22 May 2020

Spotting the signs of canine epilepsy and management advice for owners

Sergio Gomes and Mark Lowrie describe the classifications and manifestations of this condition, as well as current insights, treatment objectives, and conventional and alternative therapies.

A seizure is a paroxysmal and transient event where spontaneous abnormal electrical activity within the cerebral neurons leads to variable sensory, motor and autonomic events (Podell, 1996; March, 1998).

Epilepsy as a disease describes a persistent predisposition of seizure generation within a brain (Fisher et al, 2014).

Classification into the aetiology and manifestations has been the focus of constant debate within veterinary medicine.

The commonly used terminology and most recent consensus in classification are summarised. More importantly, a series of articles by the International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force (IVETF) compiled a general consensus in many questions relating to canine idiopathic epilepsy, including nomenclature, classification and indications for treatment (Berendt et al, 2015; Bhatti et al, 2015; De Risio et al, 2015).

Some of these updated recommendations are compiled in this article, together with the authors’ experiences – particularly when distinguishing epileptic seizures from other paroxysmal events.

Seizures

Seizure frequency is described as isolated if a single self‑resolving episode occurs; cluster seizure when two or more occur over a period of 24 hours; and status epilepticus when a single or sequential seizure occurs continuously without a normal interictal period.

A summary of the most recently proposed classification of seizure manifestations is presented in Table 1.

| Table 1. Classification of seizures – adapted from the International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force (Berendt et al, 2015) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Generalised epileptic seizure1 | Focal epileptic seizures | |

| Consciousness | Generally lost (retained in the myoclonic form) | Retained |

| Body part involvement | • Bilateral (for example, tonic-clonic pedalling movements in all four limbs) • Generally accompanied with salivation, urination and/or defecation |

Lateralised or regional (for example, muscular tremors, hypersalivation, behavioural) |

| Further classification | • Convulsive generalised epileptic seizures: ▪ tonic • Non-convulsive generalised epileptic seizures: ▪ atonic/”drop attacks” (sudden and general loss of muscle tone) |

• Motor (for example, facial twitches, blinking) • Autonomic (for example, vomiting, hypersalivation) • Behavioural (for example, attention-seeking, restlessness) |

| 1 Occurring alone or evolving from a focal epileptic seizure start. | ||

Epilepsy

Epilepsy has been defined as chronic recurrent seizures. Given a large number of causes exist for chronic recurrent seizures, epilepsy is not a specific disease, but a group of heterogeneous disorders.

Having said this, not all seizures are associated with epilepsy. A common example of this is with reactive seizures, which represent a usually reversible reaction of normal brain to a transient systemic insult or physiologic stress, such as in hepatic encephalopathy (Podell, 1996).

Given the seizure will cease when the metabolic or toxic disorder is resolved, the patient is not considered to have epilepsy.

