15 Nov 2019

Renal disease in geriatric patients

Simon Tappin reviews the treatment options for this issue in dogs and cats, as well as the challenges they present.

Image © christels / Pixabay

Older animals often present with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Sometimes this is symptomatic; often this has been found as part of evaluation of other clinical problems – offering both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in these patients.

Lots of options are available for treatment for both cats and dogs, with various levels of evidence for their effectiveness.

Making treatment decisions can, therefore, be difficult – firstly, from the point of view of having evidence to make interventions, but also the owner and patient factors, such as treatment/diet compliance, costs and follow-up visits for monitoring.

The goals of treatment of both dogs and cats with CKD are to:

- reduce the clinical signs associated with azotaemia

- minimise electrolyte, vitamin and mineral loss

- support adequate daily nutrition

- modify the progression of renal disease

So, what can you do?

Understanding the disease

Firstly, before jumping into treatment, it’s important to take a step back and assess the stage of the renal disease present. This allows both appropriate monitoring and ongoing treatment, but is also a good starting point to start a discussion of the associated prognosis and expected responses to treatment.

The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) guidelines are well recognised on the basis of staging renal disease from 1 to 4 (Table 1). Animals are scored initially on fasting blood creatinine concentration, which is assessed on at least two occasions when the patient is stable.

| Table 1. Staging of chronic kidney disease based on blood creatinine concentration (adapted from IRIS, 2017) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Blood creatinine (μmol/l) | Comments | |

| Dogs | Cats | ||

| At risk | <125 | <140 | History suggests the animal is at increased risk of developing CKD in the future because of a number of factors (such as exposure to nephrotoxic drugs, breed, high prevalence of infectious disease in the area, or old age). |

| 1 | <125 | <140 | Non-azotaemic. Some other renal abnormality present (such as inadequate urinary concentrating ability without identifiable non-renal cause, abnormal renal palpation or renal imaging findings, proteinuria of renal origin, abnormal renal biopsy results, increasing blood creatinine concentrations in samples collected serially). |

| 2 | 125 to 180 | 140 to 250 | Mild renal azotaemia (lower end of the range lies within reference ranges for many laboratories, but the insensitivity of creatinine concentration as a screening test means animals with creatinine values close to the upper reference limit often have excretory failure). Clinical signs usually mild or absent. |

| 3 | 181 to 440 | 251 to 440 | Moderate renal azotaemia. Many extrarenal signs may be present, but their extent and severity may vary. If signs are absent, the case could be considered as early stage 3, while presence of many or marked systemic signs may justify classification as late stage 3. |

| 4 | >440 | >440 | Increasing risk of systemic clinical signs and uraemic crises. |

Animals are then substaged, based on proteinuria and blood pressure (Tables 2 and 3).

| Table 2. Substaging by proteinuria (adapted from IRIS, 2017) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Urine protein:creatinine ratio | Substage | |

| Dogs | Cats | |

| <0.2 | <0.2 | Non-proteinuric |

| 0.2 to 0.5 | 0.2 to 0.4 | Borderline proteinuric |

| >0.5 | >0.4 | Proteinuric |

| The urine protein:creatinine ratio should be measured in all cases, provided no evidence exists of urinary tract inflammation or haemorrhage, and documenting normal plasma protein levels. Ideally, staging should be done using at least two urine samples collected over about two weeks. Patients that are persistently borderline proteinuric should be re-evaluated within two months and reclassified as appropriate. | ||

| Table 3. Substaging by blood pressure (adapted from IRIS, 2017) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Blood pressure substage | Risk of future target organ damage |

| <140 | Normotensive | Minimal |

| 140 to 159 | Prehypertensive | Low |

| 160 to 179 | Hypertensive | Moderate |

| >180 | Severely hypertensive | High |

| Patients should be acclimatised to the measurement conditions and multiple measurements taken. The final classification should rely on multiple systolic blood pressure determinations, preferably done during repeated patient visits to the clinic on separate days, but acceptable if during the same visit with at least two hours separating determinations. Patients are substaged by systolic blood pressure according to the degree of risk of target organ damage, and whether evidence exists of target organ damage or complications. Some breeds, particularly sight hounds, tend to have higher blood pressure than other breeds, and breed-specific reference ranges should be used where possible. | ||

In animals with low body condition scores, creatinine measurement alone may underestimate their IRIS score.

