11 Nov 2025

Kelly Druce PgDipVetEd, BSc(Hons), DTLLS, FHEA, RVN outlines her session, which will cover how student VNs integrate knowledge into clinical practice.

Figure 1. Practical elements of nursing are vital to student learning.

It will come as no surprise to those working in health care that nursing requires a diverse set of practical skills and underpinning knowledge to enable safe, effective and competent patient care (Nielsen et al, 2013).

Much human nursing literature promotes the importance of understanding the relationship between skill and knowledge, and despite a paucity of literature specific to the veterinary nursing (VN) profession, much is transferable as we recognise the similar challenges when combining classroom and clinical learning.

Many nursing students place great value on development of their clinical skills (Morrell-Scott, 2023) and deem these to be the most important aspect of their training, and immediately needed post-registration.

While some may argue this to be true and place disproportionate value on mastering these skills, this can inadvertently lead to areas of the taught curriculum being approached with a superficial learning style (Morrell-Scott, 2023), contributing to the theory-practice gap that has been considered a long-standing issue in nurse training and education, and describes the difference between what is learned in the classroom and what is encountered on clinical placement (Tambunan, 2024).

With high demands on VN students, it is natural for them to adopt different strategies for learning, with many focusing attention on areas they find personally stimulating (Richardson, 2007) and often involving practical elements of nursing (Figure 1).

Entwistle (1997) described three domains of learning: surface, strategic and deep, proposing these styles are less affected by individuals’ characteristics and more influenced by learning environments. These domains remain applicable today when considering the journey from student to qualified VN, whereby first-year students initially demonstrate surface-level approaches to learning, enabling them to cope within the clinical environment, explore new skills, and focus on memorising how to complete tasks.

As knowledge and confidence grows, many students naturally move to the next domain of learning, strategic learning, whereby their aim shifts towards achievement. This may be understandably linked to VN course structure, combining completion of the nursing progress log (NPL), with success in OSCE examinations. Students therefore learn to place greater value in knowledge relating directly to clinical nursing (Morrell-Scott, 2023) and needed for qualification, as opposed to building and developing knowledge in relation to the wider nursing curriculum and the nurse’s holistic role.

The final domain of learning described by Entwistle (1997) is deep learning, focusing on understanding wider concepts, building knowledge from experience and recognising value in knowledge. This is especially important when considering clinical decision-making pertinent to patient care and may be described as the ideal learning domain that we should encourage our students to strive for when in placement.

A VN needs to integrate knowledge into clinical practice, bringing together skills to make effective and appropriate decisions, while maintaining professional and ethical behaviours (Benner et al, 2010). Educational approaches to student training should promote knowledge application and decision-making so students are provided with opportunities to develop critical thinking skills, aiming to improve historic issues whereby nursing students feel under-prepared for life as qualified professionals (Morrell-Scott, 2023). For this to be achieved, educators in practice are instrumental in facilitating a shift from surface learning promoting task-focused patient care, towards deep learning and a patient-focused approach.

Task-focused nursing is common in human and veterinary fields, more so in student and novice nurses, and is largely accepted as part of the natural journey towards developing competence (Bourgault, 2023). This nursing style may be perceived as having many benefits, including improved control of busy wards and timely administration of medications.

Nursing students involved in repetitive tasks often become proficient quickly and those lacking experience take comfort from the instructive nature of the working environment (Bourgault, 2023).

Limitations to task-focused nursing should also be considered. Patient interaction is often reduced, leading to delayed recognition of clinical change, and reduced provision of holistic needs. Lack of autonomy, decision-making and professional development can negatively impact job satisfaction, and burnout is common due to constant time pressures relating to patient care (Kirkpatrick 2024).

Nurses are focused on task completion, directly hindering knowledge application, obstructing development of decision-making skills, while reducing clinical confidence and the ability to adapt to patients changing needs (Kirkpatrick, 2024).

Task-focused nursing may develop due to the segregation of theoretical and clinical knowledge within nurse education (Morrell-Scott, 2023), alongside a combination of time-sensitive goals set by the awarding body, and clinical practice placing disproportionate importance on SOPs, time management and completing required checklists (Kirkpatrick, 2024). This can lead to a de-appreciation of holistic nursing care and misalignment between what we teach our students in the classroom and what they are exposed to in clinical practice.

Moving towards patient-focused (or holistic) nursing offers many benefits and is associated with improved patient outcome and experience while hospitalised (Kwame and Petrucka, 2021). The term “patient focused” is becoming increasingly used in comparison to holistic nursing, which was originally introduced to recognise the unique individuality of care that humans require, but was often misinterpreted and linked solely to spiritual care and alternative therapies (Ballantyne, 2014).

Patient-focused care encourages the use of evidence-based nursing alongside care plans and care bundles (Ballantyne, 2014) to encourage individualised care that moves focus away from task completion and incorporates the patients emotional and social needs as well as their physical nursing needs.

Patient-focused nursing can bring many benefits, including enhanced job satisfaction for nurses (Abugre and Bhengu, 2023). This may be due to increasing opportunity for professional development, increased nurse autonomy and more “hands-on” nursing being undertaken (Figure 2).

Task-focused nursing can misalign with nurses’ core professional values leading to moral anguish and reduced job satisfaction (Sharp, Mcallister and Broadbent, 2018). Taking time to understand more about our patient’s condition, individual presentation and wider care needs is essential in acquiring the breadth of information needed for effective nursing decisions to be made (Levett-Jones et al, 2010) and can reduce unnecessary treatments and unexpected (costly) complications.

To optimise patient care, we must move away from completing isolated tasks and instead consider patients individuality, clinical condition, treatment plan and anticipated complications as one entity. It is the ability to apply knowledge and view patients holistically that enables rapid recognition of clinical change, allowing us to respond appropriately by making well-considered clinical decisions (Purling and King, 2012).

