2 Dec 2025

Toxicology – preparing for cases and prevention work with owners

Nicola Robinson BSc, MA, VetMB, MRCVS considers how professionals can help owners to prevent potential poisonings, and explains why it is crucial to treat the patient, not the poison.

Lilium species.

This article will provide guidance on what vets should be aware of before poisoning cases present, so that they are ready to tackle them to the best of their abilities.

This will ensure that patients receive the most appropriate treatments, common pitfalls are avoided and there is the highest chance of a successful outcome – both in terms of the pet’s health and the owner’s perception about how the case was handled.

Be prepared that treatment may not be needed

Carrying out a risk assessment on each individual case is essential before treatment starts to decide whether it is needed.

If the patient is asymptomatic or only showing mild signs, there is time to do this, and it is important to not have a blanket protocol for all animals presenting with poisoning. The key is not to start treatment until you know that it is indicated – particularly in cases where the effects from the toxin are likely to be milder than the treatment you are planning, which may be invasive and unpleasant for the patient.

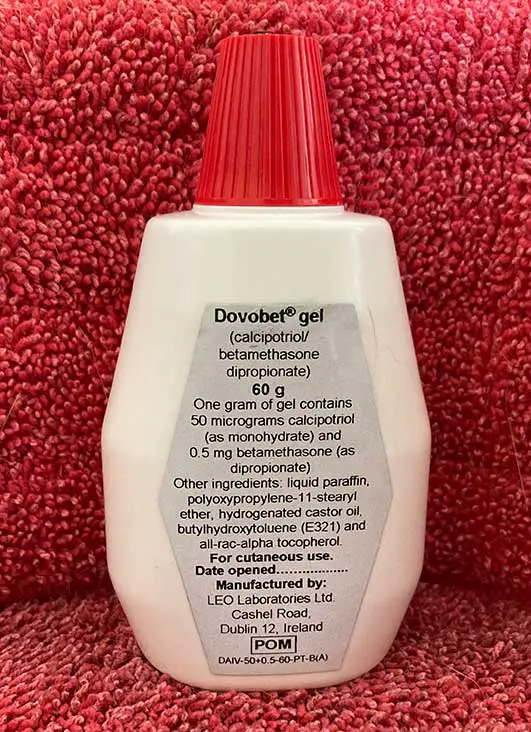

The risk assessment involves working out exactly what the animal has been exposed to and by which route. The active ingredient needs to be established, as well as the strength (if applicable) and amount. This involves careful questioning of the owner and asking them to bring in any packaging, if possible. Sometimes, the active ingredient is not an issue, but an excipient is toxic, so looking at the full ingredient list of a product is important.

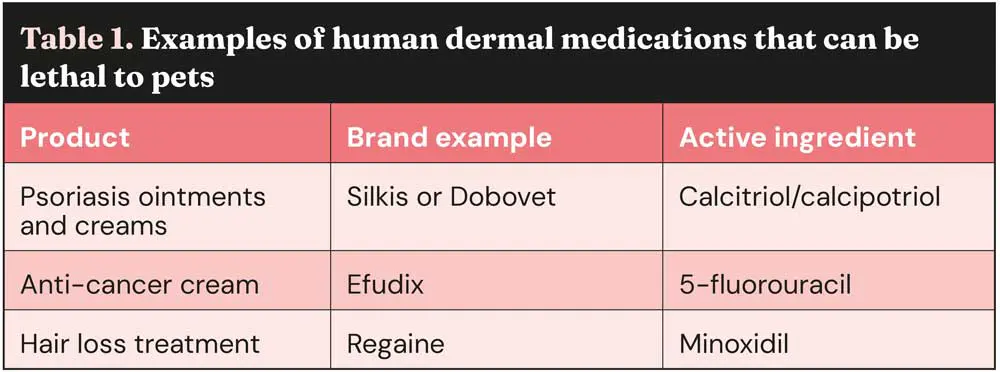

Quantity alone is not always an indicator to treat – it is the toxic dose that is important. There are some medications where a significant number of tablets can be ingested with little effect and no treatment is needed, while others are extremely toxic at very low doses. Some dermal medications are particularly toxic and can cause serious clinical signs or fatalities at very low doses; for examples, see Table 1.

