16 Jul 2024

Sustained management of OA

Ross Allan stresses the importance of collaboration when planning to manage this condition in dogs.

Image © Milan / Adobe Stock.

Contextualised care is nothing new; it has been delivered daily in general practice since “special interests” appeared with the launch of the BSAVA and similar groups in the 1950s and before.

Practitioners long recognised that pigeon-holing specific treatments into the same box as their diagnostics and diagnosis works for neither owners or patients.

The “art of general practice” instead centres around appreciation of the evidence available, interactions with owners, and our own personal experiences, before – in collaboration with owners – making the decision about what is the most appropriate option for their pet, our patient, at that time.

In recognising and assessing this skill, human health care is ahead of veterinary. Although in veterinary, we often perceive the veterinary evidence base to be small compared to human medicine, in both branches of medicine, a myriad of diagnostic and treatment options often remains, and need for discussion and patient/client participation in decision making.

I would suggest that our profession’s recognition of these skills must catch up with human medicine, and do it fast.

This article outlines how a multimodal management plan for osteoarthritis (OA) can be implemented, with a key focus on the on-boarding and inspiring of owners: the art of general practice. This step underpins effective OA management, but also, I would argue, for all chronic diseases we encounter in our patients – and that is a few.

OA management – aims and objectives

OA affects more than 20 per cent of all dogs older than one year, and is traditionally viewed as a progressive, degenerative condition.

Increasing opinion in human and veterinary clinical research suggests that while the latter description may be largely correct in a pathophysiological respect, this tone is wrong in terms of explaining the therapeutic options and management plan for treating OA patients successfully.

