24 Mar 2020

Otitis externa – successful management and diagnostics

Ariane Neuber describes approaches to examining patients, underlying causative factors, therapy options and innovations.

Figure 1. The ear of a dog with atopic dermatitis and secondary Malassezia otitis, showing brown waxy otic discharge.

Surely not many days have passed in the lives of most small animal vets without seeing a case of ear disease. Many canine patients present to veterinary practices with ear disease day in, day out.

It is a very common issue and can be very painful for the patient, and frustrating for owners and vets alike. If the issue is not dealt with successfully, many owners lose faith in the attending vet and change practice.

Additionally, each episode of otitis predisposes the patient to further episodes, as the inflammatory changes make it more likely for microbial overgrowth to happen again.

In analogy to pruritus, otitis is just a clinical sign, not a diagnosis, and it is important to identify and address all the factors involved.

It is easy to underestimate the amount of pain associated with ear disease − particularly because dogs are programmed not to show their pain. However, the pain can severely impair the animal’s quality of life.

Additionally, every episode of otitis leaves the ear in a worse condition – with ceruminous gland hyperplasia, stenosis, malfunctioning self-cleaning mechanism and potential breach of the tympanic membrane.

In severe cases, repeated episodes of otitis can even lead to the need for surgery, with removal of the affected structures and loss of hearing for the dog.

Early intervention is, therefore, important – if not vital – to avoid a life of misery for everyone involved.

Approach

When presented with a patient with otitis (Figures 1 and 2), it is important to take a good history and perform a thorough examination. Cats are far less frequently affected – and most of this article refers mainly to dogs.

Little clues, such as episodes of pruritus, seasonality, alopecia and other dermatological signs; concurrent clinical signs, such as polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, vomiting and diarrhoea; exercise intolerance, the ear disease being unilateral, as opposed to bilateral; or recurrent pyoderma can all help identify the underlying disease that causes the patient to develop ear disease.

The approach will be similar to any dermatological patient. It is important to examine the whole patient, in case clues exist to a more generalised problem.

Otoscopy and cytology are vital to gain as much information as possible.

Otoscopy

Otoscopy is a very important part in the examination of patients with otitis.

Many patients with acute otitis are painful and otoscopy may need delaying until initial therapy has improved the situation. Otherwise, a danger exists that patients become head shy due to the pain associated with the examination, which will make future examinations – and, indeed, treatment at home – very difficult.

Patients who have had painful experiences may need sedating for a safe and thorough examination in the future.

Stenosis of the ear canal due to the inflammation in acute otitis can make visualisation difficult to impossible. A short course of glucocorticoids will help control the inflammation, “open” up the ear canal and make the patient more comfortable so it, hopefully, more readily allows this kind of examination to take place.

A good light source is important to be able to visualise the deeper structures of the ear – including the tympanic membrane – on examination. Medical and surgical otoscopes are available, as are video otoscopes (Figure 3) and digital otoscopes, which can be used to document the changes in the ear canal. This can be an important tool for client education.

A sterile cone is vital to avoid cross‑contamination between patients and, indeed, between the two ears of one patient. To achieve this, a sufficient number of cones must be available – and they need to be sterilised between uses by removing gross dirt, followed by either autoclaving them or using a proprietary endoscopic cleaner and sterilisation solution (Kirby et al, 2010).

To perform otoscopy, use a warmed-up cone and pull the pinnae gently up to stretch the ear canal during the examination. This facilitates reaching the vertical canal as comfortably as possible for the patient.

Good restraint of the dog is also important to avoid causing damage to the lining of the ear canal during the procedure.

The ear canal should be smooth – possibly with a small amount of earwax and some hair growth (with extensive breed variation) – and the tympanic membrane smooth, glistening and translucent in appearance.

Cytology

Most cases of otitis externa are complicated by microbial overgrowth.

Although commensal and transient organisms are normal in the ear canal and help protect the skin from pathogenic species, early inflammation leads to increased ceruminous and more watery secretions, which, in turn, is possibly implicated in microbial proliferation.

