20 Jan 2026

Ophthalmology: corneal ulcers in feline patients

Zuzana Klimova MVDr, MRCVS and Renata Stavinohova MVDr, PhD, PGCertSAOphthal, DipECVO, MRCVS consider the aetiologies, diagnostic approach and treatment options for this disorder in cats.

Image: Marcos Fine Images / Adobe Stock

Corneal ulceration is a frequently encountered and clinically significant ophthalmic disorder in feline patients. It is characterised by disruption of the corneal epithelium with variable involvement of the underlying stroma.

The condition is associated with substantial ocular discomfort due to the dense sensory innervation of the cornea and, if inadequately managed, can result in progressive corneal damage, visual impairment or irreversible blindness. Early recognition and appropriate therapeutic intervention are, therefore, critical to achieve a favourable outcome.

This article aims to review the principal aetiologies, diagnostic considerations and therapeutic strategies relevant to corneal ulceration in cats.

Anatomy, physiology and function of the feline cornea

The feline cornea is a highly specialised, transparent structure that plays a vital role in both vision and ocular protection.

Composed of four distinct layers – the epithelium, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium – it functions as the primary refractive surface of the eye while also serving as a physical and immunological barrier against pathogens and trauma. Its avascularity and dense collagen arrangement ensure optical clarity, while the rich innervation from the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve contributes to corneal sensitivity and a rapid healing response.

The corneal surface is protected and nourished by the tear film, which provides lubrication, oxygenation and metabolic support; compromise of this structure predisposes to epithelial breakdown and ulcer formation (Maggs, 2018).

Aetiologies

- Feline herpesvirus-1 (FHV-1) infection.

- Infected corneal ulcer and keratomalacia.

- Bullous keratopathy.

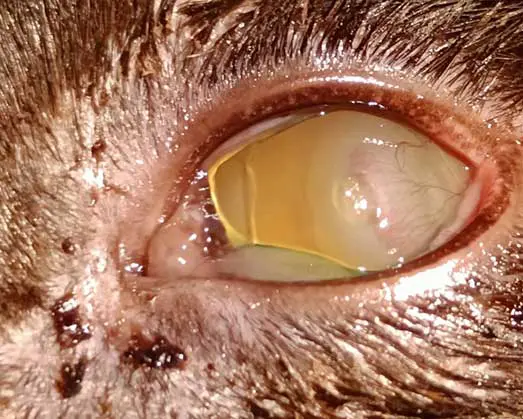

- Feline corneal sequestrum.

- Eosinophilic keratitis.

- Mechanical trauma and foreign bodies.

- Eyelid or eyelash abnormalities (entropion, ectropion, distichiasis, trichiasis).

- Exposure keratitis; from incomplete blinking or reduced tear film coverage.

- Tear film deficiencies.

- Immune-mediated keratopathies; for example, chronic superficial keratitis (rare in cats).

- Secondary to other ocular disorders; for example, glaucoma, uveitis, endothelial degeneration or dystrophy.

Diagnostic approach to corneal ulcers

A systematic diagnostic work-up is essential to identify underlying or contributing factors, and to guide appropriate therapeutic planning.

Recommended evaluations, where not contraindicated, include complete examination of the corneal surface and adnexa to look for any eyelid or eyelash abnormalities such as entropion, ectropion, distichiasis or trichiasis; Schirmer tear testing and tear film break-up time to identify any tear film abnormalities; fluorescein staining to identify corneal ulcers by adhering to the damaged cornea; and assessment of the bulbar surface of the third eyelid following instillation of a topical local anaesthetic to detect the presence of any foreign bodies.

Rose Bengal staining may be employed to identify devitalised corneal epithelial cells; however, clinicians should note that this stain can cause marked ocular irritation. Cytological examination of corneal or conjunctival samples can help determine the presence and type of inflammatory cells or microorganisms. In addition, samples obtained by swab should be submitted for aerobic and anaerobic culture to guide targeted antimicrobial therapy.

For a detailed examination of feline eye, see “Corneal ulcers in dogs” (Willard and Stavinohova, 2024).

