22 May 2020

Management of OA part 2: plan for life

Ross Allan and Stuart Carmichael continue their advocation of having dedicated teams for this issue by discussing the importance of addressing both an immediate and long-term strategy.

In part one of this article, the authors advocated the creation of dedicated OA teams that could not only assess the problem, but also progress and deliver multimodal solutions.

It is well recognised that multimodal plans better address the complexity of the disease and can be modified appropriately as the needs of the patient change with time. With this in mind, any plan should not only address the immediate needs of the problem, but also look ahead to more long-term considerations.

When developing this management strategy, a number of key components exist:

- create a plan to meet OA objectives using a multimodal system

- “on-board” the owner

- agree a long-term strategy and a way it will be delivered

Create a plan: choose management options based on defined objectives

In any clinical problem it is good practice to identify the key issues, which often are multiple, and decide how to deal with them. In OA management, clear objectives that can be addressed by the plan should be established at the time of the initial patient assessment.

The management plan developed must seek to target the priority objectives and outline a practical plan that will enable your patient to meet them. The plan must also decide when patient review should occur and what “success” would be at the time of the patient review.

Planning needs a structure. The essential targets of the multimodal approach are recognised as pain, diet and exercise (Fox, 2010).

With an OA patient management tool, these key targets have been expanded to allow them to be better incorporated into a workable plan, with six key targets:

- A – Analgesia

- B – Bodyweight and diet

- C – Client and environment

- D – Disease

- E – Exercise

- F – Follow-up

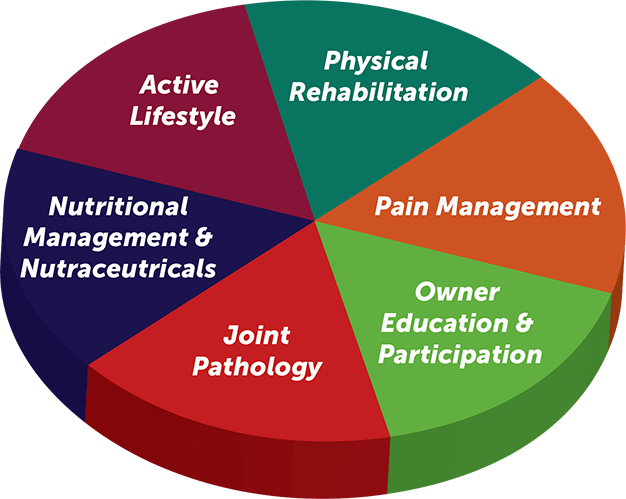

This can also be represented diagrammatically by another modified system where owner education and participation is highlighted along with physical rehabilitation, but the overall objective is essentially the same (Figure 1).

Clearly identifying objectives of each individual case can help select the correct management interactions and plan for that patient/owner combination. This makes it easier to navigate the large number of options available (Tables 1 and 2).

| Table 1. Pain management options | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Agent | Example | Action | Objective/use |

| Local/ peripheral |

NSAID (non-selective) | Carprofen Meloxicam |

Anti-inflammatory Prostaglandin (PG) inhibition |

Acute flares General analgesia |

| NSAID (cyclooxygenase [COX]-2 selective) | Mavacoxib | Extended action | ||

| Cimicoxib Firocoxib Robenacoxib |

Selective COX-2 action | If gastrointestinal toxicity concerns | ||

| PG receptor antagonist | Grapiprant | EP4 receptor antagonist | If gastrointestinal toxicity concerns | |

| Monoclonal antibody | Ranevetmab | Anti-nerve growth factor monoclonal antibodies | Different approach | |

| Peripheral | Acupuncture | Neuropeptide release | Alternative solution | |

| Centrally acting (adjunctives) | Paracetamol Codeine |

Central PG inhibition Opiod (mu) agonist |

Supplementary rather than replacement choices | |

| Amantadine Gabapentin |

N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid antagonist Calcium channel blocker |