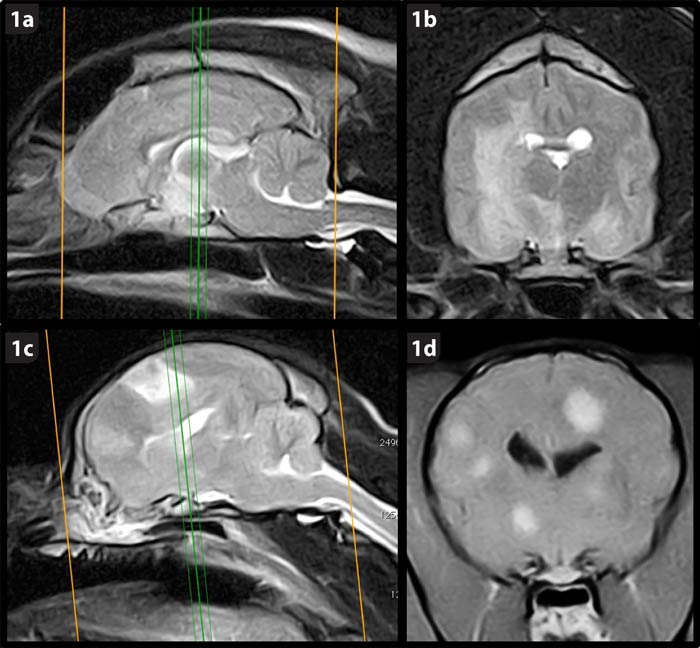

Aetiologically, epilepsy can be classified as structural and idiopathic. Structural epilepsy relies on the existence of a lesion within the cerebral parenchyma, such as in the case of brain tumours or meningoencephalitis of unknown origin (Figure 1). Idiopathic epilepsy is a diagnosis of exclusion when diagnostic investigations have ruled out reactive or structural causes for the seizures.

Diagnostic investigations should include haematology, a full biochemistry with particular attention to renal and hepatic function, preprandial and postprandial bile acid concentrations, a fasting glucose concentration and electrolytes.

MRI of the brain ruling out structural lesions is particularly important in animals younger than one year of age and older than six years of age, as idiopathic epilepsy is most frequently encountered between this age range (Figure 2).

However, it is important to undergo advanced investigations – including MRI and CSF analysis – in cases where interictal abnormalities, such as proprioceptive deficits or ataxia, are noticeable.

Current insights

Are these real epileptic seizures?

Identifying epileptic seizures can be a challenging task for veterinarians – particularly when based solemnly on the owner’s description.

Although this has not been assessed in veterinary medicine, in humans – where precise symptom description is obtained from the patient – about 20% of cases of suspected epileptic seizures can be misdiagnosed incorrectly as epilepsy (Zaidi et al, 2000).

Whenever possible, video footage of the event should be retrieved from the owners, as specific traits may be made clearer and owner descriptions can be ambiguous.

Common presentations that can be easily mistaken as an epileptic seizure include syncope, movement disorders and stereotypical behaviour disorders.

Typically, generalised epileptic seizures involve an impaired – or loss of – consciousness and cannot be interrupted by the owners, either by touch or calling the pet’s name (Table 1). This is in contrast to cases of compulsive behaviour – for example, tail chasing – whereby owners are commonly able to interrupt the episodes, either by manipulating or calling the pet’s name.

Syncope occurs secondarily to a sudden interruption of the normal blood supply containing nutrients or oxygen to the brain, and it is usually short-lived (30 seconds). It is also usually characterised by flaccid collapse, and a return to normal behaviour is expected almost immediately.

Syncope is typically related to periods of exercise, while a generalised epileptic seizure will more commonly manifest itself during sleep or rest (Charalambous et al, 2017).

Movement disorders (also termed paroxysmal dyskinesia) consist of a variety of sudden, transient episodes and manifestations, including excessive muscle tone, generalised tremors, myoclonus (jerky movements) or episodes of stiffness (Lowrie and Garosi, 2017).

Breed-specific examples of these disorders are the paroxysmal gluten-sensitive dyskinesia in border terriers (previously termed canine epileptoid cramping syndrome or Spike’s disease) and episodic falling syndrome in cavalier King Charles spaniels (or hypertonicity syndrome).

Although these episodes cannot be interrupted by the owners, the animal retains consciousness despite motor manifestations in all four limbs, and the duration – despite being variable – can be many times longer than that of a typical generalised seizure with no postictal period.

Video footage is extremely useful in these cases, as details such as impaired consciousness, postictal phase or triggers can be assessed by the veterinarian, rather than a reliance on owner description.

Treatment

Idiopathic epilepsy is not medically curable; however, antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) can be prescribed aimed at reducing seizure frequency and severity.

Indications for treatment

Indications for therapy initiation, based on the IVETF consensus, are based on the presence of one of the following criteria:

- when two or more epileptic seizures occurred within a six‑month period

- presence of status epilepticus or cluster seizures

- presence of long (more than 24 hours) or severe postictal signs (for example, aggression)

- evidence of increasing frequency or duration over three consecutive seizures (Bhatti et al, 2015)

These are good indicators in most cases; however, treatment recommendations should be tailored according to each patient’s particularities (for example, concomitant hepatic or renal disease), but also managing the owner’s expectations.

