6 Aug 2024

Sophie Platt and Sarah Cooper consider differences between cats and dogs in this condition.

Image © Africa Studio / Adobe Stock

OA is the most commonly diagnosed joint disease in veterinary medicine (Anderson et al, 2018). It is also one of the most underdiagnosed diseases of cats and dogs (Epstein et al, 2015), meaning its true prevalence is likely to be more extensive than realised.

With negative implications for both the affected animal and the owner, accurately diagnosing cases and managing them well is vital to optimise welfare.

The early signs of OA are often subtle and vague, so may not be recognised by owners or vets as indicators of OA pain (Wright et al, 2022). Early symptoms can be easily overlooked in younger animals, and signs put down to merely “old age” in more senior patients.

Although prevalence increases with age, historically it has been widely estimated that about 20% of dogs older than 1 year are reported to have OA (Johnston, 1997). However, a recent US-based study suggested that the problem of under-diagnosing OA may be much higher than previously thought. Using a questionnaire given to owners of dogs older than one year presenting at their vets, they identified 38% of the respondents’ dogs to be suffering from some degree of previously undiagnosed OA (Wright et al, 2022).

The alleviation of suffering with appropriate management is only possible if an accurate diagnosis is made in the first place, so a focus should be made on diagnosis, as well as treatment.

As animals cannot self-report pain, the responsibility for recognising pain lies with both owners and veterinary practitioners.

It is now accepted that the most accurate method for evaluating pain in animals is through behavioural observations. Owners should be educated in recognising behavioural changes, and practitioners must ensure they are not dismissed or mistaken for other problems (Epstein et al, 2015).

Visual observation of lameness is a common assessment tool for vets, but these assessments are poorly correlated with objective measures of limb function (Triviño et al, 2024), and hold potential for disagreement between clinicians. If a clinical examination of an osteoarthritic animal could be objectified and inclusive of the wide variety of pain presentations, the assessment would be more reliable.

Clinical examination of OA patients has the potential to be objectified using several tools.