Be prepared to make an individual treatment plan

Vets often know how to treat the common toxins, but treatment plans should be tailored to the individual case – so, remember to treat the patient, not the poison.

It is important to have a specific plan in place for the patient, taking into consideration all the necessary factors. Treatment protocols will vary in complexity depending on the species of animal affected (some toxins affect species differently; for example, xylitol in dogs or Lilium species in cats), route of exposure, amount/dose, patient’s weight, time after exposure, clinical signs and any pre-existing conditions.

Time since exposure is particularly important, since toxins are absorbed at different rates. Inducing emesis after one hour is too late for some agents (such as salt, xylitol and naproxen) and, therefore, not worthwhile. However, some substances remain in the gut for a prolonged period, such as raisins and sultanas; therefore, later emesis may be worthwhile.

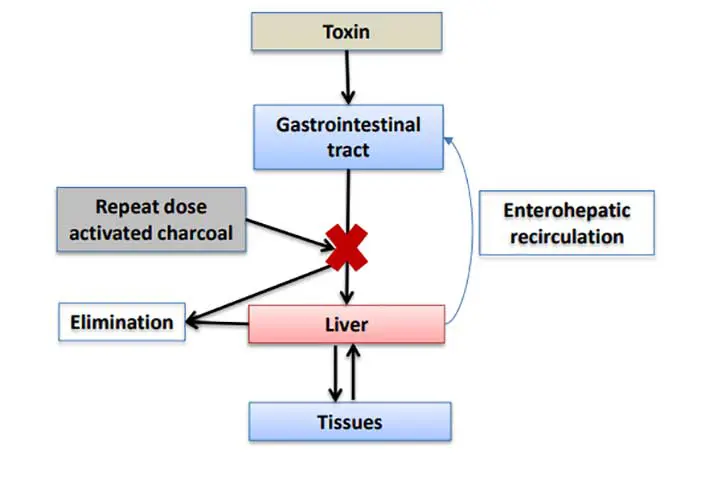

A single dose of activated charcoal is appropriate for most poisoning cases, but the charcoal needs to be in contact with the ingested substance, and so should be given as soon after ingestion as possible. For toxins that undergo enterohepatic recirculation, the window for repeated doses of activated charcoal is longer (approximately 24 hours), but if this has passed, then it is not worth giving any because it will be ineffective. There are other cases when emesis should definitely not be induced.

A few examples of these include:

- Using apomorphine after ingestion of a medicine that causes sedation, as apomorphine will exacerbate sedative effects.

- After ingestion of an oral anticoagulant that is rapidly absorbed, since vomiting can provoke bleeding.

- After exposure to a toxin that causes fast onset seizures.

- After ingestion of any toxin that is caustic, corrosive, acidic or alkaline (such as drain cleaners or cement).

- After ingestion of a substance that is volatile (such as petroleum distillates, as they can be aspirated, causing chemical pneumonitis).

- After ingestion of a detergent, since these may cause foamy vomitus which can be aspirated, causing pneumonia.

Initial thoughts about a toxic exposure may not be correct; for example, thinking that if a dog has eaten rat poison, it must be an anticoagulant and it needs gut decontamination and vitamin K, when there are actually eight different anticoagulants, each with its own toxic dose, so treatment may not be required, even with large ingestions. Added to this, there are other types of rodenticides to consider, notably vitamin D, which can cause hypercalcaemia and, if not treated appropriately from the start, irreversible calcification of the tissues.

The treatment plan would, therefore, be completely different from an anticoagulant rodenticide.

Be prepared for what the treatment could involve

Treatment plans can vary from giving one dose of activated charcoal in some cases, to long periods of intensive nursing and monitoring for others. The latter may mean that referral to an OOH provider is required, with financial implications for the owner.