Sensitisation | ||

| Table 2. Management options | ||

|---|---|---|

| Domain | Therapeutic objectives | Options |

| Active lifestyle | Regular activity avoiding excess Environmental optimisation |

Exercise plans CAM home checklist |

| Physical rehabilitation | Ensure affected joints retain maximum mobility Protect supporting soft tissue structures and muscle bulk Positive biological and pain-relieving actions |

Passive ROM exercises Physical therapy by a trained therapist Hydrotherapy (treadmill, pool) Modalities (laser, ultrasound, shockwave) |

| Pain control | Minimise obvious pain and discomfort Address chronic pain Facilitate mobility Maintain minimum pain state |

Medical therapy (see Table 1) Acupuncture |

| Joint pathology | Alter intra-articular pathology and progression Disease modification |

Biological or regenerative therapies (MSC, BMAC, PRP, ACS) Other intra-articular therapies (PAAG) PSGAGs |

| Nutritional management and nutraceuticals | Attain a lean bodyweight, body condition score 5/9 Address overweight or obesityFunctional foodsSupplements |

Weight control programme Weight loss dietsEPA foodsEPA ; UC-II Green-lipped mussel extract ASUs; glucosamine/chondroitin preps |

| Owner education and participation | Get understanding of the importance and severity of OA Participate in lifelong management Replace “Dr Google” as the main information provider Measure progress |

Enrolment in support schemes/OA management platforms Special OA clinics OA owner clubs; use sites (VOA, CAM) Use CMIs and share progress data |

| CAM = Canine Arthritis Management, ROM = range of movement, MSC = mesenchymal stem cells, BMAC = bone marrow aspirate concentrate, PRP = platelet rich plasma, ACS = autologous conditioned serum, PAAG = polyacrylamide gel, PSGAG = polysulphated glycosaminoglycan, EPA = eicosapentaenoic acid, UC-II = undenatured type-two collagen, ASU = avocado soybean unsaponifiables, VOA = Veterinary Osteoarthritis Alliance, CMI = clinical metrology instrument. | ||

One of the frustrating and paradoxically good things about managing OA is no single correct way exists to achieve this – different options are available. A practice should decide which of the different options it prefers to use and create a “toolbox” of skills and techniques/options it can offer, to enable it to cover each of the areas outlined in Figure 1. The authors suggest this structured approach would enable the practice to address most OA presentations.

It is important when making any adjustments to the OA management plan to first review the patient’s progress against the initial objectives. This logical step-by-step approach is appreciated by owners, and must be shared with them so they fully understand and can be empowered to contribute to discussions on possible changes in their pet’s OA management plan.

Owner ‘on-boarding’

Owner involvement is crucial to the success of treating pets with OA, and the process and importance of “on-boarding” the owner should not be underestimated.

For example, this owner wrote: “My black Labrador retriever was six years old when she was diagnosed with arthritis following an acute shoulder sprain. I was stunned. My healthy, energetic dog was now facing a painful, chronic and degenerative disease that would be with her for the rest of her life” (Veterinary Record, 2018).

While perhaps not entirely incorrect, this depressing and unhelpful interpretation of OA is a poor starting point for OA patients. It is, however, all too often the impression of OA that many owners get following their pet’s OA diagnosis.

This is a failure of us as clinicians to emphasise the dynamic nature of OA, and a failure to use the “magic moment” that presents at the time of diagnosis to carefully deliver a message that will create a platform for effective ongoing client and patient management.

The authors would not suggest this is deliberate – it fits with the traditional “diagnosis and treatment” approach that underpins our teaching as veterinary professionals. They would, however, suggest the priorities that require consideration when managing chronic disease, and the owners whose pets have it, are different and need taking into account when discussing chronic disease management.

For this reason, in the authors’ opinion, a key element of the OA “day zero” message should be the cautious optimism that, in the vast majority of patients, simple medical and non‑medical/lifestyle treatments can be used that can effectively help the vast majority of patients with OA.

