9 May 2023

Parasite prevention in the globetrotting pet

Ian Wright discusses the protection requirements for animals being taken abroad, as well as destination and lifestyle factors.

Image © thinglass / Adobe Stock

It is wonderful to be able to talk about the requirements of pet travel again. It shows some normality is returning to the world following the pandemic and people are getting back to thinking about taking their pets on holiday.

However, the world has changed, with the UK no longer being part of the EU and, as a result, more paperwork being involved with pet travel.

Quite rightly, people are concerned about getting this paperwork right. Owners face serious ramifications if animal health certificates are filled in incorrectly, with the potential of getting stuck at borders, being unable to travel with their pets or unable to get back into the UK.

But as well as animal health certificates, it is essential to discuss parasite control when people take their pets abroad.

The recent focus with pet parasites has been very much on dogs being imported into the country. A slightly different focus is required for pet travel, in that hopefully these cats and dogs are not infected with exotic parasites when leaving the UK. The aim is for them to stay that way, rather than the focus being on testing for pathogens they may already have.

Although it’s unlikely that any vet will have been filled with joy by the introduction of animal health certificates, they do mean owners have to be seen every time they travel abroad with their pets. This creates an opportunity to introduce the concept of parasite protection while pets are abroad. This can be different to parasite prevention, which is in place in a domestic setting.

An opportunity also exists in post‑travel clinics to discuss parasite prevention and give relevant treatments on their return, as well as refresh knowledge.

Some owners taking their pets abroad will be very familiar with the parasites involved, but many will be taking their pets abroad for the first time following the pandemic and will have no idea that they need additional parasite protection. It is, therefore, important to set aside time to sit with owners and discuss the parasites involved.

This can be beautifully nuanced, with pets potentially being exposed to dozens of different parasites, but four main parasite groups provide the most cause for concern.

Tapeworm

The tapeworm whose potential to enter the UK should be of greatest concern is Echinococcus multilocularis – a highly pathogenic, zoonotic tapeworm that we don’t want to establish in the UK. It has no health ramifications in dogs or cats if they become infected.

Risk of infection comes from pets finding a tasty, infected microtine vole or small rodent. Having eaten it, they become infected with the tapeworm. After 30 days, immediately infective microscopic eggs are passed in the faeces.

Foxes act as a natural reservoir of infection – and because European foxes have increased in numbers in recent years, the parasite has spread across most of Europe.

The UK is currently free of infection, but the concern is if infected animals enter the country and infect our own large populations of foxes and our rodents, it will be very difficult to eradicate. This is because it would take approximately 15 years from first human infection for clinical signs to appear.

Once the parasite is endemic in a country, an ongoing risk exists that humans will be exposed to eggs being passed in the faeces of dogs.

Alveolar cysticercosis – caused by E multilocularis – is a severe zoonotic condition, with cysts forming in the liver that can then metastasise in a similar way to a malignant tumour.

Fortunately, it is very simple to eliminate E multilocularis from dogs and cats – treatment with praziquantel every month will ensure eggs aren’t shed. If pets travelling abroad are treated every month, this will help to keep owners safe from exposure to infection.

It is still compulsory for dogs to have a praziquantel treatment one to five days before they come back into the UK, and this tapeworm treatment has been hugely important in keeping the UK free of E multilocularis.

It is essential for the UK and for other countries that are officially Echinococcus free – Ireland, Malta, Norway and Finland – that this compulsory treatment is kept in place.

Praziquantel, though, has a short half-life, so a one to five-day window exists where pets might get reinfected.

Cats are poor hosts for the parasites, with lower worm burdens with poorer fecundity, making this risk for them extremely low. However, for dogs entering the UK, the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) UK and Ireland recommends another praziquantel treatment within 30 days after they arrive back in the UK to minimise the risk of any eggs being shed.

This additional treatment is not just “a greater good” sell for UK biosecurity, but also for the individual owner’s safety.

Heartworm

The second major parasite of concern is Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm). It is potentially very pathogenic to dogs and, to a lesser extent, cats and ferrets. D immitis is a very large roundworm – around 10cm long – that lives in the heart chambers and pulmonary artery.