Consulting a veterinary poison centre in these instances can help tailor the plan according to the progression of the signs and the individual circumstances of the owner, advising what the impact on the prognosis is depending on which route is taken.

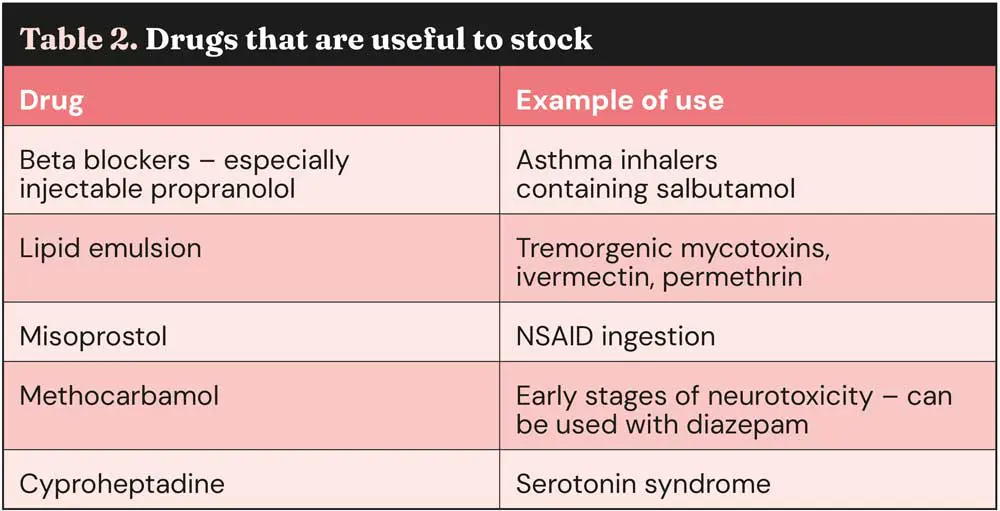

Some medications are very useful in poisoning cases and are regularly recommended, but they are often not in stock (Table 2).

Understand the pivotal role of poison centres

Many owners do not appreciate that toxicology is a specialist area of veterinary medicine and often think that vets should know how to treat all poisons without understanding the need for external support.

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that “poison centres are sources of specialised expertise to address the fact that health professionals could not be expected to know about the toxicity of every chemical substance and product, and also to provide a focus for toxicological research” (WHO, 2020). This is equally true for veterinary and human poison centres.

In addition to providing advice on case management, poison centres play a crucial role in toxicovigilance and research. They continuously collect and analyse case data and trends, identify new risks, and gather information on the toxicology of pharmaceuticals and other agents, including any new products that come to the market.

Case follow-up information is essential for refining treatment advice and understanding toxic doses, onset, duration of clinical signs, and outcomes. Vets are encouraged to report poisoning cases to poison centres to contribute to this data collection. A case or two involving a specific substance in a single veterinary hospital may not raise suspicion, but several cases reported to a poison centre may act as a signal for a larger issue.

There are very few specific veterinary poisons centres in the world, located in the UK, France, US and Australia. The Veterinary Poisons Information Service (VPIS) was launched in 1992, amassing almost 400,000 cases on its database since then and handling more than 25,000 cases per year.

Many online sources contain misleading, conflicting, wrong, potentially dangerous or outdated treatment recommendations and advice on poisoning. Poison centres are a specialist resource for vets and pet owners, providing accurate, up to date and tailored advice.

Poisoning advice in the UK

In the UK, there are two services for poisoning advice: Animal PoisonLine (APL) for owners and the VPIS for veterinary professionals.

It is worth noting that they are completely different services, and it is important to know how they differ to select the right one at the time of a poisoning case.

For information including fees and contact details, visit the APL (www.animalpoisonline.co.uk) and VPIS (www.vpisglobal.com) websites. Approximately 80 per cent of owners do not need a vet visit after an APL consultation. If an owner does need to go in for treatment, the vet can call the VPIS using their membership for full treatment advice tailored to the individual case, if required. In these cases, the owner is refunded the APL fee.

