are common, however.

Treatment with allopurinol alone may be required for up to six months after resolution of clinical signs to prevent relapse; some patients will need to remain on the drug indefinitely. Quantitative serology every three to six months is useful, as rising titres can act as an early sign clinical leishmaniosis may be imminent. This is particularly important if treatment is being withdrawn in the subclinical patient. Supportive treatment for hepatic and renal function may also be required.

In cats, allopurinol is used alone as other drugs used for treatment in dogs are not well tolerated. The immune-regulating drug domperidone is licensed for treatment of leishmaniosis in continental Europe; therefore, imported dogs already on treatment may be being managed with a regime including this drug. Evidence on the efficacy of domperidone is mixed, but is an alternative to conventional treatment where none of the drugs required are tolerated.

Control and prevention of zoonotic exposure

Disease prevention is essential for dogs travelling to endemic countries. The use of insecticides with “knock-down” capabilities to prevent flies from biting are required. Pyrethroids are the drug class of choice and licensed spot-on preparations are available for dogs. Long-acting collars are also available, but efficacy will be reduced by frequent swimming and/or shampooing of the pet. Seresto collar now has a licence for reduction of transmission of Leishmania (tested in endemic countries), but does not carry a specific fly repellency licence.

Treatment should be applied one week before travel as pyrethroids take time to reach full distribution and activity. No fly repellent is 100% effective, so other preventive measures should also be taken for dogs and cats travelling frequently or for long periods to endemic countries. Commercial vaccines aimed at disease prevention can be used additionally, but not as a substitute for a fly repellent. The latter allows differentiation between vaccinated and infected pets. Avoiding activity outside at dawn and dusk, sleeping upstairs and camping in breezy locations will also reduce sandfly bites as they are poor fliers.

Simple steps to prevent imported pets with Leishmania spreading infection include preventing breeding and, if possible, not rehoming with uninfected pets. Keeping large groups of infected dogs together in “leish clubs” after importation is also not advisable, as this will increase density of infection for sandflies if they establish and increase the risk of adaptation to other vectors. This has already occurred in the closely related parasite, Trypanosoma vivax, in South America that successfully made the transmission from tsetse flies to midges and horseflies via imported cattle.

Zoonotic risk is low in the absence of the sandfly, but has occurred through contaminated needles and blood transfusions. Good hand hygiene should be maintained around infected pets and needles used on patients safely disposed of, and infected pets should not live with severely immune-suppressed people.

Managing the risk of L infantum infection in imported pets is just one aspect of exotic pathogen and disease control in imported dogs. Due to the ongoing risk imported parasites represent to individual pets, owners, the wider public and UK biosecurity, the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites UK and Ireland recommend four key steps (the “four pillars”) when dealing with imported pets on arrival in the UK:

- Check for ticks and identify any found – identification of ticks allows the introduction and distribution of exotic tick species to be monitored in the UK, but also indicates which tick-borne diseases the imported pet may have potentially been exposed to.

- Treat dogs again with praziquantel within 30 days of return to the UK and treat for ticks if treatment is not already in place – this will ensure Echinococcus multilocularis is eliminated from imported pets, whatever the timing of their compulsory treatment, or if doubt exists about it having been administered. Tick treatment will increase the likelihood of attached ticks being killed if they are missed on examination. Ticks are easily missed in large or long-coated breeds, and in cats and dogs reluctant to be examined.

- Recognise clinical signs relevant to diseases in the countries visited or country of origin – a thorough and comprehensive clinical exam of imported pets will identify adverse clinical signs. These can then be compared to common exotic parasitic diseases and those in the countries the pet has visited.

- Screening for Leishmania species and exotic tick-borne diseases in imported dogs – both L infantum and tick-borne diseases can have long incubation periods and carrier states. Infection can also be lifelong and, in some cases, can carry a poor prognosis. Screening for these parasites will lead to early diagnosis, preparing the owner for what could be a lifetime of potential treatment and any associated zoonotic risk. Quantitative serology is a useful screening test for L infantum, as it allows some assessment of titres over time and whether infection is likely to be related to any developing clinical signs. Conjunctival PCR is also useful, but many dogs that have lived in endemic countries will be positive.

Conclusion

L infantum in both cats and dogs represents a lifelong, potentially fatal infection, which is spreading across Europe from its traditional endemic locations in southern Europe. Increased pet travel and importation is increasing the risk of it being seen in first opinion practice and establishing in the UK.

Early detection and diagnosis of leishmaniosis is, therefore, vital to both manage individual patients effectively, but also prepare owners for a lifetime of potential treatment for their pet. Screening and vigilance in imported pets is becoming increasingly important as this trend grows, but so too is raising awareness among owners regarding the risks and possible ramifications of adopting pets from abroad.