15 Jul 2025

Emma Brown BVSc, PGDip, CCAB, MRCVS discusses this common problem for dogs and owners, the impact of which is not just present in autumn.

Image: dambuster / Adobe Stock

Fears and anxieties related to noises are very common in dogs. A 2020 study by Salonen et al found a prevalence of 32% in Finnish dogs, and in a 2013 study by Blackwell et al, almost half of UK dog owners reported their dog showed at least one behavioural sign associated with fear when exposed to loud noises.

Traditionally, noise sensitivity has often been viewed as a seasonal problem in veterinary practice, with cases presenting around the fireworks season. The aim of this article is to look beyond this traditional view and consider the dogs impacted by anxiety related to noise throughout the year.

PDSA’s annual welfare report from 2018 stated that 40% of pet owners who completed its survey felt their dog was afraid of fireworks; 24% felt they were afraid of thunder and lightning; and 24% felt they were afraid of loud noises in general.

Although often considered together, anxiety and fear are distinct. Fear is an acute adaptive response to an actual or perceived threat. Anxiety is a more chronic state characterised by the anticipation of potential future dangers or negative outcomes.

When considering the year-round impact of noises on dogs, we must consider both dogs showing repeated fear responses to noises through the year, but also that anxiety relating to noises can persist well beyond the initiating event.

This anxiety related to noises can present in a range of ways that the clinician might not immediately associate with noises; for example, owners might notice a reluctance to walk in areas where noises have been heard or even to leave the house in extreme cases; separation-related behaviours if the noises have occurred when the dog was alone, or the owner is an important part of the dog’s coping system when exposed to noise; or reluctance to go out to toilet after dark if this was when the noises occurred.

Dogs have very sensitive hearing, and it is likely that in the environments in which their wild ancestors lived loud noises may have predicted a threat. It is, therefore, perhaps not that surprising that a large number of dogs show fear in response to loud noises.

Storengen and Lingaas (2105) identified some risk factors for the development of noise fear, which were genetics, breed and gender, with female dogs more likely to present with noise sensitivity.

Development of fear in an individual can relate to lack of exposure or negative experience during the critical periods of development or traumatic events related to loud noises. These can result in enduring fear response to loud noises.

It is common for the fear shown in response to noises to increase over time (Dale et al, 2010) and for owners to see the dog respond negatively to an increasing number of noises. This is known as generalisation, and it has been suggested that generalisation may be particularly common with noise fears, and the types of noise that dogs respond negatively to are often similar: high decibel, lacking patterns and may be hard for the dog to localise (Levine, 2009).

Dogs are good at identifying contextual cues associated with salient triggers, and when dogs present with significant aversion to noises, we often see signs of fear or anxiety in situations that the dog associates with the noise.

If this dog happens to live in an environment in which noises are common or if the dog’s fear has generalised to include a wide range of normal domestic noises, we can see a state of chronic anxiety, with the dog almost constantly anticipating a noise event.

In addition to a full medical exam and thorough behavioural history, some useful tools can be used in the assessment of these cases, which can help the clinician understand the impact the fear and anxiety are having on the dog.

To assess the impact of an acute noise event, we can use the Lincoln Sound Sensitivity Scale for Dogs. This can be combined with the Positive and Negative Activation Scale for dogs to give a better understanding of the dog’s temperament and how this might influence treatment outcomes.

Full assessment of any dog showing anxiety should include evaluation of any medical or behavioural comorbidities. Some medical conditions can predispose to development of noise sensitivities, and it should also be considered that chronic anxiety can impact physical health.

Repeated exposure to triggers or sensitisation and generalisation with ongoing anxiety can result in chronic stress, which can lead to dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, with effects across different brain areas as a result of excess corticosteroid exposure, leading to impaired learning and memory, as well as effects on the general health status of the animal (Notari, 2009).

Behavioural comorbidities are common in dogs showing fear/anxiety related to noise. Storengen and Lingaas (2015) found that the dogs most fearful of noises also had higher odds of showing separation-related behaviour, being fearful in novel situations and required longer time to calm down after a stressful event compared to dogs less fearful of noises.

Clinicians should also consider the possibility of a medical factor in noise anxiety.

Mills et al (2020) reported that pain may be a contributory factor to behavioural problems in 28% to 82% of cases.

In addition to pain, other medical conditions can be associated with the development of noise-related fears such as cognitive dysfunction (Landsberg et al, 2011) and hypothyroidism (Aronson and Dodds, 2005).

Administration of corticosteroids may also impact on development of noise sensitivities.

Successful management of noise anxiety requires a comprehensive assessment and tailored plan. The following should be considered.

Preparation for noise events. Ongoing exposure to triggers causes distress and can result in further sensitisation. Whenever possible, triggers should be avoided or minimised. Clients should be given detailed instructions on how to manage a noise event – this might include walking before the noise starts; feeding a light meal prior to the noise; ensuring access to the dog’s safe area; closing curtains and playing music or white noise; provision of high-value chews, lick mats or stuffed food toys; ear defenders (with appropriate prior habituation and reinforcement of wear); and advice on use of situational medication.

