27 May 2025

Stuart Carmichael BVMS, MVM, DSAO, FRCVS and Ross Allan BVMS, PGCertSAS, MRCVS explain why a united approach to managing osteoarthritis in pets can benefit all of those involved.

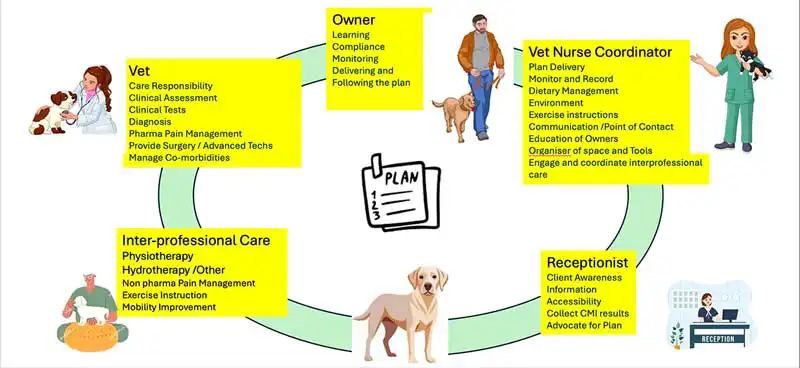

Figure 1. Collaborative care delivers multiple skills from Team OA to meet the wide care demands of the chronic OA patient. Image: evannovostro / Adobe Stock

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a much more complicated disease than we once thought. It develops over time to involve all the structures of a joint and drives changes in both the neurological system, affecting pain perception, and in the muscles and soft tissues adjacent to affected joints, compromising stability and function.

This results in a wide range of pathological combinations developing over time and presenting a variety of challenges for management. There is no such thing as a standard OA joint.

It is fair to say that OA is clinically defined by pain, and indeed the most common response after diagnosis is prescribed analgesics to block the pain.

The pain associated with the disease is complex, with combinations of acute, persistent and chronic pain depending on the situation. This is driven by the pathological changes dominating depending on the stage and the current status of the disease.

Management options are varied and can be selected based on the stage of the disease, the joint (or joints) involved and the pain state identified.

Lifestyle variables are also very important, with adiposity and obesity, environmental factors and exercise patterns also key factors to consider.

Yet, most patients identified as having OA are diagnosed presumptively without tests or assessment of stage or confirmation of diagnosis1. They are then treated with a set formula of analgesics in search of the resolution of obvious or presumed clinical pain.

Is this the best we can do?

What do we mean by collaborative care? Essentially, it is various health care professionals working together and tailoring treatment plans according to the needs of individual patients in human health care (Figure 1).

In our situation, this incorporates contextualised care, meeting the needs of both the patient and owner/family to better guarantee good outcomes from management. This places the owner central to the success of this and takes their views and preferences into account. It also addresses the varying demands of a disease that alters over time and requires progressive, consistent and sustained care.

The Veterinary Osteoarthritis Alliance (VOA) has a dedicated group working on practical delivery of this type of care and promotes the concept of “Team OA”, with the whole practice team working with allied mobility professionals and empowering pet owners to improve management using evidence-based care.

This collaborative care model is a challenge to the traditional model previously outlined.

A major challenge in all OA case management is the fact that the disease cannot be cured.

Currently, management practices can best be described as reactive and palliative. OA manifests itself through pain. However, the identification of pain in our pets is far from simple. We now understand the role and impact of chronic pain associated with the disease, and have modified veterinary care to address this by using multimodal analgesic combinations and more prolonged treatment periods.

We understand that if an OA patient has sensitisation or pain-related neuropathology, it takes an extended period of stimulus blocking to both reduce and, in some cases, remove this complication to pain management. We know the impact of chronic pain in OA from human sufferers who can articulate the problems it causes, and we understand that these will commonly be manifested as alterations in behaviour in our patients.

It is very difficult to quantify this type of pain in humans and much more difficult in animals. But is it correct to assume that every dog or cat with OA in a joint suffers from severe chronic pain, and treat them accordingly? We know from human experience that OA joints can often go dormant or pain free for long periods2.

Is this not also likely to be the case in our patients and, if so, are we justified in using constant analgesic treatments just in case?

We must also remember that in what is described as the “joint organ concept” the tissues and fluid inside, around and connected to joints are collectively involved in joint OA pathology and driving pain – these require our attention, too. This dynamic and evolving disease problem is not fully addressed by a system based on presumptive diagnosis, minimal disease assessment, followed by a standard approach to treatment and limited follow up or monitoring.

Contextualised and sustained management of OA does not readily fit into our standard practice model, which depends on short consultations to “screen, treat and cure”.

We can use a sporting analogy to illustrate the problem. Standard veterinary care is like a team preparing for a cup final. During the game, the cup will be won or lost depending on the players on the park, and the result will be immediate. This is akin to the standard veterinary approach where the “players” making a difference are the vets with their array of skills or treatments.

However, chronic OA care is more like a league campaign, where results must be accumulated over time. In this scenario, the key players are not the veterinary team, but the patient and the owner.