Normal cerumen contains IgA, IgG and IgM, free fatty acids and antimicrobial peptides – for example, cathelicidins – that make for an antimicrobial environment.

A normal ear canal has got an elevator-like self-cleaning mechanism, which removes sebum, organisms and trapped dirt, keeping the ear canal relatively clean. In ear disease, this self-cleaning mechanism is overwhelmed and no longer effective. Additionally, stenosis and fibrosis perpetuate the disease process.

As the microorganisms – both bacteria and yeast organisms – are important in perpetuating this process, their identification is very important. This can be done with cytology.

Cytology is probably the most important tool in the investigation of ear disease. With practice, it is relatively cheap, easy and quick to perform in-house, and gives an almost instant update of the status quo in each ear.

With slight modifications, it can usually even be performed in the most fractious and aggressive animals.

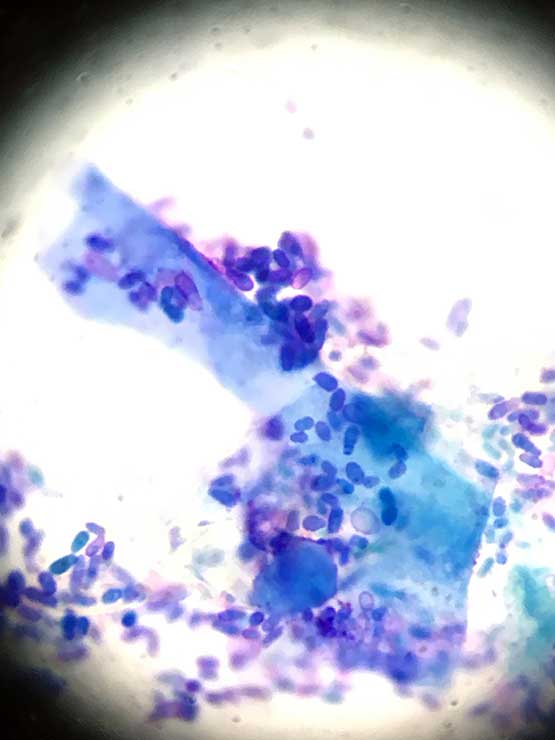

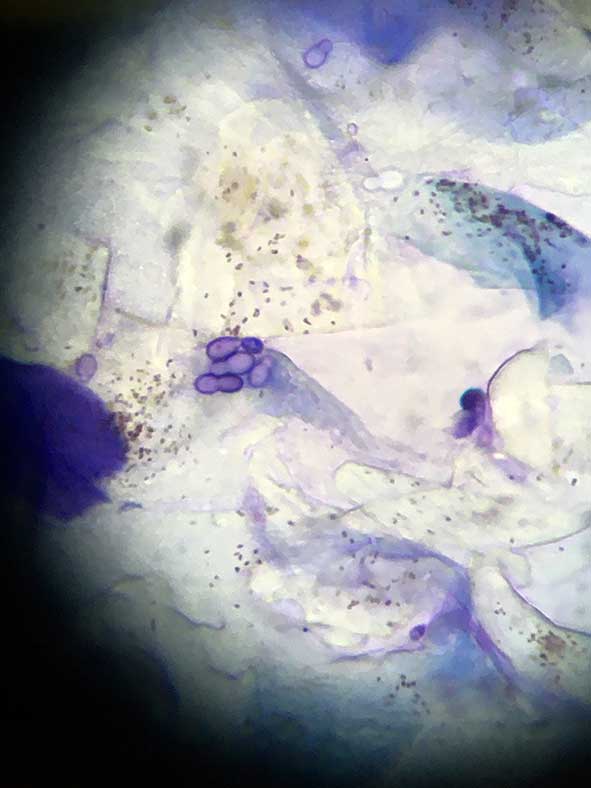

A cotton bud is gently introduced into the ear canal to obtain a sample of the otic discharge. This is then carefully rolled out on to a microscopic glass slide and prepared for microscopic examination. Avoid smearing the material, as this may disrupt the cells.