On the APL line, we do not go through treatment with the owner, since it would not be safe or appropriate to expect them to relay this to the veterinary practice. However, if they need a vet visit, we do inform them why immediate treatment is needed, how serious the case is and try to manage their expectations regarding what will happen at the vets (such as level of treatment); for example, we may say that hospitalisation is or is not required, or that it is too late to make their pet sick, but that there is another treatment to absorb the toxin that the vet can give.

If an owner informs the practice of this advice and the vet wants to just confirm that this is in fact what was discussed, they can call the VPIS line for free. A credit is only charged when full management advice is given, including expected signs, timescales, treatment and prognosis.

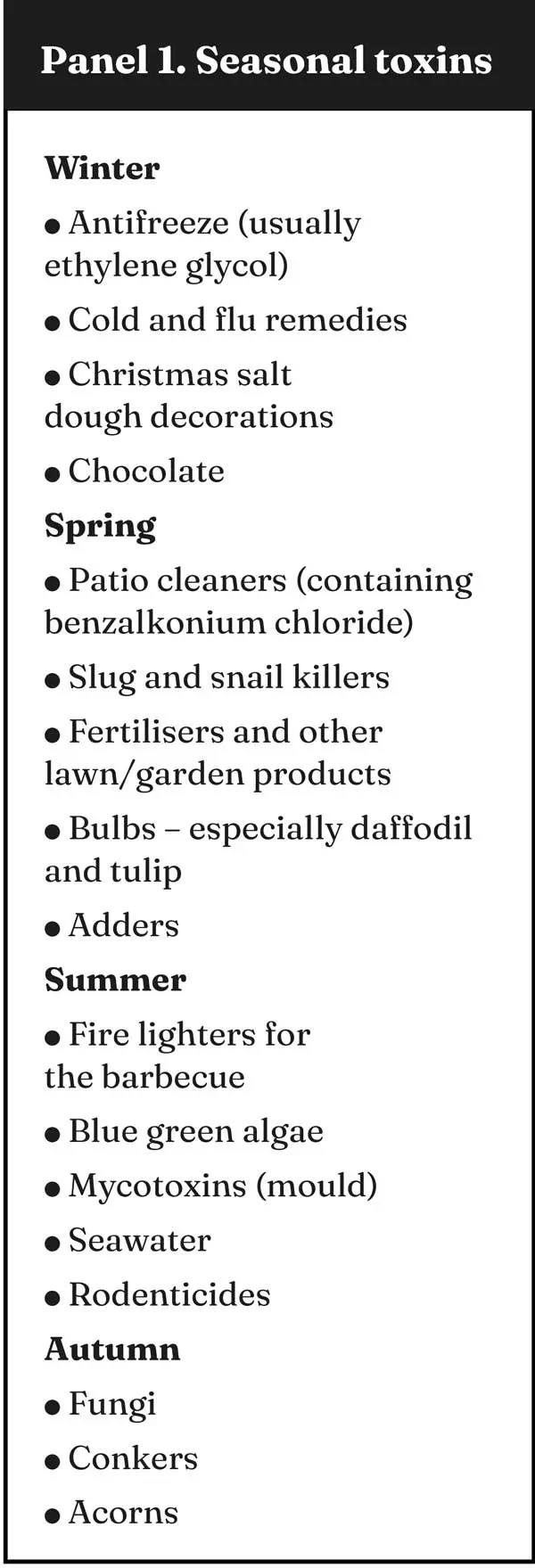

Know about seasonal toxins

It is worth knowing which toxins you are likely to see at different times of the year so that they are top of your list if a patient comes in with specific signs but no witnessed ingestion. See Panel 1 for some common poisons by season.

