4 Feb 2019

Karen Perry, in the first of a three-part article series, looks at latest thinking on functional changes related to this disorder in dogs.

OA is the most commonly encountered musculoskeletal disorder, and results in a complex pain state involving both nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms. The disease is incurable, with negative consequences related to pain, mobility impairment and decreased quality of life. Treatment aims to palliate the painful symptoms associated with the condition. However, pain is a subjective experience, unique to each individual, and despite tailored, multimodal management strategies, management of pain in patients with OA remains disappointing. This has led to a quest to better understand the mechanism of OA-related pain.

Inflammation, mechanopathology and central augmentation of pain perception have all been proposed to play a role in the development and persistence of OA-related pain. The contributions of each of these to the development of chronic pain in OA are discussed in this article and used to highlight the challenges associated with pain management.

OA is the most commonly encountered musculoskeletal disorder – a slowly progressive, degenerative joint disease characterised by global joint structural change, including the articular cartilage, synovium, subchondral bone and periarticular components, which can lead to pain and loss of joint function1-4.

The major clinical outcome of OA is a complex pain state that includes nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms5. The disease is incurable, with negative consequences related to pain, mobility impairment and decreased quality of life6. Pain results in local and distant deterioration of the musculoskeletal system as a result of decreased and altered mobility.

Additionally, the ongoing nociceptive input into the CNS results in somatosensory system changes and central sensitisation7,8, which contributes to the perception of pain.

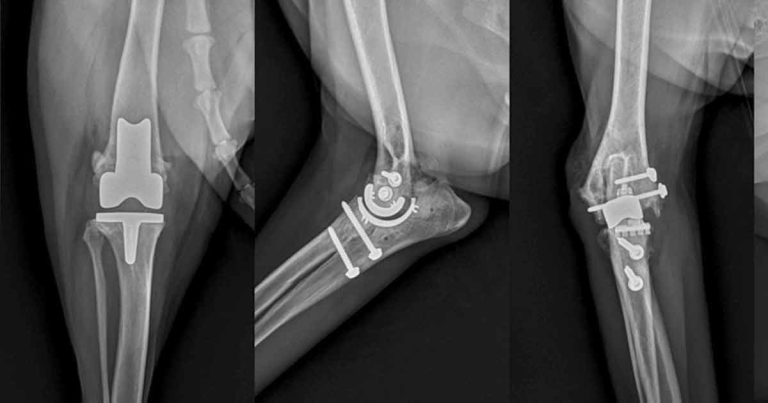

The combined effects of pain, central sensitisation and activity impairment may have negative effects on the affective state, heightening anxiety, depression, sleep impairment9 and cognitive dysfunction, as reported in humans10,11. In the later stages, the pain associated with OA can become severe to the point the patient is a candidate for joint replacement (Figure 1).

OA affects a large proportion of the companion animal population, with an estimated 20% to 30% of dogs, and up to 40% of cats, being affected clinically3,12,13. Although most commonly initiated early in life by developmental disease, many other factors play a role in the development of OA, including diet, genetics, environment, obesity and age4,14,15.

Our companion animal population is an ageing one and this – in addition to the increasing prevalence of predisposing factors, such as obesity – means the number of pets affected is only likely to increase.

In patients with OA, the most prominent symptom is chronic pain. Management of pain in this cohort of patients is still disappointing – hence the quest for understanding the mechanism of OA-related pain.

OA has been described as a primary disorder of cartilage. However, as the disease progresses, all tissues and structures of the joint can be affected, resulting in impaired joint mobility and increasing levels of pain.

From a histological standpoint, OA is characterised by degradation of cartilage, bone lesions and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate16. Inflammation triggers a cascade of events driven by inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, chemokines, prostanoids, proteolytic enzymes, and nerve and vascular growth factors, leading to enhanced cartilage turnover and matrix degradation16.

Inflammatory processes activate peripheral nociceptors that innervate the synovial capsule, periarticular ligaments, periosteum and subchondral bone, contributing to peripheral sensitisation and hyperexcitability of nociceptive neurons in the CNS17. Chronic synovitis is associated with marked changes in the central connexions of sensory nerves and changes in their synthesis, and release of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators.

Stimulation of primary sensory neurons is further promoted by neovascularisation of the articular cartilage, mediated by hypoxia, and production of angiogenic growth factors by activated immune and endothelial cells in the inflamed synovium. The formation and innervation of these vessels are important pathophysiological pathways causing the deep joint pain sometimes described by human patients with OA18.

Angiogenesis perpetuates chondrocyte hypertrophy, endochondral ossification, and osteophyte formation in the richly vascularised and innervated osteochondral junction, contributing to the exaggeration of pain. Finally, pain in the affected joints is also precipitated by periosteum irritation caused by abnormal bone formation, subchondral microfractures and cysts, bone marrow lesions and localised bone ischaemia19.

While both mechanopathology and inflammation participate in OA pain experience, their precise contribution may vary from time to time and from individual to individual. In addition, they are not sufficient to explain the disparity between the degree of pain perception and the joint damage in a significant proportion of patients, indicating OA pain is multidimensional in its nature and mediated by multiple factors.

No objective measurement exists – such as radiographs, ultrasound or MRI – in which the extent of bone/cartilage damage or the intensity of synovial inflammation can predict the presence or severity of pain20. Many patients with radiographic evidence of damage have no pain and patients with minimal, or even non-radiographically detectable, cartilage abnormality exhibit significant, debilitating pain.

In this respect, the role of central pain processing pathways has attracted the interest of rheumatologists and pain specialists, and recent advances in this field have provided a different point of view in the aetiology and management of pain in this population16.

Central augmentation of pain perception in patients with OA has been proposed17. Several studies have reported the presence of hyperplasia21, low thresholds for mechanical and thermal stimuli22,23, and referred pain24 in patients with OA, indicating a non-nociceptive pain component associated with abnormally excitable pain pathways in the peripheral and central nervous systems. Numerous publications support the notion neuropathic pain mechanisms contribute to the pain experience for at least a subset of the OA population25-29.

Neuropathic pain has been defined as “pain arising as a direct consequence of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory nervous system”30. In contrast to inflammatory or nociceptive pain, which is caused by actual tissue damage or potentially tissue-damaging stimuli, neuropathic pain is produced by damage to the peripheral or central nervous systems; peripheral disturbances cause abnormal impulse generation and transmission, while central disturbances cause abnormal processing of the information and excitability16.

This brief pathophysiology review highlights some substantial challenges encountered when attempting to manage OA-related pain; a variable degree of pathologic change is encountered – including bone and soft tissue, mechanopathology and inflammation – and the contribution from each varies between different individuals, times and even joints in the same individual.