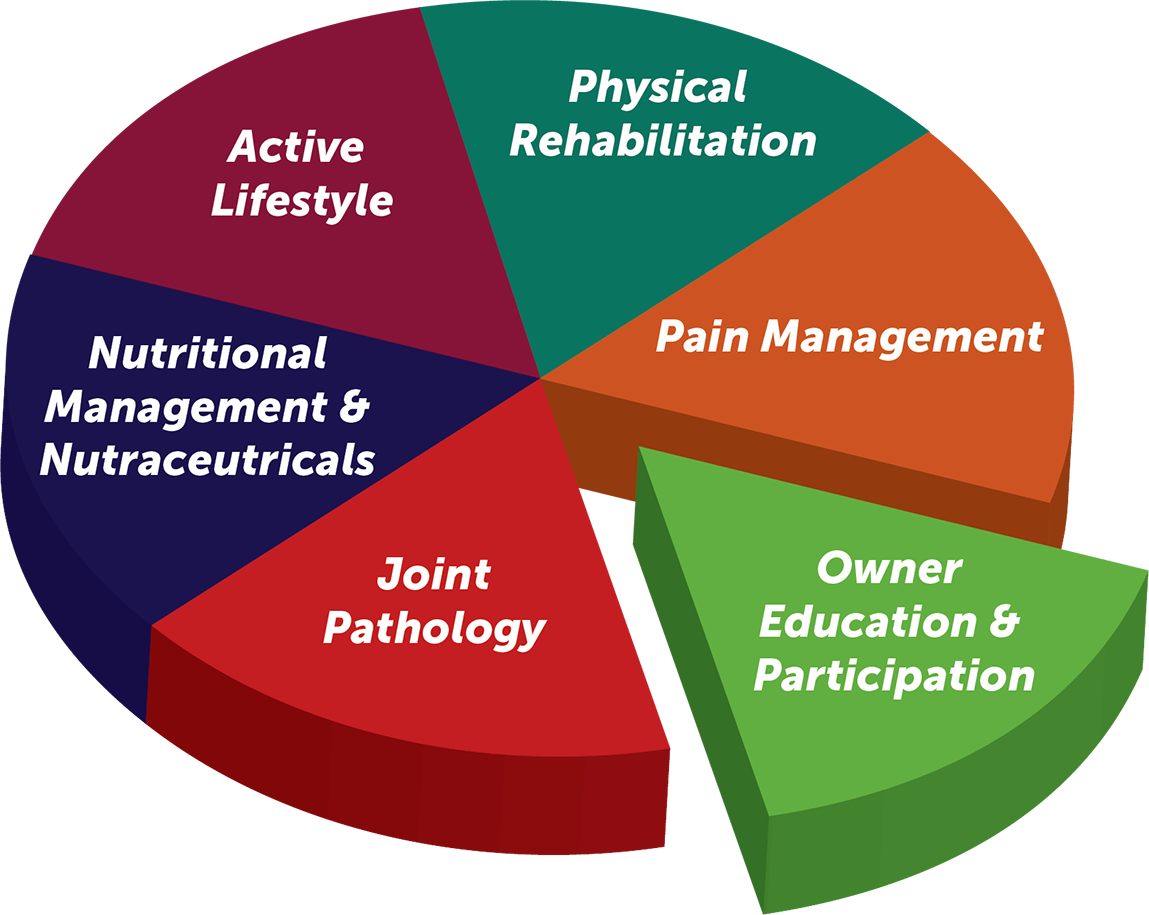

Instead, we need to remember that OA is a dynamic disease and provides scope to improve various elements which can reduce pain and improve function. A multimodal plan (Figure 1) will benefit OA patients, but its successful implementation must be underpinned by purposeful review of progress.

The need for meaningful review is even larger given the commitment often shown by owners, financially and practically. These client “costs” are significant, which increases the responsibility on the veterinary profession – individually and collectively – to ensure the treatment we recommend is effective.

For review, define the objectives you are aiming to target in your OA patient, such as improvement in lameness, comfort, demeanour and “happiness”. Validated questionnaires and other resources are readily available (LOAD, CBPI, COAST and so forth) to improve the reliability of these assessments, while providing a means to review response and visualise the effectiveness of your OA management plan.

Multimodal plans should strive to meet pre-determined objectives and can be developed from a standardised “outline” template. They should, however, involve and include the pet owners themselves, and reflect the skills of clinical team who are collaborating to deliver care.

So, when developing multimodal plans, be clear to ourselves and our clinical team, as well as owners, what the objectives are, and reassess progress as the OA management plan evolves.

Team management of OA

Chronic disease provides an opportunity for team collaboration and development of care pathways. Many practices will already have some formats and nurse clinics in place.

