18 Feb 2019

Karen Perry uses a case involving a German shepherd dog to demonstrate successful treatment of this condition.

OA is the most commonly encountered musculoskeletal disorder and results in a complex pain state involving both nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms. The disease is incurable, with negative consequences related to pain, mobility impairment and decreased quality of life.

Treatment aims to palliate the painful symptoms associated with the condition, with NSAIDs forming the cornerstone of medical therapy. However, pain is a subjective experience, unique to each individual, and tailored, multimodal management strategies adjusted to the clinical characteristics of each individual are required.

Despite conscientious employment of such strategies, including weight management, exercise modification, dietary support, physical rehabilitation, anti-inflammatory drugs, additional analgesics and intra-articular treatments, many dogs continue to experience chronic pain. In such cases, surgical intervention may be required, with total joint replacement representing the mainstay of salvage surgical management.

In the first part of this three-part series, the pathophysiology of OA-related pain was discussed. Extensive variability is encountered in terms of the structures affected, the relative contributions of mechanopathology and inflammation, and the potential contribution of neuropathic pain.

In addition, these contributions can vary between different joints and different times within the same individual. This substantially complicates management of OA-related pain and necessitates the use of multimodal management strategies, which should be tailored to the individual patient.

In this article, we will explore the management of a challenging case with OA, including management decisions made and potential alternatives that could have been considered.

Wolfy was a four-year-old German shepherd dog that presented for assessment of pelvic limb weakness. While he had previously been able to go for three-mile walks, he had later only been able to walk for about half a mile. The owners noted he avoided standing for long periods, preferring to sit or lay down, and could no longer jump into the car.

Wolfy was bright, alert and responsive on presentation, and his general physical examination was within normal limits. His body condition score (BCS) was ideal at 5/9 (WSAVA Global Nutrition Committee scoring system). Gait assessment revealed a stiff and stilted pelvic limb gait bilaterally. Mild muscle atrophy of both pelvic limbs was noted, slightly worse on the left. A decreased range of motion was observed of both hips, particularly in extension, and a moderate pain response was noted on extension and abduction bilaterally.

Pelvic radiographs were taken (ventrodorsal and lateral views), which revealed poor coverage of the femoral heads by their respective acetabulae. Osteophytes were noted circumferentially around both acetabulae and the acetabulae were remodelled. Bilaterally, large osteophytes were noted around the femoral necks at the level of the joint capsule insertion. The radiographic diagnosis, supported by the clinical findings, was bilateral hip dysplasia with moderate associated OA.

The decision was made to manage Wolfy with exercise modification, physical rehabilitation, anti-inflammatory medication and dietary modification. While little is known about the effects of exercise in people or animals with OA, it is generally recommended moderate exercise is beneficial – with no exercise potentially being as detrimental as extremes of exercise (Pettitt and German, 2015). Consistent levels of low-impact activity were advised with avoidance of any high-impact activity. This started with lead walks several times a day of short duration; the duration of the walks increased gradually to Wolfy’s tolerance.

A distinct paucity of evidence supports the effectiveness of physical rehabilitation techniques in small animals; however, rehabilitation has been used in patients with OA to reduce pain, control inflammation, improve strength and balance, increase range of motion, prevent muscle spasm and restore more normal joint function (Clark and McLaughlin, 2001; Bockstahler et al, 2004; Crook et al, 2007; Millis, 2001; Millis and Levine, 1997; Saunders et al, 2005; Taylor et al, 2004). These benefits may result from increasing blood and lymph flow through the affected area, resolving inflammation, preventing or minimising muscle atrophy and preventing periarticular contracture (Tanger, 1984).

In some cases, physical rehabilitation has been reported to reduce the dose of analgesics required to maintain patient comfort (Taylor et al, 2004). Rehabilitation programmes must be tailored to the individual patient to be effective and generally consist of a combination of modalities. For Wolfy, this included cryotherapy initially, followed by the application of moist heat, stretching exercises, massage therapy, therapeutic laser and active exercise. Other potential modalities that may be considered include balance and proprioception exercises, therapeutic ultrasound and electrical stimulation.

NSAIDs are the most widely used analgesics in veterinary medicine (Lascelles et al, 2005) and form the cornerstone of OA treatment (Aragon et al, 2007) being used to relieve pain and promote functional improvement (Sanderson et al, 2009). Globally, several NSAIDs are approved for use in dogs and, in this case, deracoxib was chosen. The efficacy of NSAIDs for the treatment of OA is unquestioned.

