24 Feb 2025

Specialist testing for pets’ difficult endocrine diseases

Helen Evans BSc(Hons) explores the specific steps required for diagnosing insulinomas in dogs and cats

Image: Кристина Корнеева / Adobe Stock

Endocrine diseases pose significant diagnostic challenges in veterinary medicine.

Clinical signs are often subtle and non-specific, and one endocrine disorder may predispose to another. It is, therefore, not uncommon for more than one condition to be present concurrently, further complicating the diagnosis.

Specialist endocrinology testing plays a vital role in helping to diagnose these complex cases – especially when clinical signs and initial testing fail to provide diagnostic clarity. This article focuses on a particularly challenging area: the diagnosis of canine insulinomas.

Common pancreatic tumours

Insulinomas are functional neuroendocrine tumours originating from pancreatic beta cells. Although insulinomas are considered to be rare, they are the most common pancreatic tumour in dogs and predominantly affect medium to large breeds, with the German shepherd, boxer, golden retriever and Labrador retriever showing increased predisposition1.

Although no definitive histological criteria exist for malignancy, insulinomas are usually associated with metastasis, and approximately 95 per cent of canine insulinomas are considered malignant2.

Pathophysiology

In healthy patients, blood glucose regulation involves close hormonal control, with insulin secretion rates responding to changes in blood glucose concentration. When blood glucose concentrations rise, an increase occurs in the rate of glycogenesis and a corresponding increase in insulin secretion by beta cells.

Equally, when blood glucose concentrations decrease, insulin synthesis and secretion is inhibited, limiting tissue utilisation of glucose and allowing blood glucose concentrations to increase. Counter-regulatory hormones include glucagon and adrenaline, released in the immediate term, and cortisol and growth hormone, which are involved in longer-term control.

In cases of insulinoma, the pancreatic beta cells are unresponsive to hypoglycaemia and counter-regulatory control, resulting in uncontrolled secretion of insulin and profound hypoglycaemia. The precise mechanisms underlying the excess insulin secretion by insulinomas and the impaired cellular response to hypoglycaemia are not well understood. However, recent research suggests up-regulated glucokinase expression may be an important factor3.

Clinical signs of insulinoma

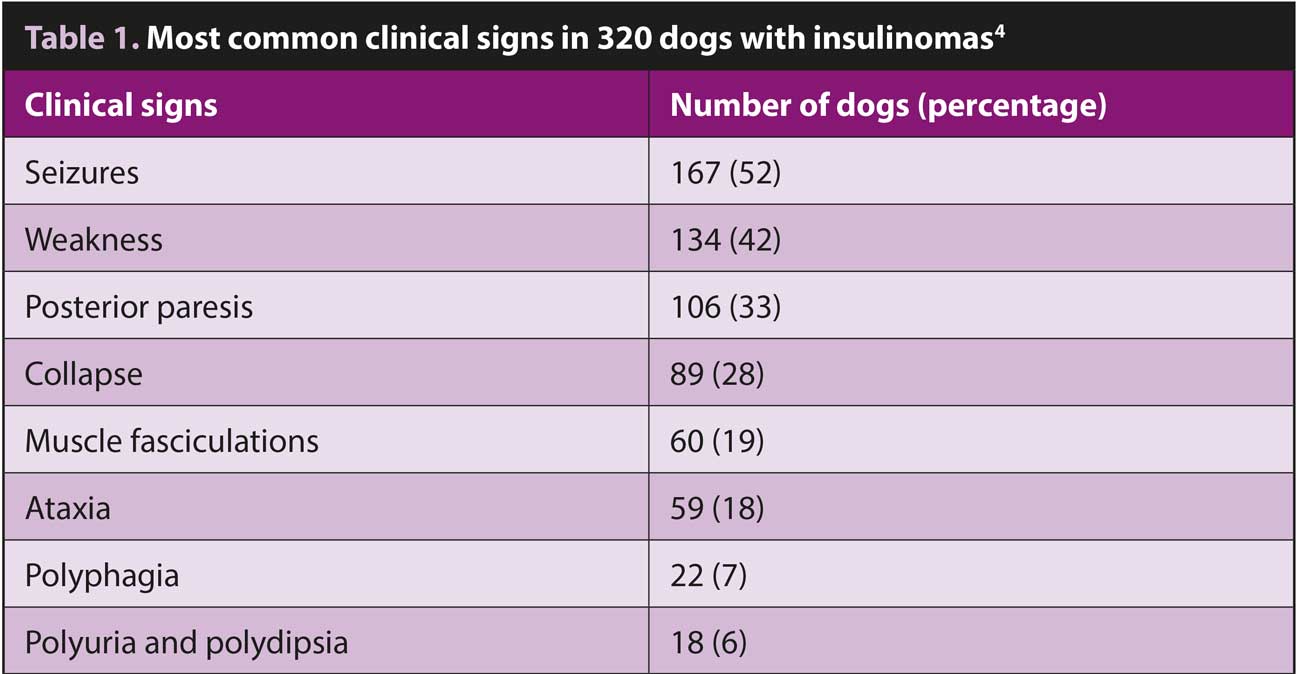

The clinical signs of insulinomas are related to the associated hypoglycaemia. Glucose is the primary energy source for the brain and nervous system and – in a hypoglycaemic patient – low blood-glucose results in reduced diffusion of glucose across the blood-brain barrier. This has a particularly profound impact on the nervous system and the most common clinical signs reflect this (Table 1).

