8 Jul 2019

Lower urinary tract disease and other urethral disorders in cats

Sarah Caney describes how accurate diagnosis of urinary disorders in patients is often vital to successful management.

Figure 2. Lateral positive contrast urethral radiograph from a cat with a prostatic carcinoma. The cat was presented for haematuria and dysuria, but cystocentesis collected samples were normal. A filling defect can be seen in the prostatic urethra.

Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) is subdivided into obstructive and non-obstructive disease. Cats with obstructive disease are unable to pass urine, often referred to as blocked cats. Urethral obstruction is a veterinary emergency – cats with this condition may die within two to three days if not treated.

Cats with non-obstructive disease are able to pass urine and typically strain to pass small amounts of urine on a very frequent basis. The urine may appear abnormal (for example, bloody), the cat may show signs of pain when straining and periuria may be present due to the cat’s urgency to urinate. Causes are summarised in Table 1.

| Table 1. Major causes of feline lower urinary tract disease | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Approximate frequency in cats younger than 10 years of age | Approximate frequency in cats 10 years of age and older |

| Feline idiopathic cystitis | 55% | 5% |

| Bacterial urinary tract infection | 5% | 50% |

| Urolithiasis | 20% | 10% |

| Urethral plugs | 20% | 10% |

| Bladder neoplasia | Less than 1% | 5% |

| Urolithiasis plus infection | Less than 1% | 15% |

| Incontinence | Less than 1% | 5% |

Urethral disease is less common. Causes include:

- Traumatic damage including rupture, urethritis, stricture formation – for example, following a road traffic accident, urolithiasis, bite wounds, catheterisation of the urethra or surgery.

- Neoplasia. Urethral transitional cell carcinoma and urethral leiomyoma have been reported in the literature. Prostatic neoplasia is rare in cats, but in some reported cases urethral obstruction and/or urethral lesions have been described leading to haematuria and dysuria.

- Anatomical malformation – for example, urethral prolapse and urethral diverticulum (rare).

- Urethral intussusception has been described in association with urethral obstruction.

In cats with urethral disorders, one feature may be abnormal urinalysis on a free catch sample while cystocentesis analysis is normal.

How are FLUTD and urethral disorders diagnosed?

Diagnosing the cause of FLUTD is especially important in cats that show repeated episodes or where the clinical signs are persistent. Diagnosis may require a full behavioural and clinical history, physical examination, blood and urinalysis, imaging (including contrast radiography) and possibly biopsy of the urinary tract.

Clinical history-taking

Typical clinical signs of FLUTD include dysuria, haematuria, pollakiuria and periuria. Acute episodes of FLUTD can be very distressing for cat and carer.

Feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC), the most common cause of FLUTD in cats is considered to be an anxiopathy – a disorder related to chronic activation of the central threat response system (CTRS). It is thought this may develop as a result of genetic, familial and developmental factors. For example, a traumatic experience to the queen when the kitten is in utero may sensitise the CTRS, leaving the newborn kitten susceptible to problems in the future. A susceptible cat is one with a chronic perception of threat impacting on its nervous, endocrine and immune systems with the end result of clinical signs related to a number of organ systems including the bladder and lower urinary tract (Westropp et al, 2019).

The clinical signs of FLUTD are interpreted to be the bladder’s response to stress in these cats. Stress, therefore, plays an important role in triggering and/or exacerbating signs of FIC. Chronic and inescapable stresses are thought to be most important. Characteristics of a cat with FIC often include a cat that is asymptomatic when in a “stress-free” environment, but which suffers from relapses of clinical signs when stressed.

Obese cats, and those with a less active lifestyle, are often over-represented. The history in these cases, therefore, may reveal:

- Evidence of chronicity, waxing and waning of clinical signs in response to stressful events (Table 2).

- That a history of familial involvement may exist, for example litter mates suffering similar problems.

- Involvement of other organ systems resulting in clinical signs, such as vomiting, diarrhoea, poor appetite, altered social interactions, lethargy, altered grooming and enhanced pain-like behaviour at the same time as the urinary signs.