Corneal ulcers in cats differ significantly from those seen in dogs. Unlike the classic spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects commonly encountered in dogs, such lesions are not recognised in cats (Hartley, 2010). Corneal ulcers in cats should never be treated by anterior stromal puncture (grid or punctate keratotomy), as this often leads to corneal sequestrum formation (Andrew et al, 2016).

Treatment of uncomplicated superficial feline corneal ulcers is primarily medical and aims to promote epithelial healing while minimising discomfort and preventing secondary infection. Management typically includes topical antibiotic therapy guided by corneal cytology or culture (if applicable), topical cycloplegics, frequent ocular lubrication and systemic analgesia such as NSAIDs or gabapentin.

Feline corneal ulcers that do not heal within seven days are generally classified as non-healing ulcers (Rujirekasuwan et al, 2025; Figures 1a and 1b). These cases should prompt investigation for underlying predisposing factors, including FHV-1 infection, brachycephalic conformation, ongoing mechanical trauma (such as entropion, foreign bodies or increased exposure) and age-related delays in epithelial regeneration in older cats (Maggs, 2018; Rujirekasuwan et al, 2025). Those ulcers usually heal after removal of the causative agent and standard treatment. The use of a bandage contact lens can be particularly beneficial in brachycephalic cats or in cases associated with eyelid conformational abnormalities, as it enhances corneal comfort, reduces pain and supports epithelial repair (Maggs, 2018).

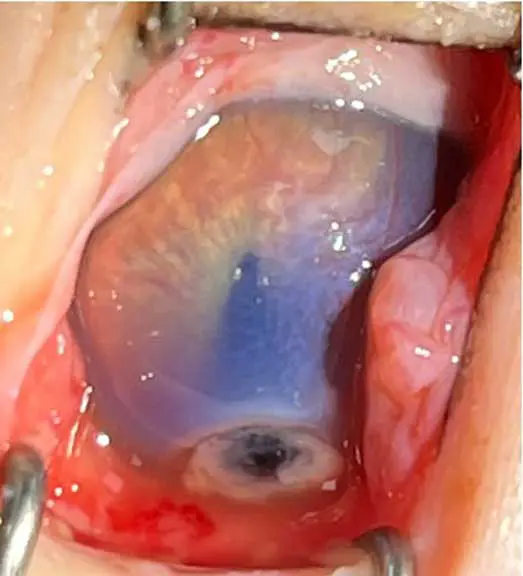

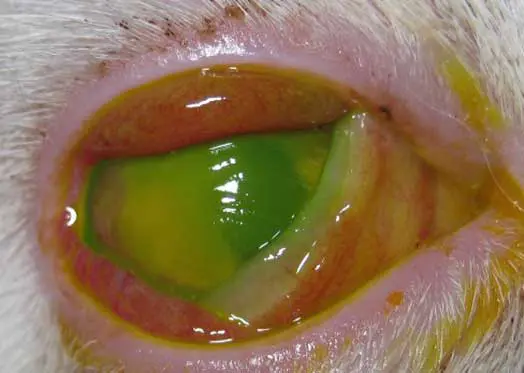

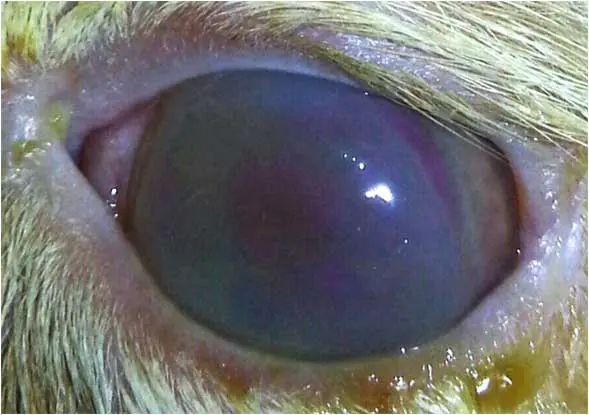

Corneal ulcers are considered complicated when infection is present (Figure 2) or when deeper stromal involvement occurs (Figure 3). If keratomalacia (corneal melting) is present, prompt and aggressive treatment is critical to preserve globe integrity (de Bustamante et al, 2018; Figure 4).

