7 Apr 2020

Neurological examination of spinal patients, part 1

Simona Radaelli, in the first of a two-part article, analyses owner information to be collected and first steps when examining animals.

Image: Sebastien Behr

Performing and interpreting a neurological examination is a complex task that requires experience and in-depth knowledge of the anatomy, physiology and pathophysiology of the nervous system. Although a thorough neurological examination is required on any patient with a suspected neurological spinal lesion, it is important to know what tests are relevant to localise the lesion within the spinal cord and to determine prognosis.

This article tries to help the general practitioner to perform the key steps of this neurological examination on a patient affected by a spinal lesion. The aim is also to help the clinician in localising the lesion – listing the possible differential diagnoses – and advising the owner on prognosis, and further investigations and possible surgical options.

The article is divided in to two parts. The first part analyses the key information that needs to be collected from owners and explains the first steps of the neurological examination (behaviour and mental status, posture, gait and postural reactions). The second part describes the key spinal reflexes, helps in localising the lesion, and examines how to properly assess nociception while also giving advice on prognosis depending on the neurological findings and their progression.

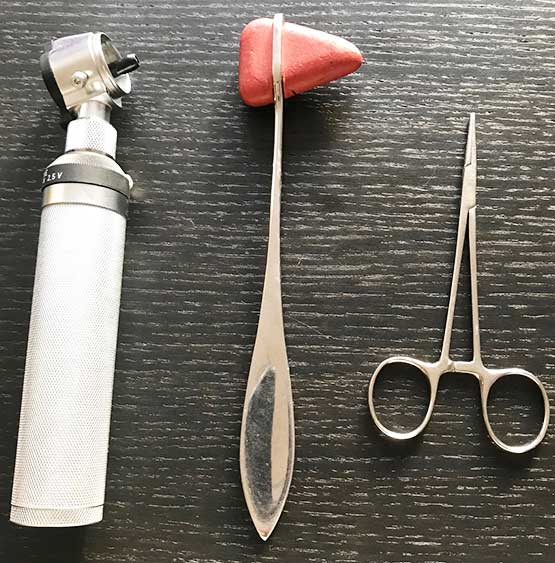

To perform a complete neurological examination, the clinician will need to ensure he or she has the following tools (Figure 1):

- a rubber hammer

- a haemostat

- a strong light source

- a cotton-tipped applicator

Signalment and history

Before performing the neurological examination, it is important to collect the relevant history and signalment of the patient.

A known breed predilection exists for certain types of diseases (intervertebral disc disease in chondrodystrophic breeds, arachnoid diverticula in brachycephalic breeds and Chiari-like malformation in cavalier King Charles spaniels), but any neurological condition could affect any breed.

Age at onset is important in the differential diagnosis as, in general, neoplasia is more common in older animals and congenital disorders in younger patients. Gender predisposition is rarely encountered in spinal diseases.

It is important to collect an accurate history from the owners – onset, progression, presence of pain, abnormal postures, and response to analgesia and anti-inflammatories are all key questions to ask the owner.

For example, a patient with peracute onset of lateralised neurological spinal signs (hemiparesis) – often during exercise, non‑progressive, and without pain response on palpation and manipulation of the spine – could have suffered from a vascular accident (fibrocartilaginous thromboembolism) or a type‑three non-compressive intervertebral disc disease (low volume, high velocity).

The information on the onset and progression of the clinical signs is very important as the hemiparesis could have been caused by any spinal disease, and the absence of pain on palpation and manipulation of the spine is very relevant, but the dog’s temperament and fear in the consult room could sometimes account for the lack of appropriate reaction.

If the clinical signs are intermittent and absent during the consultation, or difficult to evaluate (for example, mild gait abnormality – especially in cats), it is recommended to ask the owner to video record them.

Neurologists commonly use the VITAMIN D acronym to list the possible aetiologies of a neurological disease and a specific time graph to differentiate them, based on onset and progression of clinical signs (Figure 2).

The duration of the clinical signs is very important in spinal patients – especially when evaluating deep pain perception. For example, the longer a plegic patient has had absent nociception, the lower the chances are to recover function of the limb(s).