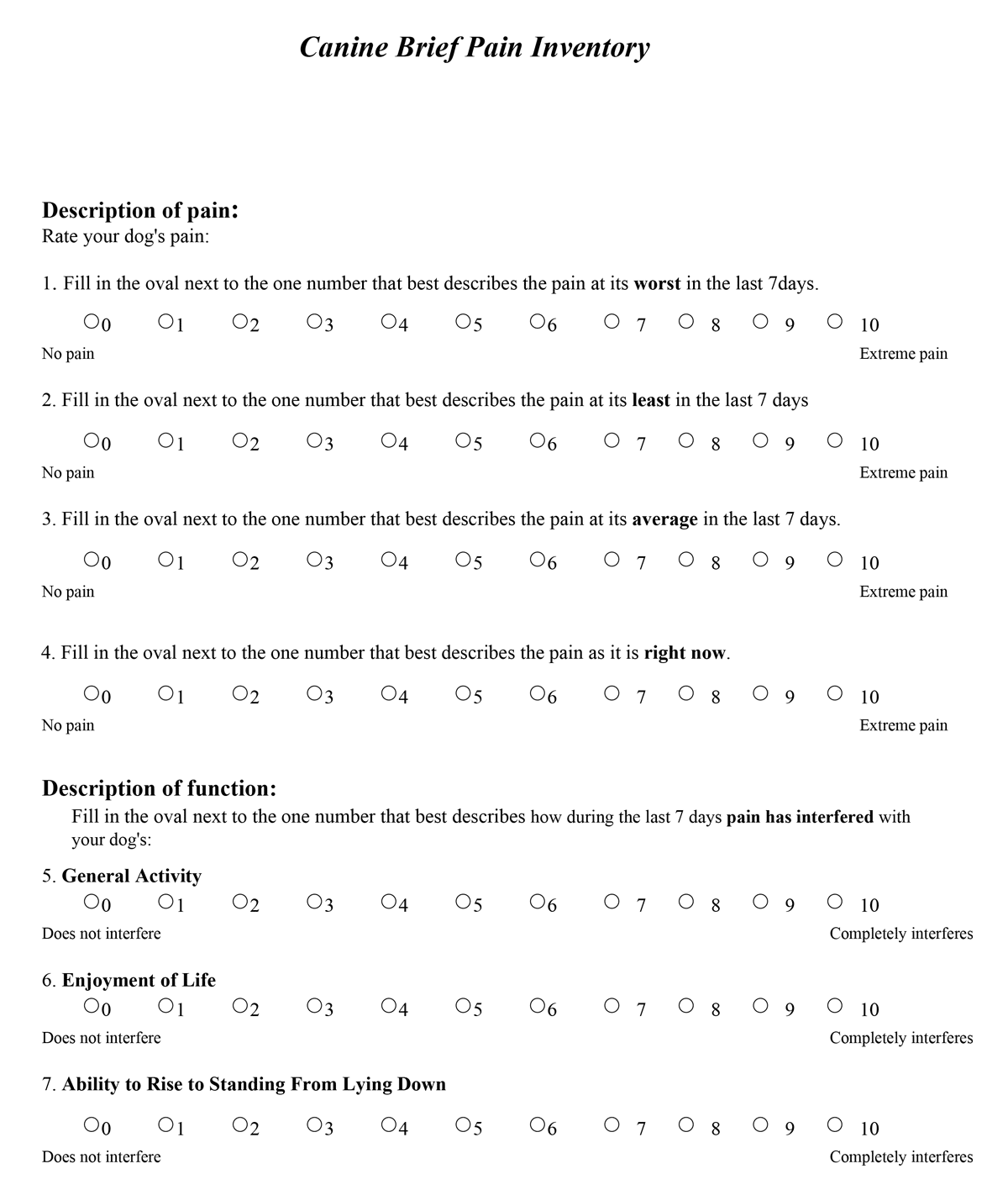

Questionnaires and scales can be utilised to aid diagnosis, as well as to assess response to treatment and disease progression (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs questionnaire (1a; accessed via tinyurl.com/2p9zpnt6) and the PennVet Canine Brief Pain inventory (1b; accessed via tinyurl.com/rd8nexj4).

Response to treatment is often assessed based on the owner’s perception of it, but caregiver placebo is a very real problem, so unguided owner assessment is an unreliable tool to depend on. Accepted canine examples include the Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs (LOAD) questionnaire (Walton et al, 2013) and the Canine Brief Pain Inventory (CBPI; Brown et al, 2008). When chosen appropriately and used consistently, they will reduce subjectivity and observer bias, leading to more effective pain management.

Thermography is a non-invasive screening tool that detects thermal skin temperature changes which can highlight changes in circulation within soft tissues and joints that may indicate pathology.

It can reliably distinguish between normal and OA joints in human patients (Borojevic et al, 2011). Interest is growing in its potential application in dogs for joint pathologies, intervertebral disc disease and bone neoplasia, but more research is needed in this area (Alves et al, 2021).

Signs of OA may be mild, but dogs that are not overtly lame may still show shifts in bodyweight distribution and off-loading when standing.

These changes can be measured with static force plates and pressure sensitive walkways, and used to objectify the clinical assessment (Alves et al, 2020) with a 76% sensitivity reported (Clough and Canapp, 2018). It also provides a visual tool to convince uncertain owners of the presence of off-loading.

They are not widely used in veterinary practices, but as technology advances, stance analysers may become a useful clinical modality.

Measuring joint angles with a goniometer in dogs has been shown to be as accurate as measuring the joints from radiographs (Jaegger et al, 2002), and provides an objective way to assess range of motion which will be reduced in OA.

This could help pinpoint specific joints affected at diagnosis or assess change over time. Similarly, a simple tape measure or tension tape could be used to measure muscle girth at set points to highlight muscle atrophy (associated with off-loading), acute swelling or disease progression (Hagler, 2015).

