7 Dec 2022

OA and joint pain in pets: managing these cases in practice

Kirsty Cavill explains how the vet nurse can be an OA ambassador in practice, the importance of this role, and how to manage and treat cases seen in companion animals.

The RVN OA ambassador is a vital conduit between the practice environment and wider community, advocating for patients experiencing symptoms of OA and chronic pain.

VNs play a major role in developing and implementing multi-disciplinary care plans. They are instrumental in the signposting and integration of patient-centred, nurse-centric treatment plans, built upon strong evidence-based foundations, which are essential for the effective management of OA patients.

Value exists in employing a proactive approach to OA health parameters, starting with appropriate education when the pet is still young.

A safety net of relevant advice can be conveyed in a sympathetic manner to ameliorate any mitigating risk factors for the years ahead.

What is OA?

OA is a common degenerative and incurable disease of the synovial joints. It is multifactorial in nature, affecting the appendicular and axial skeletal systems, resulting in breakdown, and eventual loss of cartilage in one or more joints, leading to progressive, pathological changes, affecting the entire joint and associated soft tissues.

OA is not a single disease process, but the result of a combination of physiological, genetic, environmental and behavioural factors. It is associated with diverse phenotypes, multiple clinical presentations, varying rates of progression and often unpredictable responses to therapeutic interventions. It is not a one-size-fits-all disease.

The development of OA is associated with modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. A systematic review conducted by Anderson et al (2020), concluded that “OA continues to be highly prevalent within the dog population, with substantial implications for quality of life and welfare”.

How prevalent is canine and feline OA?

A total of 80% of dogs over the age of eight years (Anderson et al, 2020) and more than 20% of dogs over the age of one year are believed to be affected by osteoarthritic changes.

A total of 34% of cats of all ages have radiographic changes present (Clarke et al, 2005), 61% of cats of six years and older have radiographic changes present (Slingerland et al, 2011), and 90% of cats above 12 years have radiographic changes present (Hardie et al, 2002).

A correlation between increasing age and increasing frequency can be identified.

Lascelles et al (2010) carried out a prospective observational study designed to establish the prevalence of degenerative joint disease (DJD) in domesticated felines.

Cats were selected from four equal age groups (0 to 5; 5 to 10; 10 to 15; and 15 to 20 years old) were randomly selected (regardless of health status) for radiographic projections of all joints and the spine.

Results showed most (92%) cats had radiographic evidence of DJD, 91% had at least one site of appendicular DJD and 55% had more than or equal to one site of axial column DJD.

Affected joints in descending order of frequency were hip, stifle, tarsus, and elbow. The thoracic segment of the spine was more frequently affected than the lumbosacral segment.

For each one-year increase in cat age, the expected total DJD score increases by an estimated 13.6%.

In conclusion, the study said: “Radiographically visible DJD is very common in domesticated cats, even in young animals and is strongly associated with age” (Lascelles et al, 2010).

It’s not just dogs and cats

It is worth considering that smaller mammals, including rabbits, are also affected by OA.

Radiographic signs of the disease are evident in rabbits as early as one year of age, with older rabbits experiencing more than 70% occurrence (Arzi et al, 2012). The most affected joints were the stifle and the hip. In addition, a certain correlation of weight with the occurrence of OA existed.

OA – what a pain

So, why is OA such a problem? Because it hurts. The ability to experience pain is a trait common to all mammals. It is a sensory, perceptual, and multi-dimensional phenomenon, affecting emotion, quality of life and representing awareness of damage, or threat to the integrity of the body/tissues. It is neither static or predictable, and is a very individual experience.

The World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) recognises the need to address and eliminate the pain incidence – pain treatment gap. Its vision is to develop “an empowered, motivated, and globally unified veterinary profession that effectively recognises and minimises pain prevalence and impact” (WSAVA Global Pain Council).

Mathews et al (2014), in the WSAVA guidelines, described pain as “a complex multi-dimensional experience, involving sensory and affective components”.

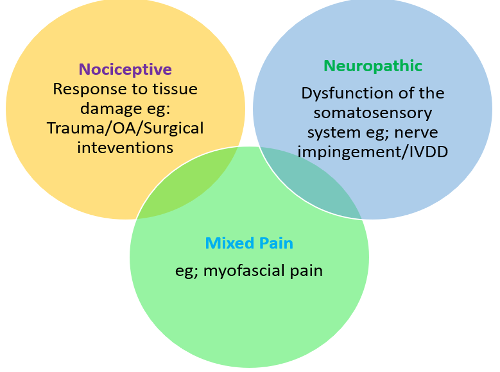

The pain states associated with OA are complex and transient (Figure 1), involving nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms.

