12 Nov 2018

Otitis externa and media in canine and feline patients

Diana Ferreira discusses available treatment options and management strategies for both outer and middle ear inflammation.

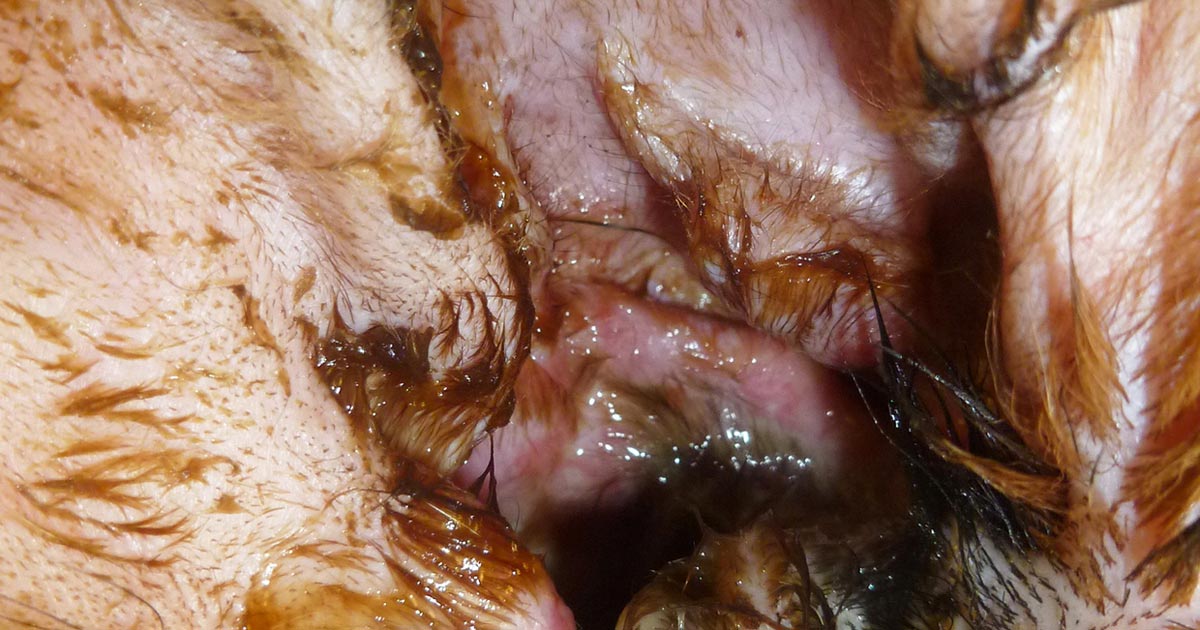

Figure 2. Ulceration of the external ear with an abundant amount of purulent discharge from the right ear of a dog with Pseudomonas aeruginosa otitis externa.

Approximately 20% of all canine patients – and between 4% to 7% of feline patients – have some type of ear disease, with one of the most frequent veterinary consult complaints being otitis externa (OE).

In the vast majority of otitis cases, the infections that occur are secondary to pre-existing factors, such as inflammation caused by allergic or parasitic diseases, the presence of foreign bodies, obstruction by masses or ceruminoliths, or endocrine conditions such as hypothyroidism.

The successful management of OE is dependent on the results of a thorough otoscopic and cytologic examination, and identification of the primary factors that initiated the otitis.

Otitis media (OM) is a common disease process that can go unrecognised. It usually occurs as an extension of external ear disease and can occur secondary to chronic OE in up to 50% of cases. OM can also occur in approximately 16% of acute OE cases and represent a potential cause of OE treatment failure. OM is challenging to diagnose because the presenting signs are usually similar to those of OE and cannot be distinguished in the absence of additional clinical signs, such as facial nerve dysfunction, for example.

In contrast to dogs, OM in cats most often results as a sequela of respiratory disease or due to the presence of inflammatory polyps in the ear (Figure 1).

OE management strategies

Bacterial and yeast infections of the ear canals are secondary problems in most cases of OE. Treatment of the infection only, without dealing with the underlying causes, can likely result in recurrence of the infection. In general, the management of OE involves ear cleaning, control of the secondary infections, control of inflammation and, as much as possible, control of the primary causes.

The cytological evaluation of the material obtained from the ear canal is a diagnostic test that is considered mandatory in the management of OE cases. It gives quick and very useful information. It will determine the presence and type of infectious organisms, as well as differentiate an infection from an overgrowth. The results of the cytology will help in the empirical selection of topical therapy. If a culture is performed, the culture results should be compared for compatibility with the cytology results.