This emphasis – contrasting with “here’s the painkillers, now off you go” message – is an essential one. Emphasising that treatment is not all dependent on medicines, the dynamic nature of OA and importance of proactively assessing the response to treatment is an absolutely vital part of successfully treating each and every pet with OA.

When clients are given the opportunity to “learn” the dynamic nature of OA and given a structure (such as OA clinics, mentioned in part one) that facilitates this inquisitiveness, they will grasp the opportunity to manage their pet’s OA alongside the clinical team – not separate from it.

This is the “epiphany” that the clinical team (not just vets) needs to strive for: clients not only wishing, but actively demanding to see their pet’s progress and look for the rational, evidence-based medicine advice to support their pet’s chronic disease management.

Agree a strategy and how it will be delivered

So, clear identification of the exact concerns noted by the owner at the outset (and at each review) is critical to this process. These concerns adjust the way the key management objectives are identified, and how they are going to be addressed and monitored.

Doing this, and being mindful of the part the owner will play in achieving the first set of objectives, is a key part of successful OA management.

Case study

Signalment

Susie, an 11-year-old female, neutered cocker spaniel.

History

Susie was referred for management of her OA with an eight-month history of forelimb lameness. She had been initially treated with NSAIDs, and latterly NSAIDs in conjunction with tramadol. No diagnostics had been performed during this time, and Susie’s referral occurred since “doggy day care says she is limping more and is in pain” (Figure 2).

Exam and diagnostics

Susie had a 6/10 left forelimb lameness, with muscle atrophy of the left shoulder. The left elbow was mild‑moderate thickened and had 20° reduced range of motion (ROM). The right elbow was mildly thickened. X-rays taken showed moderate OA of both elbows and blood samples were unremarkable.

Problem list

Susie’s elbow OA caused her the following problems:

- pain

- restriction to elbow ROM

- muscle atrophy

OA management plan

When treating Susie’s OA, the focus was placed on the problems identified – not only pain relief.

Key points

• When OA is confirmed, you can – in general – disregard the radiographic changes

• Focus your management choices on what you can change and influence

• Remember that OA is a dynamic disease

Active lifestyle

While Susie’s home life could have appeared simple – “she lived in a flat and was not too active, given her age” – this would be an incorrect interpretation of what could be changed to improve her well-being and OA management.

The true significance of Susie’s bed was clear when a video from her owners was reviewed. This showed the difficulty Susie had getting up, over and out of her egg-shaped, plastic, high-sided bed. It also showed the wooden floors she had to contend with when out of her bed and jumping down from the sofa. Both of these were things that could be easily improved.

When meeting the owners, Susie’s exercise and other “daily routines” were also discussed. Not much of a specific “purpose” existed to her exercise; direct consideration of the environment or terrain she was walking in. This could be adapted to help her mobility.

Nutrition

As with many dogs we meet, Susie’s owners had worked hard to find a diet that suited her and didn’t cause digestive upset. While “prescription” diets may be better suited to help OA, it was instead decided to measure and moderate her food intake, and maintain her nutraceutical product.

This was also supported by Susie’s body condition score (BCS), which was 5/9.

Owner education and participation

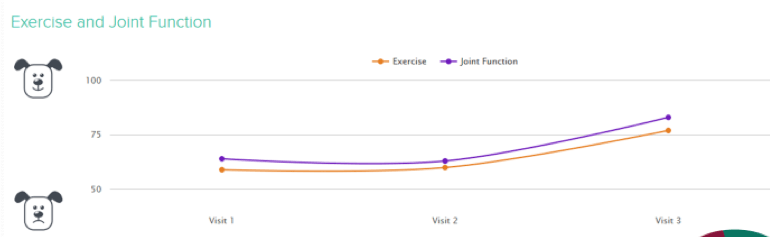

The authors used an OA patient management tool to help assess and score Susie’s OA, to provide a way of measuring whether the changes that had been made actually helped her.

Why use an OA patient management tool to help treat OA?