A behavioural history is important to look for evidence of tension with other cats in the household/neighbourhood and other causes of stress in the home (Table 2) that may be exacerbating clinical signs. If identified, these represent a key target for intervention.

| Table 2. Suggested stressors associated with feline idiopathic cystitis | |

|---|---|

| Stressor | Comment |

| Multi-cat household | Especially where conflict or tension exists between cats. |

| Moving house | |

| New additions to the home | For example, new baby, new pet(s). |

| Stress associated with urination | For example: • Competition for using a litter box affecting a cat’s ability to access it. • Using a cat litter the cat doesn’t like. • Placing the litter box in an unsuitable location – for example, a litter box overlooked by cats outside the house or in a very busy part of the home. • Providing a dirty litter box. • Providing a litter box that is difficult for the cat to access – for example, an arthritic cat may have difficulty getting into a high-sided box. |

| Sudden change in the cat’s diet | |

| Bad weather deterring a cat from going outside | |

| Building work in the home or garden | Especially if this affects core areas of the house and/or the previous site of urination. |

| Sudden changes in the owner’s routine | For example, working away from home, shift work. |

Physical examination

Of key importance in the cat with FLUTD is establishing whether the urinary bladder is empty or full. A cat with urethral obstruction and a full bladder needs emergency treatment. Many cats with FLUTD will have an empty, possibly painful, bladder on palpation and the remainder of the clinical examination may be unrewarding.

Laboratory tests

In non-obstructed cats with signs of FLUTD, blood profiles are often unrewarding, but these are important to include in any obstructed cats where dehydration, electrolyte and acid-base disturbances are common. In older cats, signs of FLUTD may be associated with illnesses such as diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperthyroidism and chronic kidney disease, so routine blood profiles are helpful in making an accurate diagnosis.

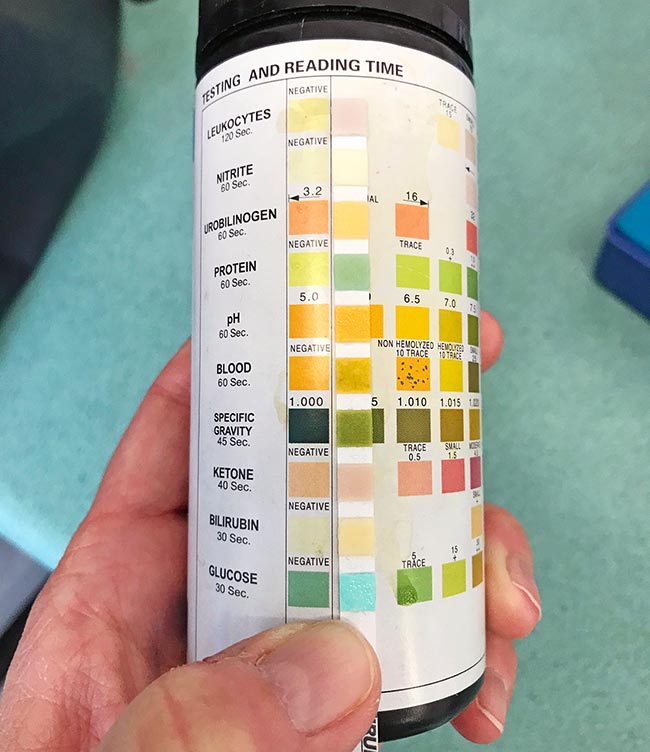

Urinalysis is a key component of investigations in all cats with FLUTD. Urine should be observed and its colour, clarity and presence of gross contamination determined. The urine specific gravity (USG) should be assessed using a refractometer. Urine may be defined as isosthenuric (USG = 1.007 to 1.015, same as glomerular filtrate), hyposthenuric (USG less than 1.007) or hypersthenuric (USG more than 1.015). A 5ml urine sample can be centrifuged and the sediment stained and examined by light microscopy. Normal findings are summarised in Table 3.

