27 Jun 2016

Managing chronic gastrointestinal signs in cats and dogs – part 2

Florence Vessieres and David Walker, in part two of their article, consider enteropathies in identifying the cause of vomiting and diarrhoea, and treatment trials in cases with no definitive diagnosis.

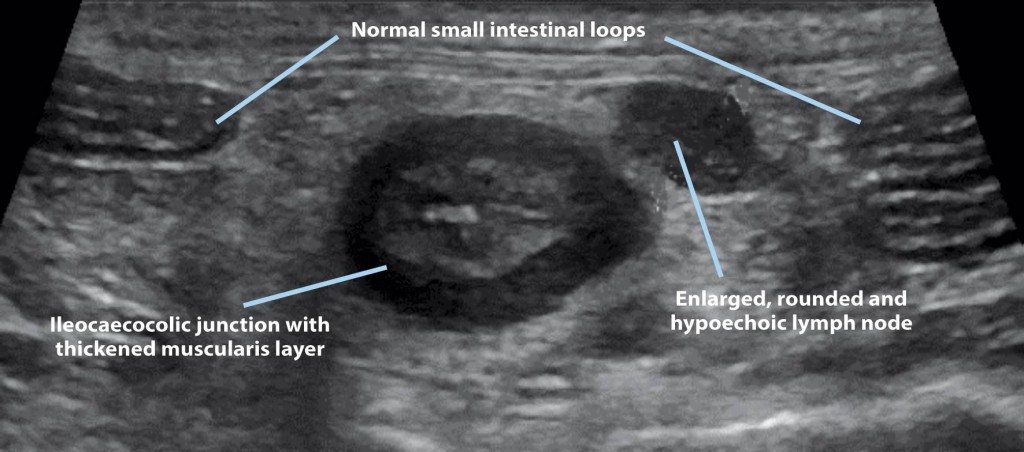

Figure 2. Ultrasonographic view of the ileocaecocolic junction, small intestinal loops and one of the abdominal lymph nodes in a four-year-old cat with alimentary lymphoma. Note the thickened muscularis layer of the junction compared to the layering of a normal small intestinal loop.

Chronic gastrointestinal signs are a common presentation in veterinary medicine and, although uncommonly life threatening, can frustrate owners and veterinary surgeons.