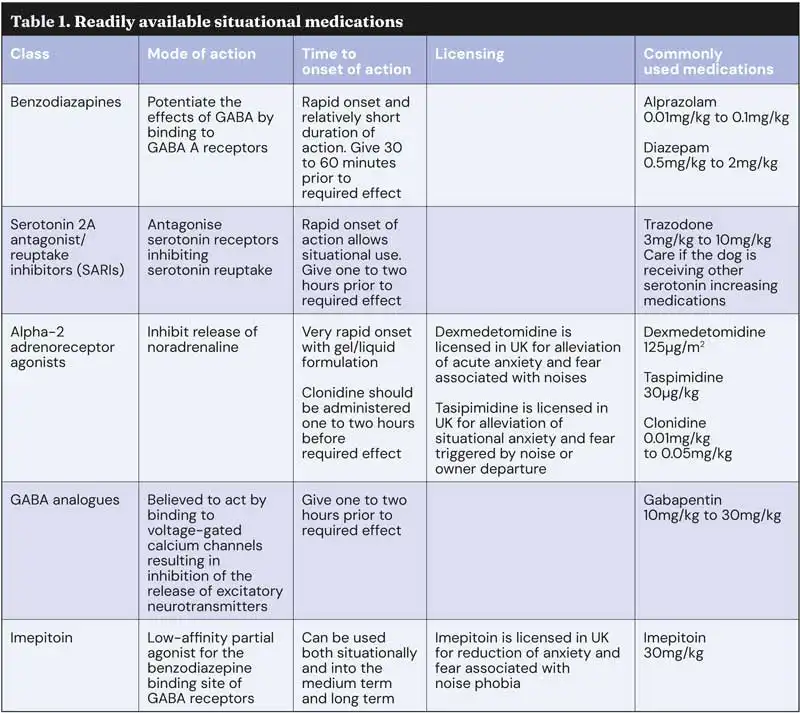

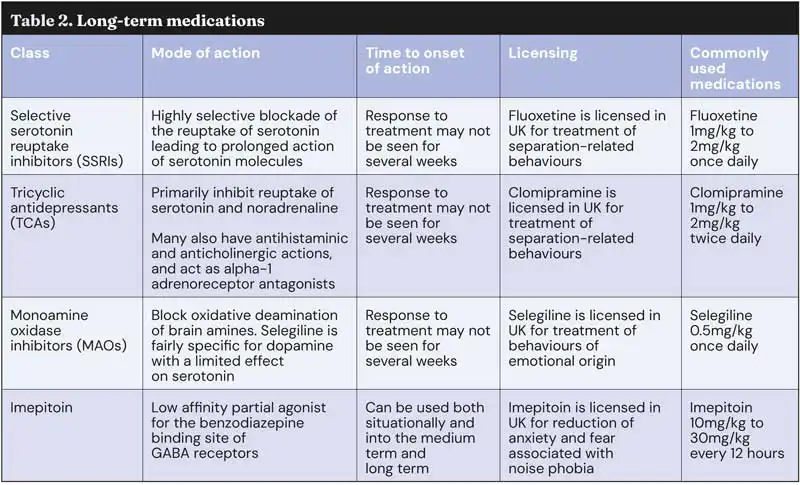

Psychopharmacology. The use of appropriate medication will be integral to management in most cases. Situational medication should be considered for any dog that has shown signs of stress relating to sound if the trigger cannot be avoided to prevent further sensitisation. Table 1 gives information on the readily available situational medications. In some cases – especially those with significant generalisation or anxiety in response to contextual cues – long-term medications will also be indicated. Table 2 gives information of long-term medications appropriate for use in sound sensitivity cases.

Provision of a safe den area. Providing an appropriate den area (in the most sound-insulated area of the home or the location the dog has chosen, if appropriate) and reinforcing choice to use this area gives dogs the opportunity to choose a strategy which helps them cope.

Desensitisation and counter-conditioning. Desensitisation involves gradually exposing the dog to incrementally increasing levels of the trigger always remaining below the threshold that triggers fear. In counter-conditioning, the stimulus is paired with a positive outcome. This is generally carried out using high-quality sound recordings, so that the volume and timing can be closely managed, and the aim is for the dogs to always remain relaxed during desensitisation and show a positive emotional response to counter-conditioning. Counter-conditioning can also be used in real-world scenarios, offering high-value food or play as soon as the noise is heard. Although care must be taken not to cause further sensitisation, this real-world learning can be very powerful. In a review of treatment techniques, more than 70% of dogs managed using this sort of ad hoc counter-conditioning showed improvement (Riemer, 2020).

Relaxation training. A variety of techniques have been used to condition relaxation behaviour in dogs and this has been found to be effective in some cases (Reimer, 2020).

Pheromones. Levine and Mills (2008) found that adding dog appeasing pheromone to the treatment protocol resulted in improvements in response to desensitisation and counter-conditioning being maintained for longer.

Others. A wide range of nutraceuticals and adjunctive treatments have been suggested. So far, high-quality research into the efficacy of these for noise fear/anxiety is limited.

For many dogs, noises are not just a seasonal concern. The environment in which most domestic dogs live is filled with potential noise triggers (household appliances, smoke alarms, power tools, aircraft, bird scarers and many others).

Anxiety relating to noise events can have a huge impact on the welfare of affected dogs, with the worst-affected individuals unable to leave their “safe area” and struggling to engage in any positive activity.

These cases are hugely satisfying to work with, but severe cases are probably best referred to an appropriately qualified clinical animal behaviourist or veterinary behaviourist.

Use of some drugs in this article is under the vet medicine cascade.

EMMA BROWN qualified as a veterinary surgeon in 2001. She spent 15 years in mixed practice, completing a postgraduate diploma in animal behaviour and welfare in 2014 before moving to small animal practice in 2016. Emma is an RCVS Advanced Practitioner in Companion Animal Behaviour and a Certificated Clinical Animal Behaviourist (CCAB), listed by CCAB Certification. Emma runs a behaviour referral service for Kernow Vets in Cornwall, taking canine and behaviour cases from across the south-west.