4 Jul 2016

Sarah Caney discusses some of the ways in which high blood pressure can be diagnosed in cats, using methods such as ophthalmoscopy, and how this can be managed.

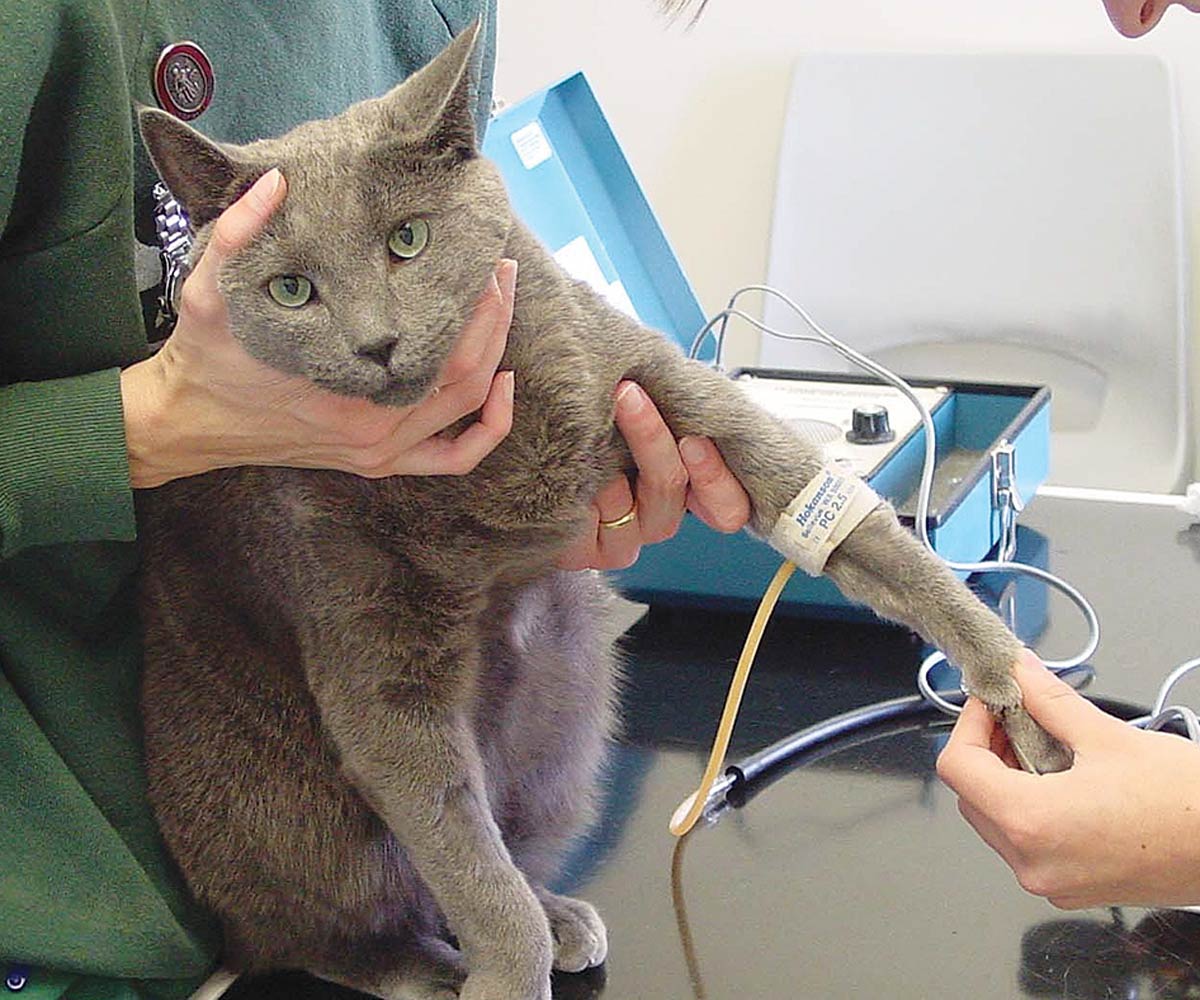

Figure 1. Blood pressure measurement using Doppler methodology.

Systemic hypertension (SH) is a common disorder primarily affecting older cats. SH can be life-threatening, but this condition is often referred to as a “silent killer” as most affected patients have no obvious clinical signs referable to their high blood pressure. If left untreated, affected cats may suffer from visual deficits, neurological signs, cardiac remodelling and renal damage.

Diagnosis depends on measurement of blood pressure that can be challenging in view of the potential for stress-associated increases in readings (often referred to as the “white coat” effect). Examination of the eyes is invaluable in identifying ocular manifestations of SH, such as retinal haemorrhage and detachment.

Amlodipine is an effective treatment for SH and many patients can be successfully stabilised with this. In some patients, additional treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (such as benazepril) or angiotensin receptor blocker (such as telmisartan) can be necessary to stabilise hypertension.

Systemic hypertension (SH) – a persistent increase in the systemic blood pressure (BP) – is commonly recognised in feline practice.

