4 Nov 2025

Nicola Lakeman MSc, BSc(Hons), CertSAN CertVNECC, VTS(Nutrition), RVN looks at aspects of an important part of dermatological work-up involving RVNs.

Image: Tatyana Gladskih / Adobe Stock

The terms food allergy and food hypersensitivity should be reserved for those adverse reactions to food that have an immunologic basis.

Food intolerance refers to cutaneous adverse food reactions, or CAFR, due to non-immunologic mechanisms. Distinction can be difficult, though, with diagnosis and treatment pathways being similar (Bethlehem et al, 2012; Mueller et al, 2012). Gaschen and Merchant (2011) suggested in a review of studies that only 1% to 6% of all dermatoses seen in practice relate to adverse food reactions and that food allergies constitute 10% to 20% of allergic responses in dogs and cats.

A full dermatological work-up is required before a nutritional factor can be entirely confirmed. It can be commonplace, however, for owners to self-diagnose their pet’s food allergy or intolerance, even before seeing the veterinary surgeon (Tiffany et al, 2019).

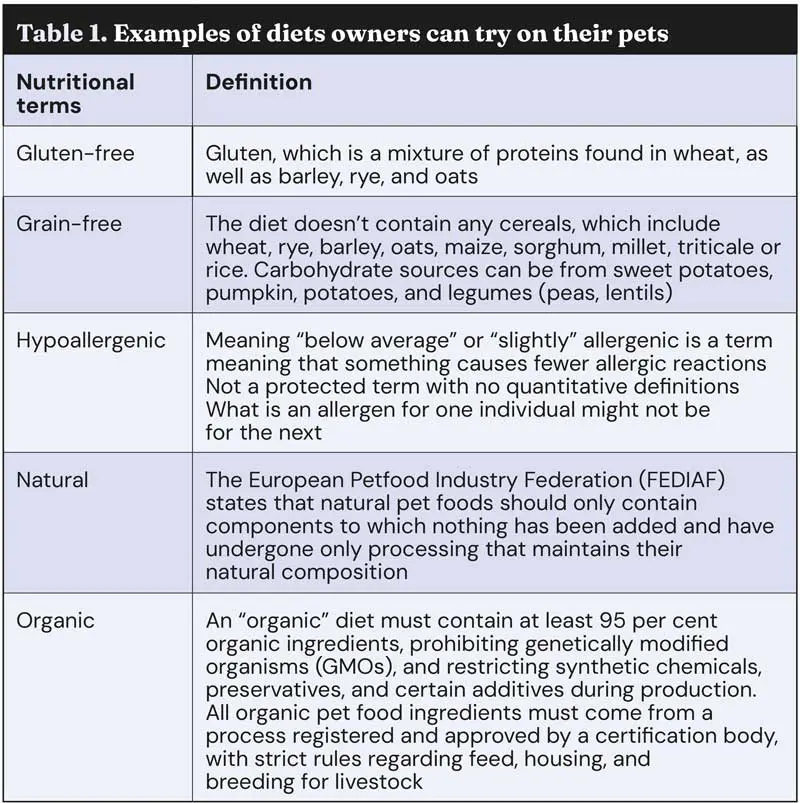

Many diets are available that are gluten-free, grain-free, hypoallergenic and/or natural (Table 1); and when the pet improves on these diets, the owners assume their pet had an allergy to one of the ingredients. In many cases, it can be purely a coincidence (Tiffany et al, 2019). These diets can appeal to many owners who are looking for a way to help their pet. Owners ultimately want to help their pets; they are looking for solutions to an issue.

The skin is the largest organ of the body and has a heavy demand on bodily nutrient supply. When factors become suboptimal, it is usually the skin that becomes the first organ to demonstrate deterioration.

When designing or recommending an elimination diet, certain characteristics do need to be taken into consideration. Reviewing the diet history will give you an indication of what the animal has been exposed to in the past. Excessive levels of protein should be avoided; the protein present needs to be of a digestibility greater than 87%, and, of course, novel to that pet if not using hydrolysed proteins.

Digestibility levels should be available from the food manufacturers. The use of hydrolysed protein can be useful, as digestibility is high, and identification of a novel protein source doesn’t need to be found. The diet needs to be nutritionally adequate for the animal’s life stage and body score.

The use of carbohydrates in the diet also needs to be limited, as in many elimination diets, the use of a novel carbohydrate source is also utilised. Carbohydrate sources used include rice, pumpkin, potato and tapioca. Some carbohydrate sources will also contain proteins, so using a novel source might be prudent.