Seizures, weakness and collapse are typically seen. Muscle tremors, nervousness and hunger may also occur due to a hypoglycaemia-induced activation of the autonomic nervous system.

In the early stages, signs may only be seen following fasting, exercise or excitement, and affected dogs will be clinically normal between episodes.

Diagnostic challenges

Due to the intermittent and non-specific nature of the clinical signs, insulinomas present significant diagnostic challenges.

Demonstrating inappropriate insulin secretion can also be technically challenging, as blood glucose concentrations may be normal at the time of sampling. Additionally, multiple other causes of hypoglycaemia must be ruled out, including sepsis, hepatic disease and hypoadrenocorticism.

Even when hypoglycaemia is documented and other differential diagnoses have been excluded, the interpretation of insulin results can be complex.

Blood biochemistry

Insulinoma is usually diagnosed by biochemical testing following a high level of clinical suspicion4. Routine bloods may show hypoglycaemia and, as discussed, are essential for ruling out other causes of hypoglycaemia.

Historically, a diagnosis of insulinomas was based on signalment, clinical history and the presence of Whipple’s triad, namely:

- hypoglycaemia

- clinical signs associated with hypoglycaemia

- resolution of signs after feeding (or glucose administration)

However, Whipple’s triad is non-specific and will usually be present in all cases of hypoglycaemia, whatever the underlying cause. Specialist endocrinology testing can provide a more sensitive and specific next step in the diagnostic pathway.

Initial steps

While insulinoma is typically associated with low blood glucose, it is important to note that normal blood glucose does not necessarily rule out the condition. Especially in the early stages of disease, hypoglycaemia may be intermittent and a fasted sample is often required.

Fasting should be carried out under careful clinical supervision, with regular monitoring of blood glucose concentrations.

Fasting insulin

The next step in the diagnosis of insulinoma requires demonstration of simultaneous low blood glucose and an inappropriate normal or elevated insulin.

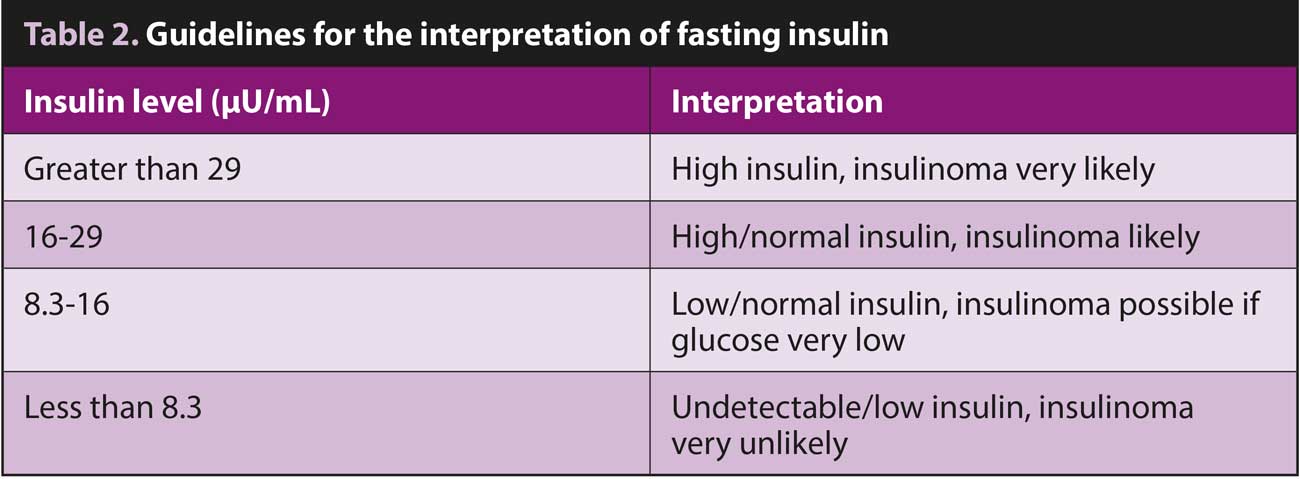

Samples for insulin assay should be taken after fasting or during a period when the blood glucose is known to be low. When interpreting fasting insulin, levels greater than 29muU/mL in a hypoglycaemic patient are considered diagnostic for insulinoma. Interpretation becomes more nuanced with intermediate results (Table 2), and repeat estimation of borderline results may be required to confirm the diagnosis.