To save slides and time, it is possible to use the same slide for samples from both ears by using the side right next to the frosted end for the right ear and the opposite end for the left ear (or vice versa).

Lehner et al (2010) found substantial reproducibility for the results of successive swabs for cocci and rods, and moderate agreement for yeasts.

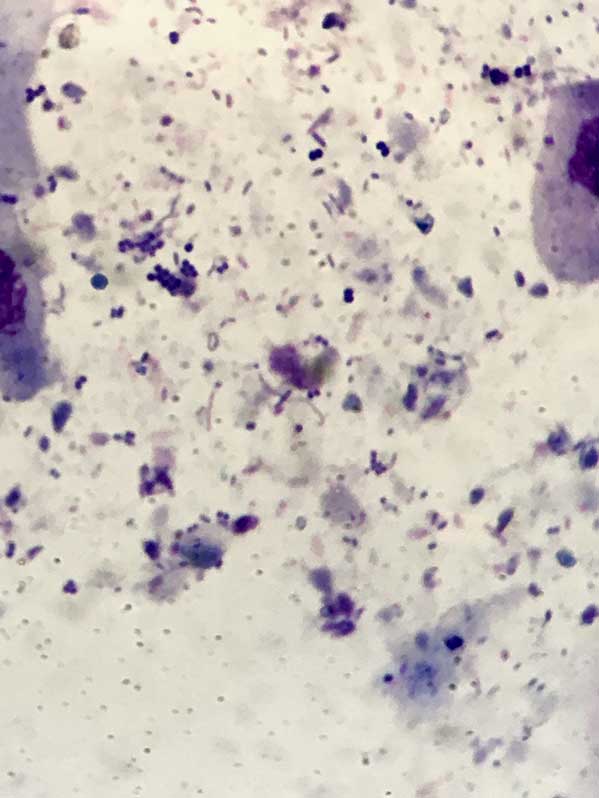

Most practices have Romanowsky-type staining sets in their laboratory. This type of stain does not allow the examiner to distinguish between Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms. However, most rods found in a ear are Gram-negative (one exception is, for example, Corynebacterium, which is rod shaped, yet a Gram-positive organism) and most cocci are Gram-positive.

Various methods have been described – and to some degree, they reflect personal preference. Waxy samples can be heat fixed, although Toma et al (2006) found this to not be necessary.

More purulent samples are dried and fixed with the fixing solution, before being immersed into the eosin red – followed by methylene blue – stains. Many dermatologists will simply use a drop of methylene blue on the sample, rinse, dry and examine the slide microscopically. This was supported by the study by Toma et al (2006).

Using exclusively a drop of blue stain will result in less cell detail visible; however, for most ear samples, it is time-saving and perfectly adequate. It also eliminates the risk of contamination of the stain pot (Duffield et al, 2015).

Once the sample has been stained and dried, a drop of immersion oil is applied, followed by a cover slip to reduce light beam scatter resulting in a blurry picture, and the slide is examined microscopically. Practitioners must make sure the distance between the eyepieces is comfortable for their face shape.

To achieve maximum resolution, the condenser is usually high (it can be adjusted by altering the height of the condenser to achieve good focus on a sharp object placed in the centre of the light source, while the light source is closed).

Having found an area on the slide with some purple stained material, this field is then examined more closely under higher magnification, eventually under the oil immersion lens if indicated.

Most important details to note are the type and number of cells (for example, keratinocytes and neutrophils) and microorganisms (Figures 4 to 6).

If rod-shaped bacteria are found, culture and sensitivity testing is indicated. Other indications are, for example, marked purulent discharge without any organisms, pyogranulomatous inflammation in the ear, or if a meticillin‑resistant staphylococci species – such as MRSA, meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) or meticillin‑resistant Staphylococcus schleiferi – are suspected.

Performing cytology for every case of otitis helps direct the choice of treatment and upholds antibiotic stewardship.

Advanced imaging

Diagnostic imaging may be required in some chronic cases of otitis, to determine whether the ear is salvageable by medical means.

Early intervention is, therefore, directed at avoiding reaching the stage where imaging and surgery may be needed.