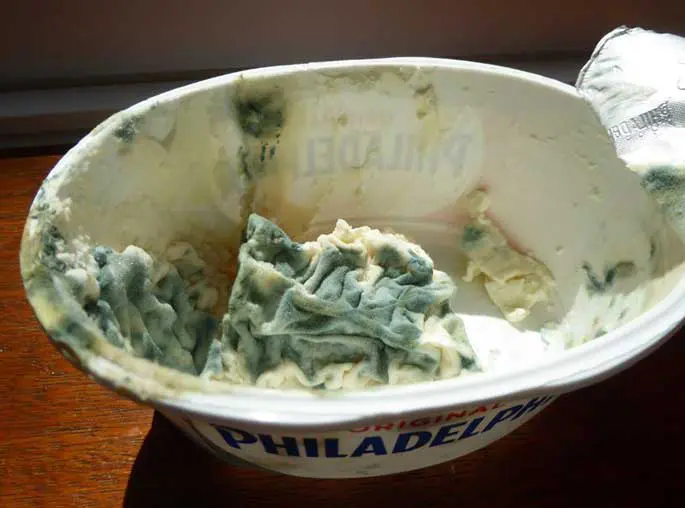

However, the most common agent group the VPIS are called about is drugs, which is not seasonal. The group includes both human and veterinary pharmaceuticals (the most common being ibuprofen, paracetamol and meloxicam), as well as drugs of abuse (mainly cannabis). They represent around 40 per cent of the total call volume.

Be conscious of the user journey

Owners are usually very worried when they think their pet has been poisoned and have nearly always consulted Google before contacting their vet, which does not help. Giving consistent advice is key.

We all want the pet to receive the right treatment from the start, so working together to ensure that we all give the same clear advice will lead to owners feeling reassured about the process.

Tips to ensure a good owner experience

- Do not advise owners to call APL when the pet is very unwell or for treatment advice.

- If you disagree with advice given to owners on the APL line, call us for free to discuss it directly, rather than going against our advice in front of the owner. That way, the owner does not feel in the middle and avoids them, wondering whom to believe.

- If the owner is advised on the APL to go to the vet and we strongly recommend that we would like to discuss the case with their vet, this will be for good reason. Either the case is unusual, with a treatment plan that the vet is unlikely to know, or the case is potentially very serious or fatal. Unfortunately, there are cases where the vet has not called, telling the owner they know how to treat and sending the pet home after an emetic with or without activated charcoal, leaving them at risk by not carrying out other vital treatments and monitoring. Emesis only retrieves 40 per cent to 60 per cent of stomach contents; therefore, although it lowers the risk, it does not negate it – particularly in the case of very toxic agents.

- Seek advice as early as possible and definitely before starting treatment, so that if it is not needed, you can reassure the owner that there is no risk.

- Be aware of toxins that always require veterinary treatment regardless of amount, so that you do not advise owners to call APL for these cases (see the VPIS flowchart).

- Remember that advice is reviewed and updated regularly, so do not rely on a previous similar case to put together a treatment plan. Examples are sugar-free chewing gum, where the xylitol content can change, and toxic doses of any agent, which can change when new research comes to light.

- Consider the amount recharged to owners for a VPIS call. If it is very high, it may put owners off agreeing to a VPIS call and, in turn, result in an inappropriate treatment plan being put in place. Our VPIS membership fees are available on our public website (www.vpisglobal.com).

Advice vets can give to owners to prevent poisoning

- Do not give any treatment at home – especially do not try to make the pet sick using salt water or hydrogen peroxide, both of which can cause more harm than the original toxin (hypernatraemia and haemorrhagic gastritis, respectively).

- Do not give human medications to pets, unless advised by the vet.

- Do not leave open handbags on the floor (as they may contain chocolate, medications, vaping fluid, chewing gum, inhalers, and so forth).

- Replace tops on household, garden or medicine bottles promptly.

- Treat pets like children in respect to access to poisons – store safely and securely, out of sight and out of reach.

- Raise awareness of seasonal toxins.

- Recommend they call APL if the pet is asymptomatic or has mild signs.

