14 Apr 2020

Management of OA part 1 – time for a change in direction?

Ross Allan and Stuart Carmichael discuss the potential for practices to set up dedicated clinics for this issue – making use of the whole clinical team, as well as assessment tools and online support.

We encounter patients with OA almost every day in practice – yet despite the range of pharmaceutical, nutritional, biological and physical options now available, the management strategies generally used in practice for the management of OA patients have been slow to develop.

This article sets out factors to consider when managing OA patients and steps the authors believe can be taken by many practices to significantly improve OA patient care. These steps include setting up and running an OA clinic, the importance of having a structured, repeatable means of measuring patient progress, and the importance of using the skills of the whole veterinary team.

Many recent and excellent articles have detailed the increasing number of options available for managing OA in dogs.

In fact, never has a time probably existed when a larger choice of pharmaceutical, nutritional, biological and physical options have been available.

The question, however, remains – are we improving our management of the disease with this wide array of options? If the answer is no, is the problem with our delivery of management, rather than lack of choice?

In a recent article (Veterinary Record, 2018), an owner’s views of their experiences of managing OA in their own dog were captured. They clearly identified the gulf between what we offer as good management, and what an owner’s expectation and needs really are.

It made difficult reading to understand that although the owner said their veterinary practice was supportive, they felt it was not providing the proper time to fully understand both their needs or their pet’s.

As a result, the owner clearly felt they had limited control over what was unfolding and limited ability to reassure themselves that they were doing the right thing for their pet.

In this, the authors feel the real problem lies with the present management of OA in dogs (Figure 1). As a group of professionals, we have greater understanding about the disease and more numerous ways of modifying it, yet have not really changed our basic management approach to dealing with it. We still try to cope with the OA case as part of our normal practice schedules.

In particular, we struggle to create the additional time we know good management requires – the owner in the article highlighted the lack of critical clinical reviews during the course of the disease. This is an essential component of managing a chronic disease such as OA.

However, once a diagnosis has been made, our approach to the disease seldom changes, and is often not really subject to regular assessment and modification.

So, how can we change this?

Managing OA as a lifelong problem

An approach more sympathetic to the real needs of the patient and owner, understands these, and focuses on effective long‑term disease management is essential – and will yield better results.

A change in the way we manage OA cases, to create the time required to achieve this, is clearly required – and while a challenge, continuing to ignore the need to change our present treatment strategies is not wise. It will lead to the same outcomes, and we will lose the confidence and trust of our pet owners.

Establish a dedicated ‘clinic’ for OA cases within the practice

This change has to work for the veterinary practice as well as the owner – so it must be efficient and practical; organised so it augments practice work, rather than disrupts it.

The authors would suggest that in almost all veterinary practices, sufficient cases will have already been diagnosed with OA that could benefit from a dedicated clinic being offered – and once established, new cases can be directed into the clinic.

An OA clinic only needs to be operational one or two days per month initially, to assess and review cases, and diagnostics and treatments can be incorporated into these appointments, or else scheduled separately.

The value of tight scheduling to run an OA clinic means dedicated staff resource can be made available to make the clinic work effectively, without being diverted elsewhere.

Use whole clinical team

Successfully treating and managing OA patients is something the veterinary profession has made valiant steps towards improving over the past 20 years, yet we still fall short of treating this dynamic disease to our full potential.

A number of reasons for this exist, but the authors would suggest many of the present clinical and practice structures that influence the care we provide are inherited, and ill‑suited to managing chronic disease such as OA. Perhaps largely due to them being designed for disease, where the focus is on investigation; diagnosis and treatment, rather than management and maintenance.

An important element of this consideration is time. In small animal practice, with an average preventive health consultation length of less than 10 minutes, it is hardly surprising that many vets and owners describe rushing and minimising discussions to help keep consultations within their allocated time and view (Belshaw et al, 2018).

Likewise, it is inevitable the pace, content and duration of a preventive health care consultation are influential factors in consultation satisfaction (Belshaw et al, 2018).

“A short appointment in a cramped surgery doesn’t give a vet the opportunity to study physical ability, or to discuss in detail the daily problems, possible methods of alleviation, and the owner’s domestic and financial circumstances, or support networks and views on euthanasia.”

(Veterinary Record, 2018)

Despite these time pressures, in most practices, OA care remains vet-centred – not vet-led. In this scenario, vets recheck the patients, review their progress, and amend and update the treatment plan.

This is not wrong, yet given the time pressures that exist, a multidisciplinary approach – led by vets, but involving the wider clinical team who share a common objective of optimising patients’ progress – would be better suited to managing OA patients.