Treatment objectives

The aim of the treatment should be to reduce the frequency, duration or severity of seizures, keeping in mind the animal’s quality of life by limiting adverse drug effects.

Usually, a reduction of 50% or more in the frequency of seizures is sought for the treatment to be deemed successful. However, a reduction of the episodes or limiting postictal changes – such as drowsiness or aggression – is also an objective of the treatment.

Client compliance is fundamental, and all efforts should be made to ensure medication is given appropriately, consistently and at the right dosage.

General recommendations on seizure management should be provided, such as minimising stimuli during the events (for example, switching off lights and eliminating noises), as well as recognising the presence of postictal behaviours – such as aggressiveness or reclusion – as part of the disease.

It is particularly important owners are made aware that sudden interruption of treatment can lead to increased seizure activity and that medication will be, in most cases, a lifelong concern.

Conventional therapy

Medication is widely accepted as the cornerstone of treatment for idiopathic epilepsy in veterinary medicine. This involves increasing the threshold required for seizure onset and decreasing the spread of the abnormal electrical activity to surrounding neurons in the forebrain.

Monotherapy is usually attempted initially, with additional medication being given (commonly concurrently) in refractory cases.

The authors discuss some of the most typically used first‑line AEDs – selection of which relies on the prescription cascade, its availability in the UK, as well as their current evidence of effectiveness.

Alternative therapies

Ketogenic diet

Dietary manipulation has been attempted as an adjunctive method in the management of epileptic dogs, with variable results.

Ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-protein diet that can simulate the same metabolic state as fasting in humans, leading to reduced frequency of seizures in infants.

A study has investigated its adjunctive effects in refractory epileptic dogs already receiving antiepileptic medication. A diet trial based on a formulation rich in medium-chain triglycerides demonstrated a reduction in seizure frequency, when compared to a placebo diet, in 70% of cases over the course of a three-month period in a population of 21 dogs (Law et al, 2015).

Although potentially promising, further studies with a larger population and longer follow-up time are needed.

Vagal nerve stimulation

Vagal nerve stimulation relies on the surgical implantation of a device delivering repetitive electrical impulses to the vagal nerve. This has shown to successfully reduce seizure frequency in humans; however, it has not yet been proven to be of benefit in dogs.

Surgical implantation in dogs has been shown to be possible; however, it has not been reported to have a positive effect (Muñana et al, 2002).

Surgical complications, as well as prohibitive prices, means this is yet to be a feasible treatment in dogs.

Acupuncture

Current knowledge does not unequivocally support the use of acupuncture in the treatment of epilepsy in either human or veterinary medicine. However, some studies revealed some benefit of acupuncture, when used as an adjunctive treatment for epilepsy in dogs.

Although further scientific, peer‑reviewed literature is needed, when used as an adjunctive to conventional therapy, acupuncture may provide a safer alternative to other unlicensed treatments.

Summary

Recurrent seizures secondary to idiopathic epilepsy is a common presentation in first opinion practice. It can affect all breeds of dogs, with the typical age range being between six months and six years.

Epileptic seizures arise from abnormal neuronal activity within the brain, leading to transient paroxysmal changes in neurological state and behaviour. This manifests in an array of presentations and postures.

Idiopathic epilepsy is a diagnosis of exclusion, based on investigations ruling out extracranial and intracranial causes of seizures. Seizures should be described as generalised or focal seizures, based on clinical presentation.

Distinguishing seizures from other paroxysmal events can be challenging, and detailed clinical anamnesis, physical examination and video footage can aid in reaching a more reliable diagnosis.

Despite some developments in alternative treatments for idiopathic epilepsy being proposed, conventional medical treatment remains the most extensively studied and reliable modality in dogs. Antiepileptic medication should be started when seizure frequency, or its severity, impairs the animal’s quality of life.

Owners should be aware of the possible side effects of medication and owner’s compliance should be sought, as well as clear expectations of the treatment objective.