Dogs that are infected will eventually go into heart failure and are at risk of thromboembolism. Acute heart failure can also occur if the worms suddenly shift or die.

Cats tend to carry low or zero numbers of worms, but can also suffer from sudden death and acute complications from worm death. However, cats’ main issue with exposure to infection is the larvae migrating across the lungs, which can lead to respiratory signs.

Transmission occurs through infected mosquitoes, and licensed fly repellents for dogs are available. The flumethrin collar is not licensed for this purpose, but is likely to have some efficacy and can be used in cats.

Repellents will not be effective enough over time, though, to prevent some exposure – and this is why a monthly macrocyclic lactone is required when in endemic countries to prevent infection establishing.

Treatment should be used monthly while abroad and continue for at least one treatment after returning to the UK.

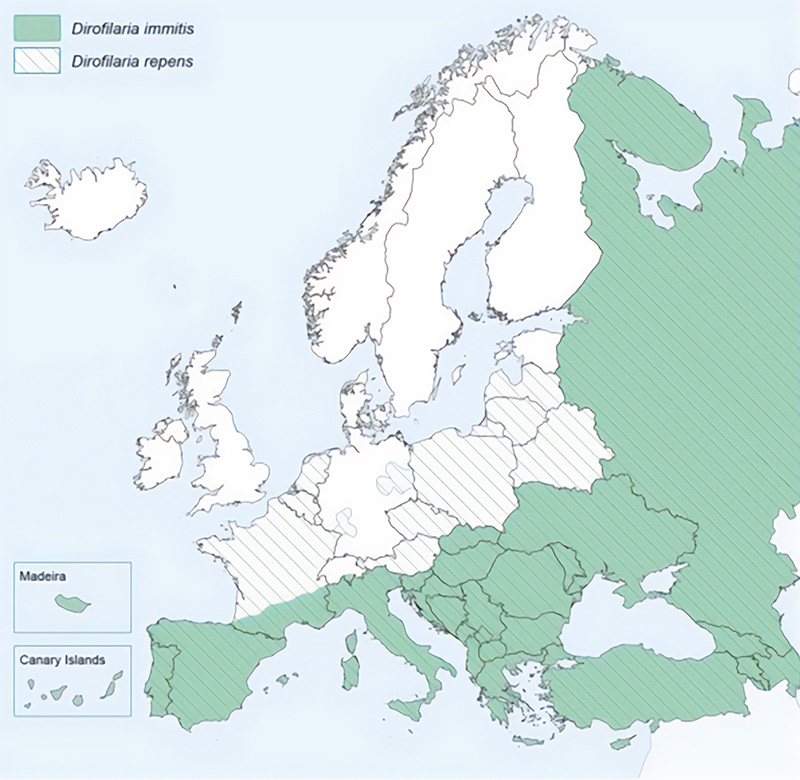

Mosquitoes capable of transmitting D immitis are present in the UK, but it is currently not warm enough for the parasite to complete its life cycle. However, climate change and increased movement of pets means heartworm is spreading quite quickly north and eastwards across Europe; it used to be traditionally a southern European parasite.

ESCCAP has a current distribution map (Figure 1), but the line marking the limit of its distribution is seasonally fluid and rapidly changing.

We need to bear this in mind when deciding whether dogs and cats that are traveling need heartworm prevention.

Leishmaniosis

Numerous species of Leishmania exist, but the one that infects dogs and cats primarily in Europe is Leishmania infantum. It is a significant zoonosis in countries that have the sandfly vector, but has very limited zoonotic potential in non-endemic areas. It is also a cause of severe immune-mediated disease in cats and dogs.

This parasite, a protozoan linked to trypanosomes, is limited mostly by the distribution of its sandfly vector. It can be transmitted reproductively by venereal and vertical routes, as well as via blood transfusion and possibly dog bites (Karkamo et al, 2014; Daval et al, 2016), but most infection, though, occurs via sandflies; therefore, sandfly repellency is the basis for prevention.

Although, as for mosquitoes, no product is 100% effective, repellency needs to be as effective as possible.