Although many similarities exist between arthritis in cats and dogs – a high prevalence on radiographs, and recognised under-diagnosis and under-treatment (O’Neill et al, 2014; Taylor and Robertson, 2004) – many differences of course also exist. Less is known about the aetiology of feline arthritis compared to dogs. Their behaviour within a veterinary setting also tends to differ from the home environment (Perry, 2020), and a full orthopaedic examination may be limited by their temperament (Perry and Meneghetti, 2023). These hindrances to veterinary-led observations make owner observations and the use of validated questionnaires such as the Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Checklist (Panel 1; Enomoto et al, 2020) vital for recognition and monitoring of arthritis.

It is important to acknowledge that a number of obstacles to treating cats exist.

Studies have shown that cats are less likely to be insured than dogs, and the pet-owner bond may be weaker with cats compared to dogs (Sandøe et al, 2023) which might reduce owner willingness to accept treatment or even access veterinary care in the first place.

A report by Cats Protection (2023) found around 10% of cats are not registered with a vet and only 61% of owners took their cats for annual check-ups. Barriers to veterinary care were reported as cost (28%), and the stress to the owner and cat (25%).

The recent growth in telemedicine and changes in RCVS guidelines will hopefully circumnavigate common obstacles, benefiting our feline patients and their owners.

OA is a complex disease characterised by chronic pain with acute flare-ups. It is important to recognise that chronic pain has physical, emotional and mental consequences for the affected animal (Panel 2), and it is vital to consider these wider ranging, as well as direct, effects when treating our OA patients.

It is also important to recognise and act to alleviate “caregiver burden”. Research has found that around half of people caring for a pet suffering from chronic illness may experience stress and symptoms of depression/anxiety, as well as a poorer quality of life, leading to a reduced ability to perform day to day activities and maintain relationships with friends and family (Spitznagel, 2017).

Factors that increase this burden include vets recommending changes to the pet’s routine as part of the treatment plan – especially where the owner perceives that changes would be difficult to make (Spitznagel, 2019). This caregiver burden can in turn impact the client-vet relationship, with increasing owner demands and expectations, or reduced desire to seek veterinary advice.

