3 Jul 2021

Nursing patients with intervertebral disc disease

Elle Payne covers the grading and management of this common spinal cord condition, before detailing care that can be offered by veterinary nurses.

Image © Monika Wisniewska / Adobe Stock

Intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) is a common spinal cord disease that often presents in practice as an emergency.

Two types of IVVD exist: Hasen type I and Hasen type II. Hasen type I refers to extrusion of the nucleus pulposus through the annulus fibrosus of the disc into the spinal canal, causing compression to the spinal cord. This type is common in breeds such as the dachshund, shih-tzu, miniature poodle and cocker spaniel, which can occur around one to two years of age.

Hasen type II refers to the protrusion of the nucleus pulposus into the spinal canal, causing compression to the spinal cord. This type usually affects larger breeds such as the Labrador retriever, German shepherd dog and Dobermann.

This can be caused by the degeneration of the annulus fibrosis, which occurs when the water content of the disc diminishes and the collagen content increases, therefore resulting in a decrease of elasticity (Merrill, 2012).

IVDD grading

IVDD is graded on the severity of clinical signs based on the neurological examination to which surgical or conservative management is decided (Panel 1).

Grade 1

The patient will have pain as a clinical sign; however, no compression to the spinal cord exists at this stage (Merrill, 2012). Conservative management is certain.

Grade 2

The patient has ambulatory paresis (Freeman, 2014). The compression of the protruding disc will have an effect on the patient’s gait (weak and ataxic), but it can still walk. Conservative management remains appropriate.

Grade 3

The patient has non-ambulatory paresis (Freeman, 2014). The cord compression is now having an effect on the motor fibre tracts found deep in the cord parenchyma, meaning the patient can no longer walk; however, it has voluntary control of urination and with support may be able to have weak voluntary motor movements (Merrill, 2012).

Diagnostic imaging such as CT and MRI would be advised at this point, with surgery anticipated.

Grade 4

The patient is plegic (Freeman, 2014), and has no voluntary movement and no urination control, but may still be able to retain the ability to sense deep pain (Merrill, 2012). Surgery will be expected at this stage.

Grade 5

The patient is paralysed with no deep pain sensation below the level of the lesion (Merrill, 2012). The patient should have immediate decompressive surgery.

Conservative management

The main aspects of conservative management are activity restriction and pain relief medication. Cage rest is essential for patients that are grade 1 and grade 2, which can last as long as four to six weeks, with short lead walks in the day to promote physical and mental stimulation.

Pain relief medications, such as tramadol and gabapentin, are used to keep the animal comfortable and anti-inflammatory medications are used to reduce inflammation of the spinal cord.

Surgical management

Surgical decompressive surgery is the recommended treatment for patients with intervertebral disc herniation. It involves removal of vertebral bone to access the extruded or protruded disc material to remove it.

Recovery is faster than conservative management and gives a lower risk of recurrence (Freeman, 2014). Advanced imaging such as CT and MRI are always required preoperatively to ensure diagnosis and location of the lesion.

Nursing care

Bladder management

Patients that are paralysed often have an impaired ability to urinate on their own; therefore, the veterinary nurse must have good knowledge in bladder management. The main goal is to keep the bladder as empty as possible to prevent the risk of cystitis, urinary tract infections (UTIs) and urinary scalds.

Urinary scalds can be prevented by close monitoring of the patient and its bedding, and by applying a barrier cream or spray to the patient’s back end and hindlimbs. Patients with urine on them should be washed promptly and any wet bedding changed.

Manual expression can be achieved three times per day (Merrill, 2012), but care is needed when applying percutaneous pressure (Frogley, 2011) as a risk of rupturing the bladder exists.

Catheters can be used to drain the urine from the patient; however, this can lead to risk of trauma or introduce infection (Merrill, 2012).

Indwelling catheters are beneficial to use – especially in aggressive patients where draining of the urinary collection bag can be achieved without being close to the patient. This method is also good at maintaining hygiene as it will decrease the risk of urinary scalding; however, a risk of UTI exists, so close monitoring is essential by checking basic parameters, demeanour and urine presentation.

Drugs such as diazepam, phenoxybenzamine and prazosin can be used to help obtain relaxation of the urethra and sphincter muscles when patients have an upper motor neuron bladder disorder.

Postural support

Paralysed and non-ambulatory patients will benefit from postural support to prevent atelectasis. Walking patients still remains an important factor in recovery and helps to improve demeanour. Sling‑assisted walking is an easy and safe way to walk patients, but care must be taken to ensure each patient’s hindlimbs are not dragging on the floor as this can create sores.

