17 Apr 2017

Solving an emergency canine case

John Williams reports on a case where a border terrier was presented at an emergency hospital and how diagnosis was made.

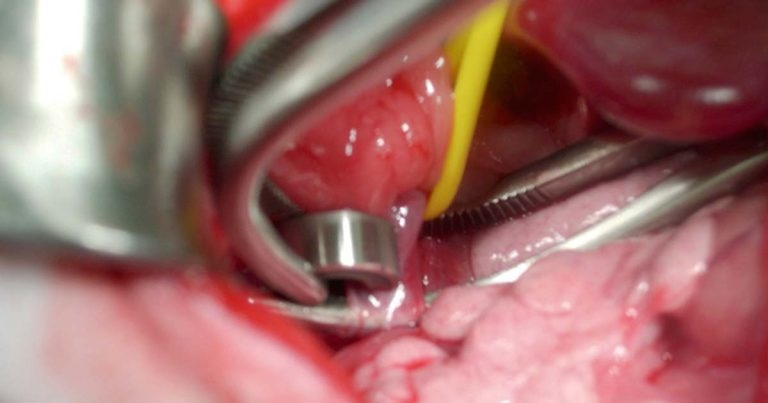

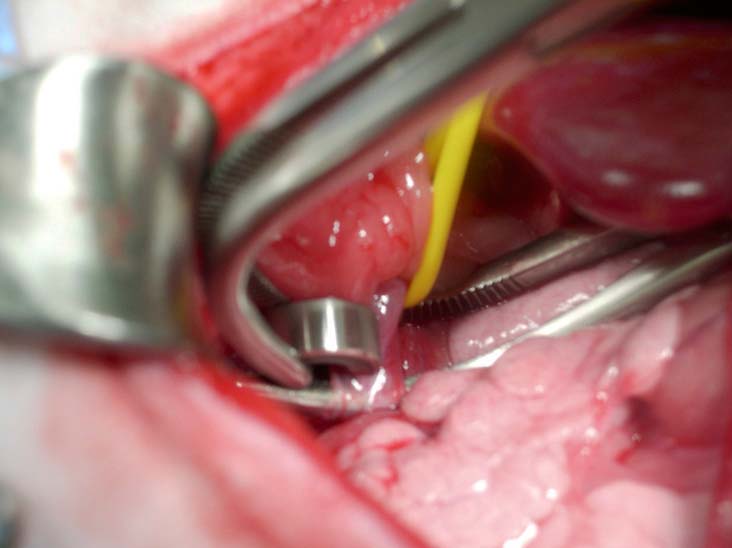

Figure 6. An ameroid constrictor placed around the shunt vessel.

Eric, a four-month-old border terrier (Figure 1), presented late one night to the emergency and critical care (ECC) department of the Vets Now Emergency and Specialty Hospital, Manchester. Eric had been unwell for several days prior to presentation, as he was not eating as well as previously and became increasingly listless.

On the day of presentation, he had not eaten at all, was hypersalivating and was noted to have been pacing relentlessly. As the day wore on, he became disorientated and his owners reported he was walking into furniture. At about 8pm he “collapsed” and was seizuring; his owners then contacted the hospital.

At presentation to a colleague in ECC, Eric was comatose and exhibiting muscle tremors. Clinical examination revealed he was small and underweight for his age (body condition score of four), cryptorchid, his temperature was 37.2°C, his heart rate was 120bpm and pallor of his mucous membranes was noted.

After careful questioning by the triage nurse, it became evident Eric had been a “poor doer” since the owners obtained him at eight weeks of age. He was fully vaccinated and had been “wormed”. They reported his appetite was inconsistent, he would frequently show “odd” behaviour, including pacing around a room and hiding in dark areas, was subject to intermittent bouts of vomiting and diarrhoea, and he drank more water than they expected a pup to do. His episodes of “odd” behaviour would frequently occur after a meal. No access to toxins was known and trauma was not reported.

Early diagnosis

Based on presentation, the main differential diagnoses using the “damn it” mnemonic are:

- degenerative

- storage disorder

- metabolic

- hepatic encephalopathy (HE) secondary to portosystemic shunt or juvenile hepatopathy

- hypoglycaemia

- electrolyte anomaly, such as hypoadrenocorticism

- nutritional

- hypoglycaemia

- idiopathic

- epilepsy

- toxic

- lead

- drug related

- exposure (poisoning)

- traumatic

- acute

- delayed

The ECC clinician took the view the main concern was to stabilise Eric and formulate a definitive diagnosis later. However, from the differential diagnoses, HE was deemed to be the most likely until proven otherwise. Blood was taken for analysis at the same time as management was initiated.