To encourage students to apply knowledge in clinical placement we must be mindful of their previous experience in clinical practice and the classroom. Task-focused nursing may be appropriate for those in early stages of learning or experiencing elements of practice for the first time, and timely administration of medications such as analgesia or insulin support a task-focused approach.

As students develop and progress through their training, we should encourage them to engage with, and assess, their patients fully, prior to undertaking procedures or administering treatment. Knowledge application describes the process by which our students translate and use what they have learned to improve their clinical practice (Ominyi and Alabi, 2025) and this can be encouraged alongside evidence-based veterinary medicine, another essential component of nurse education, which should be visibly used when working with students in the clinical environment so they can appreciate how research is implemented into practical aspects of nursing (Ominyi and Alabi, 2025).

Students experience many challenges and barriers when applying knowledge in the clinical setting and the reasons for this include poor communication between classroom and placement, lack of clinical staff to deliver training, inconsistencies within training and a disregard for problem-solving techniques in practice (Tambunan, 2024). It is essential for clinical learning that students are encouraged to verbalise their thoughts and openly discuss what they know and do not know, what they expect to happen and how they may need to respond.

When students do not actively participate in clinical teaching, an inability to build connection between clinical placement learning and what they have been taught in lectures is likely to occur (Tambunan, 2024). Often students are unaware of their knowledge gaps, which may result in a lack of further knowledge exploration. In human nursing it is reported that while student nurses place great focus on learning how to safely administer medications, they lacked knowledge of potential side effects or other information essential for administration (Morrell-Scott, 2023).

Clinical staff working alongside students are vital in encouraging them to apply and build knowledge in practice and are instrumental in providing context to real life nursing care. Using case studies for discussion, encouraging problem solving, enabling students to experience all aspects of the nurse’s role and encouraging reflection, all support the application and development of knowledge and can be easily facilitated in the clinical environment (Figure 3; Tambunan, 2024).

Students should be encouraged to ask questions to identify gaps in their knowledge and be provided with structured opportunities to reflect on nursing care, increasing opportunities for knowledge application and providing support for them to make sense of patient outcomes and the decisions that have led to these (Sherwood, 2024).

Clinical decision-making is an essential part of developing competence, enabling nurses to recognise at-risk patients and make timely decisions regarding their care (Levett-Jones et al, 2010). To do this effectively and advocate for patients, nurses must recognise signs of clinical deterioration and understand the patient’s individual situation and condition to enable effective change to be made to their nursing care (Johnsen et al, 2016). Following changes, it is important to evaluate and reflect on outcomes, so further knowledge development can take place (Johnsen et al, 2016).

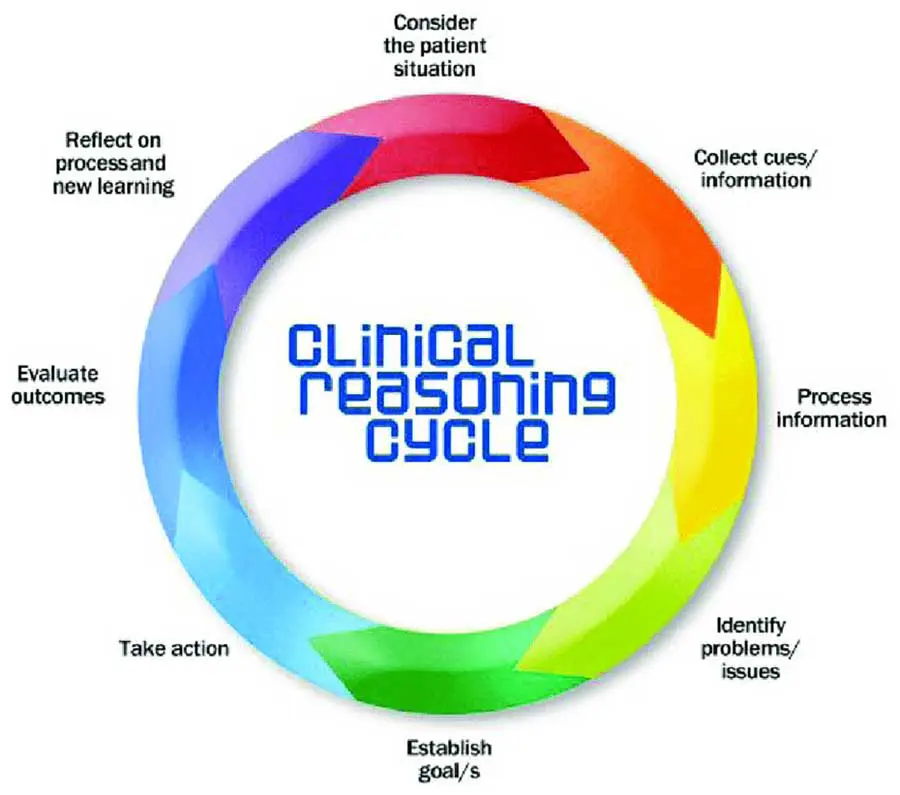

A task-focused learning approach may not enable this critical exploration of the patient, resulting in missed cues and subsequent patient deterioration. Students can develop critical reasoning and decision-making skills in a clinical environment that encourages questioning and discussion (Henderson, 2012) and the “five rights of clinical reasoning” and “clinical reasoning cycle” (Levett-Jones et al, 2010) are tools available to encourage patient-focused nursing through knowledge application and effective decision making.

Learning to integrate knowledge and make decisions does not just happen through observation alone (Levett-Jones et al, 2010), reiterating the need for student engagement, discussion and reflection to support the transition to patient focused nursing care.