Culture and sensitivity is recommended when chronic or recurrent OE and/or OM is present, rod-shaped bacteria are found on cytology or previous antibiotic therapy has failed, despite appropriate empirical therapy.

In most OE cases, the control of secondary infections can only be achieved with topical therapy. Unless the ear canal epithelium is extensively eroded or ulcerated, systemic antimicrobials are unlikely to achieve therapeutic concentrations within the fluid and waxy exudates of the external canals in which the infectious organisms are harboured. In contrast, the middle ear contains a highly vascular mucous membrane lining, which may allow for better diffusion of drugs from the vascular compartment to the bulla space.

Ear cleaning

Ear cleaning is the first step in the management of any ear disease and should be included in every case of OE. Ear cleaning removes microorganisms, inflammatory mediators and cerumen. Cleaning disrupts the biofilm that may harbour and promote the proliferation of organisms, and allows medication to come into good contact with the ear tissue lining.

Purulent discharges may inactivate topical medications applied in the ear canal and dried wax can irritate the ear further. Effective ear cleaning is, therefore, important to allow penetration of drugs. Also, it allows the proper assessment of the integrity of the tympanic membrane.

Ear cleaners can be divided into two categories:

- Ceruminolytic ear cleaners – these are more effective in removing wax. Diocytl sodium sulfosuccinate, calcium sulfosuccinate, urea or carbamide peroxide are potent ceruminolytic cleaners. They disrupt the integrity of the cerumen by inducing lysis of the squames. Other ingredients include organic oils and solvents that soften and loosen cerumen – such as butylated hydroxytoluene, cocamidopropyl betaine, glycerine, lanolin, propylene glycol and squalene.

- Aqueous-based ear cleaners are more useful in removing exudates/biofilm.

Ceruminolytics should not be instilled if the tympanic membrane is ruptured, except for squalene, which has been shown to be non-ototoxic.

Both categories tend to be formulated with antimicrobial ingredients, including chlorhexidine, acetic acid, boric acid, salicylic acid and phytosphingosine. Ear cleaners may also contain trisEDTA – an ingredient that potentiates the effect of antimicrobials. TrisEDTA chelates metal ions in bacterial cell walls, therefore increasing the permeability to various antibiotics and antimicrobials – enhancing the susceptibility of the bacteria to these other ingredients.

Regular cleaning is extremely important in the long-term care of dogs and cats prone to external ear disease as cleaning controls cerumen and microbial populations.

Topical therapies

The vast majority of veterinary products available for the treatment of OE contain a combination of an antibiotic, antifungal and glucocorticoid.

It should be noted the majority, if not all, of the available combination products are not indicated for use in the presence of a perforated eardrum due to the concern for ototoxicity.

The choice of an empirical antibiotic should be based on the cytological findings, and first line antibiotics should be the first choice.

In the author’s opinion, these include:

- Fusidic acid: has a good Gram-positive spectrum, but is not effective for Gram-negatives.

- Polymyxin B: has a good Gram-positive spectrum and good anti-Pseudomonas effects. It is inactivated in purulent debris.

The author would consider the following list as second line antibiotics, and their use should ideally always be based on culture and sensitivity testing:

- Fluoroquinolones (enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin): have good activity against a wide range of bacteria – especially Gram-positive and Gram-negative. Off-licence use of injectable fluoroquinolones mixed with sterile saline or trisEDTA have been employed where the licensed veterinary products are deemed unsafe due to damage to thetympanic membrane. These antibiotics are, therefore, considered non-ototoxic.

- Aminoglycosides: neomycin (good Gram-positive spectrum, does not cover Pseudomonas), gentamicin (excellent Gram-positive spectrum, covers 50% to 60% of Pseudomonas) and framycetin (good Gram-positive spectrum, poor for Pseudomonas, good for other Gram-negatives).

- Florfenicol: included in a long duration of effect product. It has good activity against Gram-positive Staphylococcus and Enterococcus species, and Gram-negative bacteria such as Proteus species. It has very limited activity against Pseudomonas species. It is a product that requires the ear to be cleaned and dried prior to its administration, and ear cleaners cannot be used between treatments. It exerts its action over prolonged periods (weeks).

In large-breed dogs, the number of drops recommended may have to be adjusted to the length of the ear canal. In these cases, the medication can be placed in a multidose vial, and the owner provided with a syringe and specific dose to more accurately apply the appropriate amounts of medication in the canal.