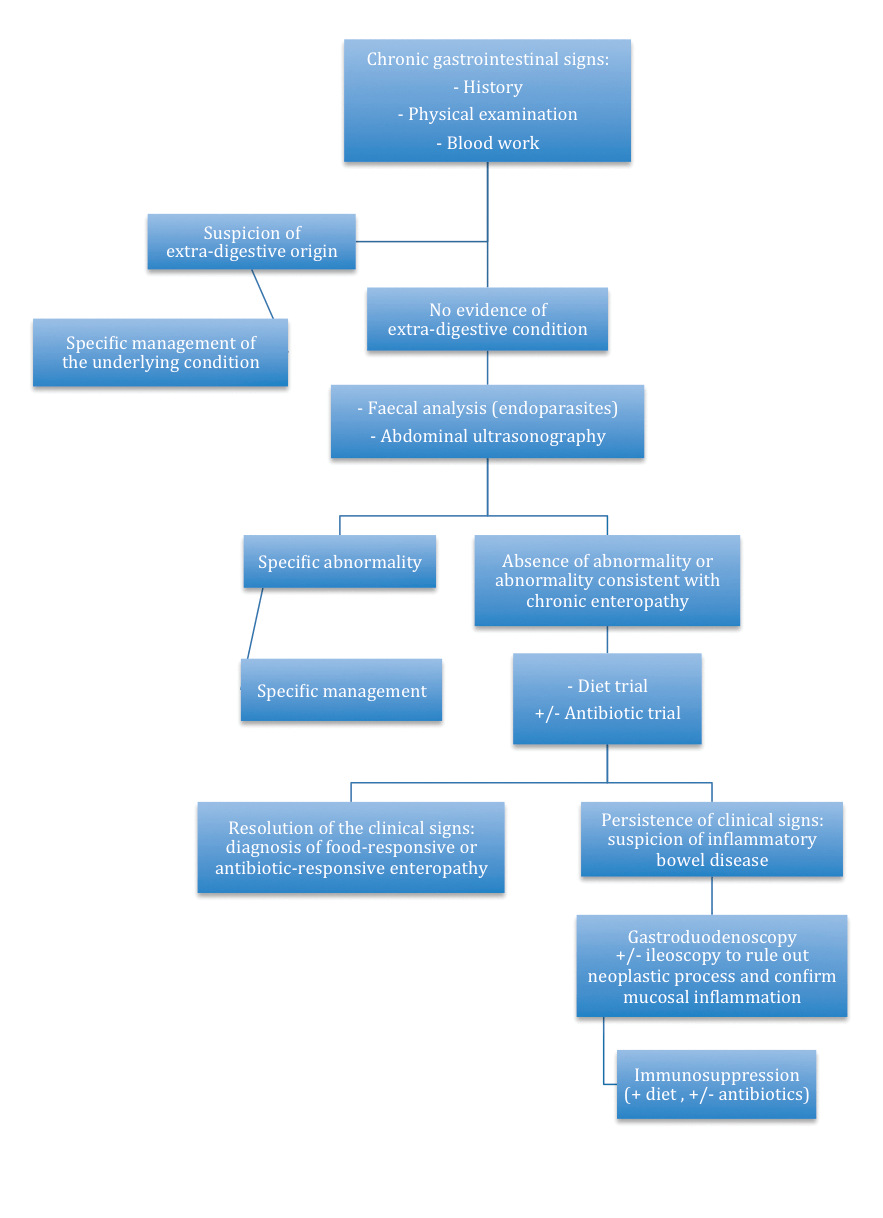

Medical history, physical examination and basic investigation (blood work) will often provide enough information to rule in, or out, an extra-digestive aetiology. Abdominal ultrasonography is then performed to try to identify and/or localise potential lesions, decide if further tests are immediately needed and decide which further diagnostic tests are appropriate. Dietary and antibiotic trials can then be performed if ultrasound does not lead to a definitive diagnosis.

If treatment trials fail, it is recommended gastric and intestinal biopsies are taken to confirm inflammatory bowel disease, or alimentary lymphoma, and initiate appropriate therapy.

This article presents one way of approaching chronic vomiting and diarrhoea in dogs and cats (Figure 1), with a particular focus on chronic enteropathy.

The differential diagnoses for chronic gastrointestinal (GI) signs are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1. Differential diagnoses for acute vomiting and/or diarrhoea in cats and dogs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Digestive | Infectious | • Bacterial: Salmonella, Campylobacter, Clostridium, pathogenic Escherichia coli and Yersinia. • Viral: canine distemper virus, canine parvovirus, feline panleukopenia virus, feline enteric coronavirus, FIV and FeLV. • Parasitic: helminth and protozoan – such as Giardia, Coccidia and Tritrichomonas (cats). |

| Inflammatory | Chronic enteropathy: antibiotic-responsive enteropathy, diet-responsive enteropathy or inflammatory bowel disease. | |

| Neoplastic | Gastric or intestinal tumour: carcinoma, round cell tumour and sarcoma. | |

| Obstructive | • Foreign body and partial/complete obstruction. • Neoplasia. • Intussusception. |

|

| Extra-digestive | • Hepatobiliary disorders. • Pancreatitis, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. • Nephropathy. • Endocrinopathy: hypoadrenocorticism (dogs), hyperthyroidism (cats) and diabetic ketoacidosis. • Reproductive and urinary tract disorders: pyometra, prostatitis and orchitis. • Miscellaneous disorders: CNS disorders and drugs. |

|

Medical history

When taking the clinical history, it is important to get as much information as possible about the vomitus (blood, bile, undigested food, time lapse between the meal and the vomiting episode, and frequency of vomiting) and/or the diarrhoea (melaena, haematochezia, mucus and frequency).

It is also important to differentiate between vomiting and regurgitation, as the differential diagnoses and diagnostic approaches are different between these clinical signs.