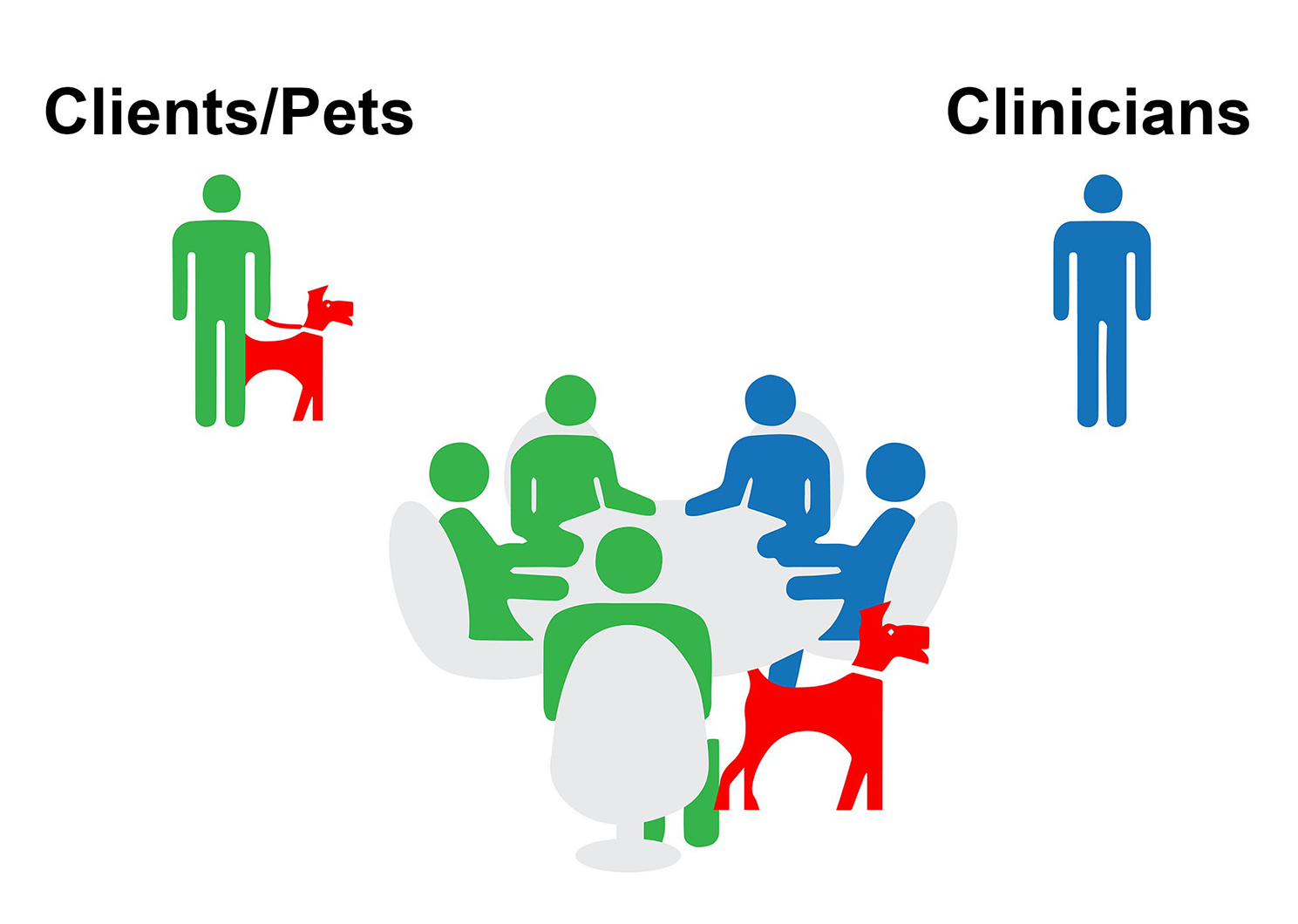

When successfully launched, a realisation came to this author that vets cannot deliver effective OA care entirely on their own. Instead, collaborating with others such as nurses, physiotherapists, hydrotherapists and other members of care teams, will – if successfully planned and structured – improve access, impact and continuity of care. This is a key concept for practices to engage with.

The formation of these “asynchronous clinics” requires training and resources, but the recognition your practice requires these is an opportunity for a step-change in care delivery.

Asynchronous clinics are the format and means to deliver effective, efficient care of OA, and other chronic diseases, in a format which can be more effectively “scaled”, easing pinch points and pressures. This results in improved clinical and job satisfaction for those delivering the care that underpins our profession. Commercial success is the outcome of meeting these key objectives.

What is an effective OA multimodal plan?

Multimodal plans with their various elements can be adapted to assist in OA management.

They address the complexity of the disease and can more easily be modified as the needs of the patient change with time.

OA management should never be viewed as being reliant on a single medical therapeutic. Instead, all plans should address the immediate OA needs, but also look ahead to more long-term management considerations.

When developing your OA management strategy, a number of key components should be considered:

- A multimodal plan based on a template/outline, such as Figure 1.

- “On-board” the pet owner – be optimistic about your patient’s OA.

- Agree a long-term strategy and the way it will be delivered.

- Review and reassess progress relative to objectives.

1. Create a plan – management options with defined objectives

For any clinical problem, it is good practice to identify key issues, which often are multiple, and decide how to deal with them.

