10 Jan 2017

RVN Devon Caffull outlines various dental procedures often involving VNs and the significant contributions they can make.

Cat teeth.

Veterinary nurses have the capability to play a huge role in dentistry, which would not only save vets precious time, but also allow VNs themselves to be more fulfilled – and even specialise in this area, if they have a specific interest.

As long as a VN is confident in his or her capabilities, and recognises when a case needs to be referred to a vet, no reason exists as to why they cannot be heavily involved in dental procedures. This can include conducting oral assessments, scaling and polishing teeth, and/or radiography and suturing.

Nurse clinics are also vital post-dental procedures, to educate clients to ensure good care is maintained, but also to provide advice on preventive health care. This should ideally start while the patients are young – for example, at puppy/kitten parties or at six-month checks. This article discusses the stages of a dental procedure in practice and how the VN can be involved at each stage.

Keywords: dentistry, periodontal disease, radiography, client education, tooth assessment

Periodontal disease is a common health problem seen in both dogs and cats that can have a significant negative effect on their quality of life.

As a result, dental procedures to alleviate this pain are commonly seen in practice, and VNs can have a significant role in these.

A VN’s dentistry role starts right at the beginning – often at six-month check clinics or puppy parties. These are ideal situations to broach the subject of common health problems in dogs and cats – one of the biggest being periodontal disease. The clinics offer a relaxed atmosphere where clients can ask questions and VNs can demonstrate oral health care techniques, such as tooth brushing (McLeod, 2008), from day one.

Tooth brushing must be introduced to pets at a young age to let them become accustomed to the process and for it to be successfully introduced into their daily routine (Vranch and Tutt, 2009).

Once a vet has decided a dental procedure is necessary, a VN can play a large part in the procedure at a number of key stages.

A full and thorough examination of the oral cavity can only be carried out under anaesthesia. This should be the first stage in the process before any cleaning is done and involves assessing the cavity for a number of abnormalities, including:

Some of these abnormalities, such as calculus and gingivitis, can be given a score from zero (healthy) to three (heavy calculus/thickened or bleeding gingiva). Any abnormalities found must be accurately recorded on a dental chart.

Different types of charting methods exist and the type used is a matter of personal preference. However, a common one is the Triadan numbering system. This numbers the teeth to allow easy identification of where abnormalities lie within the oral cavity (Vranch and Tutt, 2009).

Once a chart has been accurately completed, scaling and polishing can be carried out. This should be done before extractions are considered, to allow better assessment of the teeth. The first step is supragingival cleaning, which involves removing plaque/calculus above the gingival line using a scaler (Niemiec, 2008). Niemiec recommended combined use of an ultrasonic scaler and hand scaler for best results.

This step alone is not sufficient in controlling periodontal disease, however. The next step is subgingival cleaning, which involves removal of calculus below the gingival line. This is more difficult as limited access and visualisation to the area exists and the gingival sulcus restricts movement of instruments.

Originally, the ultrasonic scalers commonly used in practice were not recommended for subgingival use as the vibration generated heat. With the coolant water unable to reach the tip, this resulted in thermal damage to the teeth and/or gingiva.

However, new tips have now been developed that lead water to the instrument tip, allowing their use subgingivally (Robinson, 2007).

The next stage of the cleaning process is polishing. Although often neglected in practice, this part is important as it smooths a tooth’s surface, retarding future plaque attachment (Niemiec, 2008). The aim of this is to smooth over any scratches you may have made during scaling, and it is important to use a sufficient amount of polish to stop overheating (Caiafa, 2007).

Niemiec (2008) recommended the final stage of cleaning to be sulcal lavage, which involves using a blunt-ended cannula to flush the gingival sulcus with saline or a 0.12% chlorhexidine solution. The aim of this is to dislodge microscopic debris that could otherwise be left in the sulcus.

Examination and probing, although helpful, do not reveal the full extent of periodontal disease. Therefore, a full set of dental radiographs should be obtained after cleaning and probing. X-rays can reveal (eMedia Unit RVC, 2002):

With practice, VNs can quickly obtain a set of full mouth x-rays with minimal effort (Tsugawa and Verstraete, 2000). Although standard x-ray units and films can be used to gain intraoral views, their use is limited and, therefore, not recommended. They are also not commonly in a convenient location for use in a dental procedure.

Ideally, a specialised dental x-ray machine – which is quite small, so can be placed in the dental room, as well as be wall-mounted – should be used, an example of which is shown in Figure 1. They are easily manoeuvrable and have a set kilovoltage and milliamperage, so only the time of exposure needs to be set.

Furthermore, if combined with a charge-coupled device/complementary metal oxide semiconductor sensor plate system and computer, the image can be automatically displayed on the computer screen and viewed immediately. This system is ideal, as images can be saved and attached to patient records, then can be kept for reference, shown to owners or sent to referral centres (eMedia Unit RVC, 2002).

A combination of two techniques should be used to acquire a full set of dental x-rays. The parallel technique places the film parallel to the tooth’s long axis with the x-ray beam perpendicular to the film. This is suitable for molars/premolars (Tsugawa and Verstraete, 2000). Figure 2 shows a cat having a dental x-ray taken using the parallel technique.

