12 Aug 2021

Georgina Sharman looks at the use of this in practice and how vet nurses can assist.

Image © zwiebackesser / Adobe Stock

Anaesthesia plays an essential part in the RVN’s role; it is a daily occurrence.

As RVNs, a need to evolve and develop anaesthesia techniques exists, so patient care quality can be improved. The aim of this article is to discuss the role through each step of the anaesthesia process.

For a successful anaesthetic case, whether it be a simple castrate or a complex diaphragmatic hernia, RVNs need to be prepared. Four steps exist in the pre-operative stage before premedication – these are:

Familiarising yourself with the patient history is essential. Granted, for a six-month-old cat spay chances are the history is minimal, with no concerns. However, if you have a 13-year-old diabetic dog with a heart condition, reading up on the history might be a good idea. Ultimately, the veterinary surgeon is in charge and will always make the final decision. However, reading up about the case beforehand will help you be prepared for what to expect in anaesthesia.

Speaking to owners about their pets is necessary before admission. The procedure can be discussed, as well as any concerns the owner has. See Panel 1 for what to look out for in history.

Performing a head-to-toe clinical examination is vital for planning out the anaesthetic and can help improve the RVN’s skill set. While vets do examine patients when they enter the practice, RVNs need to do the same. It helps RVNs to be able to distinguish between normal and abnormal, mainly when listening for heart murmurs. You must ensure to check:

This stage is to help you plan and prep for the general anaesthetic at hand. Firstly, discuss with the veterinary surgeon what drugs will be used for the patient. Even though young, healthy patients are likely to receive the same premedication and sedation protocol, not every patient will receive that protocol.

Plan together with the veterinary surgeon on every patient protocol. Not only will the patients receive a tailored plan, as a veterinary team, but this will also help you gain a better understanding of anaesthesia – particularly the different drug protocols.

Discuss if anything additional is needed for the patient, including – but not limited to – blood work, nail clipping, a regurgitation plan for patients at risk and so on.

Assign an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score for each patient (Table 1) to determine the risk level of anaesthesia and help prepare for this. The ASA score is not dependent on the procedure, but the history and the condition of the patient.

| Table 1. An adapted American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System (ASA, 2020) | ||

|---|---|---|

| ASA | Definition | Examples |

| I | A normal, healthy patient. |

|

| II | A patient with mild systemic disease. |

|

| III | A patient with severe systemic disease. |

|

| IV | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life. |

|

| V | A moribund patient that is not expected to survive without the operation. |

|

Make sure all emergency drugs are worked out for each patient and familiarise yourself with the RECOVER guidelines (RECOVER, 2012). The RECOVER certification is an excellent method for preparing for a CPR situation.

The author’s personal choice is to prepare an anaesthesia tray for every patient (Figure 1). This can include, but is not limited to:

Secondly, breathing system choice. Depending on what your practice has, select the appropriate-sized circuit for the patient. All circuits and ETTs must be checked before starting every case, especially for any leaks or concerns with the anaesthetic machine.

Ensure all patients undergoing anaesthesia or sedation have an IV catheter in place, even if this is a minor procedure. This is because an emergency can occur at any time, no matter the procedure. This can be placed by RVNs whenever deemed appropriate, ideally before premedication.