Management typically includes intensive topical antimicrobials, ideally guided by corneal cytology, culture, and sensitivity testing (Hartley, 2010), anticollagenase therapy (such as autologous or heterologous serum, N-acetylcysteine, or EDTA), lacrimomimetics, and topical cycloplegics to control secondary reflex uveitis (Hartley, 2010). Systemic NSAIDs and/or gabapentin should be administered, where appropriate, to aid in pain management. Ocular protection using an Elizabethan collar is essential to prevent self-trauma, and a quiet controlled environment should be advised during treatment. Corneal cross-linking may be considered as an adjunctive therapy in cases of active corneal melting to improve stromal stability. Surgical intervention should be promptly considered if medical management is ineffective, if significant stromal loss (typically exceeding 50%) or an imminent risk of globe perforation is present.

Surgical options include conjunctival grafts (Figure 5), corneolimbal-conjunctival transposition (CCT) or other grafting techniques or keratoplasty to provide tectonic support and facilitate corneal healing (Maggs, 2018; Telle and Betbeze, 2022). A descemetocele is characterised by complete loss of the corneal epithelium and stroma with only Descemet’s membrane remaining intact. This condition requires emergency referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist for corneal repair surgery, as a high risk of imminent corneal perforation exists. The referring veterinarian should provide systemic analgesia prior to referral (Figure 6).

FHV-1

Feline herpesvirus is a major cause of ocular and upper respiratory disease – particularly in kittens.

Acute infection produces “cat flu” signs such as conjunctivitis, keratitis and rhinotracheitis (Andrew et al, 2016). Unlike calicivirus, FHV-1 is a true corneal pathogen and can cause serious complications, including symblepharon from limbal stem cell damage, which is irreversible. Diagnosis is primarily established through clinical evaluation, with PCR analysis of conjunctival or oropharyngeal swabs employed for aetiological confirmation (Thiry et al, 2009). However, the sensitivity of PCR in this context may be limited, and false-negative results are frequently reported. Consequently, negative PCR findings should be interpreted with caution and in conjunction with clinical signs and epidemiological information.

Following infection, around 80% of cats become lifelong carriers, with the virus persisting in the trigeminal ganglia. Stress or immunosuppression may trigger recrudescence, leading to recurrent corneal ulceration when the virus damages the epithelium overlying corneal nerve endings (Andrew et al, 2016).

Characteristic lesions include (Thiry et al, 2009; Andrew et al, 2016) the following.

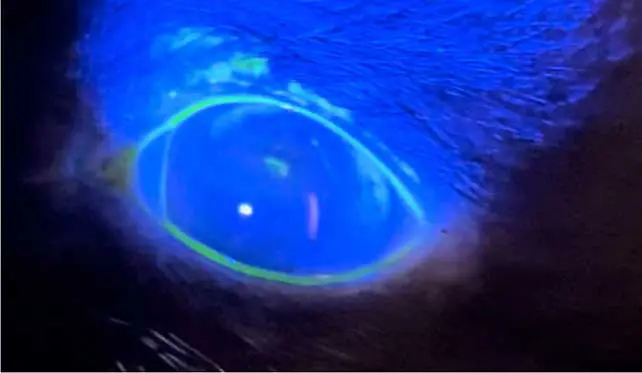

- Dendritic ulcers: pathognomonic for feline herpesvirus infection, following the pattern of trigeminal nerve endings within the cornea. They are best detected using Rose Bengal staining, as viral damage disrupts mucins and epithelial cell membranes before true ulceration occurs. This makes Rose Bengal more sensitive for identifying early or atypical herpes lesions, where the epithelium may remain intact but the cells are devitalised or mucin deficient. However, fluorescein staining remains a useful complementary test, as it highlights areas of epithelial disruption (Figure 7).

- Geographical ulcers: progressions of dendritic ulcers, larger and usually slower to heal (Figure 8).

- Metaherpetic stromal keratitis: an immune-mediated condition presenting as a vascular keratitis.

- Chronic sequelae include eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis, corneal sequestra and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS).

Treatment during the acute phase involves antivirals such as topical ganciclovir 0.15% applied every four hours, or systemic famciclovir.