Primary, predisposing, perpetuating and secondary factors

Otitis is a multifactorial disease. The underlying factors consist of predisposing, primary and perpetuating factors (Table 1), as well as secondary causes.

| Table 1. The primary, predisposing, secondary and perpetuating system | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Predisposing | Secondary | Perpetuating |

| Foreign body – for example, grass seed | Conformation – for example, stenotic ear (Shar Pei) | Yeast – for example, Malassezia pachydermatis | Changes to the ear canal – for example, ceruminous gland hyperplasia, epithelial migration breakdown, stenosis, mineralisation or ossification, or biofilm formation |

| Ectoparasites – for example, Demodex species, Otodectes cynotis | Hairy ear canal – for example, poodle | ||

| Allergic – for example, environmental or food allergy | Pendulous pinnae – for example, springer spaniel | Gram-positive bacteria – for example, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, enterococci, Corynebacterium | |

| Autoimmune – for example, pemphigus foliaceus, drug eruption | Treatment effects – for example, harsh cleaner, excessive cleaning, hair plucking | Changes to the middle ear – for example, ruptured eardrum, discharge in the middle ear, changes to the bony structure, biofilm | |

| Keratinisation disorder – for example, sebaceous adenitis | Excessive moisture – for example, swimmer’s ear | Gram-negative bacteria – for example, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli | |

| Endocrine – for example, hyperadrenocorticism, hypothyroidism | Obstruction in the ear canal – for example, polyp, neoplasia | ||

| Idiopathic – for example, juvenile cellulitis | |||

If they are not properly identified and addressed, it may be possible to resolve the acute infection; however, it is very likely the patient will relapse, often worse than before (for example, with a multi-resistant bug, such as Pseudomonas otitis or MRSP in the ear canal).

Primary factors

A number of factors are known to be the primary issue in ear disease. The most common is allergic skin disease. In some cases, the expression of the allergy is restricted to the ear alone.

Other primary factors are conditions such as a cornification defect, endocrine disease or a foreign body that can cause otitis in patients.

Predisposing factors

Predisposing factors are defined as factors existing prior to the onset of the disease that contribute to the development of the disease. On their own, they do not lead to clinical disease.

Examples are the anatomical structure of the ear – such as excessive hair growth in the ear canal (for example, poodles), a Shar Pei with congenitally very stenotic ear canals, or pendulous pinnae restricting airflow to the ear canal (spaniels’ ears are a good example).

Perpetuating factors

Factors that develop due to the otitis – and subsequently facilitate the occurrence of another episode of ear disease – are known as perpetuating factors. Among those factors are conditions such as ceruminous gland hyperplasia, stenosis of the ear canal, scarring hyperplasia of the ear canal, calcification and even ossification of the cartilage.

Secondary factors

The skin and ear canal are by no means sterile. A resident flora of bacteria, yeast organisms and other microbes are always present, forming the microbiome of that body region. Transient organisms can also be found.

Usually, the microbes are in a healthy balance with the host organism. However, under certain circumstances, the population of these organisms multiplies and clinical signs – such as discharge, malodour, pruritus and pain – are associated with the increase in microorganisms.

Some microorganisms – such as cocci, rods and yeasts – are secondary factors in the disease process. In acute otitis, overgrowth of one of the organisms is usually present.

When a high number of microorganisms (most commonly Malassezia species and S pseudintermedius; streptococci, Pseudomonas species, coliforms, Klebsiella species, Proteus species and Escherichia coli are less frequently cultured) overwhelms the ear canal, which lead to an inflammatory reaction and clinical signs of otitis.

Most staphylococci species (unless meticillin‑resistant) have a predictable pattern of antibiotic sensitivity. Rods are more erratic in this respect, which makes it important to identify the types of organisms involved and their resistance pattern, as this influences heavily the choice of therapy and prognosis. Cytology is vital in this decision-making process.

Ear cleaning

Epithelial migration keep healthy ears clean. Otitis overwhelms this self-cleaning mechanism as large amounts of otic discharge are formed in a diseased ear.