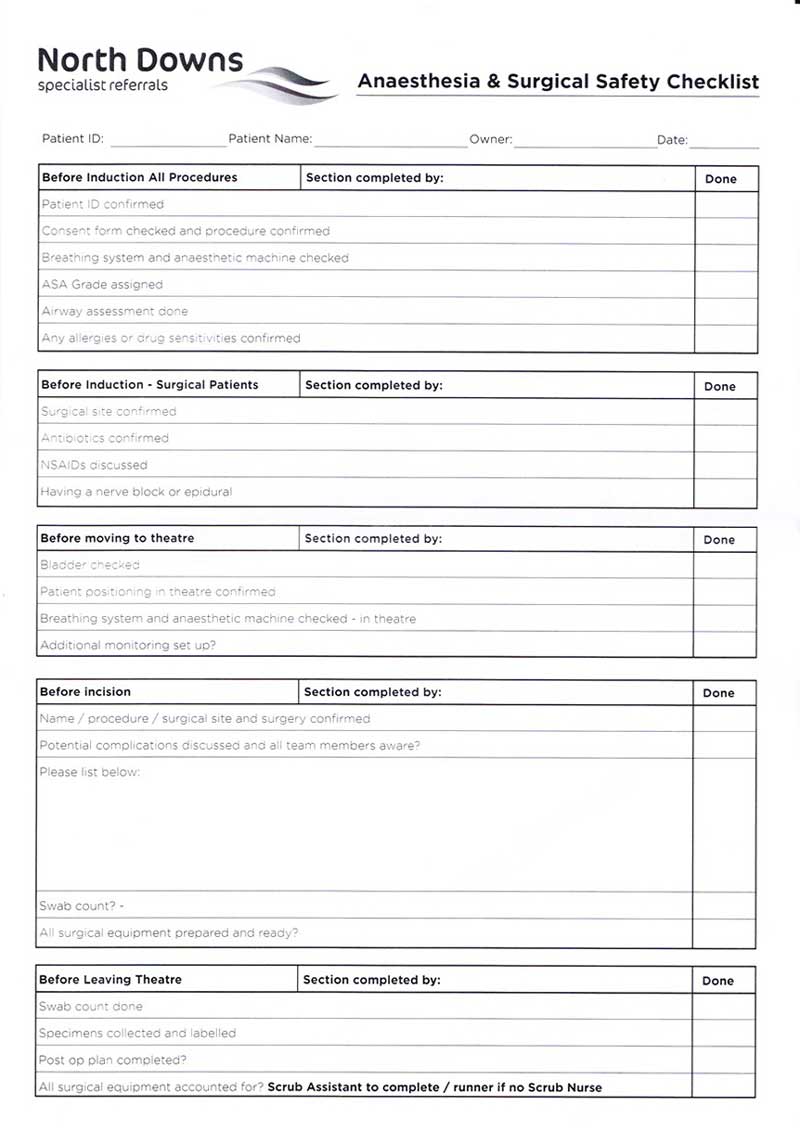

All patients need to have an anaesthetic or surgical checklist. This is to avoid mistakes that might occur and this is the final check before the induction of a patient (McMillan, 2014). See Figure 2 for an example of a checklist.

Monitoring starts from the administration of premedication. A vigilant eye is always kept on the patient. Knowing the importance of how different drugs react and act on the patient, and the various systems is a must.

Pre-oxygenation is recommended before induction, ideally with a face mask rather than flow-by (Wong et al, 2019). This will improve the oxygen content for the patient, especially patients with difficult airways.

Although a veterinary surgeon performs induction as per the RCVS guidelines (RCVS, 2021), intubation can be performed by the VN. This needs to be performed with a laryngoscope to visualise the airway better and detect any abnormalities with the airway.

Opioids are used for every anaesthetic or sedation case. The choice of opioid depends on the severity of pain.

Methadone is the primary choice for moderate or severe pain. Buprenorphine is helpful for mild to moderate pain; however, this has a “ceiling effect” and cannot be topped up to increase the level of analgesia. Butorphanol is helpful for mild pain and sedation only. Opioids must not be wholly relied on.

A multimodal approach is essential for surgery cases. NSAIDs and paracetamol can be used to reduce pain. Constant rate infusions can also be used for patients to provide continuous analgesia, such as ketamine, lidocaine, fentanyl and medetomidine.

RVNs can be used to learn and use local and regional nerve blocks to better patient welfare, and reduce the need for inhalant anaesthesia or additional pain relief (Grubb and Lobprise, 2020). The placement of a diffusion catheter and chest drains in specific surgical sites can enable RVNs to give local anaesthesia to the surgical site.

Record keeping is necessary. Ideally, one nurse needs to be monitoring the patient, and circulating and preparing the patient; however, that is not always ideal. It is essential to watch for trends and be as accurate with your record-keeping as you can.

Regular eye lubrication is crucial for the prevention of corneal ulceration (Dawson and Sanchez, 2016). This needs to be from the start of anaesthesia and continued until 24 hours after anaesthesia due to the reduced tear production caused by anaesthesia.

Patients need to keep warm under anaesthesia. Anaesthesia decreases the temperature and can do so dramatically with small patients, or if the surgical site is the thorax or abdomen (Druce, 2015). This can be due to various reasons such as drug-induced vasodilation, high surface area and depressed homeostatic mechanisms.