The veterinary team and allied professionals must prepare, manage and coach from the sidelines, using diverse skills to keep the team (patient) fit and functional.

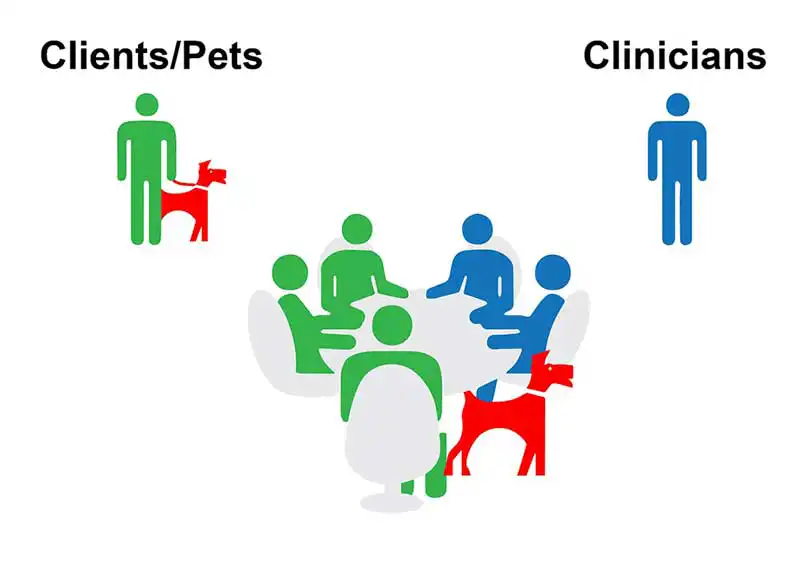

This is “Team OA”, a team that includes the pet owners, vets, nurses, receptionists, physiotherapists, and other allied professionals (Figure 2), working to win the long game that is successful OA care.

Short-term gains are important, but we must also focus on the longer-term goals in every case. We need to target both in OA management.

We are well aware of the high numbers of dogs and cats with pathological OA in the pet population, and so in the practice population.

Recently, a study challenged the perception that OA was an older dog problem, identifying clinical OA in significant numbers in dogs younger than four years3.

Cats are also facing a population OA epidemic. In a recent article, Jackson et al4 identified that weight issues and musculoskeletal problems were the two most common clinical problems in older dogs presenting in practice, outscoring others such as cardiopulmonary, renal and endocrine problems, which currently receive much more veterinary focus.

This illustrates that there is a large proportion of patients with lifelong clinical issues affecting quality of life that are not being currently addressed in practice. We are aware of this, but what determines our threshold to act and our ability to respond?

In recent studies exploring attitudes to management, vets have identified various credible operational barriers, but also have revealed some real limitations created by their approach to OA cases1.

Defending using a presumptive diagnosis, many vets argued that using tests such as x-rays for confirming diagnosis would not usually alter management decisions. Cases were “diagnosed” by recognising the “typical OA case” based on history and examination1. Such an approach will miss early cases, younger dogs and patients with more subtle or atypical presentations.

The paper by Belshaw et al1 also found that, for many clinicians, the final piece of evidence required to confirm a diagnosis of OA was response to treatment, typically with an NSAID for a 5 to 14-day period. We would suggest this to be inadequate evidence at best.

Another finding was the suggestion of an unspoken “mutual frustration” from these simplistic diagnostic procedures. They do not work well for either clinicians or owners, the latter often not readily accepting both this approach and the recommendations that derive from it.

Time pressures are often cited as the main driver for this from clinicians, but it does imply that OA is not regarded as a major problem.

Pet owners are often held up as a barrier to providing care. However, for true collaborative care they are a key part of the team, delivering successful management.

Recent studies have highlighted the pet owner’s dilemma when presented with a presumptive diagnosis and a course of treatment with little information about the disease or the objectives for treatment. Most owners do understand OA, contrary to what vets often think, and may have certain prejudices and beliefs that need to be addressed to create compliance with management suggestions1.

The fact that OA is often an additional diagnosis when attending for another reason, and is not highlighted as a major issue, can make it difficult for owners to commit time or effort required to improve their pets’ condition.

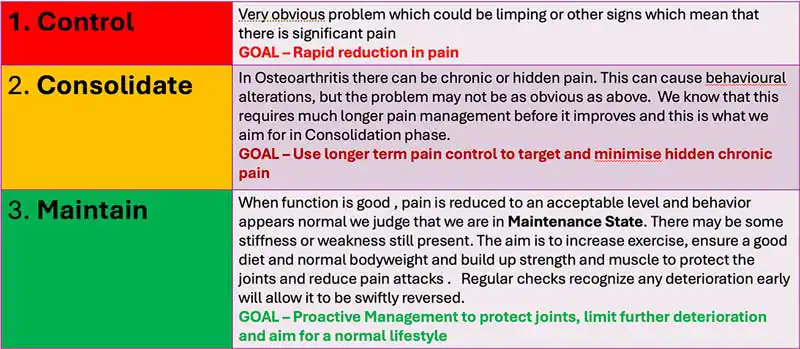

In a previous article for Vet Times5, Allan outlined an approach to introduce multimodal plans and emphasised the need to spend time on-boarding clients (Figure 3). He stressed that an optimistic approach, explaining that OA is a dynamic disease, that there were many options for managing it successfully, and that the aim was to ensure a good quality of life was important to get the owners engaged as part of the team OA concept.

