23 Jun 2020

Kit Sturgess discusses the general factors to consider for these patients, engaging owners in their care and ensuring routine checks.

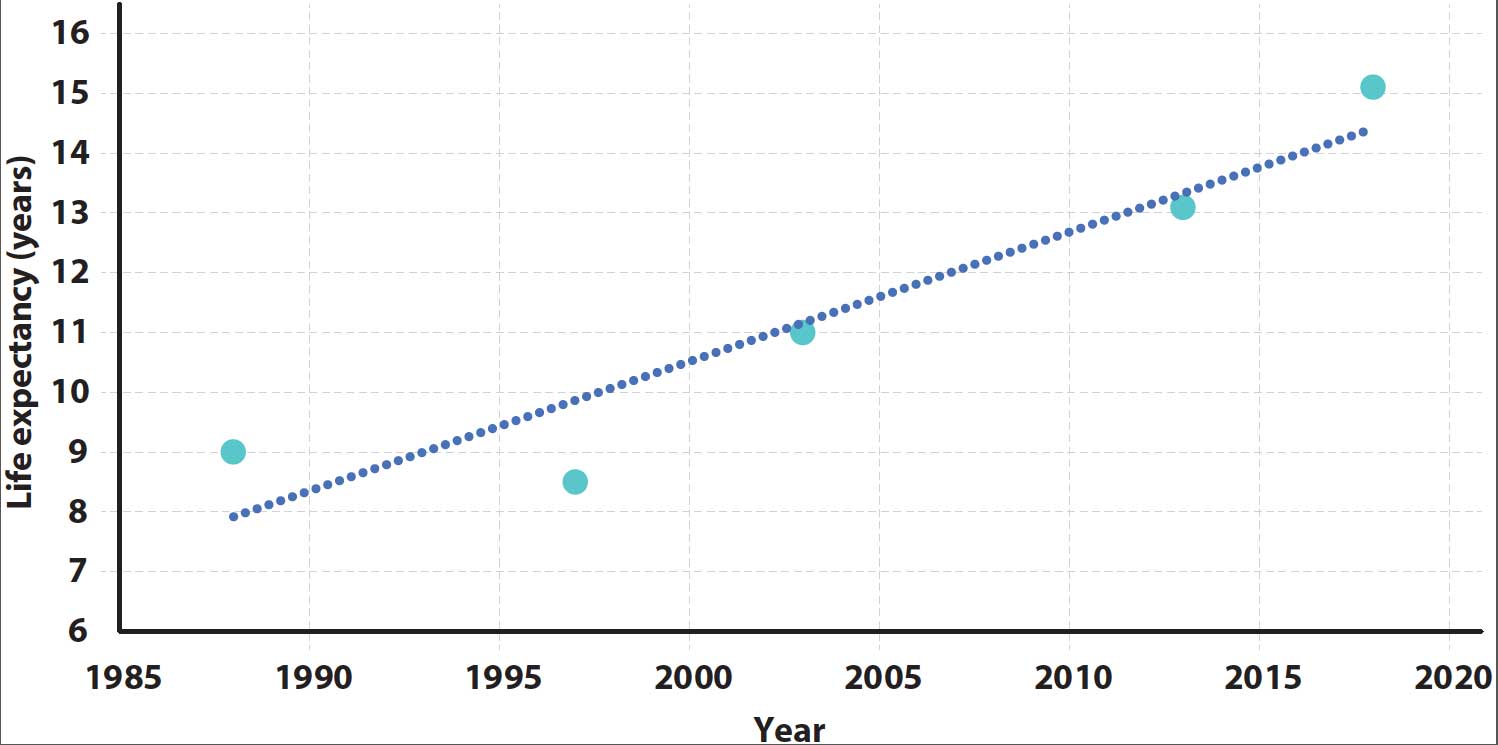

The life expectancy of our canine patients is increasing through better husbandry and veterinary care.

As a consequence, veterinary professionals are treating older dogs that have more than one progressive, non-curable condition often requiring relatively complex management plans, with considerations made regarding frequency of checks, interaction of medications, quality of life and recognising new problems as they arise.

This article will focus on the general factors to consider when managing our older canine patients to maximise life quality and longevity, engaging their owners in their care and ensuring appropriate checks are undertaken at suitable times – both in disease course and financially for the owner.

The average life expectancy of all dogs in the UK is 12 years (O’Neill et al, 2013), but this hides a wide variation – the longest‑lived breeds were the miniature poodle, bearded collie, border collie, West Highland white terrier and miniature dachshund, averaging 13.5 to 14.2 years; while the shortest-lived were the dogue de Bordeaux and great Dane, at 5.5 to 6 years.

Average life expectancy does seem to be increasing and would predict that average life expectancy of cross‑breed dogs would be about 14.8 years in 2020 (Figure 1).

This means what we consider “old” is changing and will vary with breed.