Chronic pain

Chronic or maladaptive pain is representative of a malfunction in neurological transmission, and serves no physiological purpose or evolutionary advantage. It persists beyond the point of healing.

Chronic pain is not protective and does not facilitate healing. It is debilitating and can cause harm.

Chronic pain can become its own disease state:

- Breakthrough pain – an unpredictable and transient exacerbation of otherwise controlled background pain, which can affect patient outcomes. It is defined by the WSAVA as an “abrupt, short-lived, and intense pain that ‘breaks through’ the analgesia that controls pain” (WSAVA Global Pain Council).

- Myofascial pain – emanating from the muscles and fascia, and often associated with musculoskeletal areas of compromise, including myofascial trigger points.

Common presenting signs of chronic/breakthrough pain:

- Decreased exercise tolerance.

- Reduced interaction with people and other animals.

- Behavioural changes.

- Postural/gait changes.

- Changes in exercise tolerance.

- Licking/chewing limbs or joints.

- Altered sleep/wake patterns.

- Stiff following a period of exercise or rest.

- Reluctance to be stroked or groomed.

- Altered sleep/wake cycles.

- Toileting accidents.

- Over-grooming in felines.

- Hesitance in climbing stairs and high vantage points.

- Muscular atrophy from reduced mobilisation, weight loading or altered gait.

- Lameness.

OA is often referred to as “the silent disease” because animals will express signs of pain visually rather than verbally, so always ask yourself: “What is the patient telling me?”

Our patients will be communicating information about physical and emotional health all the time. They are giving us the clues that something is wrong. We must learn to read what they are saying. Assessment of pain in patients can be challenging as several underlying pathophysiological mechanisms may be present. However, identifying the presence of chronic pain can be most effectively achieved by asking the right questions, at the right time, to enable the formation of an accurate patient profile. Utilising effective pain scoring tools will enable a targeted approach:

- Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs (University of Liverpool).

- Feline Grimace Score.

Managing the OA patient

The VN is perfectly placed to play a proactive role in identification of patients, develop effective mechanisms of monitoring, remove barriers to clinic attendance and encourage owner understanding to aid in the management of patients with OA, through developing and employing evidence-based treatment plans, in conjunction with the wider veterinary team.

The management of OA and senior patients starts with a proactive, multi-disciplinary team approach. Start with a deep-dive discovery session with your colleagues and decide who will be the practice OA ambassador.

Developing an OA-aware practice environment

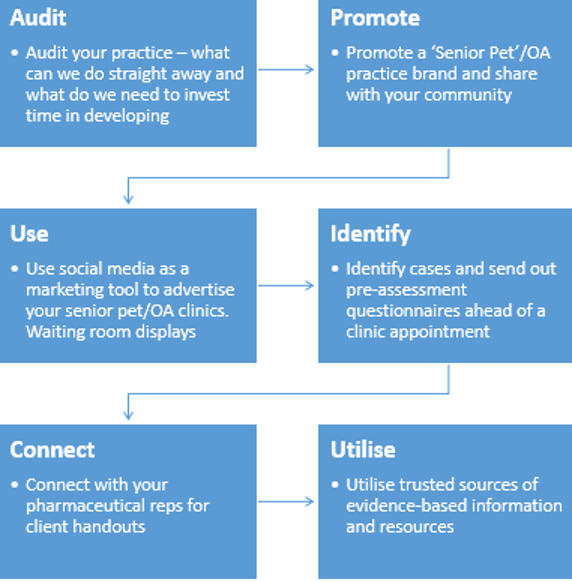

Audit your practice provision and share your vision (Figure 2).

Promote your practice “OA” brand and establish links with the practice community – your clients. Define your criteria for identification of patients and generate appropriate pre-assessment quality of life and pain score questionnaires.

Agree standard operating procedures for clinics, admission and hospitalisation of arthritic/senior patients, and define assets, equipment, terminology and methods for recording information.

Be proactive – not reactive

We must effectively educate owners about the importance of appropriate lifestyle, exercise, nutritional management and body condition scoring (BCS) from an early point in each pet’s journey through life before clinical signs become apparent or permanent damage has occurred.

Developing an effective strategy to convey the value of OA management to the practice business model will encourage a shift in culture towards a holistic and proactive approach.

Plan effectively, define your questions and allow sufficient time during a nurse-led consultation.

Is the practice environment suitable for OA patients?

Think floors. Can your patient safely navigate the waiting area to access the consulting room without slipping?

OA patients requiring in-patient treatment will need orthopaedic mats, raised food bowls, non-slip mats in kennels and the facility to mobilise regularly in a suitable environment.