Other findings, such as reduced appetite, lethargy, weight loss and polyuria/polydipsia, have to be recorded as they may help to refine the differential diagnosis list and, therefore, the diagnostic approach.

Small intestinal and large intestinal diarrhoea can, sometimes, be difficult to differentiate and often overlap, but some characteristics can help to differentiate between them (Table 2).

| Table 1. Clinical signs in small intestinal and large intestinal diarrhoea | ||

|---|---|---|

| Small intestinal | Large intestinal | |

| Faecal volume | +++ | + |

| Mucus | – | +++ |

| Blood | Melaena | Fresh blood |

| Frequency | + | +++ |

| Tenesmus | – | +++ |

| Dyschezia | – | + |

| Weight loss | ++ | + |

| Vomiting | + | + |

| General condition deterioration | + | – |

| Hypocobalaminaemia | ++ | – |

| Key: – absent; + mild; ++ moderate; +++ severe. | ||

Physical examination

A thorough physical examination should be performed, but particular attention should be paid to body condition score, presence or absence of dehydration, presence or absence of hypovolaemia, pallor or jaundice of the oral mucous membranes, abdominal palpation, rectal examination and rectal temperature.

Ruling out disease of extra-digestive origin

When an animal presents with chronic GI signs, the first step is to exclude an extra-digestive aetiology. This is mainly done on the basis of blood work.

The suspicion of disease of extra-digestive origin will be increased or decreased by:

- haematology

- serum biochemistry – including urea, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, glucose, total solids, albumin and cholesterol

- electrolytes

- basal cortisol in dogs, with or without adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test, as necessary, based on the basal cortisol concentration

- serum cobalamin, with or without canine pancreas-specific lipase (cPL) or feline pancreas-specific lipase

- trypsin-like immunoreactivity

Thyroxine T4 and FeLV/FIV infection also should be assessed when appropriate.

It is important to remember the sensitivity of cPL tests is about 80%, so a negative result does not rule out pancreatitis. On the other hand, a positive result can indicate a certain degree of pancreatic cell injury, but does not rule out underlying conditions, such as chronic enteropathy.

A study of 47 dogs with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) showed about 30% had elevated cPL immunoreactivity1.

Basal cortisol should be used as a screening test for glucocorticoid-deficient hypoadrenocorticism. A concentration greater than 55nmol/L can be used to rule out the disease, but a lower value does not confirm hypoadrenocorticism, so an ACTH stimulation test is necessary2. Specific electrolyte abnormalities (hyperkalaemia and hyponatraemia) can also raise a suspicion for Addison’s disease, but are not present in glucocorticoid-deficient hypoadrenocorticism (known as atypical Addison’s).

Hypocobalaminaemia (lower than 300ng/L) does not indicate the specific cause of the diarrhoea; it is sometimes identified in chronic enteropathy and alimentary lymphoma. Vitamin B12 supplementation (dogs 0.25mg to 1mg SC once weekly for six weeks, then once monthly for four months to six months; cats 0.125mg to 0.25mg SC once weekly for six weeks, then as needed to maintain normal concentrations) is necessary in cases of hypocobalaminaemia, regardless of the origin of the diarrhoea.

Some evidence suggests oral cobalamin supplementation would be effective in normalising serum cobalamin concentrations in dogs with chronic enteropathy3, but more research in this area is needed.

Significant hypoproteinaemia can be due to protein-losing enteropathy (PLE). In the UK, this typically arises secondary to IBD or alimentary lymphoma. In that case, urinalysis, including a urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio, has to be performed to investigate possible protein-losing nephropathy (PLN), and liver function has to be evaluated to strengthen the suspicion of PLE as a cause for hypoalbuminaemia.

Some breeds, such as wheaten terriers, can have concurrent PLE and PLN4. PLE is typically associated with panhypoproteinaemia, as both albumin and globulin are lost through the GI mucosa. PLN and liver dysfunction are usually characterised by hypoalbuminaemia in the face of a normal globulin concentration.

Chronic intestinal bleeding, not witnessed by the client in some cases, can cause hypochromic microcytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis. Possible causes of chronic GI bleeding include gastric erosion or ulceration secondary to IBD, hypoadrenocorticism, neoplasia and high parasite burden.