Two methods of patient warming exist: passive warming and active warming. Passive warming examples include:

Active warming includes:

First and foremost, the most critical monitoring aspect is you, the RVN or SVN. Even though practices are becoming more technologically advanced with monitoring equipment and multiparameter monitors, these do not replace the most critical aspect.

You can help make clinical decisions, troubleshoot and inform the veterinary surgeon if anything is wrong.

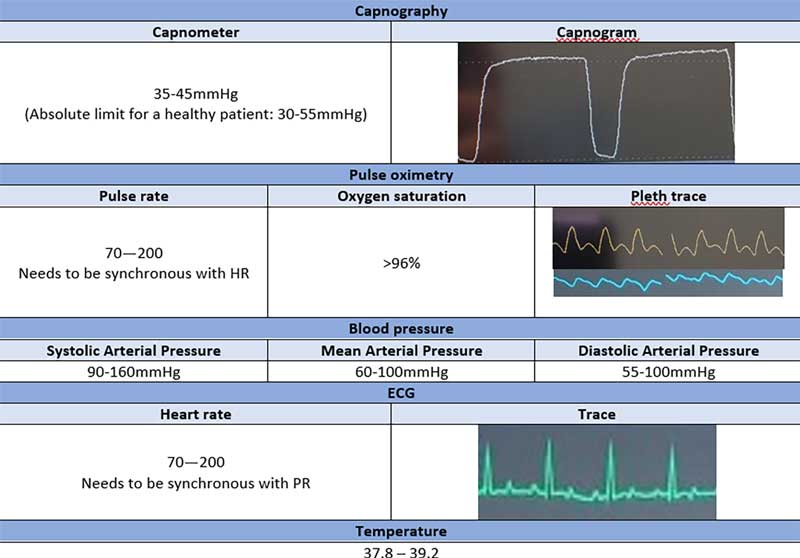

As an RVN, you monitor the patient’s neurological aspects; this includes the palpebral reflex, pinch reflex and eye rotation. With gold-standard monitoring, monitoring equipment or a multiparameter is necessary (Figure 3).

Capnography relies on the amount of expired carbon dioxide in respiration. This measures the numerical amount at the peak (capnometer) and visualises the waveform (capnogram). This is measured using mainstream or sidestream monitoring, and the device needs to be placed between the ETT and the breathing system.

Pulse oximetry measures pulse rate and oxygen saturation using an infrared probe.

The probe can be placed on either the tongue, ear, digits, prepuce, vulva or skin. Placing a white gauze swab around the tongue can improve contact.

Non-invasive blood pressure is the blood pressure measurement using a blood pressure cuff. This can be measured using an oscillometric device or the Doppler.

ECG is the measurement of the electrical activity of the heart. This can be done by placing ECG pads or crocodile clips; by having two on the forelimbs and two on the hindlimbs.

Ensure a sufficient amount of ultrasound gel or surgical spirit on the ECG pads or crocodile clips to get an adequate reading.

The core body temperature must be measured. This can be done by placing a temperature probe in the oesophagus or rectum.

Just because the anaesthetic is finished does not mean the patient is 100% clear from harm. Most anaesthesia-related deaths occur within the postoperative period, so vigilance is still necessary (Brodbelt et al, 2008). These patients must not be left alone.

Use suction and clear the airway before the patient wakes, if necessary – especially in regurgitation cases (Fenner et al, 2019).

Express the bladder, if indicated, to ensure comfort on recovery. Ensure the patient is clean and dry, and has the appropriate dressings.

Prepare what is needed in the recovery area for the patient. This includes heating, drip pumps, additional monitoring and oxygen, if necessary. Have ETTs and an induction agent (such as propofol or alfaxalone) ready for the possibility of airway obstruction.

Ensure the patient is maintaining oxygenation before moving to the recovery area. Continue to keep the patient warm. Resume regular monitoring and record-keeping until the patient is alert, awake and eating. Feed the patient as soon as possible.

Anaesthesia is one of the most prominent aspects of the life of a veterinary nurse. Aiming for best practice is what we all strive for as veterinary nurses.

Communication with the veterinary surgeon is vital. RVNs can achieve so much with anaesthesia through the use of additional qualifications and training.

After anaesthesia cases – especially after complex ones – it is crucial to allow yourself a moment of self-reflection. It is essential to reflect on what was performed well, what was not and how it can be improved on. Performing clinical audits can also enhance the quality of cases.

Georgina Sharman

Job Title