Cleaning – either at home or, in some cases, in the practice, depending of the severity of the disease – and the temperament of the patient and owner are important for a number of reasons:

- removal of microorganisms

- removal of allergens

- removal of small foreign bodies

- removal of debris harbouring organisms and shielding them from treatments

- visualisation of deep structures of the ear

- purulent material inactivates some antibiotics (for example, polymyxin B)

- some cleaners (for example, tromethamine‑ethylenediaminetetraacetate [Tris-EDTA]) enhance the action of certain antibiotics

Topical therapy

All sensitivity testing uses a breakpoint for serum concentrations; however, topical therapy can achieve much higher concentrations of active ingredients than systemic therapy ever can.

Often, despite bacteria tested as resistant to the antibiotic in the drops chosen empirically, they have already led to a good improvement before the culture results were available.

Using topical – rather than systemic – antibiotics is in the interest of antibiotic stewardship and should be used whenever possible. Newer preparations slowly release the active ingredients (usually a mix of an anti‑inflammatory, antibiotic and antifungal). These are very helpful in mild cases of otitis in nervous dog and can hopefully avoid these dogs becoming head shy in the future.

Another valid reason for using long-acting preparations are patients with unreliable owners, as using them elegantly circumvents one of the most pressing issues in otitis therapy – compliance.

Whenever topical medication is used, it is important to ensure the tympanic membrane is intact. This is particularly true for long-acting preparation, as they remain in the ear – and potentially the middle ear – for a long time.

If a lot of discharge is present, thorough cleaning – under sedation if needed – and visualisation are required.

Ototoxicity

Owners and vets fear potential signs of ototoxicity − particularly in cases where the status of the tympanic membrane cannot be ascertained.

In theory, ototoxicity is always possible whenever any substance reaches the middle and/or inner ear. No ear preparation is licensed for use if the tympanic membrane is compromised.

The substances most likely to reach the middle ear are:

- ear cleaner

- ear drops

- inflammatory cells and their by-products

- microorganisms and any of their secretions

- flushing solutions

In a clinical situation, ototoxicity is relatively uncommon. Nonetheless, it is worth warning the owner of this risk − particularly if in-practice cleaning is carried out and if the integrity of the tympanic membrane is unknown.

Clinicians need to be aware of substances more likely to cause problems and those that are deemed safe in the middle ear. Some substances – such as fluoroquinolones, squalene, Tris-EDTA, clotrimazole, miconazole and dexamethasone – are deemed relatively safe in the middle ear.

Ticarcillin, polymyxin B, neomycin, tobramycin and amikacin are potentially ototoxic in dogs with a ruptured tympanic membrane.

Systemic therapy

Systemic therapy is only useful in very select cases, as it is hard to achieve drug levels comparable to those achieved by topical medication.

Cases benefiting from systemic drugs include:

- ear mite infestations (selamectin, moxidectin spot-on or isoxazolines)

- otitis media (systemic antimicrobial therapy)

- patients with severe inflammation (systemic glucocorticoids) to provide analgesia and reduce swelling, as well as having an otoprotective effect

Rechecks

Regular repeat consultations are very important to achieve a successful long-term outlook for patients with otitis.

Acute otitis needs to be treated with appropriate medication, and it is important to follow-up the case clinically and with cytology.

In some cases, long-term cleaning may need to be performed until the self-cleaning mechanisms have regenerated.

To avoid relapses, the primary disease needs to be identified and managed. Dogs with relapsing otitis, particularly if a multidrug‑resistant strain of bacteria has been cultured, may benefit from referral to a dermatologist.

Summary

Cases of otitis are multifactorial and, therefore, need an integrated approach.

Additionally to dealing with the acute symptoms and infection, the primary disease and perpetuating factors need to be investigated and addressed. Otoscopy and cytology help collect information about the status of the ear canal, and nature of infection and inflammation.

Follow-up is vital and further tests, such as a dietary trial and allergy testing, may be needed to formulate a long-term strategy to avoid relapses. In most cases, some kind of analgesia and/or anti-inflammatory agent is required to deal with this painful condition.