Insulin:glucose ratio for borderline cases

In more nuanced cases, where absolute insulin values fall into borderline ranges, the insulin:glucose ratio (IGR) can provide additional diagnostic clarity. This ratio is particularly valuable when absolute hyperinsulinaemia (insulin level more than 29muU/mL) is not present, but clinical suspicion remains high. The IGR is calculated using simultaneously collected glucose and insulin samples, with the following formula:

IGR (UI/mol) = serum insulin (muU/mL) / serum glucose (mmol/L)

IGR greater than 7U/mol in a patient with low or low-normal glucose is consistent with insulinoma. However, it is important to note that an elevated ratio in an animal with high-normal or high glucose suggests insulin resistance rather than insulinoma, highlighting the importance of considering these results in clinical context.

Amended IGR for equivocal results

For cases that remain diagnostically challenging, the amended insulin:glucose ratio (AIGR) may provide additional insights. The AIGR uses a modified formula:

AIGR (UI/mol) = serum insulin (MuU/mL) × 100 / (serum glucose [mmol/L] × 18.02) – 30

This ratio was developed based on the principle that insulin levels should be undetectable when blood glucose is less than 30mg/dL (1.7mmol/L). An AIGR greater than 50 in a patient with subnormal blood glucose is consistent with an insulinoma diagnosis. This alternative calculation can be particularly helpful in cases where the standard IGR results are equivocal or when blood glucose levels are very low.

The AIGR should always be interpreted alongside other clinical and laboratory findings as part of a comprehensive diagnostic approach.

What about fructosamine?

While insulin and glucose measurements provide crucial diagnostic information for suspected insulinoma cases, fructosamine testing can offer additional insights while also serving as a valuable tool for investigating other pancreatic endocrine disorders. Fructosamine, formed by the non-enzymatic glycation of plasma proteins, reflects the mean blood glucose concentration over the previous one to three weeks. In cases of insulinoma, fructosamine may be decreased due to chronic hypoglycaemia. While this finding can increase clinical suspicion, it is not diagnostic in isolation.

Fructosamine is more useful for monitoring diabetic patients. However, when interpreting results in diabetic patients, it is crucial to understand that the laboratory’s normal reference range does not apply. In fact, a diabetic patient with fructosamine values falling within the normal reference range is likely experiencing concerning periods of hypoglycaemia.

For appropriate monitoring of diabetic control, species-specific target ranges should be used: in feline patients, fructosamine levels greater than 550mumol/L are consistent with poor diabetic control while the equivalent figure for canine patients is 450mumol/L.

The role of diagnostic imaging

While laboratory testing is crucial for diagnosing insulinoma, diagnostic imaging plays a vital role in surgical planning and determining prognosis.

Abdominal ultrasonography, while commonly used as an initial imaging modality, has limited sensitivity, detecting only about 36 per cent of insulinomas5 – largely due to their small size.

Computed tomography has emerged as the imaging modality of choice, offering superior detection rates and the ability to identify metastatic disease. However, it is important to note that imaging findings should always be interpreted alongside biochemical test results, as false positives and negatives can occur.

The diagnosis of many endocrine disorders is challenging. Non-specific clinical signs combined with the fact that a number of endocrine disorders may occur concurrently, means that specialist endocrine tests are often integral to reaching a definitive diagnosis.

Early diagnosis and early intervention almost always improves prognosis, and knowing when to use these specialised tests is essential.

Top tips for diagnosis of insulinomas

- Collect blood samples when blood glucose is known to be low.

- Multiple measurements may be needed in borderline cases.

- Consider insulin:glucose ratio and amended insulin:glucose ratio when absolute insulin levels are equivocal.

- Fructosamine can support diagnosis, but is not definitive.

- Imaging is essential for treatment planning.

- Helen Evans has a background in biological sciences and began her career developing assays at St Thomas’ Hospital in London. She then transitioned to a veterinary clinical laboratory, a setting where she spent over 20 years. As a co-founder and a manager at NationWide Specialist Laboratories, Helen has successfully grown the laboratory, offering unique assays. With extensive expertise in endocrinology, biochemistry, and veterinary medicine, Helen provides valuable insights in her field.

- Article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 6, Pages 6-8

References

- Mullin C and Clifford CA (2017). Canine insulinoma, Clinician’s Brief, tinyurl.com/3ewhrpsb

- Buishand FO and Scudder CJ (2023). Advances in diagnosis and management of canine insulinoma: a review, Companion Animal, tinyurl.com/ynmdedm8

- Suwitheechon O-U and Schermerhorn T (2021). Evaluation of the expression of hexokinase 1, glucokinase, and insulin by canine insulinoma cells maintained in short-term culture, American Journal of Veterinary Research 82(2): 110-117.

- Buishand FO (2022). Current trends in diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of canine insulinoma, Veterinary Sciences 9(10): 540.

- Robben JH, Pollak YWEA, Kirpensteijn J et al (2005). Comparison of ultrasonography, computed tomography, and single-photon emission computed tomography for detection and localization of canine insulinoma, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 19(1): 15-22.