21 Jan 2020

Robert E Matus discusses presentation, diagnosis and treatment of this lymph node disease.

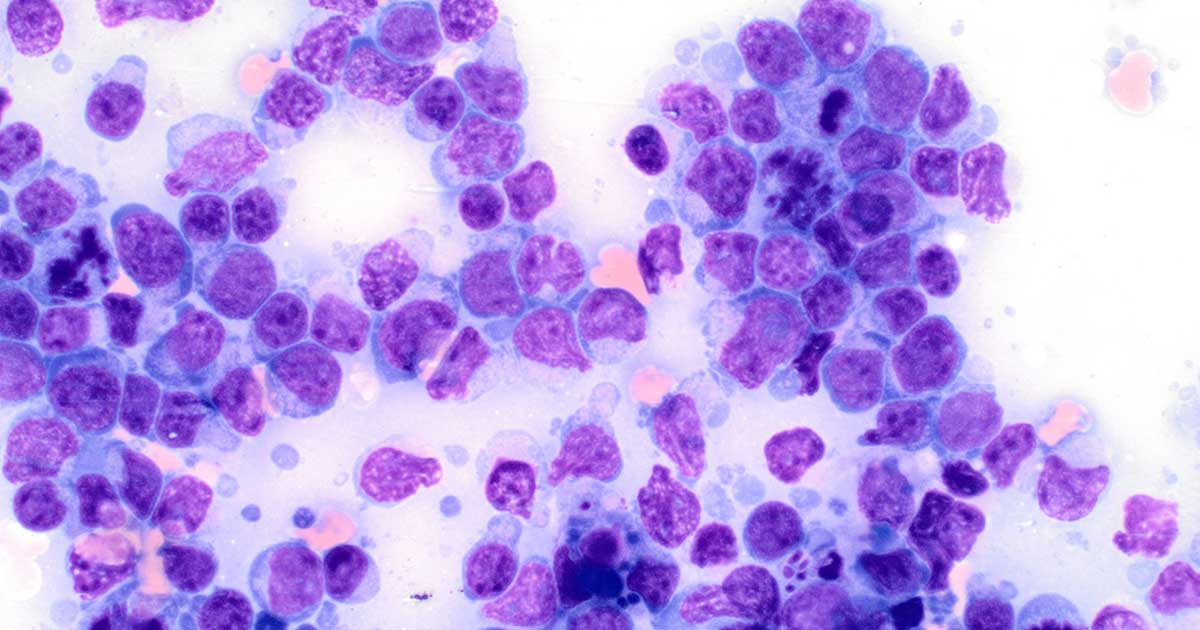

Figure 1. Large cell high grade lymphoma (50× oil immersion).

Lymphoma in the dog is the most common haematopoietic malignancy we expect to deal with in veterinary practice.

Estimated to occur in 24 out of 100,000 dogs annually in the general population at risk, golden retrievers, German shepherd dogs, collies, standard poodles, Old English sheepdogs and Scottish terriers are over-represented.

With clinical application and availability of diagnostics developed over the past 30 years, we can fairly well predict biological behaviour in most instances and recommend appropriate treatment. Lymphoma is quite responsive to chemotherapy, and good quality of life may often be achieved for a year or more. Unfortunately, in the majority of cases we will not provide a cure, and long-term response may be seen in only 20% of dogs treated.

The most common presentation in the dog is generalised lymphadenopathy developing over a few short weeks. The patient may be unaffected or have non-specific illness. Regardless, the time to progression without treatment is usually only an additional three weeks.