It is especially a common diagnosis in elderly cats (11 years and older) and this condition appears to be on the increase. Several possible reasons for this include an increased awareness of hypertension as a feline problem, access to diagnostic facilities and, possibly, an increased prevalence of this condition related to the advancing age of the cat population.

Idiopathic hypertension (also referred to as primary or essential hypertension) accounts for fewer than 20% of cases and most reported cases occur secondary to other medical problems. The most commonly cited diseases associated with hypertension are chronic kidney disease (CKD) and hyperthyroidism.

Prevalence rates quoted have been highly variable – for example, SH has been reported in 20% to 65% of cats with CKD (Stiles et al, 1994; Syme et al, 2002), and 9% to 23% of cats with newly diagnosed hyperthyroidism (Stiles et al, 1994; Syme and Elliott, 2003).

Other diseases where an association with SH has been reported include primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn’s syndrome), chronic anaemia and in cats receiving treatment with erythrocyte stimulating agents, such as erythropoietin and darbepoetin.

BP measurement and eye examinations are important when evaluating a patient for possible SH. Many patients with SH will not have any clinical signs associated with high BP. Typically, clinical signs referable to SH – called target organ damage (TOD or end-organ damage) – only occur relatively late in the course of disease. Target organs most vulnerable to hypertensive damage are the brain, heart, kidneys and eyes (Table 1).

| Table 1. Target organ damage seen with systemic hypertension | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organ affected | Pathology | Clinical findings | Reported approximate prevalence |

| Brain | Hyperplastic arteriosclerosis of cerebral vessels, oedema of the white matter and microhaemorrhage development resulting in hypertensive encephalopathy, with or without stroke. | Behavioural and/or neurological signs, including night-time vocalisation, signs of confusion/dementia, ataxia, seizures and coma. | 15% |

| Heart | Left ventricular hypertrophy. | New murmur and/or gallop rhythm. | 50% to 80% |

| Kidneys | Glomerular hypertrophy and sclerosis, nephrosclerosis, tubular atrophy and interstitial nephritis resulting in progression of chronic kidney disease. | Reduced urine specific gravity, proteinuria, increasing creatinine levels, increasing symmetric dimethylarginine levels and decreasing glomerular filtration rate. | |

| Eyes | Hypertensive retinopathy/choroidopathy resulting in many changes, including intraocular haemorrhage, retinal oedema, retinal detachment, arterial tortuosity, variable diameter of retinal arterioles, papilloedema and glaucoma. Foci of retinal degeneration (hyper-reflectivity) may develop where damage has previously occurred. | Visual deficits, blindness, mydriasis and hyphaema. | 60% to 80% |

Cats with SH may be presented with signs referable to their underlying systemic disease, such as inappetence and weight loss in a patient with CKD.

BP should be evaluated as a routine part of preventive health care checks in all cats of seven years of age or older, and in younger cats if there is any reason to suspect they may be at risk of hypertension. A reminder of clinical situations where BP assessment should be considered are included in Table 2.

| Table 2. Candidates for blood pressure assessment | |

|---|---|

| Clinical situation | Comment |

| Patients with visual deficits and/or blindness | Unfortunately, this is still a common presentation for patients with SH. Blindness is typically permanent. |

| Patients with ocular conditions where SH is a differential diagnosis | SH may result in a number of ocular changes (Table 1). |

| Patients with chronic kidney disease | About 20% to 65% of these patients are thought to suffer from SH. |

| Patients with hyperthyroidism | About 10% to 20% of these patients are thought to suffer from SH. |

| Patients with primary hyperaldosteronism | Affected patients may have hypokalaemia and SH. |

| Patients with unexplained proteinuria | Consider SH as a cause of this. |

| Patients with cardiac abnormality/abnormalities detected on clinical examination, such as murmur and gallop | Persistent SH results in cardiac remodelling – left ventricular hypertrophy – which can result in a new murmur or gallop in up to half of patients. |

| Patients with left ventricular hypertrophy identified on echocardiography | Rule out SH before diagnosing primary HCM. |

| Patients with behavioural or neurological signs (especially older cats) | Hypertensive encephalopathy may result in signs of dementia and other behavioural/neurological signs (Table 1). |

| Older cats | Ideally assess blood pressure in all cats aged seven years and older, at least once a year. |

| Other | Illnesses where a link with SH has been documented include chronic anaemia and erythropoietin/darbepoetin therapy. |

| HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, SH = systemic hypertension | |

Ideally, diagnostic evaluation should include systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) measurement (Table 3). Little information on diastolic hypertension exists. However, in other species it is known to be an important cause of vascular damage.

| Table 3. Classification of blood pressure in cats (in mmHg) based on the risk of future target organ damage (TOD; Brown et al, 2007) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk category | Systolic blood pressure | Diastolic blood pressure | Risk of future TOD |

| I | <150 | <95 | Minimal |

| II | 150 to 159 | 59 to 99 | Mild |

| III | 160 to 179 | 100 to 119 | Moderate |

| IV | ≥180 | ≥120 | Severe |

The author favours the Doppler technique for measurement of BP in conscious cats (Figure 1). This technique reliably gives SBP readings in all cats with DBP readings possible, with practice, in more than half of patients (Jepson et al, 2005). Techniques for BP measurement are reviewed elsewhere, including on the author’s website (Caney, 2015).