One such multimodal framework that can be used can be seen in Figure 1. “Owner education and participation” is highlighted, but each element is important to have in a plan for your OA patients, and has been discussed in previous publications (Allan and Carmichael, 2020).

It is important that when patients are in for review, you review the patient’s progress against the initial objectives before adjusting the OA management plan. This logical step-by-step approach is appreciated by owners and must be shared with them so they fully understand, and can be empowered to contribute to, discussions on possible changes in their pet’s OA management plan.

Failing to review your patient’s progress relative to your predefined aims devalues your care and will lessen an owner’s commitment to the plan you worked together to create.

● Tip: Failure to set objectives increases the likelihood of owner detachment and disappointment.

2. Owner on-boarding

Owner involvement is crucial to success of treating pets with OA, and the process and importance of on-boarding the owner should not be underestimated.

“My black Labrador was six years old when she was diagnosed with arthritis following an acute shoulder sprain. I was stunned. My healthy, energetic dog was now facing a painful, chronic and degenerative disease that would be with her for the rest of her life.” (“Caring for a dog with osteoarthritis,” 2018)

While perhaps not entirely incorrect, this depressing and unhelpful interpretation of OA is a poor starting point for our OA patients. It is, however, all too often the impression of OA that owners get following their pet’s diagnosis.

This is a failure of us as clinicians to emphasise the dynamic nature of OA, and a failure to use the “magic moment” that presents at the time of diagnosis to carefully deliver a message that provides a platform for effective, ongoing client and patient management.

We would not suggest this is deliberate; it fits with the traditional “diagnosis and treatment” approach that underpins our teaching as veterinary professionals. The priorities that require consideration when managing chronic disease, and the owners whose pets have it are, however, different and must be taken into account when discussing chronic disease management.

● Tip: “OA is a progressive degenerative condition” – this tone is too downbeat and nihilistic, so avoid.

Instead, a key element of the OA “day zero” message should be optimism that, for most OA patients, simple medical and non-medical/lifestyle treatments can help. This contrasts with a, “Here’s the painkillers, now off you go”, message.

Emphasising that treatment is not all dependent on medicines; the dynamic nature of OA, and importance of proactively assessing the response to treatment, is an absolutely vital part of successfully treating each and every pet with OA.

When clients are given the opportunity to “learn” the dynamic nature of OA and given a structure that facilitates this inquisitiveness, they will grasp the opportunity to manage their own pets’ OA alongside the clinical team, not separate from it.

This is the “epiphany” that the clinical team (not just vets) needs to strive for: clients not only wishing, but actively demanding, to see their pet’s progress and look for the rational, evidence-based management advice to support their pet’s chronic disease management.