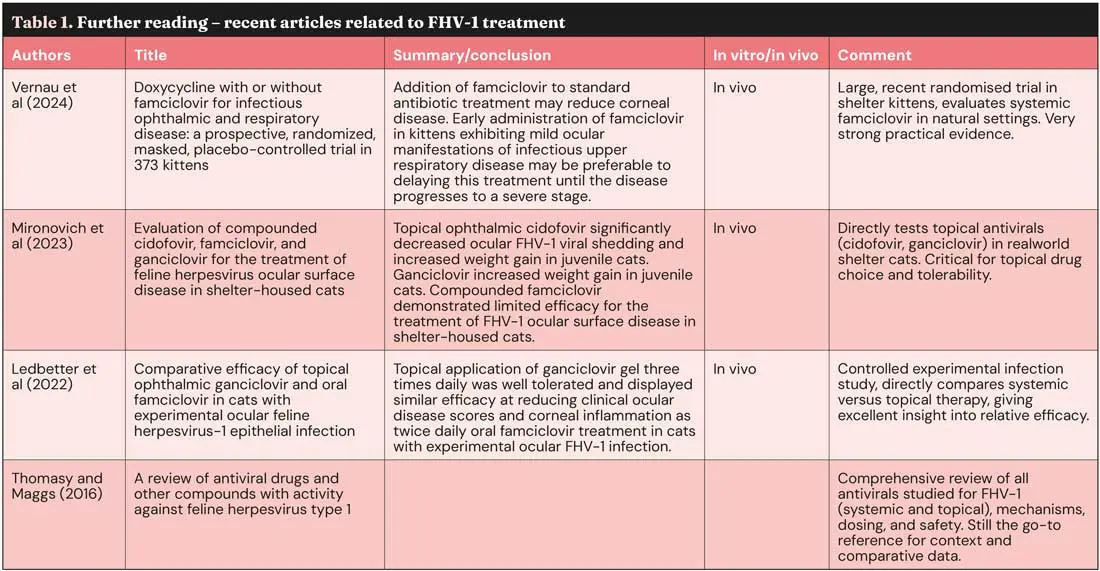

Famciclovir itself has no antiviral activity; it must be first metabolised to penciclovir.However, cats perform this metabolic activation very poorly, which means the appropriate dose of famciclovir can vary. The current recommendation is to start with a dose of 90mg/kg twice daily. Supportive care with topical artificial tears, cycloplegics, antibiotics and oral analgesia is often required (Maggs, 2005). For stromal or immune-mediated non-ulcerative keratitis, topical immunomodulators (corticosteroids or ciclosporin) should be used in combination with antiviral therapy and topical lacrimomimetics, with careful monitoring for the development of corneal ulcers (Table 1).

FHV-1 infection is not typically regarded as an emergency condition and can generally be managed within first opinion practice. However, given the diagnostic challenges associated with this disease, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion and consider referral when clinical signs are atypical, when concurrent ocular pathology is suspected, or when patients fail to respond to appropriate initial therapy.

Feline corneal sequestration

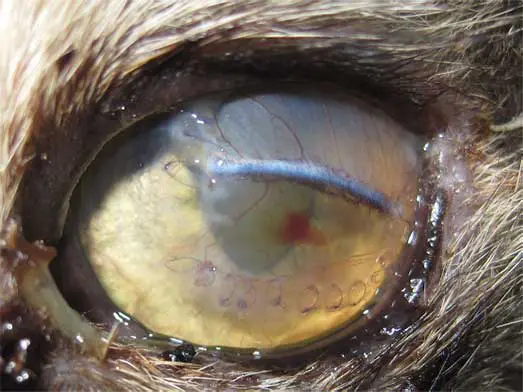

Corneal sequestra (Figure 9), also known as corneal necrosis or cornea nigrum, occur almost exclusively in cats and represent the cornea’s response to chronic insult (Graham et al, 2017; Multari et al, 2021). They are usually unilateral, but may be bilateral, and are strongly associated with FHV-1 infection, entropion, KCS, chronic exposure keratitis or poor tear film quality.