- When recommending that a VPIS call is needed, explain why, since the owner may not understand the benefit.

- Advise they keep a close eye on their pets – investigate if something is eaten on a walk and consider indoor cameras for puppies left roaming at home.

- Educate through kittens and puppy packs – the VPIS has informative leaflets that can be sent to any practice to put in their packs.

Remember, VPIS is here to support you

The APL and VPIS lines are open 24 hours a day, all year round, so we are here if a veterinary professional or owner needs us. All our calls are recorded, and we are liable for the information we give you, so we hope our service will help reduce the stress that these cases can cause.

We support veterinary professionals throughout the course of their poisoning case, so that we can work together to get optimal clinical outcomes whenever possible.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 48, Pages 6-10

Nicola Robinson BSc, MA, VetMB, MRCVS, studied zoology at the University of Bristol, followed by veterinary science at the University of Cambridge, and worked as a vet in companion animal and equine practice for 16 years. In 2015, she joined the Veterinary Poisons Information Service (VPIS), answering poisons enquiries from vets, and in 2016 was promoted to her current role as head of service. In 2017, Nicola launched Animal PoisonLine, the 24-hour advice line for pet owners run by the VPIS.

References

- American Academy of Clinical Toxicology and European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists (1999). Position statement and practice guidelines on the use of multi-dose activated charcoal in the treatment of acute poisoning, Journal of Toxicology: Clinical Toxicology 37(6): 731-751.

- Bates N and Edwards N (2024). Saltwater emetic in pets: an inappropriate and potentially fatal treatment, Clinical Toxicology 62(Supp 1): 107.

- Beasley V (1999). Diagnosis and management of toxicoses. In Beasley V (ed), Veterinary Toxicology, International Veterinary Information Service, Ithaca.

- Jerzsele Á, Karancsi Z, Pászti-Gere E, Sterczer Á, Bersényi A, Fodor K, Szabó D and Vajdovich P (2018). Effects of po administered xylitol in cats, Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 41(3): 409-414.

- Chyka PA, Seger D, Krenzelok EP and Vale JA (2005). Position paper: Single-dose activated charcoal, Clinical Toxicology 43(2): 61-87.

- De Groot R, Veling WMT, Offereins N and Meulenbelt J (2008). When the remedy is worse than the poisoning: the use of table salt as a household emetic, Clinical Toxicology 46(5): 383-384.

- Dorman DC (1990). Toxicology of selected pesticides, drugs, and chemicals. Petroleum distillates and turpentine, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 20(2): 505-513.

- Handley HG and Hovda LR (2021). Risks of exposure to liquid laundry detergent pods compared to traditional laundry detergents in dogs, Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 31(3): 396-401.

- Ho B, Bates N, Edwards N, Robinson N and Ellison J (2020).Under-recognised effects on our canine and feline companions with 5-fluorouracil use, British Journal of Dermatology 182(3): 819.

- Humm K and Greensmith T (2019) Intoxication in dogs and cats: a basic approach to decontamination, In Practice 41(7): 301-308.

- Niedzwecki AH, Book BP, Lewis KM, Estep JS and Hagan J (2017). Effects of oral 3% hydrogen peroxide used as an emetic on the gastroduodenal mucosa of healthy dogs, Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 27(2): 178-184.

- Obr TD, Fry JK, Lee JA and Hottinger HA (2017). Necroulcerative hemorrhagic gastritis in a cat secondary to the administration of 3% hydrogen peroxide as an emetic agent, Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 27(5): 605-608.

- Pouzet-Nevoret C, Descone-Junot C, Loup J and Goy-Thollot I (2007). Successful treatment of severe salt intoxication in a dog, Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 17(3): 294-298.

- WHO (2020). Guidelines for establishing a poison centre, tinyurl.com/55cbrzax

- VPIS case data.

- Young B, Jansen R, Kirk J and Dellavalle R (2024). 5-Fluorouracil toxicosis in our pets: a review and recommendations, Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 90(5): 1,051-1,052.