- “visualise disease”

- “define the strategy”

- “on-board clients in the care plan”

- At the start, Susie’s scores were:

- pain: 30%

- exercise and joint function: 64% and 59%

Pain management

When Susie’s proactive management started, it was decided not to change her pain medication. In the authors’ opinion, changes existed – notably in Susie’s home life and exercise/rehabilitation BCS – which they were confident should improve her pain score without the need for immediate additional medical treatment.

A key element of this decision was that it was planned to review Susie at a predefined time – and had her pain not responded as expected, the need for medical treatment would have been reviewed.

In humans, exercise has been shown to be an effective non-pharmacological intervention that can reduce pain, and improve physical and psychological functions (Ambrose and Golightly, 2015).

In a similar way, the authors would contend that well‑being is a balance between pain and mobility, and some simple home life factors could improve both Susie’s well-being and activity:

- getting her an open bed

- making sure rugs and runners are around

- steps to get up and down from the sofa

Physical rehabilitation

Susie was started on a programme of simple joint mobilisation exercises, which the owners were taught to deliver at home.

These would help improve her joint range of motion and muscle strength, and resultant desire to improve her joint health and function.

The exercises “prescribed” included defining the number of “sets and reps” Susie should do. This meant the programme could be easily adapted during her management, which included rechecks at four and eight weeks (Table 3; Figure 3).

| Table 3. Changes in Susie’s status in the eight weeks following her OA management plan starting | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 weeks | 4 weeks | 8 weeks | |

| Pain | 30 | 30 | 9 |

| Exercise | 59 | 60 | 77 |

| Joint function | 63 | 63 | 83 |

| Weight (kg) | 15 | 14.7 | 15 |

Owner feedback

The regular rechecks of Susie’s progress provided feedback on what her owners felt of their involvement, and the changes they made had helped them understand and follow her progress:

- “She used to jump off the sofa to get down, and you could see her being very tentative at the edge of the sofa before we got the steps.”

- “Susie used to be extremely slow going down the stairs – she would almost hobble down a step at a time and usually go at a very wide angle, which she seemed to find helped her and probably made it less painful. Sometimes we would need to carry her up and down the stairs. Now she is much better.”

- “To get to the river from our flat, it involves going down three flights of stairs from the top of the bridge down to the river. However, we have found a different way to get there, which avoids the stairs and takes her under the bridge.”

- “We learned quite a lot and understand a lot more about OA. It makes more sense now.”

- “We liked having a system, and being able to look back. We are more aware of Susie’s needs and limitations”.

Key points

• Empower owners to effectively manage their pet’s chronic disease

• Aim to measure progress – it will help you

• Regularly and analytically review your patient’s progress – and make decisions; don’t let things drag

• Enjoy managing chronic disease and maximising your patient’s well-being

• Make maximising well-being a key objective of how you care for your patients

• Join your patients on their journey

Conclusion

This case study demonstrates how an OA management plan can be successfully delivered by putting into practice the key points aforementioned and in part one.

OA management plans can be really simple, so long as they are addressing predefined objectives set to improve the clinical status. Repeated assessment and review of progress also places these objectives in a much more realistic timescale, and helps ensure progress is being made.

Taking this proactive approach to OA management is far more clinically rewarding for the veterinary team; refreshing and positive for pet owners; and, most importantly, significantly improves the care provided to our patients.

- Some drugs in this article are used under the cascade.

References

- Ambrose K R and Golightly YM (2015). Physical exercise as non-pharmacological treatment of chronic pain: why and when, Best Practice and Research: Clinical Rheumatology 29(1): 120-130.

- Fox SM (2010). Multimodal management of canine osteoarthritis. In Chronic Pain in Small Animal Medicine (1st edn), Manson Publishing, London: 189-201.

- Palmer RH and Churchill J (2019). The keys to effective osteoarthritis management in small breed dogs, Zoetis, Proceedings from WSAVA Congress 2019, Toronto.

- Veterinary Record (2018). Caring for a dog with osteoarthritis, Veterinary Record 182(15): 440.