11 Nov 2025

Fergus Allerton BSc, BVSc, CertSAM, DipECVIM-CA, FRCVS previews his session at London Vet Show promising important take-home actions for vets to reduce antimicrobial resistance.

Image: Issara/ Adobe Stock

Any and all antibiotic administration should be rational and in accordance with stewardship principles.

Antibiotic use can cause adverse effects (likely under-reported in veterinary medicine). More importantly, antibiotic use is recognised as a primary driver of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Predictions suggest that human mortality due to AMR could reach 10 million people per year by 20501. These figures seem apocalyptic, but already, a study from 2019 found global deaths in excess of 1.2 million were directly due to multi-drug resistant infections2.

The one health threat from AMR should not be underestimated. All prescribers of antibiotics should ensure that their decision-making balances the individual’s need for medication against the potential exacerbation of AMR. Such deliberation is even more critical when administering antibiotics to animals where no active infectious aetiology is present.

Such use may be described as prophylactic, as it is intended to prevent the development of an infection rather than the treatment of an existing issue. The most common indication for prophylactic antibiotic administration in dogs and cats is for surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis (SAP). SAP accounts for approximately 15% of all antimicrobial use in cats and dogs3, and a very similar proportion (12% to 17%) of inpatient antimicrobial prescriptions in humans4. Ensuring that each prescription is necessary and appropriate is a key principle of antimicrobial stewardship (indeed, this concept represents the P of PROTECT ME).

Surgical site infections (SSIs) have been reported after 0% to 20% of procedures, depending on the type of surgery performed and other patient and procedure factors. SSIs can be classified as superficial (affecting the skin and/or subcutaneous tissues), deep (involvement of the deep soft tissues) or organ/space (involving any part of the body that is opened or manipulated during the procedure other than the skin, fascia or muscle layers).

Clinical severity is often proportionate to the level of infection, with many superficial SSIs readily manageable with topical antiseptic therapy, while organ/space SSIs can represent a life-threatening complication with lasting impacts on the pet’s health (including increased risk of mortality).

SSIs can also impact pet-owner satisfaction, the client-veterinarian relationship and long-term clinician confidence (second victim syndrome). Animals that develop an SSI may subsequently require therapeutic antibiotic therapy to address the infection or surgical revision to debride the site or remove implants to achieve source control.

Preventive measures are routinely adopted to reduce the risk of SSI development, including the rigorous application of the principles of surgical asepsis (use of personal protective equipment, including sterile gloves, hand hygiene and environmental infection control) and, where appropriate, the use of SAP. In human medicine, clinical practice guidelines have been produced to guide SAP for a wide range of different procedures. Recommendations are also incorporated into many veterinary antimicrobial use guidelines5.

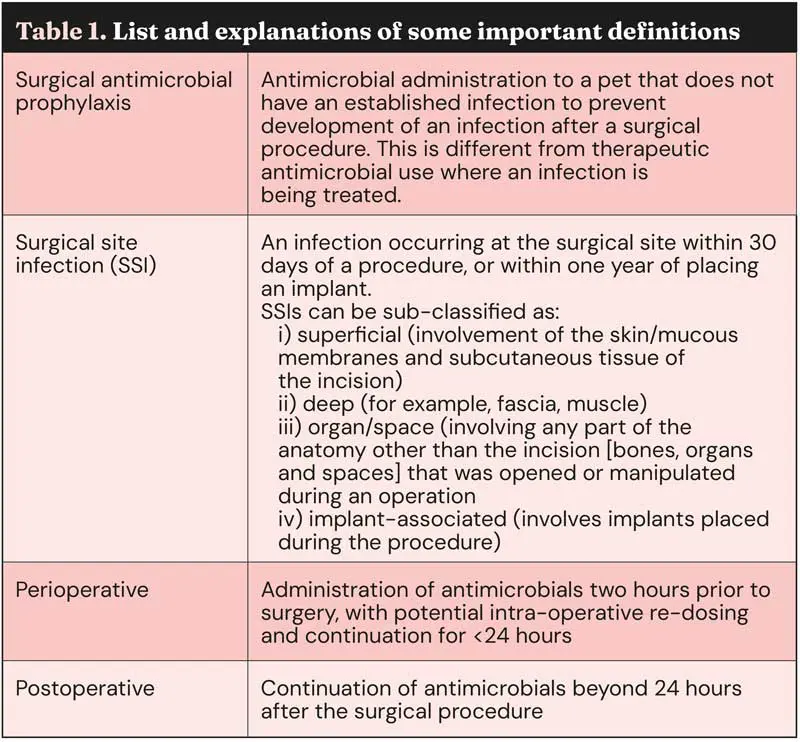

Table 1 features a list and explanation of some of the aforementioned definitions.