Although some veterinary studies suggest a difference between NSAIDs with respect to analgesic quality (Hazewinkel et al, 2008), it is generally accepted little difference exists among the approved NSAIDs with respect to the level of symptom relief – Wolfy had received deracoxib in the past without experiencing any adverse events, prompting this choice.

A gradual change to a diet formulated to support osteoarthritic joints was also recommended. Dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids has been highlighted as the only nutraceutical with a sound evidence base supporting its use in companion animals (Vandeweerd et al, 2012).

Arachidonic acid (AA) is normally the predominant fatty acid in cell membranes; however, supplementation with increased levels of omega-3 fatty acids results in their incorporation into cell membrane phospholipids and increased eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) content (Goodnight et al, 1982).

When eicosanoid metabolism is induced, the EPA competes with available AA as a substrate for the cyclooxygenase enzymes, altering the levels and types of inflammatory mediators produced (Goodnight et al, 1982; Seiss et al, 1980; Smith, 2005). The metabolism of EPA produces relatively less inflammatory prostaglandins, which can have an impact on the catabolic pathways and therefore on disease progression in OA (Henrotin et al, 2011).

Supplementation has been shown to have an ameliorative effect on OA in pet dogs (Roush et al, 2010a), resulting in improved weight bearing (Roush et al, 2010b) and allowing for a more rapid reduction in carprofen dosage, compared with feeding a controlled diet (Fritsch et al, 2010).

As Wolfy was an ideal BCS, weight reduction was not a required part of his treatment regimen. However, the owners were advised to monitor his weight carefully to prevent any gain associated with his reduced exercise levels. In patients that are overweight, weight control is an integral aspect of managing OA and weight loss alone may substantially improve clinical signs in overweight dogs. Weight loss has been reported to significantly decrease the severity of hindlimb lameness (Impellizeri et al, 2000), reduce the prevalence and severity of OA (Kealy et al, 2000) and improve patient mobility (Mlacnik et al, 2006).

Wolfy progressed very well with this treatment plan for approximately 11 months. At this time, the owners noted his exercise tolerance reduced again. He became particularly painful in the evenings, with vocalisation sometimes reported, and was stiff on rising after rest. As his treatment regime was no longer effective, alternative options were considered.

Wolfy is certainly not a unique case in this regard; despite their widespread use, and obvious benefit in many cases, NSAIDs are not always sufficiently effective when used as monotherapy (Lascelles et al, 2008).

However, beyond NSAIDs and the approved drug of the piprant class, grapiprant (Rausch-Derra et al, 2016), evidence-based treatment options for the control of pain are limited (Enomoto et al, 2018). OA-related pain can be a challenging clinical entity to treat and, indeed, is one of the most common reasons for euthanasia in dogs (Moore et al, 2001; Lawler et al, 2005). Therefore, an urgent need exists to develop more consistently effective treatments for OA-related pain in dogs and cats (Enomoto et al, 2018).

While centrally acting drugs have different modes of action and are approved for other indications, the evidence for central pain perception in OA provides the rationale for the administration of such therapies in patients with severe chronic joint pain of a degenerative nature. Whether such treatment options can complement the peripheral acting regimens and become part of a multi-pronged approach that targets various mechanisms of pain perception in OA remains to be determined (Dimitroulas et al, 2014).

The decision was made to institute multimodal analgesia for Wolfy, adding amantadine and gabapentin to his treatment regime. The basis of multimodal analgesia is to use a combination of drugs that act at different levels of the pain pathway and have a synergistic effect – hopefully improving pain control and, possibly, allowing lower doses of individual drugs to be used, reducing the risk of side effects.

Gabapentin is a structural analogue of gamma-aminobutyric acid that appears to decrease central sensitisation by inhibiting presynaptic calcium channels in the dorsal horn. Amantadine is an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist that may decrease central sensitisation, and has also been suggested to enhance the effects of NSAIDs and gabapentin (Moore, 2016; Lascelles et al, 2008).

Alternative options that could have been considered include pregabalin, codeine, amitriptyline or tramadol, although recent evidence has questioned the effectiveness of tramadol in dogs with OA, rendering this a less appropriate choice (Budsberg et al, 2018). Unfortunately, limited evidence supports the use of any of these options.

No controlled studies have been published evaluating the efficacy of gabapentin, pregabalin, codeine or amitriptyline in dogs with OA, and only one study evaluating the use of amantadine where it was evaluated in conjunction with NSAID use and proven to provide a greater treatment effect in dogs with OA than the same NSAID alone (Lascelles et al, 2008).