Investigating GI signs of ‘digestive’ origin

Abdominal ultrasonography

Abdominal radiographs can be useful when surgical disease is suspected, such as foreign bodies, intussusception and septic peritonitis, and abdominal ultrasound is not an option based on available equipment or expertise.

However, radiographs are rarely indicated in cases of chronic GI signs, given significant findings are unlikely. Furthermore, should an abnormality be found on abdominal radiography, abdominal ultrasonography would almost always be necessary to get more precise information or to take samples (fine-needle aspirate or Tru-Cut biopsy).

A prospective study of 87 dogs presented with chronic diarrhoea was performed to evaluate the contribution of abdominal ultrasound in making a diagnosis5. It showed 21% of dogs were diagnosed with gastric or intestinal neoplasia (9% lymphoma), and 61% were “diagnosed” with presumed chronic enteropathy (diet responsive, antibiotic responsive or inflammatory bowel disease). In 32% of these dogs, ultrasound examination was considered vital or beneficial to making the diagnosis, or was associated with additional benefits to case management. Increased diagnostic utility existed in the presence of weight loss and/or palpation of an abdominal or rectal mass.

A study of 142 cats (healthy, diagnosed with alimentary lymphoma or diagnosed with chronic enteropathy) showed 12.5% of healthy cats, 48% of cats with lymphoma and 4% of cats with chronic enteropathy had ultrasonographic thickening of the muscularis propria (Figure 2). Lymphadenopathy was reported in 2% of healthy cats, 47% of cats with lymphoma and 17% of cats with chronic enteropathy. Interestingly, cats with lymphoma did not have significantly more lymphadenopathy than those with chronic enteropathy6.

Abdominal ultrasound is, consequently, mainly used to rule out neoplastic disease in animals with chronic GI signs and to localise the lesion (mainly intestinal wall thickening, loss of layering and lymphadenopathy). This would help dictate the next diagnostics steps, such as fine-needle aspirates, Tru-Cut biopsy, upper GI endoscopy – with, or without, lower GI endoscopy – and endoscopic versus surgical intestinal biopsy.

Faecal sample: parasitology and culture

Faecal endoparasite assessment is important in animals with chronic GI signs, especially when the patient is young or living in a multi-animal household.

Protozoa (Giardia species, Coccidia, Tritrichomonas in cats) and helminths can be detected by direct examination of the faeces, zinc sulphate flotation and/or centrifugation, or PCR.

Sensitivity of these tests is increased if the sample analysed results from the mixture of faeces collected over three days, as the excretion of parasites is often intermittent.

Fenbendazole (50mg/kg orally once a day for three days to five days) is usually recommended in animals with chronic GI signs due to its broad spectrum of activity.

Anthelmintic therapy is commonly not sufficient on its own to resolve clinical signs, but parasitism tends to worsen the clinical signs associated with underlying conditions, such as chronic enteropathy.

Faecal culture is uncommonly recommended for two reasons – bacterial diarrhoea in dogs and cats is uncommon, and the presence of pathogenic bacteria in a canine faecal sample does not necessarily mean this bacteria is causing the clinical signs. However, if immune-suppressed people are in the household and zoonosis is a concern, faecal culture could be performed.

Pathogenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, Clostridium difficile and Clostridium perfringens are the most common bacteria involved in canine bacterial diarrhoea.

Initial treatment trial

When no signs exist of extra-digestive disease or marked clinicopathological abnormalities, such as poor body condition, abnormal abdominal palpation, melaena, hypoalbuminaemia or severe anaemia, and if the patient is otherwise clinically stable, several treatments can be tried. This is generally done in the following order.

However, some owners and vets may prefer to pursue further diagnostics at this stage, such as ultrasonography and/or digestive endoscopy, prior to performing diet or drug trials.

Diet trial

Dietary trials involve changing to a diet that leads to antigenic modification. It can be a hydrolysed diet (single protein source specially processed and broken down in small particles that the immune system cannot recognise as an allergen) or a diet with a single protein source (such as fish, venison and duck).