The European Network for Optimization of Veterinary Antimicrobial Treatment (ENOVAT) has been developing clinical practice guidelines to support vets to improve their antimicrobial use. A drafting group was created to produce guidelines for surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis. A scoping review has been published6, and evidence-based recommendations are currently under review (publication anticipated late 2025, early 2026).

Limited high-quality data was found comparing the use of SAP in dogs and cats against placebo. Some 34 primary studies, published between 1985 and 2022, including eight randomised controlled trials, were identified. Frustratingly, significant evidence gaps remain in the literature – particularly around soft tissue elective procedures (for example, ovariohysterectomy or castration) or dental extractions, even though these are among the most performed procedures in veterinary practices around the world.

Robust studies with standardised data collection and clear SSI definitions are needed to help generate better evidence to support the guidelines.

Administration of perioperative SAP may be recommended for certain high-risk procedures (for example, those involving entry into the intestinal tract or placement of a surgical implant). However, continuing prophylactic use beyond 24 hours after the end of the procedure (postoperative SAP) is much harder to defend from a mechanistic perspective (wound closure will have already been completed).

The ENOVAT guidelines include strong and conditional recommendations based on the GRADE system of evidence. Strong recommendations include that no SAP (neither perioperative nor postoperative) should be used for clean, soft tissue procedures or for clean orthopaedic procedures that do not involve the placement of an implant. Radius/ulnar fracture repairs performed have been performed without any SAP, with a reported SSI rate of just 3.1%7 and hemilaminectomies were performed with no SAP and SSI rates less than 2%8,9. These findings should reassure surgeons that such orthopaedic procedures can be safely performed without SAP.

The use of perioperative SAP only is conditionally recommended for some clean-contaminated procedures where entry into the gastrointestinal tract is controlled (for example, an enterotomy or enterectomy). Such procedures may incur a greater exposure to commensal bacteria present at the surgical site.

However, data demonstrating a significant benefit from SAP is lacking. The lack of data limits the level of confidence associated with recommendations for clean-contaminated surgical procedures.

The most significant recommendation from the ENOVAT guidelines relates to postoperative SAP. ENOVAT recommends withholding postoperative SAP for all clean or clean-contaminated surgical procedures.

This is a bold recommendation and it may take some time before it is adopted by veterinarians – especially those performing orthopaedic procedures that involve the placement of an implant (for example, with a tibial plateau levelling osteotomy). Nonetheless, it is hoped that the new guidance will prompt clinicians to critically evaluate the need for SAP in all their surgical procedures.

Several studies have published information regarding SSI rates where no SAP (neither perioperative nor postoperative) has been used covering both routine elective procedures and even some orthopaedic procedures4.