Although it was not performed at this time, another option would have been changing the NSAID. Other NSAIDs available for treatment of OA in dogs include carprofen, meloxicam, firocoxib, robenacoxib, phenylbutazone, mavacoxib, cimicoxib, ketoprofen and tolfenamic acid. In people, evidence exists that one NSAID may be more beneficial than another for a specific individual (Wegman et al, 2003).

It is reasonable to presume dogs and cats have a similar response to NSAIDs and, therefore, in a patient where one NSAID does not provide symptomatic relief, another NSAID could be trialled.

Wolfy returned for evaluation six weeks after adding amantadine and gabapentin into his treatment regimen. While the owners noted a reduction in his vocalisation, the remainder of his clinical signs remained unchanged. He would not stand or sit for more than a minute at a time and the owners felt his quality of life was severely adversely affected. Gait assessment revealed a bilateral hindlimb lameness, slightly more severe on the left.

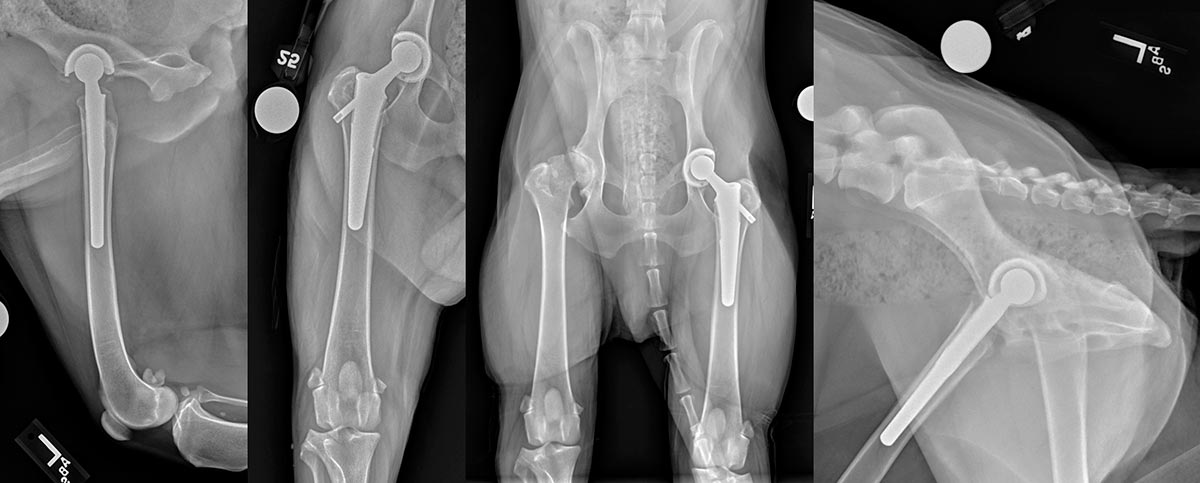

Moderate muscle atrophy was evident affecting both hindlimbs. The range of motion of both hips was moderately reduced in extension and abduction with marked crepitus and a pronounced pain response evident on the left. Radiographs were repeated, which revealed progression of the previously detailed degenerative changes (Figure 1).

Unfortunately, due to the complex nature of managing the pain associated with OA, pain frequently remains an intractable problem in both companion animals and humans. With the impact this was having on Wolfy’s quality of life, alternative options had to be considered.

Autologous platelet therapy may have been an option. Intra-articular injection of autologous platelets holds promise as a treatment for canine OA, with the growth factors present in platelets reportedly enhancing regenerative processes in osteoarthritic joints. Although the specific mechanism of action of the platelet-rich products remains speculative, they have been shown to promote the repair and remodeling of injured tissues, and prevent cartilage degradation and atrophy of the periarticular structures (Anitua et al, 2013).

Benefits in animals following autologous platelet therapy have been shown in multiple studies, including macroscopic and histological improvements in rabbits with OA (Kwon et al, 2012), improvements in lameness, activity and pain in dogs with OA (Franklin and Cook, 2013; Fahie et al, 2013), and reduced progression of osteoarthritic changes following cranial cruciate ligament surgery (Silva et al, 2013).

Along a similar vein, treatment with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) could have been considered. The mechanisms of action of MSCs are multiple and exactly how they result in symptomatic improvement in cases of OA remains contentious. Proposed theories include immunomodulatory effects (Gimble et al, 2007; Nasef et al, 2007; LeBlanc, 2006; Fang et al, 2007), cell-based tissue regeneration (Nathan et al, 2003) and trophic mechanisms (Chopp et al, 2000).

