15 Nov 2019

Niamh Clancy discusses common behaviours seen in companion animals and the use of scoring charts in veterinary practice.

Figure 3. A patient with abdominal discomfort in a hunched position.

It has been well documented that the recognition of pain in companion animals varies greatly between veterinary professionals (Dohoo and Dohoo, 1996).

Lascelles et al (1999) stated the age and sex of the veterinary surgeon can impact on the pain score he or she assigns to a patient – with a younger, female vet assigning a higher pain score than an older, male vet.

A 2004 questionnaire of RVNs’ attitudes towards pain scoring showed they assigned a higher pain score to all procedures compared to vets (Coleman and Slingsby, 2007). However, in this same questionnaire, 96% of nurses felt their knowledge could be enhanced further.

A range of types of pain score charts can be used to aid RVNs and vets in supplying a more objective pain assessment. These can, however, have limitations; it is, therefore, important veterinary professionals are aware of common pain behaviours in companion animals.

To assess and treat pain adequately, it is important to understand how pain is initiated.

Nociception is defined as the reception, conduction and processing of signals that leads to the perception of pain (Self, 2019).

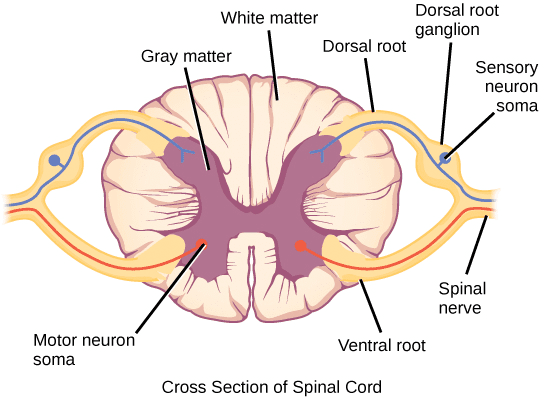

Pain signals move through five stages, eventually ending in the perception of pain; how this occurs is explained in Figure 1.

![Figure 1. How pain signals move through the body (adapted from Muir [2009]).](https://www.vettimes.co.uk/app/uploads/2019/10/LVS-CT-2019_Clancy_Fig1.png)

This information is then transformed into electrical signals, which are referred to as action potentials, and transmitted to the spinal cord by sensory afferent peripheral nerve fibres located in the dorsal root of the spinal nerves and sensory ganglia of the cranial nerves. The level of insertion at the spinal cord can be seen in Figure 2.

Once action potentials reach the spinal cord, they are modulated and can be either amplified or suppressed (Muir, 2009). Following this, bundles of neurons from the laminae of the dorsal horn convey nociceptive information to the brain; this is known as projection.

Finally, perception occurs in multiple specific areas of the brain. Within the brain, communication occurs via interneurons to produce an integrated response.

The understanding of pain pathways plays an important role in the treatment of pain in companion animals. If these pathways are fully understood, it can mean pain can be intercepted at different levels – leading to a more multimodal approach to analgesia; whether to be with the use of local anaesthetics or systemic opioids.

If left untreated, pain can lead to a multitude of issues that negatively affect the patient. Major side effects include:

It is important to remember all of these side effects can increase healing time and, therefore, increase the patient’s length of stay in the clinic or hospital.

Although a lot of time is spent discussing the negative side effects of pain and why this makes pain scoring important, it is also important to consider that pain scoring can also prevent veterinary professionals from overdosing the patient with analgesia.

Major negative side effects of overdosing with analgesia include (Kerr, 2007):

These common side effects make it apparent that both RVNs and vets should be aware of common pain behaviours seen in companion animals, and commonly used pain scoring scales.

Animals may not display outward behaviour, which is normally associated with pain when surrounded by humans or in a unusual environment (Muir and Gaynor, 2009).

Although, over time, some behaviours have been noted that have, classically, been indicative of pain in certain species, many factors can change these behaviours – such as age, breed, sex and the patient’s normal behaviour.

Panels 1 and 2 provide a list of pain behaviours commonly seen in companion animals; these lists are not exhaustive.

Dog:

Cat:

When assessing pain, it is important to consider what may be normal for each individual patient. Some behaviours may be due to stress caused by the patient being in an abnormal environment. Some behaviours are normal for one patient, but not for the others, such as vocalisation.

