28 Feb 2019

Ian Wright discusses the principles of controlling these parasites and the vital role VNs play in making recommendations for individual pets.

Fleas and ticks are common ectoparasite of household pets, and a source of revulsion, distress and irritation to owners. They can also transmit disease to humans and pets.

Control of these parasites on pets and in households is, therefore, vital, and requires accurate and consistent parasite control advice to clients across the whole practice team. Nurses play a vital role in assessing the parasite risk to individual pets and then tailoring control advice to their needs.

This article discusses the principles of flea and tick control, and advice for individual pets.

Routine parasite control forms a vital part of pet health programmes, with some parasites requiring year-round preventive treatment in all pets, and others requiring a risk assessment based on geographical and lifestyle factors.

Fleas are considered to be highly prevalent on domestic cats and dogs, and present across the UK, with as many as 1 in 5 cats and 1 in 10 dogs having fleas at any one time.

Tick-borne disease also represents an ongoing and growing risk to UK dogs and their owners. This comes from both increasing numbers and activity of endemic ticks, and exotic species introduced through travelled and imported pets.

Clients may approach veterinary practices for flea and tick prevention advice because of existing infestations or for routine prevention. In either case, advice should be accurately based on the latest evidence and consistently given across the whole practice team.

Nurses play a vital role in assessing the parasite risk to individual pets and then tailoring control advice to their needs.

The fundamental difference between pet infestations with fleas and ticks endemic in the UK is flea populations establish in homes, whereas ticks are mostly encountered outdoors.

Adult fleas lay eggs within 24 hours and can lay 40 to 50 eggs per day. The eggs hatch in 1 to 6 days and the larvae can then pupate in as little as 10 to 20 days under warm, humid conditions. Adult fleas can then emerge from the pupae in three weeks.

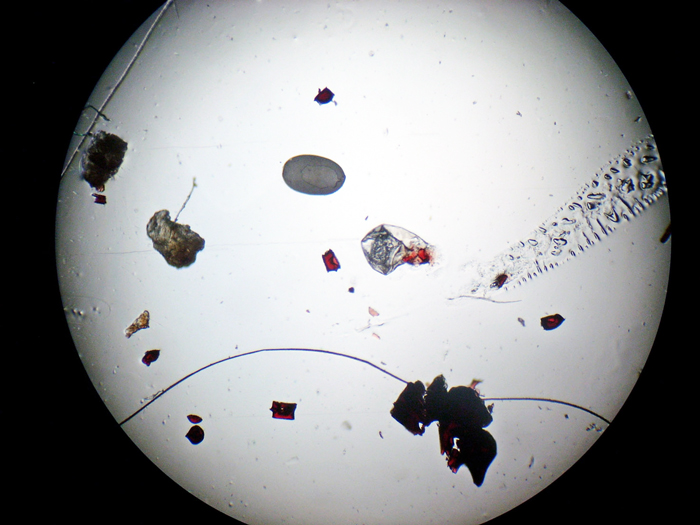

Under most household conditions, the life cycle can be completed in less than eight weeks. The speed of reproduction means infestation with just a few fleas can lead to heavy environmental contamination of homes and, at any one time, 95% of the flea problem exists in the home as eggs (Figure 1), larvae and pupae.

Although adults can emerge from the pupae within a few weeks, if conditions are unfavourable, pupae can remain viable for one to two years. This means infestation can be established, even if mammalian hosts have been absent for some time.

The most common ticks found on UK dogs continue to be Ixodes species – the vectors of Lyme disease (Abdullah et al, 2016; Wright et al, 2018). Dermacentor reticulatus also present in the UK, with the continued presence of foci in Wales, and south-west and south-east England. These foci present an opportunity for Babesia canis to establish – as occurred in Harlow, Essex, in 2015 (Phipps et al, 2016).

Ixodes and Dermacentor species have four life stages: egg, larva, nymph and adult. They require three hosts to complete their life cycle. Ticks must take a blood meal to moult to the next life stage and produce eggs.

The whole life cycle is typically completed within three years, with larvae feeding on small birds and mammals, and nymphs and adults feeding on a variety of mammals, including dogs, cats and humans.

This life cycle prevents ticks from establishing populations in UK homes. The exception is the exotic tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus, which, if introduced to homes via travelled pets, can complete its life cycle in three months and infest homes in a similar manner to fleas (Hansford et al, 2015).

Although cat fleas cannot live and reproduce on people, they can bite, leading to human irritation. They are a cause of flea allergic dermatitis and vectors for a variety of infections, including Bartonella henselae (the cause of cat scratch disease), Rickettsia felis (a cause of spotted fever), haemoplasmas (the cause of feline infectious anaemia) and Dipylidium caninum tapeworms.

Ticks are also very competent vectors of disease-causing pathogens – 2.37% of Ixodes ticks on dogs have been shown to carry Borrelia species, which cause Lyme disease (Abdullah et al, 2016).

D reticulatus is capable of transmitting B canis, which can be highly pathogenic to dogs. A focus of B canis infection was confirmed in Harlow, with cases in untravelled dogs from Harlow; Romford, East London; and Ware, Hertfordshire.

R sanguineus on travelled pets is capable of transmitting numerous pathogens, including Ehrlichia canis and zoonotic Rickettsia species, making household infestations a significant zoonotic disease risk. Both ticks and fleas can also cause anaemia, if present in large numbers, and are a source of revulsion, eroding the human-animal bond.

All cats and dogs may be exposed to fleas, leading to the establishment of household infestation. Even indoor cats may be exposed if adult emergence from pupae are triggered by pets or owners outside, leading to newly emerged adults entering into households.