Certain breeds – particularly the Persian, Himalayan, Birman and Burmese – are predispose, although the underlying defect is unclear and may relate to brachycephalic skull conformation (Graham et al, 2017; Maggs, 2018). The condition begins as a brown discolouration deep within the corneal stroma that gradually enlarges and darkens, eventually breaching the epithelium to form a well-demarcated raised plaque. Once ulceration occurs, pain, vascularisation and corneal oedema develop. Small defects can be addressed with a bandage contact lens and supportive medical treatment (Maggs, 2018; Multari et al, 2021).

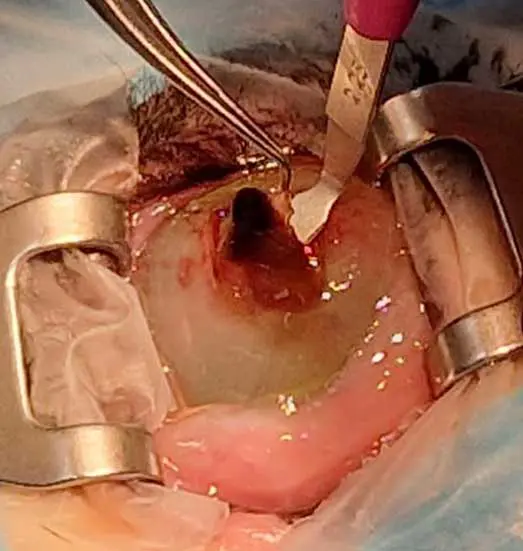

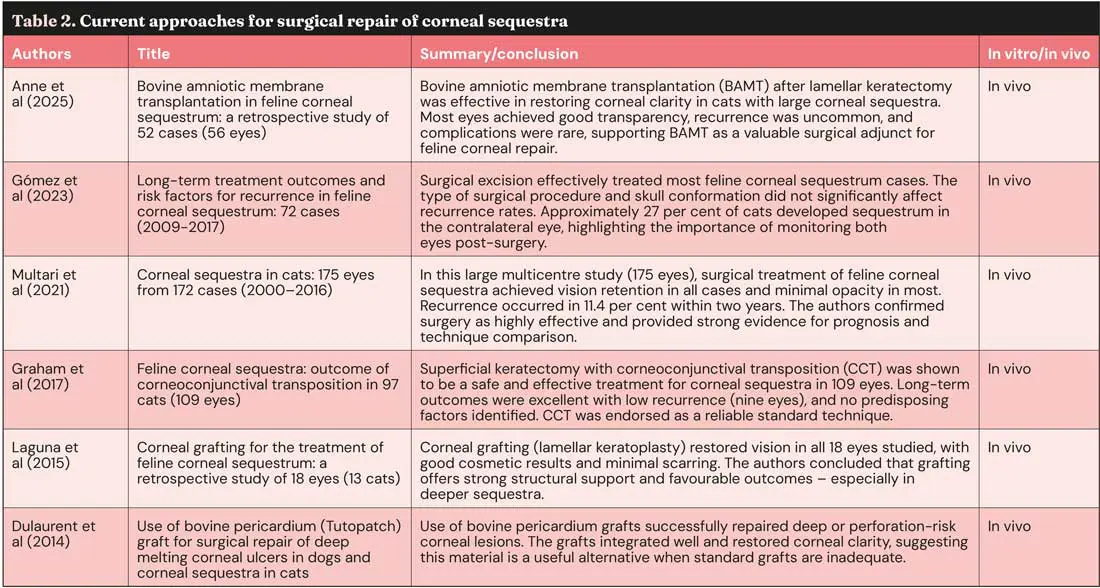

Some sequestra may eventually slough spontaneously, but this process is prolonged, painful, and carries a risk of infection or even perforation. Management involves medical treatment addressing any underlying pathology, with definitive treatment being usually surgical – most often via superficial keratectomy (Figure 10) with CCT (Figure 11) or other corneal grafting techniques or keratoplasty (Table 2).

This condition typically warrants referral, as definitive management often requires specialised corneal surgery and a comprehensive evaluation to identify and address any concurrent ocular pathology. Prior referral medical treatment includes topical antibiotic therapy guided by corneal cytology or culture, topical cycloplegics, frequent ocular lubrication and systemic analgesia such as NSAIDs or gabapentin.