It is important for the patient to be exclusively fed this new diet for two weeks. Should the clinical signs not respond to this trial, the next step is usually an antibiotic trial7.

Some diets – such as a highly digestible diet, fat-restricted diet and restricted fibre diet – are designed to optimise nutrient assimilation. Although these diets are useful in managing acute GI signs, they are not designed for managing suspected food-responsive enteropathy.

Antibiotic course

Should the diet trial be unsuccessful, an antibiotic trial can be tried while the prescribed diet is continued, as some enteropathies are multifactorial and respond to a combination of antibiotic and diet.

An antibiotic trial typically involves administration of metronidazole 10mg/kg orally twice a day for two weeks to four weeks. Animals probably respond to antibiotics due to intestinal dysbiosis.

Should the patient not respond to these trials, gastroduodenoscopy and/or ileocolonoscopy (depending on the clinical signs) and endoscopic gastric/intestinal mucosal biopsy should be performed. It is generally not recommended to start immunosuppressive drugs, such as prednisolone, without a definitive diagnosis of chronic enteropathy as neoplastic diseases, such as alimentary lymphoma (particularly common in cats), will temporarily respond to steroid therapy and then be challenging to diagnose once treatment has been started.

Steroid therapy without a definitive diagnosis of chronic enteropathy should only be initiated if digestive endoscopy is contraindicated due to high risk of anaesthesia or financial concern.

Digestive endoscopy

Investigation of chronic vomiting and/or small intestinal diarrhoea (Table 2) would require gastroduodenoscopy, whereas investigation of large bowel diarrhoea would require colonoscopy.

Ileal samples can be obtained in most cases through lower digestive endoscopy, as long as the patient has been adequately prepared; 48 hours of fasting and oral administration of a bowel cleansing solution is required.

The main aim of endoscopy is to obtain GI mucosal biopsies, although focal areas of ulceration or masses that had not been identified by ultrasound can sometimes be detected. Lymphangiectasia can sometimes be grossly visible endoscopically.

Endoscopic biopsies are generally considered favourable to surgical biopsies; however, when the lesions identified on ultrasound are located in part of the intestine inaccessible via endoscopy (mainly distal duodenum, jejunum and proximal ileum), or if the layer mainly affected is not the mucosa (for example, in cases of muscularis layer thickening in cats), surgical full-thickness biopsies are recommended.

This procedure is associated with increased risk (wound breakdown and septic peritonitis, especially in hypoalbuminaemic patients), but is sometimes the only way to obtain a definitive diagnosis – especially in feline alimentary lymphoma – as the most common sites of alimentary tract lymphosarcoma in cats are the jejunum and ileum.

In a prospective study of 10 cats diagnosed with alimentary lymphoma based on full-thickness biopsy sampling, 3 were diagnosed with lymphosarcoma based only on endoscopic biopsy, while 3 were suspected to have lymphosarcoma based on endoscopic biopsy, meaning endoscopic biopsy led to an incorrect diagnosis of IBD in 40% of cats with small intestinal lymphosarcoma8.

In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, PCR for antigen receptor gene rearrangement (clonality assay) can help detect a clonal lymphocyte population and, therefore, increase the suspicion of lymphoma.

In a study of 29 dogs with alimentary lymphoma, 22 showed monoclonal rearrangement of the lymphocytes in their intestinal biopsies9.

Chronic enteropathies

Different types

Chronic enteropathy broadly refers to food-responsive, antibiotic-responsive and “idiopathic” intestinal inflammation and GI signs.

Once lymphoplasmacytic inflammation has been confirmed with histopathology of mucosal biopsies, a treatment trial (diet and antibiotic trial, as aforementioned) is initiated if this has not been performed prior to endoscopy.

Inflammatory bowel disease

IBD is defined by:

- chronic (greater than three weeks), persistent or recurrent GI signs

- histopathological evidence of mucosal inflammation

- inability to document other causes of GI inflammation

- inadequate response to dietary, antibiotic and anthelmintic therapies alone

- clinical response to anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive agents10

It is, therefore, important to understand IBD is distinguished from food-responsive and antibiotic-responsive enteropathy not by the histopathological findings, but by the therapeutic response to immunosuppressive agents and not to dietary and/or antibiotic therapy alone.