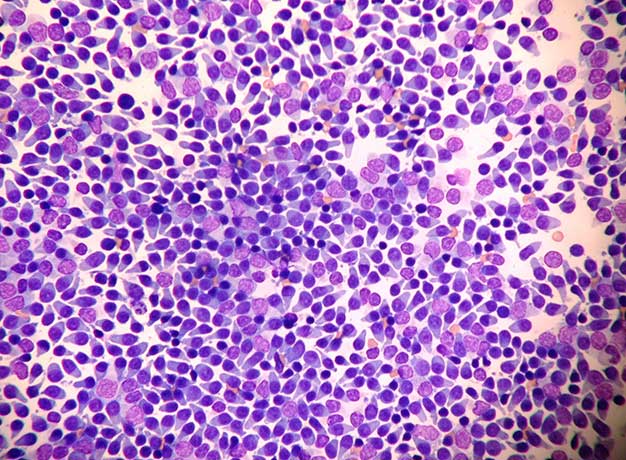

Diagnosis may be achieved rapidly by performing fine needle aspiration of a lymph node and submitting for cytology. Cytology may suggest grade and phenotype (Figures 1 and 2); however, follow-up testing for determination of T-cell or B-cell origin is certainly indicated.

Immunophenotyping may be performed by immunocytochemistry, immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry (Thalheim et al, 2013). Flow cytometry may be performed on lymph node and bone marrow aspiration biopsy samples. This test involves passing a single cell suspension through a gated laser light source to establish diagnosis by size, physical characteristics and immunofluorescence, with monoclonal antibodies used to identify cell surface protein groups associated with cellular differentiation and phenotype.

In those patients with evidence of leukaemia, flow cytometry of peripheral blood samples may be recommended to help determine diagnosis.

A majority of dogs will have a high grade B-cell phenotype lymphoma. Prognosis for response and survival for these patients is considered better than for those dogs with high grade T-cell phenotype lymphoma (Valli et al, 2013).

Clonality – the determination of single cell line proliferation of either T-cells or B-cells, as seen in lymphoma versus lymphoid hyperplasia with multiple cell line proliferation – may be established by PCR for antigen receptor rearrangement (PARR). Determination of phenotype by PARR is also possible, but may sometimes be inconclusive as genetic changes may affect both B-cell and T-cell antigen receptors (Thalheim et al, 2013).

Tissue biopsy and histopathology may be necessary to establish the diagnosis of lymphoma from atypical lymphoid hyperplasia and classify lower grade versus the more common higher grade lymphoma.

A minimally invasive Tru-Cut needle biopsy procedure may allow for diagnosis by histopathology and determination of phenotype by established immunohistochemistry. However, the ideal biopsy is whole lymph node excision as architecture and cell populations may be evaluated. The decision to obtain a tissue biopsy may be affected by patient risk and owner concerns on the need for sedation/anaesthesia with surgery itself.

Blood tests for acute phase proteins are now available that may provide information in the diagnosis and management of lymphoma. C-reactive protein and haptoglobin are produced by the liver in response to inflammation and high levels are known to occur in dogs with lymphoma. Thymidine kinase levels associated with cellular proliferation may also be elevated in these dogs.

Although not diagnostic for lymphoma in and of themselves, they may be of value in combination with cytopathology in establishing diagnosis and relapse in follow-up of treatment response. What we do not know, however, is whether early recognition of possible lymphoma and relapse identified only by the presence of elevation in these markers will allow us to routinely recommend initiation of treatment at that time. If this testing is to be used in follow-up response to treatment and relapse, it is best to have a pretreatment baseline level performed (Bryan, 2016).

In establishing clinical stage of disease in lymphoma, a general consensus exists that dogs with stage I and II disease (the presence of single or only regional nodal involvement) may have a more prolonged remission compared to dogs with the more commonly presenting stage III (generalised lymphadenopathy) disease, but controversy exists on whether more advanced disease stage IV (liver and spleen involvement) is truly predictive.

This may be due to past studies using only radiography for determination of stage versus ultrasound imaging and fine needle aspiration, which may be more commonly performed today. Stage V lymphoma (peripheral blood and bone marrow involvement) must be differentiated from aggressive acute lymphoblastic lymphoid leukaemia or the more indolent lower grade chronic lymphocytic leukaemia – all of which carry a different prognosis (Flory et al, 2007).

In general, treatment may be considered with a minimal database of routine laboratory testing (complete blood count, biochemistry profile) and lymph node cytology – ideally with either immunophenotyping or PARR performed.