Exposure keratitis

Corneal ulceration is a recognised complication in cats following sedation or general anaesthesia – particularly when agents such as ketamine are administered as a constant rate infusion. Reduced blink reflex and diminished tear production during anaesthesia compromise the protective tear film, leaving the corneal epithelium vulnerable to desiccation and mechanical trauma (Haubrich et al, 2025). Case reports and experimental studies demonstrate that tear production can remain significantly decreased during and immediately after anaesthesia, increasing the risk of superficial or even deep corneal ulcers (Haubrich et al, 2025). Protective measures, including ocular lubrication with ointments or gels throughout the peri-anaesthetic period, are essential to maintain corneal hydration and reduce the risk of ulceration. Cats with pre-existing ocular surface disease, brachycephalic cats or reduced baseline tear production are particularly susceptible, highlighting the importance of careful monitoring and proactive corneal protection during anaesthesia (Thenhaus-Schnabel et al, 2023).

Neurogenic keratitis and KCS in cats

Neurogenic keratitis in cats can be classified as either neuroparalytic or neurotrophic.

- Neuroparalytic keratitis occurs secondary to facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) paralysis, leading to incomplete blink function and subsequent exposure keratitis with corneal ulceration.

- Neurotrophic keratitis results from trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) dysfunction, causing loss of corneal sensation. Without sensory input, lacrimal reflex stimulation is reduced, leading to severe corneal drying and rapid ulcer formation.

KCS of autoimmune origin, as seen in dogs, is not recognised in cats. In this species, FHV-1 is considered the primary cause of KCS, often following chronic or recurrent viral keratitis. Effective management of neurogenic keratitis and KCS in cats, regardless of aetiology, relies on the appropriate selection and use of ocular lubricants with antibiotic therapy added when indicated (Haubrich et al, 2025).

In most cases, these conditions can be managed successfully in first opinion practice. Referral should be considered if adequate ocular comfort cannot be achieved or if concurrent ocular pathology is suspected.

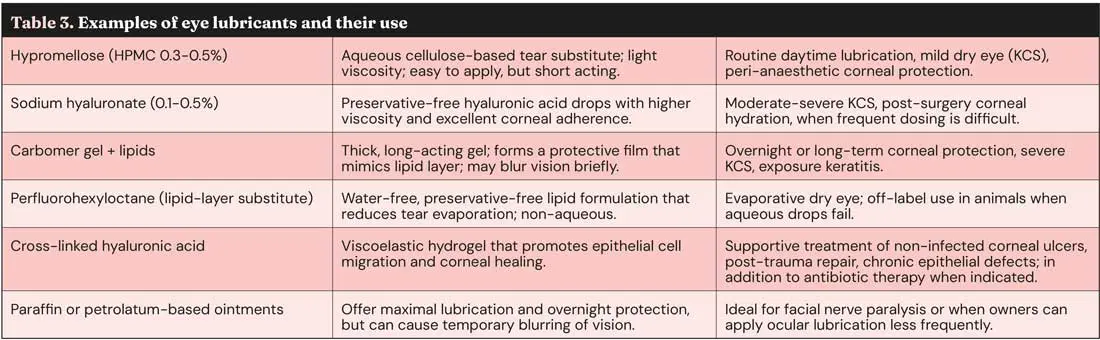

Choosing ocular lubricants in cats

A wide range of ophthalmic lubricants is available, varying in viscosity, formulation and duration of effect.

Selection should be guided by the severity of tear film deficiency, patient compliance and frequency of application. Many of these products are human formulations used off label in animals (Table 3).

Eosinophilic keratitis

Eosinophilic keratitis is an immune-mediated corneal disease most commonly seen in young to middle-aged cats. It may present unilaterally or bilaterally, and is characterised by distinctive white to pink, plaque-like deposits within the superficial corneal stroma and epithelium, typically starting in the dorsolateral cornea before potentially spreading to involve the entire surface (Figure 12). Superficial ulcers may occur due to inflammatory infiltrates and epithelial loss. Diagnosis is primarily based on the characteristic clinical appearance and confirmed cytologically by the presence of eosinophils and mast cells, often accompanied by neutrophils. Although the exact trigger is unknown, eosinophilic keratitis may represent a manifestation of the eosinophilic granuloma complex or can be associated with FHV-1 infection.

