11 Nov 2025

Mike Davies BVetMed, CertVR, CertSAO, FRCVS emphasises the importance of identifying and managing inappetence in cats and dogs.

Image: anastas_ / Adobe Stock

Animals have to eat daily to meet their energy and essential nutrient requirements. Sometimes, they lose their appetite and either eat an insufficient amount (hyporexia) or stop eating altogether (anorexia).

In both cases, steps should be taken to ensure adequate food intake, otherwise metabolic pathways become catabolic, impairing normal metabolism, and the animal uses stored resources to meet metabolic needs for energy. Reserves of stored essential nutrients are also depleted.

These changes result in undesirable changes, including tissue breakdown, reduced activity, reduced resistance to infections and impaired healing and recovery.

Inappetence is a serious clinical sign and attempts should be made to identify the underlying cause, which may be:

After a short period of starvation (about 72 hours), degradation of glycogen is increased and then lipolysis is stimulated. After utilisation of stored glycogen, the glycaemia needed for function of the brain and erythrocytes is maintained by gluconeogenesis.

By day three of starvation, the metabolic rate will have dropped to conserve resource. Decreased blood glucose causes reduced serum insulin and reduced conversion of T4 to T3. T3 levels decline after just 24 hours, and they are 40% to 50% lower than in fed animals by day three.

By day five of anorexia, animals are using endogenous resources for metabolism – fatty acids and ketones – and low insulin stimulates lipolysis. Although amino acids are conserved, branch-chain amino acids in muscle are catabolised.

In addition, inappetence results in specific nutrient deficiencies and key issues if malnutrition is present, including:

Rational decision-making to ensure adequate alimentation requires a full history and physical examination – including a nutritional assessment.

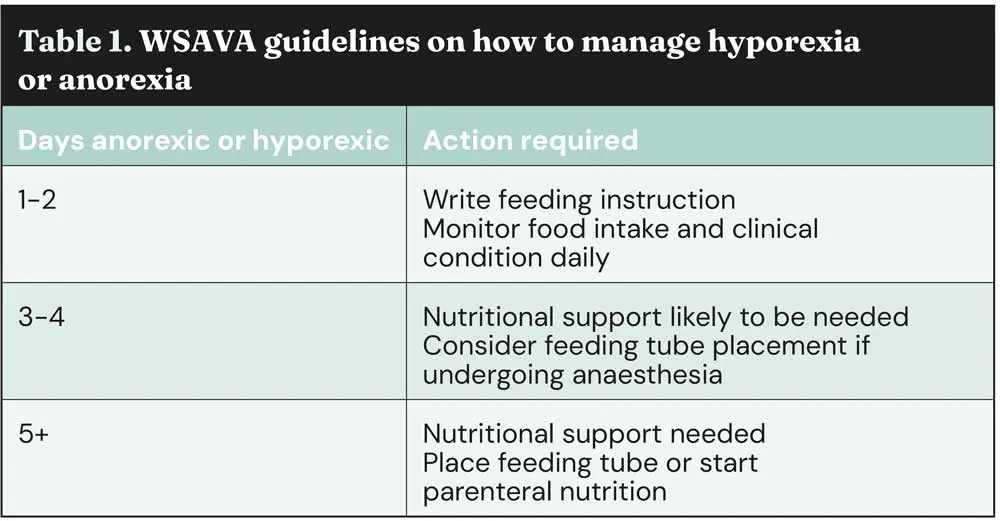

The guidelines in Table 1 on when to implement tube feeding are, in my opinion, delayed for too long, as we know serious and negative metabolic changes are occurring by day three of starvation.

Review the animal’s normal ration, including treats, snacks and supplements. Assess body condition score; optimum is 4/9 to 5/9. Aim to ensure usual nutritional intake to maintain optimum bodyweight/body condition score and employ assisted feeding if necessary. Objectives are to:

You will need to decide:

There is no single food that will meet all animals’ specific needs, and the food selected must be based on an individual’s unique requirements.

If anorexia has been present for seven days or longer, it is advisable to feed a high-fat food for energy, unless the animal has fat metabolic issues (for example, pancreatitis or hypertriglyceridaemia).