Dewei and Da Costa (2015) listed common questions that should be asked to owners of patients with a suspected spinal disease (Panel 1).

- What is the problem (present complaint)?

- When did you first observe the signs?

- Which limb(s) is/are affected?

- Did the signs appear quickly or slowly (acute or chronic)?

- Are the signs progressing?

- Do you think the patient is in pain? If so, where?

- If yes, why do you think the patient is in pain?

- Any possibility of trauma? How?

- Has the patient had any similar episodes?

- Are you giving the patient any medicine for this problem?

Neurological examination

A general physical examination always needs to be performed before the neurological examination. The major aims of the neurological examination are to:

- determine whether the clinical signs refer to a disease affecting the nervous system (is it neurological?)

- localise the area of the nervous system affected

- list differential diagnoses

- determine severity and prognosis (when possible)

The neurological examination can be divided into the following key steps:

- behaviour and mental status

- posture

- gait and postural reactions

- palpation

- pain perception

- spinal reflexes

- cranial nerves

A systematic approach to the neurological examination is very useful to standardise the technique and compare findings. Each case needs to be treated differently and, in some circumstances, it is best to perform the tests that are more relevant or less painful to the patients (especially when examining cats, as they are less tolerant towards being handled and restrained), or to avoid tests that may aggravate the animal’s conditions (postural reactions and gait evaluation in a patient with a suspected spinal fracture).

The owners often benefit from explanation of the tests while they are being performed and why, as often they are very nervous about their animal’s conditions and certain tests (such as nasal sensation, cutaneous trunci reflex or nociception) require performing unpleasant actions to the animals.

The spinal cord is divided into four regions, which include segments that have the same predictable and specific neurological signs, and the same abnormalities on the neurological examination:

- C1-C5

- C6-T2

- T3-L3

- L4-S1 (S3)

Multifocal or diffuse lesions could affect more than one segment, or animals can have two or more lesions affecting different parts of the spinal cord.

Behaviour and mental status

While collecting the history of the patient, it is always useful to let the animal walk free in the room – so it is recommended to let dogs free to sniff around, and to open cats’ carriers (placed on the floor) to let them come out of it and investigate the room.

This will give already a good idea of the behaviour and mental status of the animal. More information of this could be also collected from the owners. Animals with spinal disorders should show normal behaviour or mental status, unless they are in discomfort.

Posture

Posture is the position of the body when standing or sitting. In patients with spinal lesions, abnormal spinal postures can include scoliosis (often due to congenital disorders or Chiari-like malformations), kyphosis (if painful thoracolumbar lesions) or lordosis (related to weakness of the epaxial muscles).

Abnormal limb postures, such as plantigrade or palmigrade, are often related to musculoskeletal disorders or polyneuropathies.

In acute thoracic and cranial lumbar spinal cord lesions, Schiff-Sherrington posture may be observed. It is characterised by an extensor hypertonia of the forelimbs and a flaccid paralysis of the hindlimbs. The forelimbs have normal conscious proprioception and voluntary movements.

This posture is often observed immediately after an acute severe lesion of the thoracolumbar spinal cord, but it does not have prognostic factor. The patient is often in lateral recumbency, despite having a thoracolumbar lesion (Figure 2).

Gait

Gait should be examined in the consult room while collecting the history, leaving the animal free to move around, and walking on a lead, ideally outside on a non-slippery surface. It is useful to observe the animal from the front, the back and the side to be able to identify subtle changes in the gait. Comparing the strides on the left and right side of the body allows to identify lateralised abnormalities.

The gait is generated by two areas of the motor system: the upper motor neuron (UMN) and the lower motor neuron (LMN).

UMN

UMN is located within the CNS (brain and spinal cord), and is responsible for initiating and maintaining normal movements and extensor muscles tone (to support the body against gravity). The UMN neurons are located in the brain (brainstem) and travel to the spinal cord in the white matter, where they indirectly synapse with the LMN neurons.