Previous studies into preventive health consultations have described the willingness of some clients to have their care led by nurses, and to use “tick box” or other similar instruments to focus discussions (Belshaw et al, 2018).

Dedicated OA clinics lend themselves to the team approach – enabling each member of the team to have a defined role, opening up more time to enable efficient and effective client and patient management; explaining and updating patient and disease management plans.

It also should help improve the ability to plan for using the clinical space, assessment tools and treatment instrumentation required to make the clinic work.

In the authors’ experiences, clinics that involve more of the clinical team – while requiring effort and structure to set up and maintain – are more likely to be rewarding for the clinical team, as well as being viewed as being successful by owners and beneficial for patients.

Similar clinic models in human rheumatology have also been shown to help improve the service, avoid unnecessary visits, improve collecting patient data, and enhancing the patient experience and journey through the system (Väre et al, 2016).

It is time to change our outlook and move on from “treatment-based” strategies, towards maintenance and management, and get joy – as a clinical team – from managing chronic disease patients.

Use a system

The key thing to achievement is the rigour of constant review, recording the results and responding appropriately.

A systematic approach is needed, using our newly gained knowledge and available technology based on the three principles of assess, implement and monitor (AIM).

The creation of dedicated OA clinics to deliver this approach seems an obvious step.

Stage one: assess

A checklist approach is very helpful in a problem that is re-evaluated repeatedly.

It ensures the same key points are reviewed at each visit. It also means the details recorded are consistent and prevents the reviewer or owner becoming distracted by events that may not be relevant to the ongoing review.

The checklist should prompt a pattern of examination:

- obtain a detailed history

- clinical examination (focused on OA)

- health assessment and check for other disease problems

- record all details for future review

It is impossible to properly reassess a case if the details of the previous examinations or assessments have not been systematically recorded – and this is a discipline that has to be acquired. The importance of recording these details differs from when a case is being treated in the “now”. In this situation, while clinical details are still used to make decisions, recording each specific detail – even if not abnormal or changed – could seem non-essential.

When managing chronic disease such as OA, however, the systematic capture of clinical and functional detail ensures important details are always recorded, and is an efficient use of time and effort.

Stage two: implement

For this stage:

- create a plan to meet objectives using a multimodal system

- on-board owner

- agree a long-term strategy and way it will be delivered

This stage will be explored in more detail in part two.

Stage three: monitor

For the final stage:

- establish regular review dates as part of an ongoing management strategy

- use clinical team to carry out these reviews and deliver specific management interventions

- repeat AIM process

- use measurement tools and record results; compare to previous visit

- share results with pet owner

- revise objectives and management plan depending on assessment

A lifetime disease such as OA needs constant re-evaluation and review. A system of proactive and planned review of an individual patient at set intervals may be the best way to understand the clinical pattern, and best inform management.

This is very different from waiting for the owner to return an affected dog because signs are getting worse or more obvious. Similarly, a review appointment is essentially different from a treatment appointment for physiotherapy, hydrotherapy or similar, although treatment can be delivered after review.

The opportunity to monitor and manage other comorbidities that will respond to this approach will likely be developed – especially in older or geriatric pets.

Use OA assessment tools

Our fallibility in subjectively assessing patients is exposed by the caregiver placebo effect revealing an error of between 40% and 50% in estimating improvement (Conzemius and Evans, 2012).

So, how can we become better at measuring the results of our management attempts?

We are now able to evaluate progress in OA cases by using various measurement tools. These vary from clinical metrology instruments such as Liverpool OA in Dogs (Walton et al, 2013), the canine brief pain inventory (Brown et al, 2008), the Helsinki chronic pain index (Hielm-Björkman et al, 2003) or health-related quality of life (Reid et al, 2018), which can act like a structured checklist to help score the impact OA is having on the patient. They yield a “score” that can be used to view progress at each visit.

Even simple filming of gait on a smartphone and attaching to the patient’s record can help to understand the animal’s status and add changes that have occurred since previous visits.

More physical features, such as joint movement, can be assessed by repetitive goniometry using simple angle-measuring equipment. More sophisticated measurement systems, such as stance analysers or pressure mats, are becoming more available and practical to use for practices; this is likely an area that will gain more interest.

With correct organisation, teams can plan to use these tools as aids in the OA clinic assessment. This will be vitally important when reviewing cases as they are monitored.

Again, dedicated clinics will allow these resources to be ready and available for cases attending for management. Regular use will create a more streamlined and time-efficient experience for the clinical team and pet owner.