A lot of interest and discussion has arisen into the use of symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) as a biomarker. IRIS guidelines suggest a step up in treatment recommendations in patients with raised SDMA – for example, an IRIS CKD stage 2 patient with a low body condition score and SDMA greater than 25µg/dl may suggest an overestimation in renal function and treatment recommendations as per stage 3 patients.

Similarly, an IRIS CKD stage 3 patient in low body condition with an SDMA greater than 45µg/dl should potentially receive treatment as per stage 4 patients.

Understanding SDMA as a biomarker is increasing all the time – and these guidelines are likely to change subtly over time as a result of our growing experience.

What changes can we make?

Depending on the IRIS stage and substages, various treatment recommendations can be made. Variable evidence exists for most of these recommendations – and it’s important to balance what would be considered gold standard treatment against the owner’s finances and practicalities, as well as patient compliance.

Diet

Dietary modification is the mainstay of management of CKD in both cats and dogs, and has been for several decades. Over that period, renal diets have become much more palatable and, therefore, better accepted by patients, especially cats.

However, it’s important to note dietary effects are exerted over the long term – and for acutely unwell patients, maintaining a good calorie intake with a familiar food, with a gradual change to the new renal diet in the home environment, can be more successful (Figure 1).

The main concepts for dietary manipulation in CKD are to limit phosphate intake (which reduces secondary renal hyperparathyroidism and helps delay the progression of renal disease), increase omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (thought to help prevent progression of CKD through lowering cholesterol, reducing inflammation and antioxidant effects), and limit dietary protein (although contested, lowering protein content is thought to reduce the clinical signs of azotaemia).

In more advanced disease, managing appetite itself can be an issue – and therapy such as supplemental cobalamin, maropitant and mirtazapine may have a beneficial effect.

Managing phosphate

Retention of phosphorus through CKD leads to hyperphosphataemia and secondary renal hyperparathyroidism.

Guidelines suggest aiming to control plasma phosphate to lower than 1.6mmol/L, with monitoring every three to four weeks until stable and every three months thereafter.

Dietary management is usually the first step in controlling phosphate levels – but if this is not successful, or if a diet is not tolerated, intestinal bonding agents, such as aluminium hydroxide or calcium acetate, have been suggested. Doses vary, depending on IRIS stage and the amount of phosphate being fed.

Care should be taken to monitor for signs of aluminium toxicity (muscle weakness and microcytosis) and hypercalcaemia with calcium-containing treatments.

Potassium

Hypokalaemia and depletion of total body potassium are relatively common in cats with stages 2 and 3 CKD, but less so in dogs and cats with stage 4 disease.

Supplemental potassium may be required IV in symptomatic patients; however, if the patient is well then increasing oral intake (1mmol/kg/day to 2mmol/kg/day) is suggested by adding potassium gluconate or potassium citrate.

Metabolic acidosis

Many patients with CKD will be acidotic due to the reduced ability to excrete hydrogen ions, leading to metabolic acidosis.

Correction of the acidosis may help to reduce signs of uraemia, limit skeletal damage and reduce catabolic effects on the body’s protein reserves. However, correction needs to be done carefully, as over-alkalinisation can lead to complications.

If tolerated, judicious doses of potassium bicarbonate or potassium citrate may be of benefit.

Blood pressure

CKD is the most common cause of hypertension in both cats and dogs; therefore, monitoring and intervening where needed will help limit progression of end organ damage, such as retinal disease, and minimising further progression of CKD.

An angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, such as benazepril, is usually the first drug to be used in the management of feline and canine hypertension; however, it has a relatively mild effect on blood pressure. In cases with more significant hypertension, amlodipine is introduced and the dose titrated to effect.

An ACE inhibitor is also indicated when significant proteinuria is documented (an elevated urine protein:creatinine [UPC] ratio on the basis of IRIS guidelines).

Managing anaemia

Patients with CKD commonly develop anaemia of chronic disease through several mechanisms, including reduced red cell lifespan, blood loss and reduced production through inadequate renal production of endogenous erythropoietin (EPO).