Treatment involves topical corticosteroids and/or ciclosporin; the latter can cause local drug reaction. The authors also recommend the addition of topical antivirals and antibiotics at the beginning of treatment. In cases where topical steroids are contraindicated or poorly tolerated, systemic corticosteroids may be considered (Maggs, 2018). Megestrol acetate should be avoided due to significant side effects (Hodges, 2005; Spiess et al, 2009). Recurrence is common – particularly on a seasonal basis.

Eosinophilic keratitis does not usually require referral and can generally be managed within first opinion practice once the diagnosis has been confirmed.

Referral should be considered in cases that fail to respond to appropriate medical therapy or when the clinical presentation is atypical.

Bullous keratopathy

Also referred to as acute corneal hydrops, bullous keratopathy is an uncommon but distinctive corneal condition observed primarily in young cats (Figure 13). The onset is typically acute, and while the disease often presents bilaterally, it may initially affect only one eye.

The underlying pathophysiology involves endothelial dysfunction, allowing aqueous humour to leak through the compromised corneal endothelium into the stroma, leading to stromal fluid accumulation (corneal oedema). As the stroma becomes saturated, subepithelial fluid pockets form, resulting in the development of epithelial bullae or blisters, which may rupture and cause discomfort or secondary ulceration (Pattullo, 2008).

Management of bullous keratopathy aims to reduce corneal oedema and protect the corneal surface. Topical hypertonic saline (5% sodium chloride) is commonly used to draw fluid from the cornea and reduce stromal swelling. Adjunctive therapy includes topical antibiotics, cycloplegics, autologous or heterologous serum, ocular lubricants to support epithelial healing, and systemic analgesia. In cases where medical therapy is insufficient or bullae are extensive, a third eyelid flap should be placed (Gellat, 2021). Additional surgical options include thermokeratoplasty or conjunctival grafting techniques.

Identification and management of any underlying endothelial disease or inflammatory trigger are essential to prevent recurrence and chronic corneal changes (Pattullo, 2008; Leis and Sandmeyer, 2023). Because bullous keratopathy is painful and can worsen quickly, referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist is recommended.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (20 January 2026), Volume 56, Issue 3, Pages 6-12

Zuzana Klimova graduated from the University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences in Brno, Czech Republic, in 2021. After moving to the UK, she completed a rotating internship and subsequently worked in a busy general practice in Scotland, where she developed a strong interest in ophthalmology. Zuzana is studying towards a postgraduate certificate in ophthalmology and works in a referral clinic in northern England.

Renata Stavinohova is an EBVS European and RCVS-recognised specialist in veterinary ophthalmology, and the founder and chief executive of VetSEES. She graduated from the University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences in Brno, Czech Republic, in 2008, where she also completed a PhD. She then undertook several years of specialist training in the UK, gaining the BSAVA Postgraduate Certificate in Small Animal Ophthalmology and becoming a diplomate of the European College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists (ECVO). Renata has worked across several UK veterinary specialist centres as a consultant ophthalmologist, including leadership roles as head of ophthalmology, developing extensive clinical expertise alongside strong managerial experience. At VetSEES, she combines clinical work with service leadership to deliver high-quality, evidence-based ophthalmology care for pets and a responsive, collaborative service for referring vets. Alongside her clinical practice, Renata serves as chairperson of the scientific committee for the ECVO and is actively involved in teaching and mentoring future veterinary ophthalmology specialists.

References

- Andrew SE (2016). Ocular manifestations of feline herpesvirus, J Feline Med Surg 3(1): 9-16.

- Anne J, Cathelin A and Augsburger A-S (2025). Bovine amniotic membrane transplantation in feline corneal sequestrum: a retrospective study of 52 cases (56 eyes), Vet Ophthalmol, online ahead of print.

- De Bustamante MGM, Good KL, Leonard BC et al (2018). Medical management of deep ulcerative keratitis in cats: 13 cases, Vet Ophthalmol 21(3): 220-230.

- Dulaurent T, Azoulay T, Goulle F et al (2014). Use of bovine pericardium (Tutopatch) graft for surgical repair of deep melting corneal ulcers in dogs and corneal sequestra in cats, Vet Ophthalmol 17(2): 91-99.