Know what questions to ask and allow sufficient time for your clinic. The author would allow a minimum of 30 minutes per patient. Encourage a thorough diagnosis and be observant. Aim for the early identification of developing disease processes through careful questioning, observation and assessment.

Create a treatment plan based on defined objectives, including an immediate and longer-term care plan. Clearly identify your priorities and determine desired outcomes.

Nurse clinic check list:

- Named nurse teams are effective in developing a bond of trust with the owner to improve understanding, medication compliance, assessment of pain/gait/posture and effective transfer of information.

- Employing a proactive approach will aid to reduce risk factors known to result in episodes of breakthrough pain and progression of the disease process.

- Diet/nutrition/nutraceuticals/BCS – weight management assessments are components in an OA treatment plan.

- Lifestyle adaptations and exercise management plans.

- Standardised pain scoring metrics.

- Medication reviews – check for understanding and compliance, especially with a polypharmacy treatment plan in place.

- Concurrent disease processes – we must be alert to these impacting OA patients.

- Arrange check-ins between visits – aid in removing barriers to clinic attendance and help with compliance. Use video calls, text messages and emails.

- Define your client-specific outcome measures and pre-assessment questionnaires as part of a toolbox of assessment and treatment options.

Agree a whole team approach to assessment strategies for patient reviews and define strategies for identifying measurable change. Patients should be reviewed regularly to assess measurable change and pain status.

BCS and weight management

In 2018, the Association for Pet Obesity Prevention (APOP) found 56% and 60% of cats to be clinically obese (APOP, 2018).

Studies have shown that losing 6% of excess bodyweight alone will significantly reduce an arthritic dog’s lameness. Results indicated that bodyweight reduction causes a significant decrease in lameness from a weight loss of 6.10% onwards. Kinetic gait analysis supported the results from a bodyweight reduction of 8.85% onwards (Marshall et al, 2010).

Therefore, effective weight management strategies should be considered an essential tool in a multimodal approach to the management of OA.

Teaching an owner how to effectively BCS their pet at home is a valuable part of any treatment plan. This can easily be achieved in clinic and supported remotely. It’s worth noting that adipose tissue is not inert. It contains pre-inflammatory mediators, potentially adding fuel to the arthritic fire.

Lifestyle adaptations and exercise management – dogs

- Avoid unsupervised access to stairs – dogs with OA will often exhibit hindlimb muscular weakness increasing the risk of a fall and further injury.

- Slippery floors increase the risk of injury from repetitive microtraumas, slips and falls. The use of non-slip mats will help to mitigate this risk.

- Ramps – to access cars and reduce torsional forces through joints from jumping.

- Raised feeding stations – to reduce tension through the neck, spine and hindlimbs.

- Exercise consistency – avoid the weekend warrior. Shorter walks more frequently are more beneficial than longer walks. Allow the dog time to stop, sniff and “read the newspaper”.

- Avoid ball launchers or repetitive high impact activities.

- Provision of a comfortable sleeping area away from noise and drafts.

- Seasonal adaptations – coats, heat pads and cooling mats.

Lifestyle adaptations and exercise management – cats

- Avoid unsupervised access to stairs – cats with OA will often exhibit hindlimb muscular weakness.

- Slippery floors increase the risk of injury from repetitive micro-traumas. Use mats or runners for safe navigation around the home environment.

- Ramps/stairs – to allow cats to access high vantage points essential for their psychological wellness.

- Raised feeding stations – to reduce tension through the neck, spine, and hindlimbs.

- Encourage regular mobilisation through the initiation of games/interactive feeding.

- Low-sided, easy access litter trays.

- Regular cutting of claws to aid mobility.

- Comfortable sleeping area away from noise and drafts.

Non-pharmaceutical interventions

The use of distraction, engagement and exercise can all influence pain state. Consider interactive, feeding and activities to stimulate the senses.

Adding physical and targeted rehabilitation strategies into a treatment plan through the engagement of interprofessional collaboration plan can influence the patient’s overall well-being. Build a trusted network of therapists within your practice community to strengthen your scaffold of support around the patient and to facilitate a comprehensive multi-disciplinary treatment plan:

- Be proactive in referrals – it’s better to refer early than too late.

- Invite therapists into the practice for open days to meet the veterinary team and clients.

Summary

- The primary complication of OA is pain.

- Employ a proactive and multi-disciplinary management approach to achieve the most effective results.

- Remove barriers to clinic attendance and define your toolbox of treatment options.

- Create a treatment plan based on defined objectives, including immediate and longer-term care plans.

- OA ambassadors with named vet/nurse teams for effective assessment and continuity of care.

- Protect yourself and your team from burden transfer and emotional burnout.