The main diagnosis method for nutritional adverse food reactions is dietary elimination trials. To make a diagnosis of nutritional adverse food reactions, only the elimination food can be used.

The trial needs to be performed for several weeks to months, and full dedication from the owner is required. Olivry et al (2015) described complete remission of dermatologic signs of food allergies in 90% of dogs when the elimination trial was a minimum of eight weeks long, with some animals taking up to three months.

Tiffany et al (2019) found that with gastrointestinal signs, the duration of amelioration reported by owners was much more rapid, with recovery times varying from fewer than two weeks at minimum, and most clinical signs ameliorated by four weeks. This was attributed to the high cell turnover rate.

Newly generated intestinal epithelial cells migrate from the base of the crypts toward the villus tip region, where loss of senescent epithelial cells occurs. Complete renewal of the villus epithelium takes two to six days in most mammals (Moriello et al, 2010; Williams et al, 2015).

Elimination trials can prove to be extremely useful when diagnosing the causal nutritional agent in both dermatological and gastrointestinal disease. A strict elimination trial protocol does need to be adhered to, and the owner and anyone in contact with the animal needs to be aware of this. No other foodstuffs, other than the elimination food, should be ingested over this period. This includes treats, flavoured vitamins, chewable/palatable medications, fatty acid supplements and chew toys (for example, rawhide or dental chews).

Advice must be clearly conveyed to the owner when discussing the use of an elimination food trial. These trials are often difficult to interpret in dermatological disease. Confirmation of a diagnosis can be made of an adverse food reaction when the clinical signs recur after the animal is challenged with its original diet, which can be up to two to four weeks. Always give the client written instructions describing the requirements of the elimination trial and feeding quantities. Details on how to contact an advising veterinary nurse can prove useful if the owners have any questions during the trial or require support. Giving good, clear instructions, both verbal and written, can help in aiding with compliance.

In Europe, allergies to house dust and storage mites play an important role and are more significant than pollens. Positive reactions to Acarus are seen in between 45% to 95% of atopic dogs, to Tyrophagus in 60% to 89% and to Dermatophagoides farinae in 70% to 90%, depending on the literature source (Nuttall et al, 2008). Arlian et al (2003) showed that 94% of the dogs with atopic dermatitis had serum IgE against proteins originating from storage mite species. Brazis et al (2008) demonstrated that 90% of dermatological diets studied had storage mites evident after five weeks of opening the packaging.

Gill et al (2011) investigated how to store dry commercial foods. Mites were identified in six of 10 paper bags, three of 10 plastic bags, one of 10 plastic boxes and nine of 10 house dust samples after 90 days. This shows the importance of storage of the diet, cleaning the storage containers and only using volumes of food that would feed the pet for a month. Olivry and Mueller (2019) critically appraised the topic (CAT) of commercial diet contamination, finding 10 studies, of which five reported results of laboratory experiments and five from field studies.

Recommendations were made based on this CAT that commercial dry pet foods should be kept indoors and sealed to decrease the risk of contamination with storage mites. When performing dietary restriction (elimination) and provocation trials for the diagnosis of food allergies in dogs, it seems preferable to choose newly purchased bags of both original and testing diets to reduce the probability of their contamination with storage mites, especially T putrescentiae. There is a potential that storage mite contamination might lead to an erroneous diagnosis of food allergy in house dust mite-sensitised dogs (Olivry and Mueller, 2019).

Weeks or months of elimination of the reactive food may well lead to reintroduction of the food without reaction. This is known as tolerance, and its maintenance depends on establishing the threshold of both frequency and quantity for that person – in other words, eating the food occasionally may be tolerated, but reintroducing it in large quantities or on a very regular basis (for example, every day) might lead to symptoms recurring.

Monitoring of these cases will depend on the nature and possible cause of the initial problem. Many dermatological cases can present due to secondary traumas from pruritus.

Use of a diary to monitor possible causations can be useful; food records and pruritic scales can help gather data for the veterinary surgeon to make a diagnosis or in monitoring the efficacy of treatment plans. Taking pictures and measurements of affected areas can also prove useful.

Client guidance is needed in diet trials to ensure compliance. Veterinary nurses should take a pivotal role in aiding clients with these food trials, in both guidance and support throughout.

Monitoring of these cases can be effectively conducted within nurse-led clinics.