| Table 3. In-house urinalysis and interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Normal findings | Comment |

| Urine specific gravity (USG) | Usually 1.040 to 1.060 | Always assess using a refractometer and not a dipstick. USG can be reduced by physiological causes (for example, eating a liquid diet), iatrogenic causes (for example, furosemide treatment) and pathological causes (for example, chronic kidney disease). USG can be increased by heavy glucosuria, heavy proteinuria and presence of radiographic contrast material. |

| Dipstick | Glucose: negative | A positive reading for glucose on a dipstick indicates glucosuria due to either stress, diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperglycaemia due to receiving glucose-containing IV fluids or, rarely, renal tubular disease. |

| Ketones: negative | A positive reading can be found in some cats with DM. Occasionally, ketones will be seen in non-diabetic cats that are in a catabolic state. | |

| Blood: negative | Dipsticks are sensitive in detecting small amounts of red blood cells, haemoglobin and myoglobin – all of which can produce a red discolouration of the urine and positive reaction for blood on a dipstick. | |

| pH: 5.5 to 7.5 | Urine pH may be affected by diet, stress (hyperventilation), acid-base disorders, drugs, renal tubular acidosis and urinary tract infections. | |

| Protein: most cats give a negative/trace/+ reading | Dipsticks are relatively insensitive in documenting proteinuria and do not take into account the concentration of the urine. The urine protein to creatinine ratio (UPC) is recommended in all cats with known renal disease or where protein assessment is required. | |

| Bilirubin: negative | In contrast to dogs, bilirubin should not be present in normal cat urine. | |

| Sediment | Normal feline urine should contain: • Less than 10 red blood cells per high power field (×400) • Less than 5 white blood cells per high power field (×400) • Epithelial cells (numbers greater in free catch versus cysto samples) • +/- struvite crystals (see comment) |

According to the method of urine collection (free catch versus cystocentesis): • Presence, type and quantity of epithelial cells may vary. • Neoplastic cells from the bladder, urethra and prostate may be seen. • Microorganisms should normally not be seen in feline urine, but may be present due to contamination of free catch or mid-stream samples. Casts formed from protein and cells in the distal tubule may be identified. A few hyaline (protein) casts are a normal finding, but excessive casts indicate renal disease, and material trapped in casts may indicate the aetiology (for example, leukocyte casts suggest inflammation/infection – for example, due to pyelonephritis). Struvite crystalluria is common in normal cats. Due mainly to a reduction in temperature (and change in pH), an increase in crystalluria due to additional precipitation will often occur after urine is collected. In assessing the significance of crystalluria, it is important to consider the type of crystal and quantity. Urate crystals can be seen in cats with hepatopathies (for example, portosystemic shunts) and oxalate crystals can be found in hypercalcaemic cats. Heavy crystalluria is a risk factor for urolithiasis and crystal-matrix urethral plug formation. It is important crystalluria is not over-interpreted. In many cases of idiopathic lower urinary tract disease, crystalluria is a normal (incidental) finding. |

| UPC | Less than 0.4 | Guidelines for patients with chronic kidney disease (International Renal Interest Society, www.iris-kidney.com): • Less than 0.2 – not proteinuric • 0.2 to 0.4 – borderline proteinuria • More than 0.4 – proteinuria |

Of prime importance for chronic/repeat cases are:

- Assessment of USG using a refractometer. Most cats with FIC will produce very concentrated urine with a high USG (for example, more than 1.050). Cats with concurrent diseases, such as chronic kidney disease, hyperthyroidism and DM, will typically have a reduced USG (less than 1.035).

- Utility of the dipstick. It is important to remember dipsticks are unreliable for a number of parameters. For example, healthy cat urine commonly produces a reaction on the leukocyte pad so a positive leukocyte reaction should not be taken as diagnostic for a bacterial urinary tract infection (UTI; Figure 1).

Dipsticks are helpful in identifying the presence of glucose and ketones consistent with a diagnosis of DM, bilirubin in jaundiced cats and blood in microscopically haematuric cats.

- Sediment examination. More helpful than a dipstick in identifying signs of a bacterial UTI, sediment examination can also help identify crystals, casts (Table 3).