There are benefits to the owner as well as the dog in engaging with a positive and successful management plan, as owners themselves experience considerable negative impacts caring for a pet with OA6 .

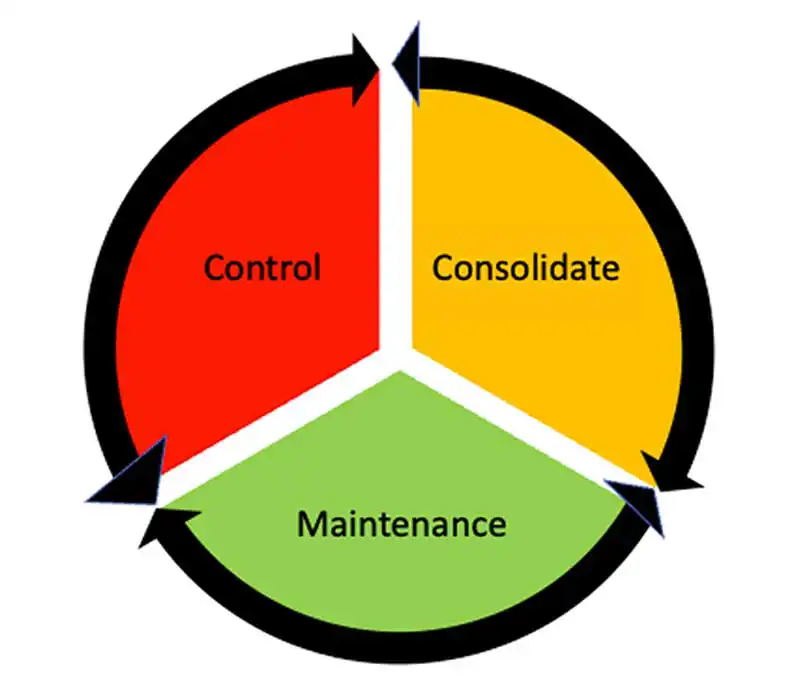

One simple method to help explain the approach to treatment is to use the control, consolidate, maintain (CCM) approach. This states that the pet will always be in one of these three clinical states (Figure 4), each of which requires a different approach to management. These dynamic states can, however, continually interchange during the full course of the disease (Figure 5). The key objective is to work to place patients in the maintenance phase and quickly recognise if they depart from this and correct it. The CCM approach helps explain management aims and shows that there is a clear plan to control the disease. This is very easy to understand, helps succinctly clarify management objectives and, importantly, identifies the need for constant ongoing management. Owners need information and education about their pet’s OA. It provides a platform to enable them to better understand the discussion of their pet’s management strategies and options. The clinical team should also understand and accommodate owner preferences, and provide ongoing information and support. This completes the package.

Current practice is not perfectly suited to the delivery of sustained chronic care. Barriers identified by vets include pressure on time, space, client resistance and compliance. Skill shortage and training were also cited.

The VOA believes that one of the answers to this involves accepting it and taking a much more structured approach to delivering the care that OA patients and their owners require. The VOA has been working on a model for in-practice mobility or arthritis clinics (Vet-IMPACT), with guidelines, training and tools that practices can use to get started (Vet-IMPACT Toolbox). This has been developed following experience from practice studies focusing on mobility care7.

The model requires dedicated clinics where adequate time, space and resource are committed to dealing with cases with mobility problems and OA. It is suggested that these clinics can be nurse coordinated, with trained VNs providing the focus point for communication, care, contact and integrating vet and other inter-professional input. They will also be responsible for recording management and outcomes over time. Each patient should have a bespoke management plan, detailing the targets and management agreed with the pet owner, which will evolve through time. This is a functioning Team OA which can overcome the operational blocks that prevent practices delivering chronic disease care and developing true collaborative care.

This article has promoted the benefits of collaborative care in managing OA as a chronic disease, with clear roles for vets, nurses and reception staff in a mobility clinic model. It has also focused on the importance of an informed and included pet owner.

Introducing extended inter-professional care by using physiotherapists, hydrotherapists and other allied mobility-linked professionals will add a new dimension to chronic care.

At present, there is poor utilisation of this resource, with a recent study identifying that only a small proportion of cases were directed to use these (18 per cent), while most cases under care were just using pharmaceutical management (82 per cent)8.

When this care is accessed, it is often by referral transfer, and there is no integration or attempt to work towards a planned common purpose. This is essential if the best use is going to be made of this resource.

A shared management plan is key, with clear objectives and targets fulfilled by different members of the extended Team OA.

Coordination and recording are essential, as described, to bring together an effective collaborative care model.

Collaborative care is a different method of approaching OA management.

If used correctly, it can move management to a new plane9 and provide answers to sustaining care in patients.

However, it must be well planned, share common management goals, have outcomes recorded and be well coordinated.

In-practice mobility clinics are one way of providing a basic structure to achieve this.