Recumbent patients should be turned every four hours (Merrill, 2012), ensuring they are placed in sternal to prevent pressure sores, decubitus ulcers and hypostatic pneumonia (Frogley, 2011). Spinal patients should be placed on an orthopaedic mattress for comfort and to help support the patient.

Pain relief and fluid therapy

IV fluid therapy (IVFT) is used intraoperatively to maintain spinal cord perfusion and to support blood loss from surgery. IVFT care involves checking at a minimum of every two hours to observe for signs of overinfusion, such as restlessness, tachypnoea and SC or pulmonary oedema (Thompson, 2009). Postoperatively, the vet may request that the patient remains on IVFT until eating and drinking before removal.

Pain relief is imperative for these patients; therefore, patients typically have an opiate as analgesia during the first 24 to 48 hours postoperatively. Multimodal analgesia can be used, which would include medications such as an NSAID and gabapentin, but this will be at the vet’s discretion. Pain scoring should be achieved twice daily to ensure the patient is receiving the correct amount of analgesia.

Physiotherapy

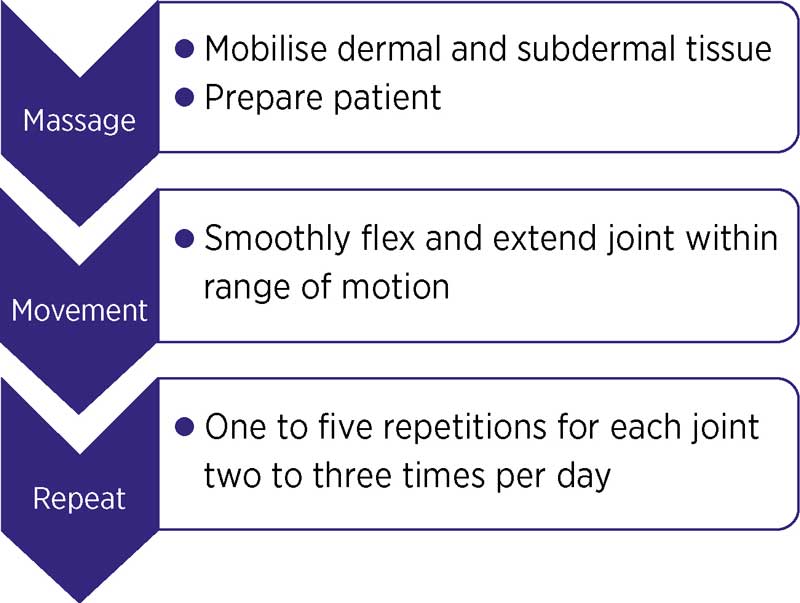

The use of physiotherapy is important to aid recovery in spinal patients, both surgical and conservative. The goal of physiotherapy is to help patients to return to normal function and gait re-education following injury (Thompson, 2009).

VNs can work alongside a chartered physiotherapist to create a plan that is tailored to the patient (Figure 1).

Patients should consume at least 85 per cent of their resting energy requirement daily (Merrill, 2012); therefore, efforts to get patients eating should be prioritised. It is important that the owner has let the veterinary team know of any allergies or food preferences the patient may have so that a feeding plan can be tailored correctly.

Different methods of feeding can be implemented, such as hand feeding (Figure 2), warming foods and trying a range of different foods. Fussy eaters may require their owner to come into the practice to visit and bring food for them to eat – this technique is normally successful as the patient has familiarity with its owner, and feels more comfortable and safer to eat with him or her.

TLC

Spending time with patients is something that can be forgotten due to having time restraints; however, cuddling, stroking and brushing patients can really help them feel better mentally and recover faster, and creates a bond between the veterinary nurse and patient (Figure 3).

Conclusion

Veterinary nurses play a pivotal role in nursing spinal patients using their key skills, a holistic approach and nursing care plans to improve patient recovery.

Spinal patients can be very challenging to nurse due to the frequent checks and assessments involved; however, nursing these patients can be the most rewarding.

- Some drugs are used under the cascade.

- Reviewed by Mark Lowrie MA, VetMB, MVM, DipECVN, MRCVS.

References

- Freeman C (2014). Intervertebral disc disease – overview and treatment options, Vet Times 44(22): 8-9.

- Frogley S (2011). Nursing the neurology patient, VN Times 11(12): 10-12.

- Merrill L (2012). Small Animal Internal Medicine for Veterinary Technicians and Nurses, Wiley-Blackwell, Ames.

- Thompson L (2009). Nursing the spinal patient, VN Times 9(11): 16-17.

Meet the authors

Elle Payne

Job Title