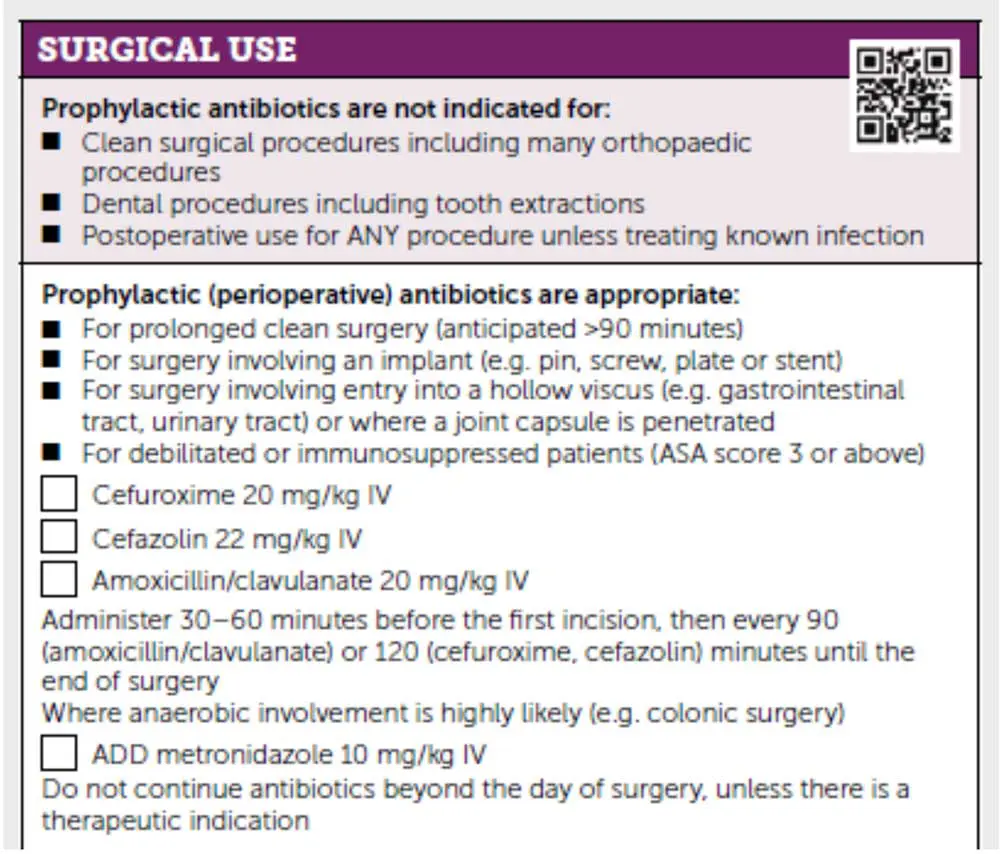

Typically, for clean surgical procedures, an SSI rate of less than 5% is anticipated. Most SSIs observed are categorised as superficial and, therefore, are typically relatively easy to manage. These recommendations have already been included in the PROTECT ME poster (Figure 1).

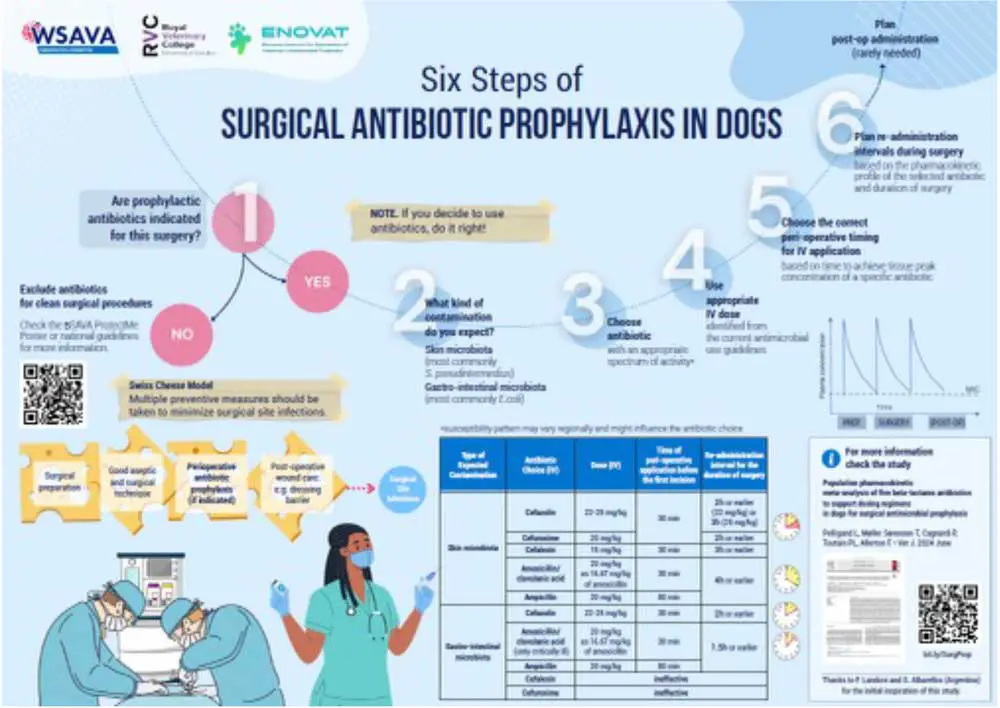

Wherever SAP is deemed necessary, it is important that the antibiotic is administered intravenously between 30 and 60 minutes prior to the first surgical incision.

This timing will ensure that the drug reaches peak concentration (and protective capacity) at the time of greatest need.

Cefazolin (a first-generation cephalosporin) is the most widely recommended drug used for SAP around the world, but in the UK, cefuroxime (a second-generation cephalosporin) is more commonly used. The reasons for this eclectic difference are unclear.

Other potential options include ampicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. A paper last year proposed re-dosing intervals for each of these antimicrobials10 for procedures that are anticipated to take longer than 90 minutes.

A WSAVA infographic that summarises the study findings (Figure 2) is available in multiple languages.

According to the latest guidelines, relatively few surgical procedures really need SAP. Hopefully, new international guidelines can support vets to make appropriate decisions for the animals in their care.

By reducing the use of SAP, the likelihood that an SSI will involve a multi-drug resistant pathogen may also be reduced11, making SSIs that do occur easier to manage.

Strict adherence to Halsted’s principles (gentle handling of tissue, aseptic technique, sharp dissection of tissues, appropriate haemostasis, removal of devitalised tissue and foreign bodies, obliteration of dead space and avoiding tension) when performing any surgical procedure remains the most important step in preventing SSIs.

These measures will help limit our reliance on SAP and reduce the one health dangers from AMR.