LMN

LMN connects the UMN to the muscles. In the spinal cord, the neurons’ cell bodies are within the ventral horn of the grey matter. The axons exit in the ventral horn of the spinal cord and they form a spinal nerve. The spinal nerve synapses with the muscles responsible for weight support, posture and gait.

The LMN is located within the spinal cord intumescences (C6-T2 for the thoracic limb; L4-S1 for the pelvic limbs). The integrity of these areas is tested in particular with the spinal reflexes. When examining an animal with a spinal disorder, the following gait abnormalities can be noted.

Lameness

Often related to an orthopaedic disorder, lameness can be present in case of nerve root signature (pain due to nerve root compression, often seen with foraminal stenosis due to lateralised intervertebral disc disease or nerve root tumour; Figure 3).

Ataxia

Ataxia is defined as incoordination. Three types exist: cerebellar, vestibular and sensory (or proprioceptive). Animals with lesions of the spinal cord white matter can show sensory ataxia.

Sensory ataxia is due to the interruption of the ascending proprioceptive pathways; therefore, the animal loses the sense of limb and body position in space. This gait is characterised by long strides and scuffing of the toes.

Paresis

Paresis is defined as weakness. Paralysis, or plegia, is defined as loss of voluntary movements and, therefore, inability to stand and show movements even when supported. UMN paresis is seen as inability to generate the gait, while LMN paresis is seen as loss of ability to support weight.

Paresis can be classified as:

- monoparesis: affecting one limb

- paraparesis: affecting the hindlimbs

- tetraparesis: affecting all four limbs

- hemiparesis: affecting forelimbs and hindlimbs on the same side

Ataxia and paresis are often present at the same time in cases of a lesion of the UMN.

Postural reactions

Postural reactions are the complex responses that allow an animal to keep its normal upright position. Postural reactions are used to determine whether the clinical signs are due to a disease affecting the nervous system: they help distinguish between orthopaedic and neurological conditions.

The entire nervous system, from the paw to the brain and spine, is required to perform postural reactions. They test the same pathways involved in gait (awareness of the legs in space and gait generation). They are used to evaluate asymmetry in the clinical signs, and to compare forelimbs and hindlimbs. The most commonly tested are proprioceptive positioning and hopping. In both tests, each leg is tested individually.

Proprioceptive positioning (paw replacement)

Proprioceptive positioning is performed by turning the animal’s paw, with its dorsal surface touching the ground. It is important to support the animal’s bodyweight while doing this test, to reduce the influence of weakness on the result. The animal should turn the paw to its normal position very quickly.

Hopping

While supporting the animal’s weight and the opposite leg, the patient should be moved laterally to allow the leg on the floor to hop to support the bodyweight.

In case of doubt, other useful tests are placing response, hemiwalking, wheelbarrowing and extensor postural thrust. These tests can be used in cats, as they often dislike their paws being touched so may not allow the clinician to perform the proprioceptive positioning.

Postural reactions should be performed several times, until the clinician is confident with the interpretation of the result.

References

- de Lahunta A and Glass E (2009). Lower motor neuron: spinal nerve, general somatic efferent system. In Veterinary Neuroanatomy and Clinical Neurology (3rd edn), Saunders Elsevier, St Louis: 77-133.

- Dewei CW and Da Costa RC (2015). Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology (3rd edn), Wiley‑Blackwell,New Jersey.

- Dewei CW and Da Costa RC (2015). Signalment and history: the first considerations. In Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology (3rd edn), Wiley‑Blackwell,New Jersey: 8.

- Dewei CW, Da Costa RC and Thomas WB (2015). Performing the neurologic examination. In Dewei CW and Da Costa RC (eds), Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology (3rd edn), Wiley-Blackwell, New Jersey: 9-28.

- Garosi LS (2012). Examining the neurological emergency. In Platt S and Garosi L (eds), Small Animal Neurological Emergencies, CRC Press, Boca Raton: 15-34.

- Platt SR and Olby NJ (2013). The neurological examination. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Neurology (4th edn), BSAVA, Gloucester: 1-24.

- Platt SR and Olby NJ (2013). Lesion localization and differential diagnosis. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Neurology (4th edn), BSAVA, Gloucester: 25-35.