- Bacterial culture. While bacterial UTIs are not the most common cause of FLUTD, it is important to rule this out as a potential cause.

Imaging

Imaging via radiography and ultrasonography is recommended for cats suffering from repeated/persistent clinical signs. FIC is a diagnosis of elimination. The role of imaging is to rule out other causes of the clinical signs, such as urolithiasis and neoplasia (Table 1).

Positive contrast urethrography can be helpful in identifying urethral disease (Figure 2). Advanced imaging, such as CT is being performed more frequently in cats with FLUTD and excretory urography CT is now a recommended technique for ectopic ureter investigation.

Biopsy

In a small number of cases a biopsy of the bladder or other associated lower urinary tract tissues may be indicated to confirm a diagnosis.

Management of cats with FLUTD

Management of FLUTD depends on the diagnosis made. In all cats with FLUTD there are likely to be benefits from strategies that increase water intake (Table 4) and reduce stress through providing adequate resources for all social groups within the household. Providing an “optimal” toileting facility is also vital.

| Table 4. Strategies to encourage increased water intake in cats. | |

|---|---|

| Factor | Comment |

| Type of water bowl | Most cats prefer glass, ceramic or stainless steel – experiment by offering different shapes and sizes of bowl. Most cats like wide, shallow bowls, but some like drinking out of a tall glass or jug. |

| Fill the bowl to the brim | Most cats do not like to put their head inside the bowl, so fill it to the brim. |

| Number of water bowls | Water bowls should be available in all areas of the home and the cat should be able to access water easily, without competition from other cats. |

| Location of water bowl | The water bowl should not be next to food bowls, litter trays or in busy locations. |

| Consider raising the bowl | Older cats (more than 10 years) often have OA, which can make bending over to eat or drink uncomfortable. Water and food bowls can be placed on an upturned bowl or box to lift them by a few inches. |

| Type of water | Try offering collected rainwater, mineral water and tap water, and see if the cat has a preference. |

| Temperature of water | Offer water at room temperature, chilled water tends to be less appealing to cats. |

| Flavoured waters | Examples include the liquid from a defrosted packet of cooked prawns or a drained tin of tuna in spring water. A flavoured water can be created by, for example, poaching chicken or fish in water. The water left after cooking can be offered as a drink (once cool enough). |

| Offering broths | A broth or soup can be made by liquidising cooked fish or prawns in water. |

| Offer moist rather than dry food | Cats will take in more fluid if eating a moist food compared to what they would voluntarily drink when offered a dry diet. Some “dry food addicts” will eat dry food to which water is added. |

| Moving water sources can be popular | For example, water fountains, a tap left dripping, a ping-pong ball in a wide shallow bowl, so the cat can play with this. |

| Type of diet | Some therapeutic diets encourage increased water intake. |

Cats with FLUTD should have access to a litter box, which should be:

- Generous in size. It should be at least 1.5 times the length of the cat’s body from nose to tail base (Figure 3).

- Easy for the cat to get in and out of. For elderly cats with OA, having a low-sided access point can be an advantage.

- Contain a fine, sandy consistency clumping cat litter: this is most comfortable for the cat to stand on and is most inviting to them as a substrate. Faeces and clumps of urine should be removed at least twice a day and the entire tray emptied, cleaned and refilled at least once a week.

- Perfumed litters, litter tray liners and covered litter trays should be avoided. These are all orientated towards the owner and not the cat.

- Make sure adequate numbers of litter boxes are in the household. As a general rule there should be one for each cat plus one extra and these should be in different locations so there is no opportunity for one cat to prevent access to the litter box by another.

Summary

FLUTD is commonly encountered in clinical practice. A detailed history, including a behavioural history, is often vital to successful diagnosis and management of cats. FIC is a diagnosis of exclusion and other causes of FLUTD need to be considered in cats presenting with lower urinary tract signs. All cats with lower urinary tract signs likely benefit from increased water intake, stress reduction and access to an optimal litter box.

References

- Westropp JL, Delgado M and Buffington CAT (2019). Chronic lower urinary tract signs in cats: current understanding of pathophysiology and management, Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 49(2): 187-209.