Initial stabilisation was aimed at minimising risk of airway aspiration due to Eric being comatose; propofol was drawn up at 0.5mg/kg and administered IV to effect, to allow intubation. This had a twofold effect in allowing control of the airway, and propofol has been shown to be beneficial in controlling some cases of hepatic encephalopathy seizures; the propofol was continued as a constant rate infusion (CRI; at 0.05mg/g/min to 0.1mg/g/min).

As Eric was able to breathe normally at this stage, he was not ventilated, but his end-tidal CO2 was monitored. Consideration was given to giving flumazenil, an IV benzodiazepine receptor antagonist; however, its use is still controversial and may have little real benefit unless the patient is already on benzodiazepines. It is worth noting the ECC team did not consider using either diazepam nor midazolam, as some evidence exists they may exacerbate seizuring in HE patients (Lidbury et al, 2016). The team did consider using the renally excreted levetiracetam, but experience of using it suggested the onset was not rapid enough for Eric’s condition.

The initial blood results on Eric showed a mild hypokalaemia, a hypoalbuminaemia, a low BUN and hyperammonaemia, which were consistent with HE. Based on the results, Eric was given IV 0.95 sodium chloride with 5.5 per cent glucose monohydrate and was supplemented with 7mmol per 250ml potassium chloride. Blood potassium and glucose were checked regularly while he was comatose and the potassium supplement reduced when necessary.

Treatment and diet management

As the primary concern (pending results) was a severe encephalopathic crisis, antibiotic was administered IV (co-amoxiclav at 22mg/kg) as Eric could not be given oral therapy (to be repeated every eight hours). A 30-minute retention lactulose enema was given via a Foley catheter with 3ml of lactulose mixed with 27ml of water. Care must be taken that too much lactulose is not used, as it may lead to electrolyte disturbances. Eric was written up for 50ml warm water enemas every four to six hours until oral administration of lactulose was possible. Omeprazole was given IV every eight hours, as a risk of gastrointestinal ulceration exists in such cases.

The full biochemistry and haematology panel showed an elevated alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase, and a moderate leukocytosis, together with a mild microcytic, normochromic, nonregenerative anaemia. These changes indicated further testing would be required to drill down the diagnosis.

Eric’s propofol CRI was slowly withdrawn after 12 hours when he regained consciousness and did not show any signs of seizuring. He was initially ataxic and blind (the amaurosis persisted for a further 48 hours). Though still on IV fluids, the ECC clinician decided to put Eric on oral medication and start a suitable diet to control his HE in the short to medium term.

Co-amoxiclav was prescribed at 12.5mg/kg twice a day and lactulose at 5ml every eight hours. The dose of lactulose would be titrated to effect and raised or lowered as needed, until Eric passed three to four soft, but formed, stools per day. It should be noted neither metronidazole or neomycin were prescribed, as metronidazole may lead to signs similar to HE and neomycin; even taken orally it can lead to nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity. The omeprazole was also changed to oral dosing three times a day.

As diet plays a large part in precipitating HE, careful thought was given as to what to feed Eric. Care must be taken with protein load, but severe protein restriction is not recommended for dogs as it can cause protein malnutrition. A commercial diet that contained 14 per cent to 18 per cent protein on a dry matter basis was chosen as it also had restricted copper and sodium content, and with supplemented zinc and antioxidants. Once stable the protein content could be further increased by adding soya-based protein.

Three days after presentation, Eric was bright, alert and very active. As he was eating well, pre-prandial and post-prandial bile acid levels were assessed. His pre-prandial level was 35μmol/L (reference range below 10μmol/L) and post-prandial 160μmol/L (reference range below 25μmol/L). This suggested hepatic dysfunction with a portosystemic shunt being the most likely diagnosis. Following a case conference between the ECC and surgery clinicians, it was decided rather than investigate further with abdominal ultrasound or CT scan (both requiring sedation), Eric would be discharged on a three-week course of antibiotics, lactulose and the commercial hepatic support diet.

Figure 2 is a 3D reconstruction of the contrast CT study. The portocaval shunt vessel is arrowed where it joins the caudal vena cava.

After three weeks (Figure 3), Eric returned to the clinic. He was still very bright and active, and had no further episodes of HE. He was sedated and underwent a contrast CT scan, which showed a portocaval portosystemic shunt.

Eric was transferred to the surgical team, as evidence indicated surgery had a better long-term outcome (Greenhalgh et al, 2010; Thieman Mankin, 2015). In addition to his ongoing medication, levetiracetam was prescribed at 20mg/kg every 8 hours, starting 48 hours preoperatively. Some evidence exists this may help prevent post-surgical seizuring (Fryer et al, 2011).