Additionally, also some pain behaviours can be associated with disease processes – a table of these can be found in Panel 3.

Pain scales are supposed to provide an objective and repeatable way of assessing pain, regardless of veterinary professionals’ subjective biases.

Unfortunately, vets and VNs tend to end up with an assessment that is subjective, categorical, and prone to misunderstanding and misinterpretation.

As aforementioned, patients may receive a varied pain score from one person to another, dependent on age, sex or job role.

With this in mind, the author suggests pain scales be used as a guide to the level of pain a patient feels, alongside the assessor’s own individual feeling.

In the author’s hospital, anaesthesia nurses frequently discuss a patient’s pain as a team to allow for multiple inputs and assessments.

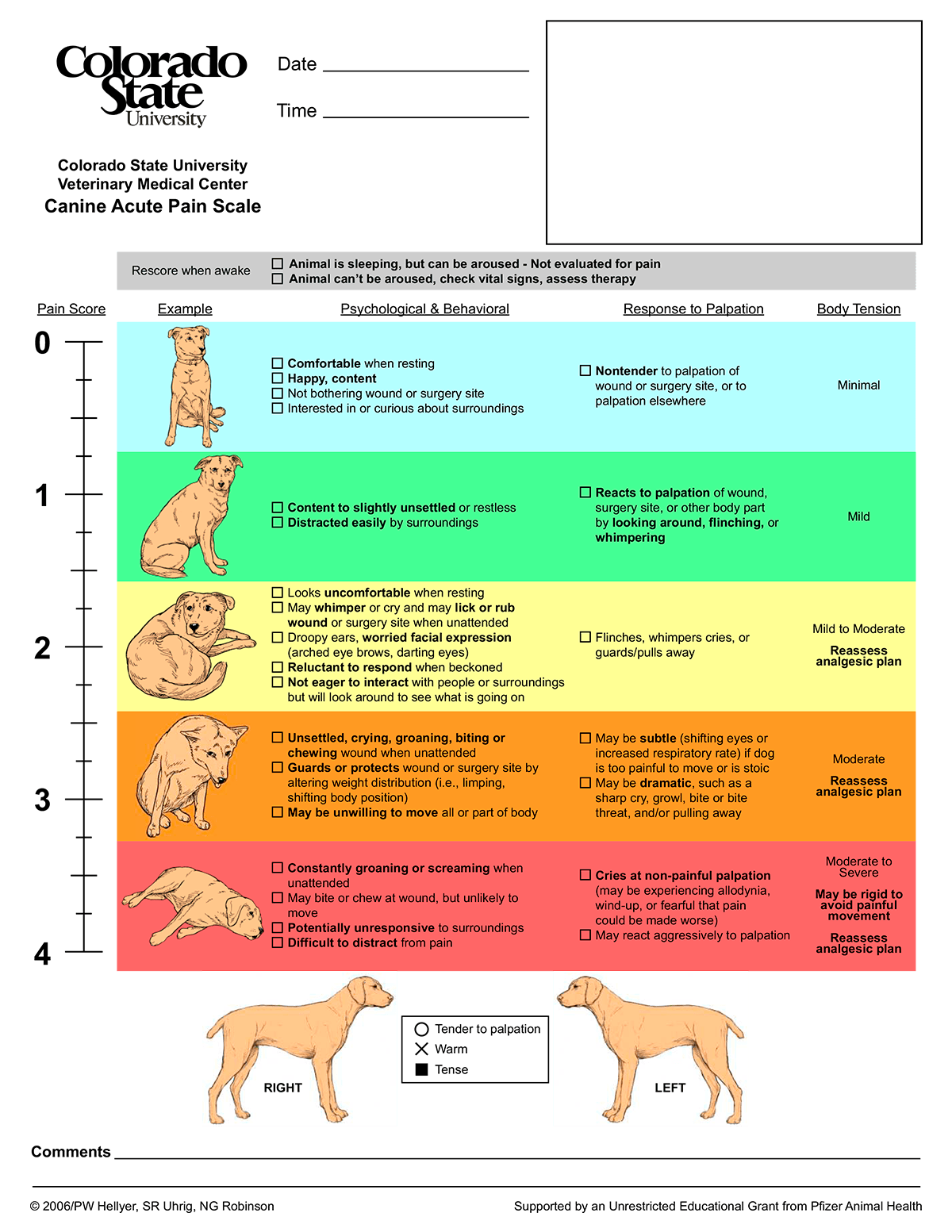

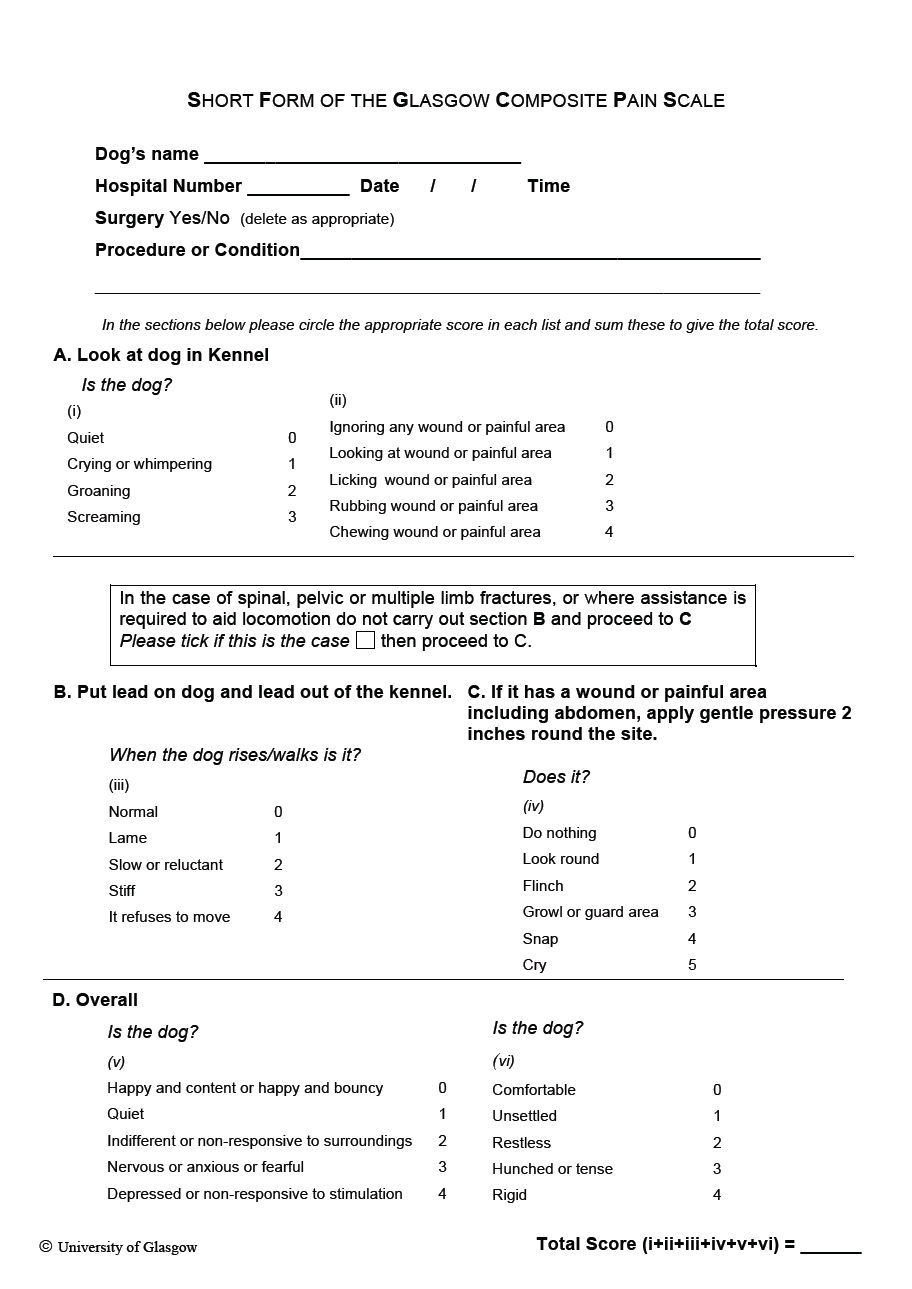

Within the veterinary community, two very common and adapted behaviour-based pain assessments are the Glasgow Composite Measure Pain Scale and the Colorado State University Acute Pain Scale.