- Gelatt KN, Ben-Shlomo G, Gilger BC et al (2021). Veterinary Ophthalmology: Two-Volume Set (6th edn), Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken.

- Gómez AP, Mazzucchelli S, Smith K and de Lacerda RP (2023). Long-term treatment outcomes and risk factors for recurrence in feline corneal sequestrum: 72 cases (2009–2017), Vet Record 193(3): e2783.

- Graham KL, White J and Billson F (2017). Feline corneal sequestra: outcome of corneoconjunctival transposition in 97 cats (109 eyes), J Feline Med Surg 19(6): 710–716.

- Hartley C (2010). Treatment of corneal ulcers: what are the medical options?, J Feline Med Surg 12(5): 389-397.

- Haubrich KN, Leis ML, Levitt SM et al (2025). The impact of general anesthesia on feline aqueous tear production and the feline corneal epithelium, J Feline Med Surg 27(11): 1098612X251386135.

- Hodges A (2005). Eosinophilic keratitis and keratoconjunctivitis in a 7-year-old domestic shorthaired cat, Can Vet J 46(11): 1,034-1,035.

- Laguna F, Leiva M, Costa D et al (2015). Corneal grafting for the treatment of feline corneal sequestrum: a retrospective study of 18 eyes (13 cats), Vet Ophthalmol 18(4): 291–296.

- Ledbetter EC, Badanes ZI, Chan RX et al (2022). Comparative efficacy of topical ophthalmic ganciclovir and oral famciclovir in cats with experimental ocular FHV-1 epithelial infection, J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 38(5): 339-347.

- Leis ML and Sandmeyer LS (2023). Diagnostic ophthalmology, Can Vet J 64(11): 1,075-1,076.

- Maggs DJ (2018). In Maggs DJ, Miller PE and Ofri R (eds), Slatter’s Fundamentals of Veterinary Ophthalmology (6th edn), Elsevier, St. Louis.

- Maggs DJ (2005). Update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of feline herpesvirus type 1, Clin Tech in Small Animal Pract 20(2): 94-101.

- Mironovich MA, Yoon A, Marino ME et al (2023). Evaluation of compounded cidofovir, famciclovir, and ganciclovir for the treatment of feline herpesvirus ocular surface disease in shelter-housed cats, Vet Ophthalmol 26(Suppl 1): 143-153.

- Multari D, Perazzi A, Contiero B et al (2021). Corneal sequestra in cats: 175 eyes from 172 cases (2000–2016), J Small Animal Pract 62(6): 462-467.

- Pattullo K (2008). Acute bullous keratopathy in a domestic shorthair, Can Vet J 49(2): 187-189.

- Rujirekasuwan N, Sattasathuchana P, Sritrakoon N and Thengchaisri N (2025). Recurrent vs. nonrecurrent superficial non-healing corneal ulcers in cats: a multifactorial retrospective analysis, Animals 15(14): 2,104.

- Spiess AK, Sapienza JS and Mayordomo A (2009). Treatment of proliferative feline eosinophilic keratitis with topical 1.5% cyclosporine: 35 cases, Vet Ophthalmol 12(2): 132-137.

- Telle MR and Betbeze C (2022). Corneal surgery in the cat: diseases, considerations and surgical techniques, J Feline Med Surg 24(5): 429-441.

- Thenhaus-Schnabel M, Bilotta T, Watte C and Levionnois OL (2023). Bilateral corneal ulceration in a cat after general anaesthesia, Vet Rec Case Rep 11: e663.

- Thiry E, Addie D, Belák S et al (2009). Feline herpesvirus infection. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management, J Feline Med Surg 11(7): 547-555.

- Thomasy SM and Maggs DJ (2016). A review of antiviral drugs and other compounds with activity against feline herpesvirus type 1, Vet Ophthalmol 19(Suppl 1): 119-130.

- Vernau KM, Kim S, Thomasy SM et al (2024). Doxycycline with or without famciclovir for infectious ophthalmic and respiratory disease: a prospective, randomized, masked, placebo-controlled trial in 373 kittens, J Feline Med Surg 26(11): 1098612X241278413.

- Willard T and Stavinohova R (2024). Corneal ulcers in dogs, Vet Times 54(30): 12-17.