If anorexia has been present for less than seven days, a regular food can be used with a mixture of carbohydrate/fat/protein for energy.

Tubes smaller than French gauge 8 (8 Fr) are suitable for the administration of liquid foods. Larger-sized tubes are suitable for blended foods.

For tube feeding, calculate the animal’s approximate energy requirement to meet and avoid overfeeding, as this causes metabolic and mechanical complications. Formulae to calculate RER energy requirements can be used:

30(BWkg) + 70

70(BWkg)0.75

97(BWkg)0.655

Guidelines are also provided by several companies and on the WSAVA website (www.wsava.org)

Feeding warmed food to meet the animal’s RER for the first 24 hours is recommended. The feeding rate needs to be slow: 5ml of food per minute. Aim to feed the daily amount in several small meals.

Gastric capacity is just 5ml/kg to 10ml/kg bodyweight when food is reintroduced after a period of anorexia, and if you feed too fast the animal will start gulping, salivating, retching or vomiting. If these signs occur then stop, reduce meal size by 50% and gradually increase again.

After a period of starvation, a patient could develop “refeeding syndrome”, which results in dramatic changes in phosphate, magnesium and potassium, and can result in potentially fatal pulmonary, cardiovascular, neurologic and neuromuscular abnormalities. So, after a period of anorexia, start feeding at 25% of RER and increase gradually over a four to five-day period.

Tubes must be flushed with water after every feeding session. End-port tubes are easier to manage, as blind-ended tubes accumulate food debris.

Stoma care is very important. Clean with antiseptic after every feed, monitor for signs of pain or inflammation, which necessitate prompt removal, and consider prudent use of antibiotics if necessary. Bandages should be checked daily and kept clean.

Elemental or monomeric foods contain:

These foods are usually delivered direct into the jejunum and do not require digestive enzymes to be present in the lumen of the intestine. They are suitable for all tubes, including J-tubes.

Human monomeric diet products are suitable for dogs (except those with protein-losing diseases), but they are too low in protein for cats, and provide insufficient amounts of other essential nutrients (such as arachidonic acid, arginine and taurine) for long-term feeding of cats.

Polymeric foods contain:

The ingredients in these foods require normal GI function to be digested and absorbed. These diets can be diluted with water to facilitate tube feeding and some become more liquid when stirred.

Some veterinary diets claim to meet all Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) guidelines, but check with your suppliers.

These polymeric liquid diets have low energy density (1kcal/ml to 1.25kcal/ml).

Liquid milk replacers are inappropriate because they have high osmolarity (more than 300mOsm/l) and low energy density (less than 1kcal/ml).

Complete foods can be administered in accordance with AAFCO/FEDIAF guidelines, and can be formulated to meet special needs in disease situations.

I believe therapeutic foods are the ideal solution because they provide a correct balance of nutrients to energy density, with modifications specific to the disease an animal has.

Wet foods (water content usually more than 80%) are easier to administer, but water can be added to dry foods to achieve moist consistency.

Foods with small particle size facilitates administration through a tube.