In acute situations, blood transfusion may be considered; however, treatment usually focuses on trying to maintain red cell lifespan and minimise blood loss (omeprazole may be helpful in patients with uraemic gastritis).

Where red cell production in reduced and low endogenous EPO levels are suspected, supplementation with exogenous EPO analogues is often very successful in increasing red cell numbers and, therefore, improving patient quality of life.

EPO therapy is not without risks, as an immune response can occur against the exogenous EPO – leading to pure red cell aplasia. This complication can be reduced by the use of darbepoetin, which has an extended action and may be less immunogenic.

Iron status (evaluating reticulocyte haemoglobin) and blood pressure should be evaluated before commencing therapy with EPO.

Proteinuria

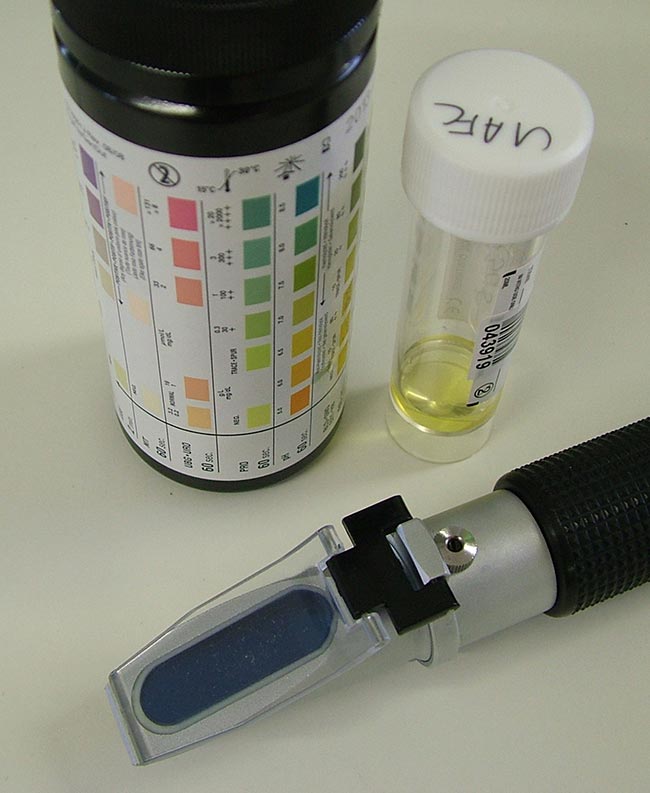

Patients with proteinuria should be evaluated for underlying causes, with treatment commenced to try to lower urine protein levels (Figure 2).

Causes of proteinuria – such as urinary tract infection or haemorrhage – may be easily identified; however, in more cryptic or unexpected cases, a renal biopsy may be suggested. Indications for this include renomegaly, CKD in a young patient, and persistent and severe proteinuria (UPC greater than 2.0) in a non-azotaemic patient.

Once proteinuria is confirmed, treatment with a renal diet is continued (essential fatty acids may help limit proteinuria) and an ACE inhibitor commenced. If proteinuria is not controlled with diet and an ACE inhibitor alone then an angiotensin receptor blocker is added.

If severe hypoalbuminaemia (albumin lower than 20g/L) is present, treatment with a platelet inhibitor, such as low-dose acetylsalicylic acid or clopidogrel, should be considered.

Hydration

Patients with CKD have reduced renal concentrating ability and frequently become dehydrated as a result, especially if they are also not eating. Having fresh drinking water available all the time will help.

Clinical dehydration and hypovolaemia need to be treated with isotonic, polyionic replacement fluid solutions (for example, Ringer’s lactate solution) IV or SC as required (Figure 3).

Low sodium-containing fluids and potassium-supplemented fluids should be used where possible.

Drug doses

It is important to note many drugs undergo renal excretion – and for many, dose adjustments are suggested where CKD is present; consult a formulary for specific drugs and dose/interval adjustments.

Alternatives should be sought to therapies that are known to be nephrotoxic – for example, the aminoglycosides and cisplatin.

Monitoring and outlook

The response to therapy should be carefully monitored – and initially, two-week to four-week revisits would be suggested. In the longer term, these may be of increased intervals.

We can do a lot for our geriatric patients with CKD – and they can be really rewarding patients to treat.

- Some drugs are not licensed for veterinary use.