Both systems have been validated in dogs (Reid et al, 2007). They have also proved reliable and sensitive to pain in dogs; however, the sensitivity of these in cats has long been debated.

Both of these pain scores are based on specific behaviours that, historically, have indicated pain in companion animals. The short-form versions of these forms are more commonly used in general practice and can be seen in Figures 5 and 6.

Although feline adaptations are available, their use has long been debated as they are not validated through research. The most validated pain scale through research in cats is the São Paulo State University-Botucatu Multidimensional Composite Pain Scale.

Coleman and Slingsby (2007) stated feline patients are less frequently pain scored than canine patients – and when they are, they receive a lower pain score.

It should be considered this may be due to the lack of an appropriate feline-specific pain scoring system at the time of the study, with a multidimensional scoring system validated following this (Brondani et al, 2013).

As aforementioned, this pain scoring system has been validated in cats is the São Paulo State University-Botucatu Multidimensional Composite Pain Scale (Table 1). Although this has been shown to be reliable and sensitive in cats, it can be time-consuming. It not only takes into consideration behaviours the patient shows, but the absence of certain behaviours, too. The patient also builds up a score by showing one or more behaviours – the more behaviours are shown in each category, the higher the patient will score.

| Table 1. The São Paulo State University-Botucatu Multidimensional Composite Pain Scale (extrapolated from Self [2009]) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item | Description | Score |

| Evaluate the cat’s posture in the cage for two minutes | ||

| 1 | Natural, relaxed and/or moves normally. | 0 |

| Natural, but tense; does not move, or moves little or is reluctant to move. | 1 | |

| Hunched position and/or dorsolateral recumbency. | 2 | |

| Frequently changes position or restless. | 3 | |

| 2 | • The cat contracts and extends its pelvic limbs and/or contracts its abdominal muscles (flank). • The cat’s eyes are partially closed (do not consider this item if present until one hour after the end of anaesthesia). • The cat licks and/or bites the surgical wound. • The cat moves its tail strongly. |

|

| All above behaviours are absent. | 0 | |

| Presence of one of the above behaviours. | 1 | |

| Presence of two of the above behaviours. | 2 | |

| Presence of three or all of the above behaviours. | 3 | |

| Evaluation of comfort, activity and attitude after the cage is open, and how attentive the cat is to the observer and/or surroundings | ||

| 3 | Comfortable and attentive. | 0 |

| Quiet and slightly attentive. | 1 | |

| Quiet and not attentive. The cat may face the back of the cage. | 2 | |

| Uncomfortable, restless and slightly attentive or not attentive. The cat may face the back of the cage. | 3 | |

| Evaluation of the cat’s reaction when touching, followed by pressuring around the painful site | ||

| 4 | Does not react. | 0 |

| Does not react when the painful site is touched, but does react when it is gently pressed. | 1 | |

| Reacts when the painful site is touched and when pressed. | 2 | |

| Does not allow touch or palpation. | 3 | |

| Total score | ||

| Analgesia should be given when total score is 4 or higher | ||

As mentioned, these types of pain scales can be time-consuming, as they stipulate the observer must watch the patient in a kennel for at least two minutes. After this, the observer must take the patient out of the kennel to assess its behaviour, and then evaluate the patient’s response to palpation of the painful area.

In total, this can take as long as five minutes for an experienced user, or longer if the user is unfamiliar with the system. In a busy hospital setting, this may not always be a viable way to assess pain.

In a study conducted by Coleman and Slingsby (2007), 96% of nurses in general practice felt their knowledge of pain scoring could be enhanced.

With such a large percentage of those asked stating their knowledge could be improved, this shows a significant gap exists in knowledge among nurses – not only relating to recognising pain behaviours, but also in the use of pain scoring systems to help distinguish pain.

It is important to remember, in both human and veterinary medicine, no “gold standard” way exists of assessing pain (Lascelles et al, 1999).

The author feels that to become more knowledgeable and comfortable assessing pain in animals, RVNs should be aware of common pain behaviours seen while also increasing the use of pain scoring in practice.