Ready for surgery

Due to Eric’s age and diagnosis, he was fed up until four hours preoperatively. Once the anaesthetic checklists (identified patient and procedure, checked his weight and calculated drug dosages, including any required for resuscitation) was completed, Eric was scheduled for blood glucose checks every 30 minutes during the procedure and until he was eating post-surgically. He was premedicated with methadone and anaesthesia was induced with IV propofol, titrated to effect.

For surgery, Eric was placed in dorsal recumbency and the abdomen was clipped from 3cm cranial to the xiphisternum to caudal inguinal area. The skin was prepped prior to be taken into theatre. In theatre, a surgical checklist was completed, which included checking swab numbers, an instrument count and making sure all the required instrumentation was available and working.

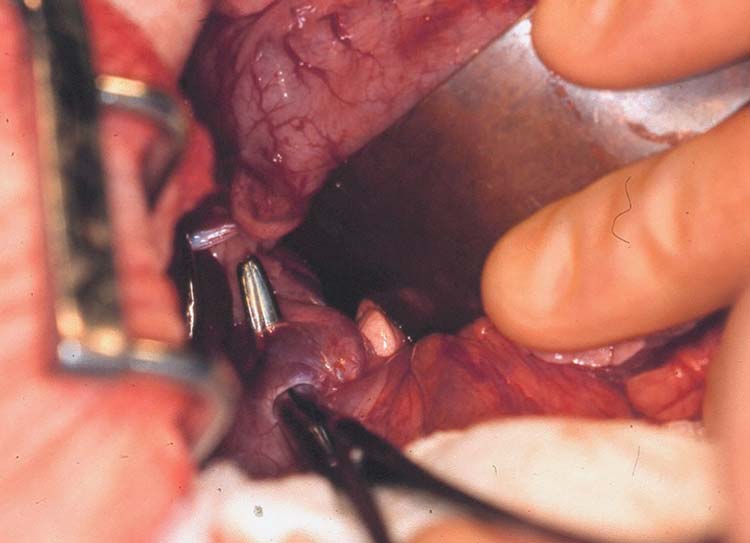

Once fully draped, a midline coeliotomy was carried out and the falciform fat was excised with the aid of diathermy. A duodenal manoeuvre was carried out to view the epiploic foramen and the portocaval shunt was confirmed at that level. The omental bursa was divided to allow improved access to the shunt vessel. Lahey bile duct forceps were used to bluntly dissect around the vessel as close as possible to the caudal vena cava; once a “tunnel” had been created, a right-angled tonsillectomy clamp was passed around the vessel (Figure 4).

The jaws of the tonsillectomy clamp were opened, which caused the shunt vessel to collapse. The intestines and pancreas were assessed for evidence of portal hypertension, which was immediately evident. The jaws of the clamp were closed and the portal hypertension improved. The jaws were opened again – this time wide enough to allow a 3.5mm ameroid constrictor to be placed around the vessel (Figures 5 and 6).

Once the constrictor was applied over the flattened shunt vessel, the tonsillectomy clamp was withdrawn. The vessel re-expanded apart from the narrowing as it passed through the ameroid constrictor. Circulation was allowed to equilibrate for more than five minutes, with no evidence of portal hypertension. At this point, the key was inserted into the ameroid constrictor to prevent it from slipping from the shunt vessel (Vogt et al, 1996).

Abdominal closure was routine, with continuous 3 metric polydioxanone in the linea alba and a continuous horizontal mattress suture of barbed 2 metric 90 glycomer 631 placed intradermally. A nonadherent dressing was secured over the wound.

Eric made an excellent recovery from surgery and was eating well two hours later. In addition to his ongoing medications, he was pain scored and methadone was given initially, which was changed after 12 hours to buprenorphine. He was kept in hospital for three days to monitor for any potential post-surgical seizures.

Eric was discharged on a six-week course of medication and diet as the ameroid constrictor can take up to six weeks to attenuate the shunt vessel (Hunt et al, 2014). At his six-week check he was happy, bright and eating well, his oral medication was stopped and the owners advised to introduce a normal diet over a two-week period. Eric is due a further check, but he will not have his bile acid levels checked as poor correlation exists between post-surgical levels and outcome.

The success for Eric is reinforced by the team ethos of working in a 24/7 ECC and specialty hospital that allows for critical cases to be seen at any time of day or night and managed by the ECC team until it can be transferred to the necessary discipline for definitive management.

- Some drugs mentioned have been used under the cascade.