Imaging studies do give more information, but it is difficult to, again, determine their true role in determining treatment recommendations. Prognosis for the otherwise healthy dog with generalised stage III to V higher grade lymphoma is similar overall based on many published studies.

The prognosis may be better in dogs with stage I and II disease. However, notable observed changes in physical status – such as major organomegaly on exam, marked lymphocytosis, anaemia and hypercalcaemia on laboratory studies – may affect prognosis overall.

A major prognostic indicator of stage of disease is whether the dog is showing signs of clinical illness (substage B) or not (substage A). In all studies to date, physical condition as a substage significantly affects response and survival. In the severely compromised patient, we will attempt to stabilise with appropriate supportive care – either as an outpatient or in hospital prior to administration of induction chemotherapy.

Treatment for dogs with lymphoma is generally chemotherapy, for which several protocols have been established and are recommended based on the individual patient characteristics. We have evolved from the basic cyclophosphamide, Oncovin (vincristine) and prednisone or prednisolone (COP); or cyclophosphamide, Oncovin (vincristine), cytosine arabinoside and prednisone or prednisolone (COAP) to COP plus doxorubicin (hydroxydaunorubicin; CHOP) as standard protocols for dogs with high grade lymphoma (Hosoya et al, 2007). However, it is reasonable to consider an alkylating agent-based protocol or including additional alkylating agents – such as lomustine and/or chlorambucil – in a CHOP protocol in dogs with higher grade T-cell lymphoma.

The alkylating agent-based protocols are more intensive and most commonly used to treat relapse of lymphoma in combination with L-asparaginase (Kitchell and Ho, 2011). It is still unclear whether they are truly more effective than using CHOP-based protocols for initial chemotherapy overall.

A new conditionally approved chemotherapy drug – rabacfosadine – is being used by veterinary oncologists in the US, although it is not available in the UK. This drug is a dual pro analogue for guanine synthesis, which inhibits DNA replication and preferentially accumulates in canine lymphoid cells. Rabacfosadine has demonstrated clinically effective response as a single agent, and in combination with doxorubicin in dogs with both naive and relapsed lymphoma (Thamm et al, 2017).

We have modified the length of treatment protocols and largely abandoned maintenance phase treatment altogether in dogs presenting with higher grade B-cell lymphoma. Most recently, the use of a short 15-week CHOP-type protocol has shown equivalent results to the standard 6-month length of treatment (Curran and Thamm, 2016). Repeated treatment at time of relapse may be of equal value to the more prolonged protocols in dogs with higher grade lymphoma.

Treatment of lower grade lymphoma of either B-cell or T-cell phenotype is usually less intensive, and response may be achieved with single agent chlorambucil and prednisone. In some cases of “indolent” B-cell or low grade T-cell lymphoma, we may not initiate treatment until progression of disease is observed, which may be many months to occurrence.

Other more novel approaches to treatment have been available in the US for the past few years, with conditional Food and Drug Administration approval of monoclonal antibodies for B-cell and T-cell lymphoma. However, they failed to demonstrate overall significant clinical improvement and have been withdrawn by the manufacturers.

A commercial lymphoma DNA vaccine is available with conditional approval, but, again, is of questionable value in improving treatment outcome. Only now are anecdotal reports from clinical oncologists forthcoming.

Following the diagnosis of lymphoma, a primary concern is to provide help to the owner in deciding whether to proceed with investigation or consider referral for further evaluation and treatment.

As lymphoma is not curable, questions are most often related to benefit versus duress, practicality and costs of doing so. General surveys to assess these questions are of limited availability, but most owners of dogs with lymphoma are appreciative of the attempt to provide good life for a period of time.

Diagnostic and treatment plans may be modified to accommodate individual circumstances without sacrificing professional integrity or the best interests of the patient and owner. Alternative treatment protocols may be offered for the owner to consider in this regard. Our goals are to provide for professional expertise to establish diagnosis, prognosis and treatment in the individual patient.