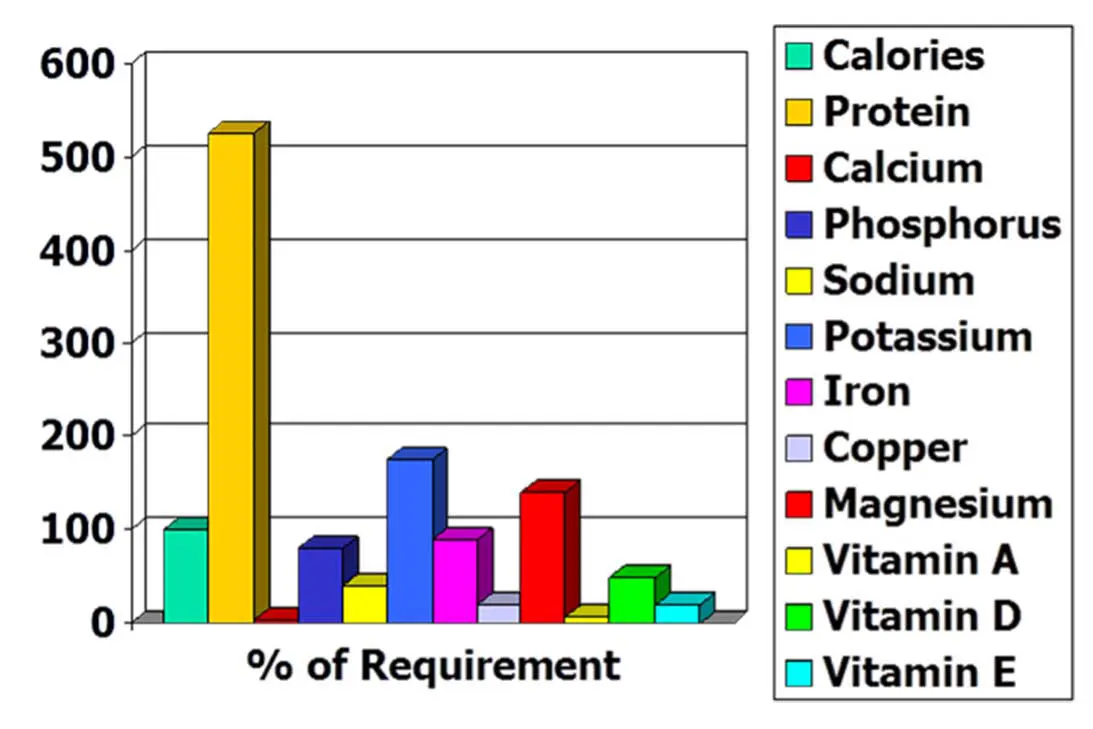

Does your practice still use “bland diets” (for example, chicken and rice) during the postoperative period? I was taught to feed a chicken and rice diet, but this is totally inadequate at supporting postoperative recovery and wound healing, as illustrated by Figure 1.

Boiled rice consists almost entirely (96%) of water and carbohydrate, and is deficient in many essential nutrients.

Whenever possible, voluntary intake of food should be encouraged. If this is not feasible, use assisted feeding. Whenever possible use oral route first – “if the gut works, use it”.

If the GI tract is non-functional due to obstruction, intractable vomiting, acute pancreatitis or post-trauma, consider parenteral nutrition; for the short term, this can be by peripheral parenteral nutrition, but for the long term, a central line is needed for parenteral nutrition.

Many owners believe their pet is a fussy eater, but the evidence is that after three days in a kennel, a dog or cat will eat anything it is given, unless it is seriously ill.

Steps that can be taken to encourage food intake include:

I do not like to use appetite stimulants, as they do not address the underlying problem, voluntary feeding rarely continues after they have worn off, RER is rarely met and most have undesirable side effects.

Hand feeding – especially from the right owner – can be very effective, but it can be difficult to achieve RER .

Force feeding is manually forcing food to the back of the mouth. Aspiration is a risk, so this is not advised.

Bottle feeding is used especially for milk replacer administration to neonates.

With syringe feeding, for neonates, fill the syringe with milk replacer; for adults, cut off the end of the syringe and fill by inserting into a can or pouch of wet food. No general anaesthetic is needed. Aspiration is a risk, so administer beyond the base of the tongue slowly.

Wide-bore orogastric tubes are routinely used to deflate gastric bloat and they are well tolerated by most dogs. They can be used for daily administration of the animals nutritional requirements. No general anaesthetic is needed.

The tubes can be a red rubber or polyvinyl tube (8Fr to 24 Fr), and they can be passed direct into the stomach.

Naso-oesophageal/gastric feeding tubes are usually placed for three to seven days. If they are needed for longer, it is recommended to move from one side to the other every week.

Several different types of tube are available, including polyurethane tubes (6 Fr to 8 Fr; 90cm to 100 cm) with and without tungsten-weighted tips, or silicone tubes (3.5 Fr to 10 Fr; 20cm to 105cm). The 8 Fr tubes are suitable for most dogs; 5 Fr for cats.

The tubes can be placed into the caudal oesophagus or the stomach. Contrary to advice given to the veterinary profession in previous decades, in human medicine these tubes are still routinely placed into the stomach with aspiration of gastric acid – the gold standard to confirm placement, not imaging. In a UK study in dogs (Camacho and Humm, 2024) no significant difference was seen in new onset regurgitation/vomiting rate, or complications while the tube was in situ between the naso-oesophageal and nasogastric groups. So, it probably does not matter whether the distal end of the tube is placed into the stomach or oesophagus.