Studies in dogs with hip OA have demonstrated intra-articular MSC therapy can result in improved lameness, range of motion and pain on manipulation (Black et al, 2007; Vilar et al, 2014).

While less commonly used, and reserved for cases that have become refractory to other treatments, intra-articular injections of corticosteroids could also have been considered. Systemic steroid therapy should be avoided due to the potential adverse effects associated; however, a long-acting intra-articular injection of methylprednisolone acetate may provide prompt alleviation of clinical signs without inducing systemic side effects. The response to these injections is generally rapid and significant, but, unfortunately, relatively short-lived – often requiring repetition.

Intra-articular treatments were avoided for Wolfy, as the owner elected to proceed with surgical intervention. Surgical management is an appropriate consideration in the subset of patients with OA where satisfactory amelioration of symptoms cannot be achieved with non-surgical therapies. The mainstay of surgical OA management is total joint replacement, with commercial joint replacements being available for the hip, stifle and elbow in the dog.

Total ankle replacement is also available for dogs, but only performed by a specific subset of surgeons at this time; once results have been satisfactorily documented from this limited roll-out, the system will become more widely available.

Total hip replacement (THR) is the most commonly performed joint replacement procedure and associated with great success; excellent function is reported in more than 90 per cent of cases (Allen, 2012). This procedure was elected for Wolfy. As the left side was clinically more severely affected, this was the side operated. A BFX lateral bolt system was used (Figure 2). Surgery was uneventful and Wolfy recovered smoothly (Figure 3). He was discharged with instructions for strict exercise restriction for the following 12 weeks to limit the risk of postoperative complications.

Wolfy was monitored closely following surgery with examinations, including radiographs, at 6, 12 (Figure 4) and 24 weeks postoperatively. He recovered very well, recovering muscle mass and a normal range of motion of the left hip with no associated pain. Importantly, however, despite successful replacement of the left hip, OA in the right hip did require ongoing medical management.

At this time, more than 18 months postoperatively, his clinical signs associated with the right hip are well controlled with intermittent deracoxib therapy indicating the left THR has substantially facilitated non-surgical management of his condition.

Yearly revisits are recommended for any patient following THR to monitor for any evidence of implant loosening, infection, subsidence or wear. In many situations, if such complications are noted early, often before they are causing any clinical signs, substantially easier ways are available to resolve the issue than if the patient only presents after catastrophic failure.

While Wolfy progressed well following THR, these invasive procedures represent a substantial cost to the owner, not just in terms of finances, but also time. Many owners cannot commit to the financial requirements and struggle to designate the required time for both the intensive recovery period and lifelong monitoring required. The potential complications may also act as a sufficient impediment to surgery; complications following THR, for example, generally require further surgery and, therefore, further additional expense to resolve. Additionally, total joint replacement is not available for every joint.

In cases where total joint replacement is not feasible, arthrodesis may represent a suitable alternative. While arthrodesis does relieve OA-associated pain, it also obliterates motion at the affected joint and is best suited for low-motion joints, such as the carpus and tarsus. While the cost commitments associated with arthrodesis may not be substantially different from joint replacement in the short-term, no requirement exists for lifelong monitoring in these cases and may represent a superior option for some owners.

For the hip joint, as in Wolfy’s case, arthrodesis is not possible and, therefore, the alternative surgical option would have been a femoral head and neck excision (FHNE). While FHNE cannot be anticipated to result in normal function of the hip joint, functional results are achieved in the majority of patients and complications are uncommon. Owners should be warned, however, that in dogs with bilateral hip OA, bilateral surgeries may be more likely to be necessary with an FHNE than following THR.

When making decisions regarding the care of dogs with OA, it is critical to involve owners in the decision-making process. Owners of osteoarthritic dogs have been interviewed regarding what it is like to live with, and make decisions about, a dog with OA (Belshaw et al, 2018). The effect on owners can be profound, including constraints on their time and increased stress, which must be taken into consideration. Owners may require substantial support during this decision-making process.

As can be seen from this case, management of OA-related pain can prove very challenging, sometimes necessitating aggressive surgical techniques to provide satisfactory quality of life. A large, unmet need exists for additional therapeutic approaches for OA, both to facilitate pain management and control disease progression. This represents a vast area of research, both in the human and the veterinary fields.