In cases of Malassezia otitis, topical preparations containing clotrimazol, miconazol or nystatin are appropriate; however, all of the products available for veterinary use contain an antibiotic, which is not necessary when bacteria are not involved in the otitis. The author commonly formulates a product for this purpose with a combination of 1% clotrimazol cream (off label) and injectable dexamethasone sodium phosphate (4mg/ml).

The most common ratio used is three parts miconazole to one part dexamethasone and the volumes adjusted to the size of the dog, used twice daily.

Pseudomonas OE

In the case of Pseudomonas ear infections, management can be challenging. Pseudomonas are intrinsically resistant to many antibiotics and, furthermore, can rapidly acquire additional resistances – especially with frequent topical antibiotic treatments. Also, biofilm production is relatively common in Pseudomonas otitis.

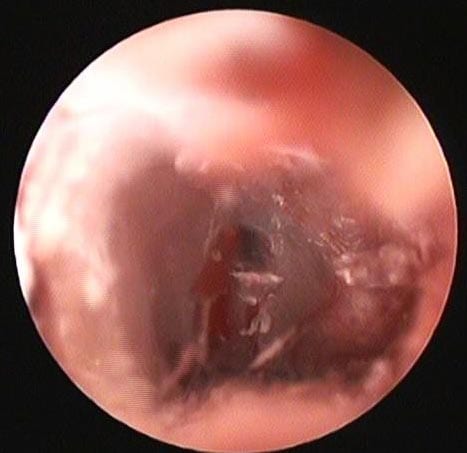

Clinically, Pseudomonas infections frequently present as an acute suppurative otitis, with a characteristic yellow/green malodorous suppurative mucoid discharge and associated with severe inflammation (Figure 2). The ears are often eroded or ulcerated and very painful (Figure 3). Eardrum perforation is commonly seen in these cases.

All the aforementioned characteristics warrant special diagnostic and therapeutic considerations for the successful management of Pseudomonas ear infections. Because of the likelihood of perforation of the tympanic membrane, advanced imaging with MRI or CT scans is recommended to determine if middle ear disease associated with a Pseudomonas infection exists.

Systemic glucocorticoids are usually of significant benefit because they rapidly reduce inflammation, exudation, pain, discomfort and proliferative changes. In severely proliferative/hyperplastic ears, prednisolone can be used at a starting dose of 1mg/kg/day for 10 to 15 days, then tapered according to the response to treatment.

All Pseudomonas otitis cases benefit from thorough ear flushing (see video below) under general anaesthesia for proper removal of the purulent discharge and disruption of the biofilm commonly present in these infections.

For home maintenance cleaning, ear flushes are also essential for a continuous removal of the purulent material.

TrisEDTA-based ear cleaners are very useful in Pseudomonas infections. TrisEDTA increases the permeability of bacterial cell membranes – principally Gram-negative bacteria – and, therefore, improves the antimicrobial sensitivity of biofilm-embedded bacteria. The topical antibiotic treatment option favoured by the author includes the off-label use of silver sulfadiazine 1% cream. This cream is well tolerated in cases with a ruptured tympanic membrane and can be applied directly into the ear canal, or diluted with water or trisEDTA.

Aqueous solutions of glucocorticoids, such as dexamethasone, are very useful to control the inflammation of the ear canal and, furthermore, are considered to be well tolerated within the middle ear. Glucocorticoids can be added to the antibiotic preparation solutions if a commercial combined product is not being used.

The management of Pseudomonas OE can last as long as three months or more. Rechecks should be frequent (every 10 days to 2 weeks) for monitoring of the infection progression, with otoscopic and cytological assessment, and monitoring of the inflammation of the ear canal.

Frequent ear flushes may be needed to help disrupt the biofilm formed by the bacteria and allow topical treatments to be effective. The treatment should be continued until the infection is resolved (negative cytology and cultures) and the inflammation in the ear canals is controlled.

Maintenance treatments with regular ear cleanings, along with a control of the inflammation with topical glucocorticoids, is imperative to prevent recurrences. Suitable ear flushes for maintenance therapy include those containing acetic acid or trisEDTA.

Pseudomonas OE occurs secondary to an underlying primary condition. To prevent recurrence of the disease, after therapy has resolved the infection, it is important to identify and manage the underlying primary disease.

OM management strategies

The first step in the management of OM is the assessment of the middle ear through advanced imaging such as CT or MRI. Radiography is not so sensitive for detection of material in the middle ear.

