2 Sept 2020

Management of multiple trauma injuries in a male cocker spaniel

Tom Hinchliffe describes the case of four-year-old male neutered cocker spaniel Harley.

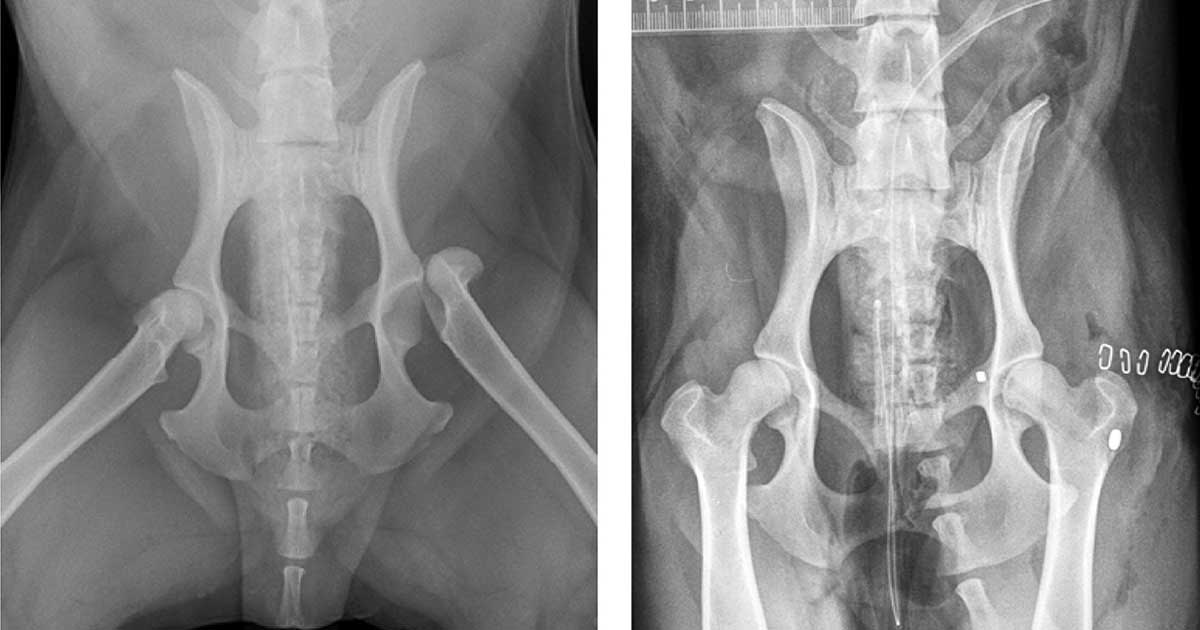

Figure 1. Preoperative and postoperative radiographs of the ventrodorsal hips showing fixation of a left coxofemoral luxation using a “toggle” procedure.

You are presented with Harley, a four‑year‑old male neutered cocker spaniel that had been hit by a car one hour earlier.

On physical examination, he is conscious with normal mentation, but is tachypnoeic, tachycardic, with pale mucous membranes and cold extremities, and recumbent. Thoracic auscultation is normal, but he has extensive bruising across his abdomen.

Harley responds very well to stabilisation with analgesia and IV fluid therapy. He is given IV antibiotics and radiographs are taken under general anaesthesia, revealing a complete transverse fracture of the right tibia and fibula, as well as a luxation of the left coxofemoral joint. You reduce the left hip joint in a closed fashion, and place a modified Robert Jones bandage to support the fractured tibia.

Harley takes a long time to recover despite continued supportive therapy. Blood starts to come out of his rectum profusely, and his abdominal circumference seems to increase.

Question

What is your interpretation of the clinical findings and how would you manage this case?

Answer

Harley’s slow recovery may either be due to hypovolaemic shock not being addressed long enough prior to general anaesthesia, or the ongoing consequences of shock not being counteracted by the resuscitation. General anaesthesia may be a “second hit” to Harley’s hypovolaemic state.

Cardiovascular parameters must be monitored closely in these cases. Ventricular premature complexes were noted on ECG, suggesting a traumatic pericarditis. As no further haemodynamic consequences occurred (as determined by heart rate, oxygenation and blood pressure), this did not warrant treatment, but was monitored closely.

The rectal bleeding may be colitis in response to shock, or due to blunt trauma rupturing intestinal vessels or perforating the intestinal wall. Rectal examination would help assess the pelvic canal, as well as the integrity of the colon and urethra, while checking for presence of further bleeding.

An increasing abdominal circumference suggests either gas or fluid buildup within the abdomen. Ultrasonography can help determine intestinal integrity, as well as the presence and source of free fluid.

Cytological examination of abdominocentesis can also help confirm the nature of the fluid, as well as the presence of any faecal material that may indicate intestinal rupture. In this case, a haemoabdomen was confirmed.

Sequential monitoring of the haematocrit, and biochemistry of peripheral blood and abdominal fluid can give an indication of how stable the haemoabdomen is. This helps the decision on whether an exploratory laparotomy is required.

If bleeding is stable, the haematocrit of the haemoabdomen will increase in relation to the peripheral blood, as abdominal fluid is absorbed and the peripheral blood is diluted with continued IV fluid therapy. A compressive belly bandage is sometimes warranted to aid haemostasis, but must be monitored closely not to cause ischaemia.

In this case, the haemoabdomen was stable and the rectal bleeding was confirmed as colitis, resolving over 24 hours, along with the ventricular premature complexes. Further stabilisation and intensive monitoring was continued for five days until it was safe enough for surgical fixation of the orthopaedic injuries (Figures 1 and 2).

Harley had a good recovery (Figure 3) and returned home another five days post-surgery.

Summary

It is important to resist the temptation to investigate and manage orthopaedic injuries early in the treatment process, as these do not require emergency management.

As evident by this case, general anaesthesia lowers blood pressure and worsens haemodynamic parameters. This may cause tissue hypoxia, make resuscitation more difficult and trigger further complications.

Additionally, the neurological status of the limbs is particularly important for a favourable prognosis of fracture stabilisation and requires repeated assessment over time.