Use of a routine effective flea adulticide is, therefore, crucial on cats and dogs all year round. Environmental treatment is also useful in bringing existing household infestations under control.

Adult fleas can lay eggs within 24 hours, so the adulticide chosen must kill fleas at least within that time. They must also be administered frequently enough to continue to prevent flea egg laying.

The time after application of the adulticide at which fleas survive long enough to lay eggs is known as the “reproductive break point”. If the reproductive break point is reached, flea control will fail. Frequent swimming or shampooing may affect the efficacy and duration of action of imidacloprid and fipronil spot-on solutions, so this should be considered when choosing a specific product.

Environmental treatment to reduce eggs, larvae and pupae will decrease the time required to bring an infestation under control. Aerosol sprays containing an insecticide and insect growth inhibitor used in household environments are useful to reduce flea and larval numbers, while also preventing development into pupae.

When using aerosol sprays, all areas where pets have access – such as cars, furniture and bedding – must be treated. Removal of obstructing objects – such as children’s car seats, pillows and cushions – will aid aerosol penetration. These should also then be treated separately. Care must be taken to follow instructions – and remove fish, birds, invertebrate pets and cats – while treatment is taking place.

Systemically acting products containing lufenuron can be used in pets to prevent flea eggs from hatching. Some adulticides, such as imidacloprid and selamectin, are shed into the environment after the pets have been treated, reducing environmental egg and larval contamination. Some spot-on flea products also contain the growth regulator S-methoprene to achieve a similar effect.

Daily vacuuming of areas frequented by flea-infested pets has also been demonstrated to reduce pupae numbers in the environment, as has hot washing of pet bedding to at least 60°C.

The risk of exposure to ticks in the UK has increased – with a milder climate allowing feeding throughout much of the year, in addition to seasonal peaks in spring, summer and autumn (Abdullah et al, 2016; Wright et al, 2018).

Some pets will be at considerably higher risk of exposure based on lifestyle; therefore, a risk assessment should be made to establish if tick prevention is required in an individual pet.

Several factors should be considered:

Use of drugs that rapidly kill, such as isoxazolines, or repels and kills, such as pyrethroids, will greatly reduce tick-borne pathogen transmission. Only licensed treatments with safety and efficacy profiles in the target species should be used.

Checking for ticks at least every 24 hours is essential in high-risk pets and those that have travelled abroad, as no tick preventive product is 100% effective and the challenge in some geographical foci can be very high.

Ticks should be removed with a tick removal device (Figure 2) or fine-pointed tweezers (Figure 3). If tweezers are used, the tick should be removed with a smooth upward pulling action. If a tick hook is used then a simple “twist and pull” action is employed.

It is important owners are instructed how to remove ticks without stressing them, or leaving the head and mouthparts in situ. Compressing or crushing ticks in situ with blunt tweezers or fingers will stress the tick, leading to regurgitation and emptying of the salivary glands, potentially leading to increased disease transmission.

Traditional techniques to loosen the tick – such as the application of petroleum jellies, freezing or burning – will also increase this likelihood and are contraindicated. Also, a limited window of opportunity exists with most cats to remove ticks, so delay caused by product application should be avoided.

Veterinary nurses have a vital role to play in delivering practical and effective flea and tick control advice to clients. Pet owners often perceive nurses to be more approachable than vets, with less constraints on their time (Tottey, 2015).

Clients seeking a recommendation from vet practices regarding flea and tick control must be given advice that is accurate and consistent, so messages given to clients are clear and effective.

Clients may seek advice because they have already seen fleas or ticks on their pet, have a known existing flea infestation or because they want effective routine prevention as part of an overall parasite control programme.

In the case of existing flea infestations, it is important owners understand heavy infestations of fleas will take at least three months to eliminate – even when environmental treatment is used (Dryden et al, 2000). If this is not effectively communicated to clients, they may become disillusioned with the product used and, therefore, compliance may be reduced.

It is also important to emphasise, even when preventive products are used, lifestyle may lead to re-exposure to fleas and ticks, and subsequent observation of parasites on the pet does not necessarily indicate treatment failure.

Even the most effective tick product is not 100% effective, and all flea and tick products do not kill instantly. Stressing, however, that using an effective product frequently enough will greatly reduce pathogen transmission and prevent flea household infestation will help maintain compliance if ticks and fleas are seen.

Different clients will respond to different communication tools and a combination of approaches is often helpful, including:

Checking pets for fleas and ticks is essential before initiation of parasite control and at regular intervals after a plan is in place. This establishes whether exposure is taking place, a flea infestation is already present and ongoing flea control is being effective.

A full clinical examination should be performed and the pet thoroughly checked for ticks, concentrating on the head, face, legs and ventrum (Wright et al, 2018). If any clinical abnormalities are detected, the patient should be referred to a vet.

The pet should also be checked for fleas using a flea comb. Fleas and flea dirt may be present (Figure 4). The coat should be combed or brushed on to damp cotton wool. Flea dirt will run blood red in contact with water.

Product choice is the key to effective control and owner compliance. By involving the client in the decision-making process, the VN can tailor the control plan to the client’s preferences and pet’s lifestyle.

A number of points should be discussed with the client when choosing a product and putting a control programme in place:

The veterinary nursing team in practice has an essential role to play in the formulation and implementation of flea and tick control plans. Through education of clients on the life cycles of fleas and ticks, and the risks they pose to both pets and humans, compliance can be increased.

The parasite control needs of pets will differ, as will the products best suited to the individual pet’s needs. By working in partnership with clients, mutual and informed decisions can be reached that will improve pet health, decrease zoonotic risk and strengthen the client-practice bond.