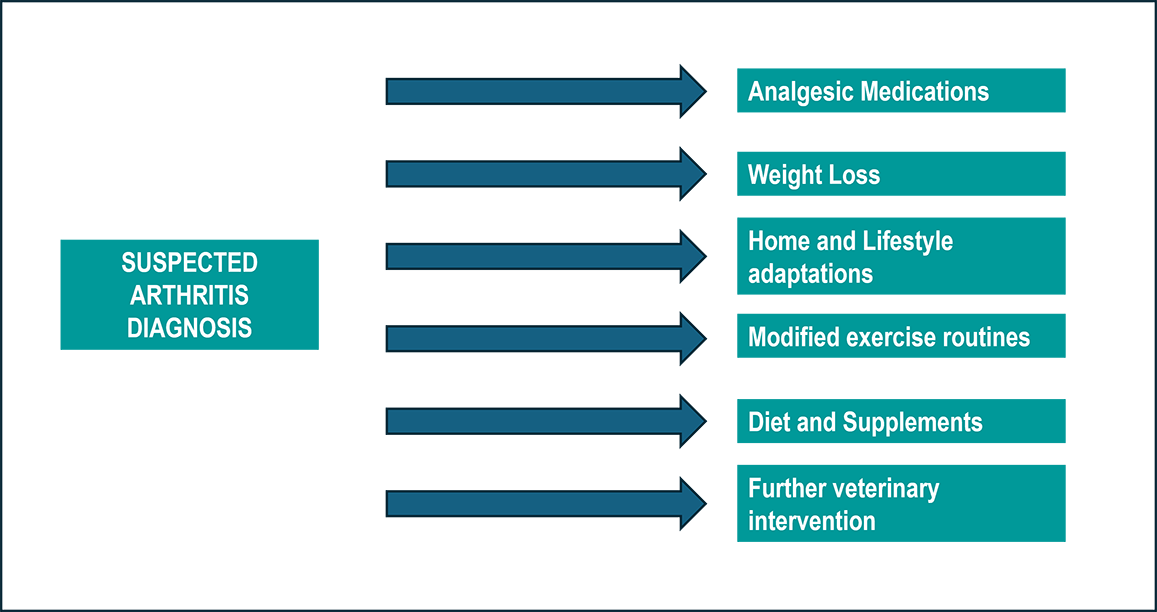

Treatment of OA needs to be multifactorial and contextualised (Figure 2).

As well as medication, physical therapies including physiotherapy and hydrotherapy can improve muscle strength and maintain joint function. It is also vital that owners consider their pet’s environment and routine, and make appropriate adjustments.

Analgesia must be at the forefront of any plan, but the medication options for cats and dogs differ in several ways. NSAIDs dominate the evidence base (Perry and Meneghetti, 2023), with many trials demonstrating benefit. They are the mainstay of treatment for both species, but only two drugs are currently licensed in the UK for feline OA: meloxicam and robenacoxib.

Comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) in feline patients can hinder their use and, therefore, cause welfare concerns for affected patients. One study showed that CKD had a prevalence of 68.8% in cats recruited for a trial looking at degenerative joint disease (Marino et al, 2014).

Although the presence of stable early CKD does not preclude the use of NSAIDs (Gowan et al, 2012), their use should be subject to a risk-benefit analysis.

Other analgesics including paracetamol, gabapentin, amantadine and ketamine can be used as adjuncts or alternatives to NSAIDs in canine patients, but paracetamol is not suitable for use in cats and even less literature exists to support the use of other medications in our feline patients.

Another popular adjunctive analgesia in dogs with OA has been tramadol. It is cheap and has a low incidence of side effects, but its efficacy is now in question due to its low bioavailability (Benitez et al, 2015; Budsberg et al, 2018). In cats, tramadol has more potential for effective pain relief (Monteiro et al, 2017), but its bitter taste can make it difficult to administer.

Forced pilling of cats should be avoided – especially for long-term conditions, due to the adverse effects it has on the pet-owner bond (Perry, 2020).

Monoclonal antibodies have broadened treatment options for OA in both cats and dogs. They significantly reduce OA-related pain (Lascelles et al, 2015) and have had a great amount of positive owner feedback. They appeal to owners due to the convenience of a monthly subcutaneous injection which negates the need for home medicating.

Both frunevetmab and bedinvetmab are species-specific, anti-nerve growth factor (NGF) antibodies. They have high binding specificity, so fewer suggested adverse effects than NSAIDs, and may not block protective nociceptive pain like opiates do (Kronenberger, 2023).

They appear safe and relatively few side effects have been published (Gruen et al, 2021), but their use in practice in the UK is still in its infancy, so we must remember their novel status and that the long-term safety and efficacy has not yet been fully established (Kronenberger, 2023). Frunevetmab and bedinvetmab are currently licensed for the treatment of OA only.

NGF is crucial for the growth, maintenance and survival of nerve cells, so the effect of anti-NGF antibodies in neurological conditions (for example, intervertebral disc disease or degenerative myelopathy) is yet unknown and may actually worsen the disease (Millis, 2023).

The wide-ranging negative impacts OA has on an animal should not be underestimated.

As well as the impact of pain itself, the emotional and psychological consequences of living in persistent pain, as well as a reduced ability to exercise and function normally, will affect its enjoyment of life, and it can affect the pet-owner bond through altered behaviours and preferences.

Accurately identifying OA in our patients is vital so appropriate management can be initiated and suffering reduced.

The caregiver burden should be an important consideration for vets, as owners will experience financial, emotional and physical burdens when caring for a pet with OA. Effective communication between the vet and owner is crucial to optimise compliance, and ultimately improve the quality of life for their pet.