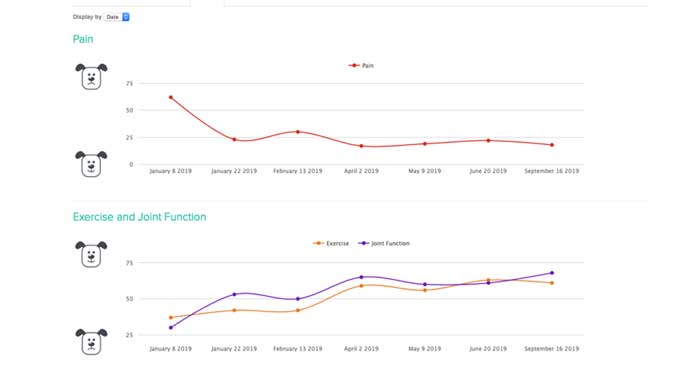

Digital systems, such as Aim.OA, have inbuilt disease tracking systems that can give a good visual representation of the real-time progress, and are invaluable in understanding the impact of management (Figure 2).

The importance of these measuring tools should not be underestimated. They help both the clinical team and owner to see – indeed, visualise and understand – whether progress is being made. Often, progress against key objectives – such as reduction of chronic pain or restoration of muscle mass (Figure 3) – can take time and patience is needed. Measurement can help reassure everyone involved that things are progressing to plan, or propagate discussion of other potential patient management strategies.

Take steps to set up a dedicated OA clinic

To set up a detailed OA clinic:

- Identify the staff who will be responsible for the clinic.

- Establish an arthritis training programme for this group.

- Determine exactly when the clinic will operate; create space (consulting room) and place in calendar.

- Create longer appointments using team to service these.

- Recruit initial cases from existing database. Schedule between 10 and 12 cases per clinic initially (single day):

- advertise in waiting room

- direct approach

- hold owner group meeting to discuss OA and what the clinic will offer

- Decide what assessment and management tools and skills the team will develop, and make these available on clinic days.

Use online and digital support

Resources are now available that can be used as a source of current knowledge and guidance for practices and owners alike. The Veterinary OA Alliance is a new group aimed at bringing together practices and individuals who wish to improve arthritis management. Likewise, Canine Arthritis Management provides information to pet owners and is a great resource for owners to tap into.

Aim.OA is a complete digital disease management assistance system aimed at facilitating arthritis clinics and the delivery of multimodal plans.

All these resources seek to improve the management of OA – a chronic disease which, when effectively managed, can be rewarding and life‑changing for pets, owners and the veterinary team.

References

- Aim.OA (www.aim-oa.com).

- Belshaw Z, Asher L and Dean RS (2016). Systematic review of outcome measures reported in clinical canine osteoarthritis research, Vet Surg 45(4): 480-487.

- Belshaw Z, Robinson NJ, Dean RS and Brennan ML (2018). “I always feel like I have to rush…” pet owner and small animal veterinary surgeons’ reflections on time during preventative healthcare consultations in the United Kingdom, Vet Sci 5(1): 20.

- Brown DC, Boston RC, Coyne JC and Farrar JT (2008). Ability of the Canine Brief Pain Inventory to detect response to treatment in dogs with osteoarthritis, J Am Vet Med Assoc 233(8): 1,278-1,283.

- Canine Arthritis Management (www.caninearthritis.co.uk).

- Conzemius MG and Evans RB (2012). Caregiver placebo effect for dogs with lameness from osteoarthritis, J Am Vet Med Assoc 241(10): 1,314-1,319.

- Hielm-Björkman AK, Kuusela E, Liman A, Markkola A, Saarto E, Huttunen P, Leppäluoto J, Tulamo R and Raekallio MR (2003). Evaluation of methods for assessment of pain associated with chronic osteoarthritis in dogs, J Am Vet Med Assoc 222(11): 1,552-1,558.

- Reid J, Wright A, Gober M, Nolan AM, Noble C and Scott EM (2018). Measuring chronic pain in osteoarthritic dogs treated long‑term with carprofen, through its impact on health-related quality of life (HRQL), Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 31(S 01): A1-A6

- Väre P, Nikiphorou E, Hannonen P and Sokka T (2016). Delivering a one‑stop, integrated, and patient‑centered service for patients with rheumatic diseases, SAGE Open Med 4: 1-7.

- Veterinary OA Alliance (www.vet-oa.com).

- Veterinary Record (2018). Caring for a dog with osteoarthritis, Vet Rec 182(15): 440.

- Walton MB, Cowderoy E, Lascelles D and Innes JF (2013). Evaluation of construct and criterion validity for the ‘Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs’ (LOAD) clinical metrology instrument and comparison to two other instruments, PLOS One 8(3): e58125.