Regardless of methodology, the most reliable BP readings are obtained by allowing the cat to acclimatise to the surroundings prior to measurements being taken and the procedure being performed in a calm and quiet location.

The author generally favours measuring BP as an “outpatient” procedure with the owner present to reassure the cat. On average, the “white coat” effect increases SBP by 15mmHg to 20mmHg. However, the effect is highly variable between cats and can be as much as 75mmHg (Belew et al, 1999). Tips for reducing the white coat effect are in Panel 1.

The author’s tips for reducing “white coat” hypertension and obtaining reliable blood pressure (BP) readings in your patients

The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) and the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) recommend a reference range of 120mmHg to 149mmHg for SBP readings in cats (Table 3).

Treatment for systemic hypertension is recommended if SBP readings are above 160mmHg, with the following guidance:

A detailed ophthalmic examination is essential both in the diagnosis and assessment of the patient. A thorough ocular examination is easily done using distant indirect ophthalmoscopy in a dark room (Figure 2). This is an ideal way to visualise large portions of the retina very quickly.

Gross abnormalities, including retinal oedema and detachment, intraocular haemorrhage and vessel changes, can be seen (Figure 3; Caney, 2009). Direct ophthalmoscopy can be used to gain a closer look at any lesions identified.

The main goals of management are to:

Irrespective of the nature of the underlying or associated disease, specific management with antihypertensive agents is required in cats diagnosed with SH. For example, in spite of the association between hyperthyroidism and SH, most clinicians find curative treatment of hyperthyroidism is not associated with resolution of SH – in other words, these patients tend to need antihypertensive management for the rest of their lives.

Amlodipine is a veterinary licensed treatment for feline hypertension and generally extremely effective as a sole treatment for SH (Huhtinen et al, 2015). Typical doses of 0.625mg or 1.25mg per cat per day can be increased to 0.5mg/kg per day, if needed (Table 4).

| Table 4. Antihypertensive agents commonly used in cats | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Class of agent | Agent/s and oral dosage regime | Effective? | Comments |

| Calcium channel blocker | Amlodipine: 0.625mg to 1.25mg per cat q12h to q24h (maximum suggested dose 0.5mg/kg/day). | Very: typically reduces SBP by 30mmHg to 50mmHg. | Often effective as sole therapy. Benazepril or telmisartan can be added if ineffective at the stated doses. |

| ACEI | Benazepril: 0.25mg/kg to 0.5mg/kg q12h to q24h. | Mild to moderate: typically reduces SBP by 10mmHg to 20mmHg. | Benazepril is often ineffective as a sole therapy, especially in cases of marked hypertension (SBP above 180mmHg). In these cases, a combination of benazepril and amlodipine is usually very successful. |

| ARB | Telmisartan: 1mg/kg q24h | Mild to moderate: typically reduces SBP by 10mmHg to 20mmHg; possibly greater efficacy at higher doses. | Less data available for telmisartan – the author understands studies are underway to assess the efficacy of telmisartan for management of SH in cats. Telmisartan can be used in combination with amlodipine, at the doses stated, where needed. |

| ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker, SBP = systolic blood pressure, SH = systemic hypertension | |||

Response to therapy should, ideally, be monitored after seven days of treatment by measuring SBP and monitoring TOD. In successfully treated cases, BP should drop to levels between 120mmHg and 149mmHg within 7 days of initiating therapy.

Post-treatment BP readings between 150mmHg and 160mmHg are acceptable as long as no evidence of continued TOD exists. In some cases, it may be necessary to use a combination of amlodipine and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI; such as benazepril) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB; such as telmisartan) to achieve an adequate response (Table 4).

Although not licensed for treatment of SH, ACEI and ARB do have mild potency in reducing BP when used at their standard doses, and may be sufficient as a sole therapy in mildly affected cats (SBP below 180mmHg). An ACEI or ARB, or in combination with amlodipine, may be preferred in cats with concurrent CKD where both ACEI and ARB are licensed medications for the management of proteinuria associated with CKD.

Where possible, following diagnosis of SH, investigations for underlying diseases and those known to have an association with SH are indicated. Ruling out CKD and hyperthyroidism is the initial priority, so laboratory investigations should include serum thyroxine (T4), blood urea and creatinine and urinalysis. SH may result in mild proteinuria, so the SH should be treated and the patient re-evaluated to determine whether proteinuria is a persistent abnormality.

If initial laboratory work does not reveal an obvious cause of the SH, additional diagnostic tests that may be considered include:

Once BP is within the reference range, patients should be assessed every one month to two months, reducing the frequency to a minimum of once every three months to four months in very stable patients. Follow-up assessments should include:

The long-term prognosis is dependent on the presence, nature and extent of any underlying disease.

In primary hypertensive cases, it is usually possible to manage the hypertension and prevent future complications, such as ocular haemorrhage. Management of SH improves clinical status, even in cats suffering from blindness.