The imaging can help decide whether the ear can have a medical – rather than a surgical – management, in cases of irreversibly damaged ear canals. The prognosis for medical management is poor if extensive evidence exists of osteomyelitis of the bulla wall, or if changes are seen that suggest a middle ear mass.

Where medical management can be pursued, samples from the middle ear should be obtained for cytology and culture by using a tomcat urinary catheter.

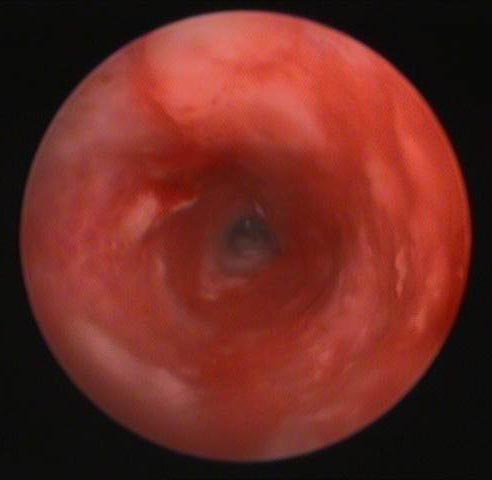

This same catheter can be used to perform a myringotomy when the tympanic membrane is not already ruptured (Figure 4).

Once the samples have been collected, the ear should be flushed with warmed saline. The mucoperiosteum that lines the tympanic bulla reacts to inflammation by producing mucus. This mucus traps and protects bacteria, and prevents the adequate penetration of topical medication.

Additionally, many enzymes are trapped in the mucoid secretions in the bullae and remain in contact with the mucoperiosteum, prolonging the disease. Ear flushing is, therefore, a critical part of management of an OM.

Once the ear has been cleaned, topical antibiotics can be infused into the bulla. The choice of antibiotic is based on the results of a culture and sensitivity panel, as well as on ototoxic potential. In general, aqueous formulations of fluoroquinolones (enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin), glucocorticoids, azoles and silver sulfadiazine appear to be well tolerated in the middle ear.

The use of systemic antibiotics in middle ear disease is controversial. Systemic antibacterial therapy for OM will rely on lower levels of antibiotics arriving in the middle ear haematogenously or through inflammatory cells. Because of the poor blood supply in the external ear canal and middle ear, limited diffusion of antibiotic to these areas exists.

Nevertheless, if a systemic treatment approach is pursued, the antibiotic should be chosen based on a culture and sensitivity panel. A four to eight-week treatment period may be needed for therapeutic success.

The use of corticosteroids in the management of OM is important as it reduces the intense inflammation and exudation of the middle ear, enhancing the ability of topically applied antibiotics to penetrate into the infected tissue. Aqueous topical corticosteroids may be infused into the middle ear or mixed with the topical antibiotic solutions.

It appears 0.15% chlorhexidine and trisEDTA-based flushes are well tolerated as cleaners for OM and should be used at least daily over the first two weeks of treatment. The frequency of cleaning should then be adjusted according to the amount of exudate obtained.

Topical antibiotics can be prescribed in the aqueous solution form for administration by the owners at home. They can be dispensed in a multidose vial, and the owner given a syringe and specific dosage to administer locally, or can be prepared as individual doses prepared in syringes. They can also be added to trisEDTA to facilitate their activity.

Proper monitoring of the progression of the middle ear disease is only done with repeated advanced imaging. When the repeated examination reveals a dry canal, and the cytology and culture are negative, topical and systemic treatments can be discontinued.

As in all cases of otitis, maintenance treatments with regular ear cleanings, along with a control of the inflammation with topical glucocorticoids, is imperative to prevent recurrences. Underlying primary diseases should always be identified and managed.

Medical therapy of OM can be successful in more than 75% of cases. Only a small number of chronic OM cases require a surgical approach despite proper medical therapy.

In summary

The successful management of OE is dependent on the results of a thorough otoscopic and cytological examination, and identification of the primary factors that initiated the otitis. In general, the management of OE involves ear cleaning, control of the secondary infections and control of inflammation.

In the case of Pseudomonas ear infections, management can be challenging due to an extensive antibiotic resistance profile, biofilm production and ear drum perforation.

A thorough diagnosis of OM requires the use of advanced imaging techniques. Samples should be obtained from the middle ear for cytology and cultures. Ear flushing is a critical part of management of an OM.