The length of tube needed is measured from nasal planum to caudal edge of the last rib. The tube is lubricated and passed ventrally and medially through the ventral meatus. Sometimes, the top of the nasal planum has to be pushed up dorsally to facilitate entry into the ventral meatus – so-called pug-nose appearance.

It is important to check that the tube is in the oesophagus/stomach and not in the trachea; for example, by aspirating acidic material from the stomach, or failing to stimulate a cough reflex by injecting a very small volume of saline through the tube.

An advantage of nasogastric or naso-oesophageal tubes is that a general anaesthetic is not needed. They are also easy to remove.

These tubes may not be appropriate if the animal has nasal, oral or pharyngeal disease or trauma. The tubes can be regurgitated back up the oesophagus and, sometimes, they are irritant and removed by the animal.

Complications include epistaxis, accidental or deliberate removal of tube (50%, even with a collar in place), so protect with an Elizabethan collar.

These tubes are not advised if the animal is vomiting or has respiratory disease.

Under general anaesthesia, pharyngostomy tubes used to be placed through the pharynx wall cranial to the hyoid bone, exteriorised on the left side of the neck and, from the mouth, passed down into the oesophagus/stomach, but they proved quite irritant for the animal and are no longer routinely used.

Under general anaesthesia, long curved forceps are passed down the oesophagus, with the curved point pushed out on to the left side of the neck caudal to the hyoid bone. A cut down stab incision is made over the tip of the forceps, which are used to grab the distal end of the tube.

This is withdrawn back into the mouth, then pushed caudally down to the distal oesophagus or into the stomach.

These tubes are large (12 Fr to 19 Fr, usually), and a large volume of food can easily be passed down these tubes to meet daily requirements.

Oesophageal tubes are well tolerated and can be left in situ for weeks to months. They are easily removed.

Gastrostomy tubes allow bypass of the oral cavity and oesophagus .

Gastrostomy tubes are wide-bore mushroom-tipped tubes (16 Fr to 28 Fr), which allow a large amount of food to be administered easily, direct into the stomach lumen. They can be placed intraoperatively, blind using a placement device or as a percutaneous (endoscopic) gastrostomy (PEG) tube. Like all stomas, care is needed to monitor for inflammation or infection at the tube site, but these tubes are very well tolerated and can be left in situ for long-term feeding (weeks, months or even years).

Some dogs vomit with bolus feeding; if so, use a slow-rate feeding pump or gravity feeding as required.

Potential complications of gastrostomy include:

Jejunal (jejunostomy) tubes (or J-tubes) bypass the upper GI tract and are ideal for patients with acute pancreatitis or those that have undergone major upper alimentary tract surgery or have serious pancreatic or hepatic disease. As the foods administered through J-tubes are monomeric, it avoids the need for contact with digestive enzymes and bile salts. These fine bore tubes (5 Fr to 8 Fr) can be inserted at laparotomy across the abdominal wall direct into the jejunal lumen, or very long J-tubes can be passed through an oesophagostomy or gastrostomy tube and pushed through the pylorus using an endoscope. Naso-jejunal tubes are also used in human medicine. Patients with J-tubes can be fed by bolus, but it is usual to feed by slow continuous administration using a pump. The recommendation is to set the feeding rate so as to administer the RER slowly over a 24-hour period.

Complications can include local infection at the surgical site or peritonitis and, rarely, in the case of long tubes passed through the stomach, the tube can return to the stomach by reverse peristalsis.

When food cannot be administered by any other route, IV administration is possible for a short period of time. This can be partial parenteral nutrition aimed at giving some essential nutrients and energy, but not the daily requirement, or total parenteral nutrition aimed at meeting all daily requirements for energy and essential nutrients.

Aseptic precautions are essential when placing the cannulas, and separate IV lines are needed to administer the fluids, electrolytes, fats and other nutrients.

Despite careful precautions the IV line usually fails in 48 hours due to inflammation and infection around the cannula. These have to be removed immediately when there are signs of inflammation to avoid the serious complication of sepsis.