The underlying cause of IBD remains unknown, but, in humans, different forms of IBD are thought to arise as a result of a host response to intestinal bacteria. Evidence to support this includes the involvement of non-pathogenic bacteria in the development of colitis in genetically altered animals, knowledge the gene associated with Crohn’s disease (form of IBD in humans) is an intracellular receptor for bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan, and the common presence of circulating antibacterial antibodies in people with Crohn’s11,12.

New findings in chronic enteropathies in dogs and cats suggest a pathogenesis similar to that in humans with IBD. Studies have detected imbalances in expression of innate immunity receptors (so-called toll-like receptors) in the intestines of dogs with IBD similar to those seen in humans with IBD. The expression of some of these receptors has been correlated with the severity of clinical disease in dogs with IBD, which makes it likely they are causally implicated in the pathogenesis. In addition, imbalances in the microbiome (so-called dysbiosis) have been identified using molecular methods in dogs and cats with IBD.

In human and veterinary medicine, studies are still investigating whether an abnormal host response to “commensal” bacteria exists, or whether the bacteria have pathogenic features. Genetic predispositions are recognised in several breeds, including Siamese cats, German shepherd dogs, basenjis, soft-coated wheaten terriers and Shar Peis7.

When diet and antibiotics alone are not enough to improve the clinical signs and IBD is suspected, immunosuppressive treatment has to be initiated. Although hypoallergenic diet or novel protein diet is uniformly recommended in the literature in the management of IBD, no consensus exists with regards to the use of antibiotics in IBD.

Some authors recommend a temporary metronidazole course (as aforementioned) with immunosuppressive medication, although a prospective study did not show any significant difference in the remission rate between dogs receiving steroids alone versus steroid and metronidazole for induction therapy of IBD13.

The usual treatment of dogs and cats with IBD consists of administration of immunosuppressive doses of steroids, with prednisolone at 2mg/kg orally once daily for at least 10 days, gradually tapered every 4 weeks by 25% to 50%7.

Side effects of glucocorticoids may be marked at such a high dose, especially in large dogs. If clinical signs do not improve after the first three weeks to four weeks of treatment, or if prednisolone is contraindicated (for example, with cardiac disease or diabetes mellitus) or associated with severe side effects, a second immunosuppressive drug can be introduced.

In cats, chlorambucil is recommended at 2mg/m2 to 6mg/m2 orally once daily14, with regular monitoring of haematology parameters as the drug can be myelosuppressive.

In dogs, ciclosporin (5mg/kg orally twice daily) has been recommended as a second immunosuppressive drug. A prospective study evaluating 14 dogs with steroid-refractory IBD showed improvement of clinical signs in 12 of 14 dogs after a 10-week course of ciclosporin15. If ciclosporin is too expensive, especially in the treatment of large dogs, azathioprine can be considered, although close monitoring is important as this drug can cause hepatotoxicity and pancreatitis.

Protein-losing enteropathy

PLE is a complex group of enteropathies associated with loss of albumin and other proteins across the GI mucosa. The main causes for PLE are IBD, lymphangiectasia or intestinal neoplasia.

The aforementioned diagnostic and treatment steps are to be followed in cases of PLE, but additional specific management is necessary.

Dogs with lymphangiectasia should receive a highly digestible diet with more than 25% of proteins and less than 10% of fat7. Evidence of ongoing and concurrent IBD will dictate the need for novel protein.

Anticoagulant therapy may be indicated (aspirin 0.5mg/kg orally once daily or clopidogrel 2mg/kg to 4mg/kg orally once daily) as hypercoagulability is one of the most important complications of PLE and can lead to thrombus formation.

Thorough work-up is paramount in managing chronic GI signs. Owners have to be aware it can be difficult to find a diagnosis and further investigations are often necessary. Owners also have to be involved in managing the disease as this is likely to increase the chances of therapeutic success.

- Some drugs listed are used under the cascade.