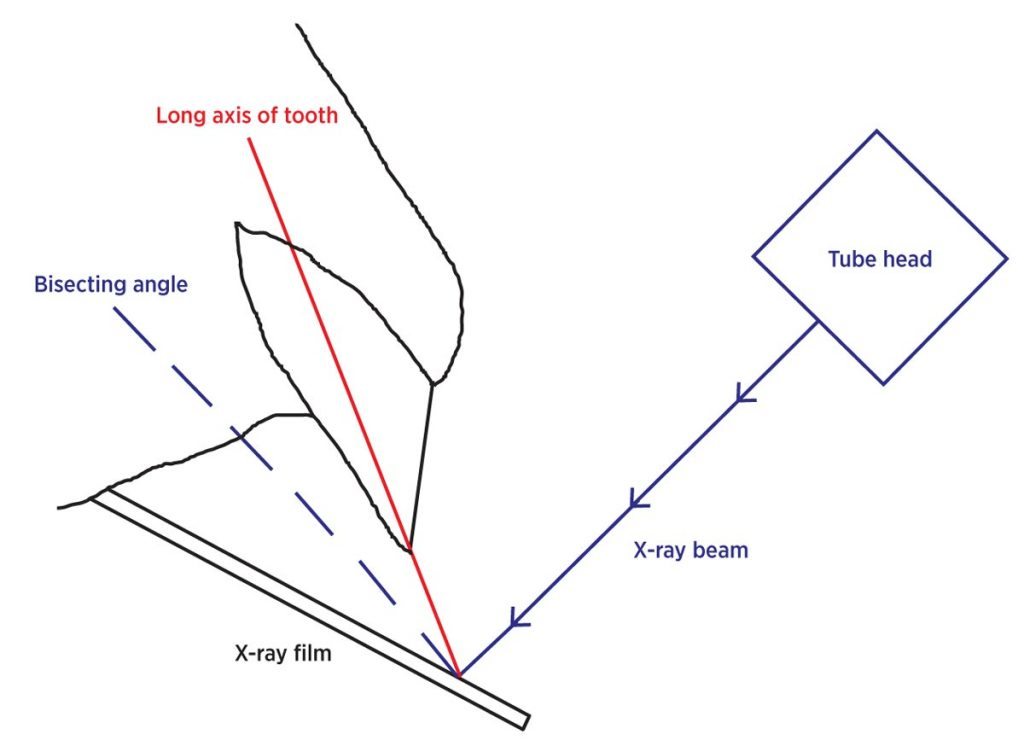

If the angle between the tooth and the dental film is more than 15°, the bisecting technique should be used (eMedia Unit RVC, 2002). This involves placing the film as close to parallel to the tooth’s long axis as possible and the x-ray beam perpendicular to the line that bisects the angle between the tooth axis and film. This technique prevents the image being elongated/shortened and is more suitable for incisors/canines (Tsugawa and Verstraete, 2000). Figure 3 is a diagram of how this technique is used.

One extra technique that may be needed is the extraoral near parallel technique. This should be used for the maxillary cheek teeth if superimposition of the zygomatic arch is a problem, which it often is in cats. This involves the patient lying in lateral recumbency with the maxillary cheek teeth being x-rayed closest to the table. The mouth should be held open and the film placed as near to parallel to the long axis of the teeth as possible. The beam is then angled 70° to the film and target teeth.

VNs are governed by the Veterinary Surgeons Act (1966) and subsequent amendments, which detail what they are legally allowed to do. This act states no one other than an registered veterinary surgeon should practise veterinary surgery.

A more recent amendment was the addition of Schedule 3, which states medical treatment or minor surgery (not involving entering a body cavity) can be carried out by a nurse only if:

VNs are also governed by the RCVS Code of Professional Conduct, which gives ethical guidance to the profession. It states VNs have an ethical duty to comply with the aforementioned legislation and an ethical obligation to keep within one’s own area of competence and refer cases accordingly (RCVS, 2012a).

Therefore, legally and ethically, no reason exists – as long as both the nurse and vet are happy – as to why nurses shouldn’t have a major role in dentistry. With the aid of a second nurse monitoring the patient’s anaesthetic, they can chart, scale, polish, x-ray and assess the teeth. However, a nurse is not allowed to extract teeth using instruments.

Therefore, if assessment concluded extractions were needed, a vet should take over the procedure (RCVS, 2012b). Once the necessary extractions have been performed by the vet, any suturing of the extraction site can then be completed by the nurse, as long as they felt competent in doing so (RCVS, 2012a).

As important as these dental procedures are, they are really only part of the story in providing good quality care for patients. A home care plan must be devised and discussed with the owner to ensure continuing control of periodontal disease (Figure 4).

In fact, it has been shown that if a home care plan is not implemented, a patient’s gingivitis score could return to its original level of severity as early as three months post-surgery.

One of the main parts of a good home care plan is tooth brushing. This is the most effective method of plaque control, but must be carried out daily. Pet toothpastes can be used, but are not essential (Vranch and Tutt, 2009).

The patients likely to be seen at postoperative dental checks are likely to be older animals that may not tolerate the introduction of tooth brushing if they are not already familiar with it (Vranch and Tutt, 2009).

Dental chews can be recommended as an alternative to aid the reduction of plaque accumulation. However, they are not as effective as tooth brushing and, if fed in addition to a patient’s normal diet, can cause weight gain.

Therefore, the owner must be warned to appropriately reduce the daily food amount, if supplementing the diet with chews.

Specially designed diets are also available that aim to promote good dental health. They tend to have larger, more fibrous kibbles that maintain maximum contact with the tooth surface to mechanically remove plaque (Bloor, 2014).

Clients should be encouraged to continue to attend dental clinics postoperatively to monitor their pets’ general dental health and re-enforce or re-demonstrate techniques previously shown (Vranch and Tutt, 2009).

With practice and training, VNs can become a time-saving asset to vets when completing dental procedures. They also have a key involvement in client education regarding oral hygiene for pets.

Devon Caffull

Job Title