A number of pyrethroid spot-ons and a collar are licensed for sandfly repellency in dogs. It is likely the flumethrin collar has some efficacy and is the only safe product available to cats.

Repellent products should be applied a week before travel, to build up active prevention before travelling, and should be continued on return to the UK.

The advantage of using fly repellents is that they are also licensed to repel ticks – providing a way to limit the number of products owners need for their pets while abroad.

It is very important to read the data sheet carefully. Swimming and shampooing can affect how long these products last.

Other methods exist for helping prevent sandfly exposure, but they are not a substitute for using a repellent.

Sandflies are poor fliers, so anyone camping should pick a fairly breezy, exposed area. But even sleeping upstairs can make a difference, because sandflies have trouble flying to any reasonable altitude.

Fine mesh, insecticide‑impregnated bed nets are an option, but should not be used with cats because of the pyrethroid risk. Care needs to be taken with dose and contact, but they can be useful – especially for humans.

Leishmania’s distribution is similar to that of heartworm, with southern Europe endemic and seasonal fluctuations through France and eastern Europe. Pets travelling to these areas should have protection in place.

For anyone travelling with their dog for a long period to a Leishmania-endemic country, or visiting one frequently, vaccines are available that limit disease. One has just been launched in Europe that also limits infection, but is not, at the time of writing, available in the UK.

Ticks

Exposure to ticks while abroad can be high. Ticks of concern include:

- Ixodes, which is present across Europe and capable of transmitting tick-borne encephalitis virus, which is only present in patches in the UK.

- Dermacentor reticulatus, which is present across most of Europe – particularly central, northern and eastern Europe – and can transmit Babesia canis.

- Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Figure 2), which is a veracious feeder and can complete its life cycle very quickly. Its larvae nymphs and hosts all feeding on a wide range of hosts. This is present in southern and eastern Europe. Although it doesn’t like our outdoor climates, it can survive and infest in centrally heated homes (Hansford et al, 2017). As well as transmitting a range of pathogens that can affect dogs and, to a lesser extent, cats, they also transmit rickettsial disease, including Mediterranean spotted fever, which is a threat to humans.

It is important to minimise tick exposure as much as possible – and the approach is twofold:

- Preventive products should be used.

- Pets should be regularly examined for ticks.

Preventive products should either kill rapidly or kill and repel, such as an isoxazoline or a pyrethroid.

For owners travelling to a Leishmania‑endemic country, it makes sense to use a repellent product to help prevent exposure to both. However, tick prevention is not 100% effective, so in addition to using these products, checking pets’ coats after outdoor activity and removing any found with a tick removal device is very important; owners should also check themselves.

When returning to the UK, pets should be checked again and tick-preventive coverage should be continued to ensure any surviving ticks are killed.

Because single tick products are not 100% effective, isoxazolines and pyrethroids can be used in combination where risk is considered to be particularly high or where clients want that extra level of protection.

Opportunities to discuss prevention when abroad

Prevention abroad can be tricky because it involves mostly prescription products. Therefore, the best time to discuss owners’ parasite prevention needs while abroad is while completing the animal health certificate.

However, time is also a factor when completing certificates, so a website page that covers all of this is very useful. It is great to see a lot of practice websites have a pet travel section that runs through the preventive options – at least in summary – to help owners prepare.

In addition, waiting room posters and leaflets explaining the four main parasites can trigger discussion. These can be designed in practice; ready-prepared materials are also available.

The key, though, in terms of compliance is making prevention as simple as possible. Tick‑box arrangements are a good way to engage clients and try to make it less overwhelming. Clients ultimately want to enjoy their trip abroad rather than worry about the parasites their pets may face.

Conclusion

While this may seem a daunting number of parasites to cover with owners, these can be simplified by combining protection.

Leishmania protection can be combined with ticks; tapeworm prevention can often be combined with macrocyclic lactones in a variety of options.

For short trips, if minimal tapeworm protection is required some spot-ons will protect against heartworm alongside tick/repellent products.

A very limited number of products can, therefore, protect against these groups and keep pets relatively safe.