3. Participatory medicine

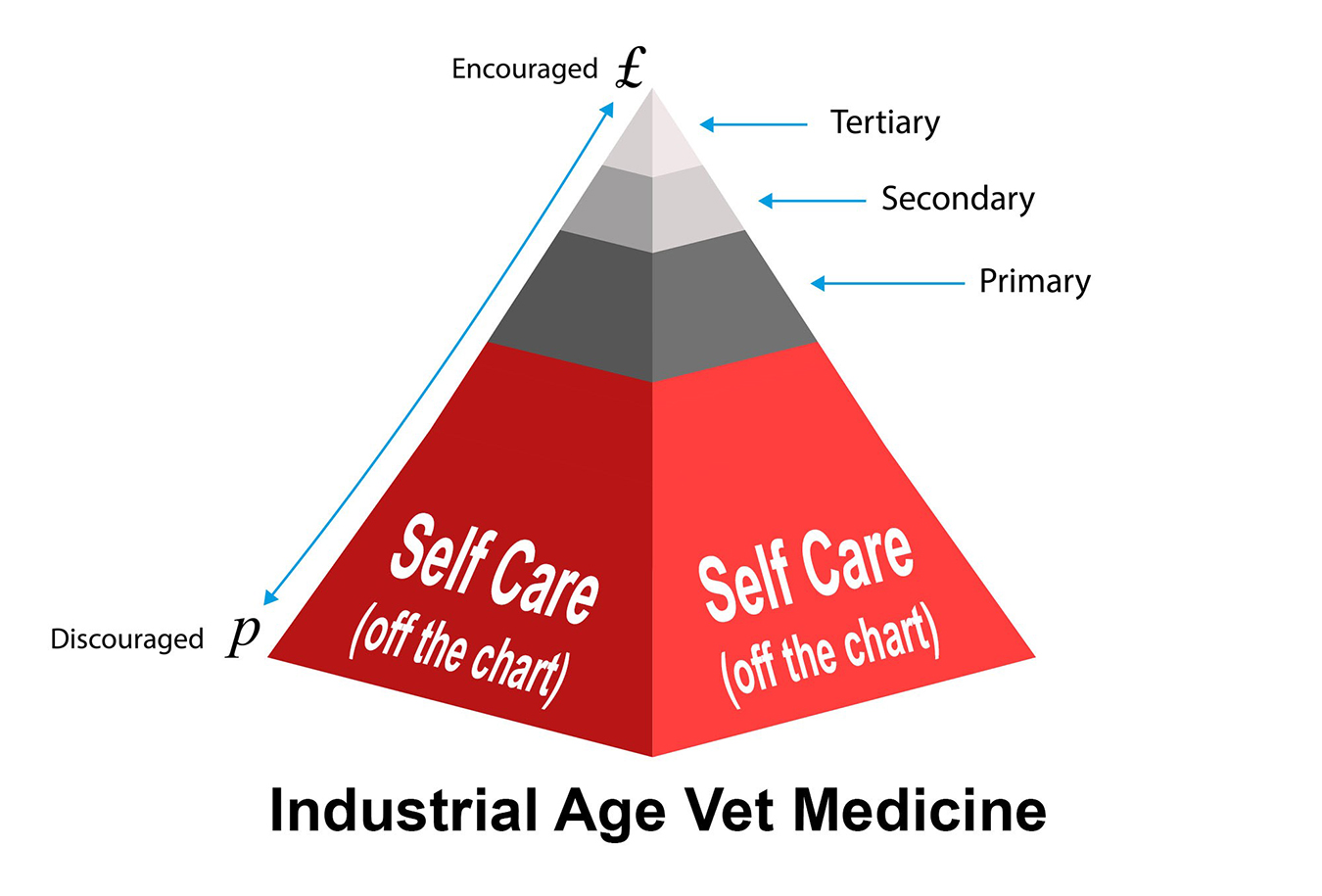

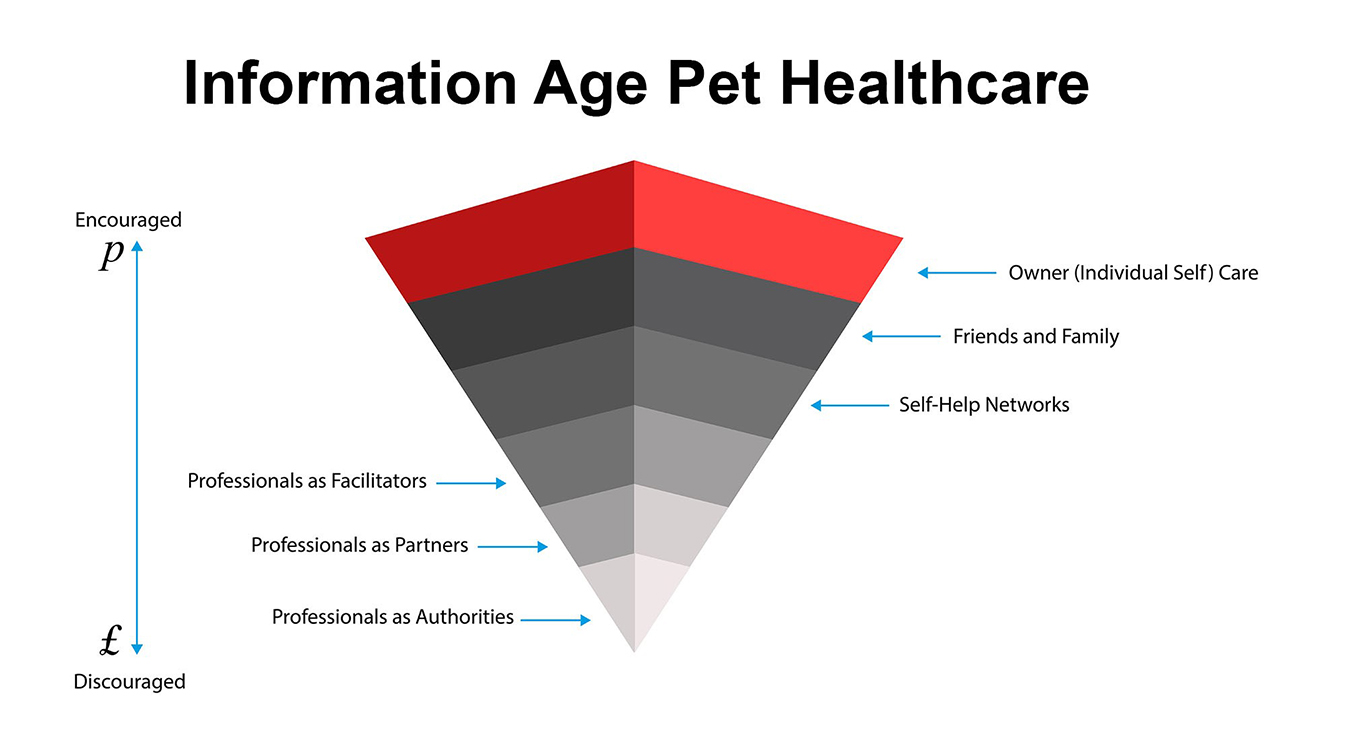

In human medicine, an increasing understanding exists of the importance of the participatory medicine concept, redefining the context in which medical care – especially for chronic conditions is delivered. Patients (or pet owners) are placed at the centre of the decision making: the person who professionals want to help empower to deliver their own care over time (Figure 2).

other as full partners in their pet’s OA journey.

Many of us who manage OA patients are increasingly aware of the value of empowering owners to have OA knowledge, understanding and the confidence to contribute to the discussion on their pet’s care. We want owners to work with us, not only do as we ask – this is undoubtedly a key element to put time into understanding more and is a theme that will doubtlessly develop more in veterinary medicine in the years ahead (Figures 3 and 4).

4. How is your patient’s OA management plan delivered?

Clear identification of the exact plan, as well as addressing any initial concerns noted by the owner at the outset, is critical to this process.

Doing this, and being mindful of the part the owner will play in achieving the first set of objectives, is a key part of successful OA management.

5. Review

At review, follow a repeatable format:

- Review current status relative to the pre-planned objectives.

- Use clinical metrology instrument measurement tools and record results – how do these compare to previous visits?

- Share and discuss results with owners.

- Collaborate with the clinical team to review and deliver specific management interventions.

- Revise objectives and update management plan in light of your review.

- Establish review dates as a key part of the ongoing management strategy.

This approach is very different from waiting for the owner to return an affected dog because its OA symptoms are getting worse or more obvious. Instead, proactive review provides an opportunity to tailor your patients’ OA management plan to their individual needs. Depending on your clinic, this care can often be coordinated with visits to see those you collaborate with in care delivery, such as physiotherapists, hydrotherapists or RVNs.

Summary

A lifetime chronic disease such as OA needs a management plan, owner participation and proactive review, the best way to understand clinical progress and inform and update management. These steps, along with the use of asynchronous clinics, enable collaborative care to be delivered in a clinically beneficial way for patients, rewarding for owners and the clinical team, and a structure that provides a template for how the management of many other chronic diseases can be improved.