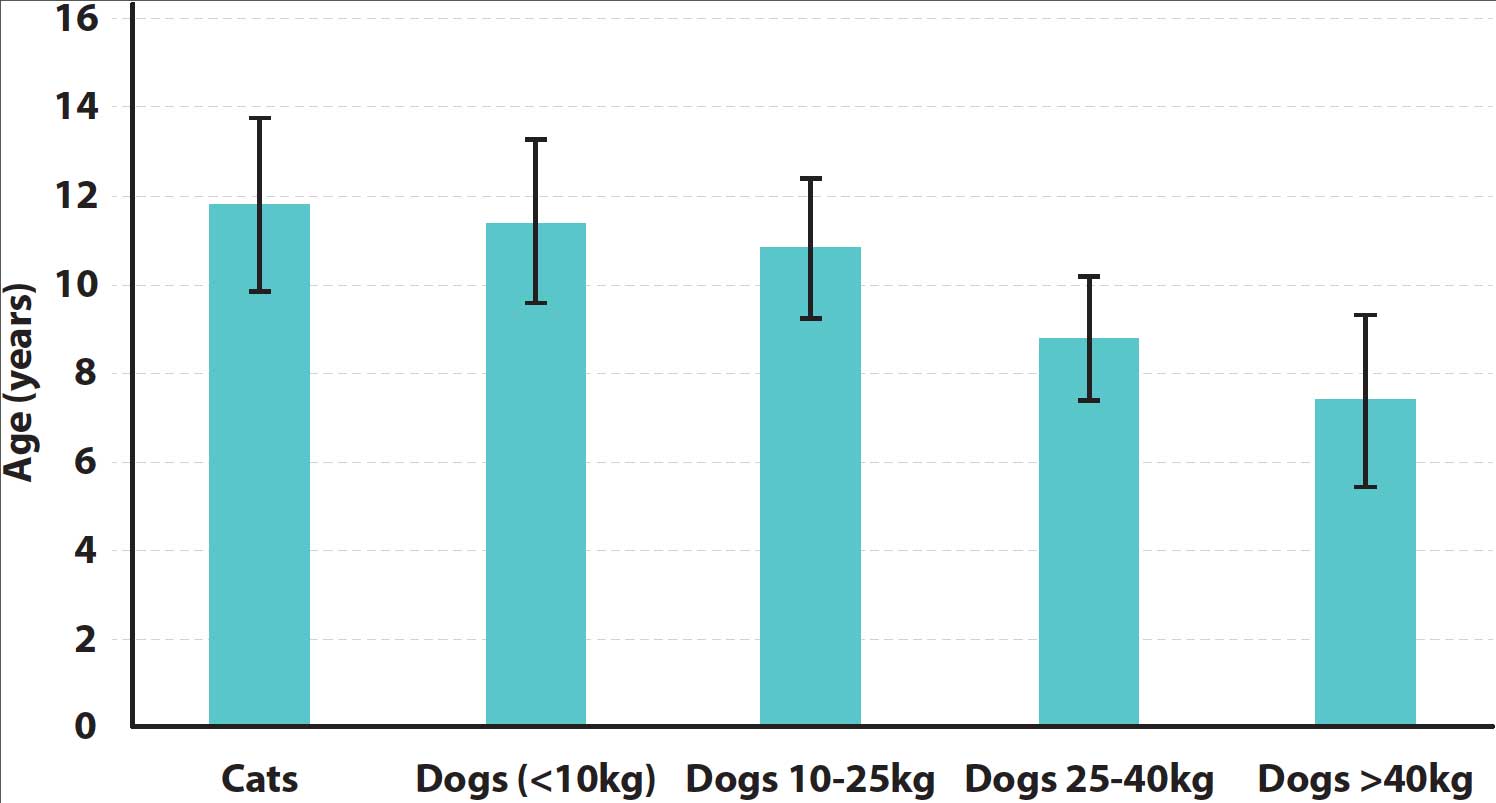

A general consensus exists that small and medium‑sized dog breeds are old (senior) between 11 and 12 years of age – and considered geriatric when older than 15 years of age – with age-related disease occurring sooner with increasing bodyweight (Figure 2).

Large and giant breeds are considered old by 7 to 10 years of age, and it is rare for giant breed dogs to reach 15 years of age (Table 1). Based on these data, a giant breed dog would be considered geriatric at 11 to 12 years of age.

| Table 1. Life expectancy of giant breeds compared to small breeds | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| P<0.0001 | % alive older than 10 years of age | % alive older than 15 years of age | |

| Small breeds | 38 | 7 | |

| Giant breeds | 13 | 0.1 | |

Using age alone as a definition of a patient being geriatric has potential dangers, as ageing is also influenced by genetics and lifestyle; therefore, it is necessary to include other subjective parameters into any assessment.

Inevitably, as dogs age they will become less active, sleep more and lose some sensory perception. Geriatric dogs also tend to interact less with their environment and eat less often, with gradual weight loss.

Rate of change does not necessarily follow a linear path, but rate of progression is slow and multiple parameters are affected. Significant changes over weeks to a few months should be viewed with suspicion, suggesting a disease is present beyond the normal ageing process – particularly if one area is affected significantly more than others. Specifically, sudden weight loss, marked behavioural changes, increased water intake or reduction in activity requires further investigation.

Chronic, slowly progressive diseases – such as OA or dental disease – are the most difficult to distinguish from normal ageing. Decisions to intervene are facilitated by regular check‑ups that should be every four to six months in geriatric patients, ideally associated with a standardised and repeated quality-of-life assessment at each visit and mandatory weight checks.

During routine check-ups, consideration should be given to nutrition, exercise, parasite control and vaccination.

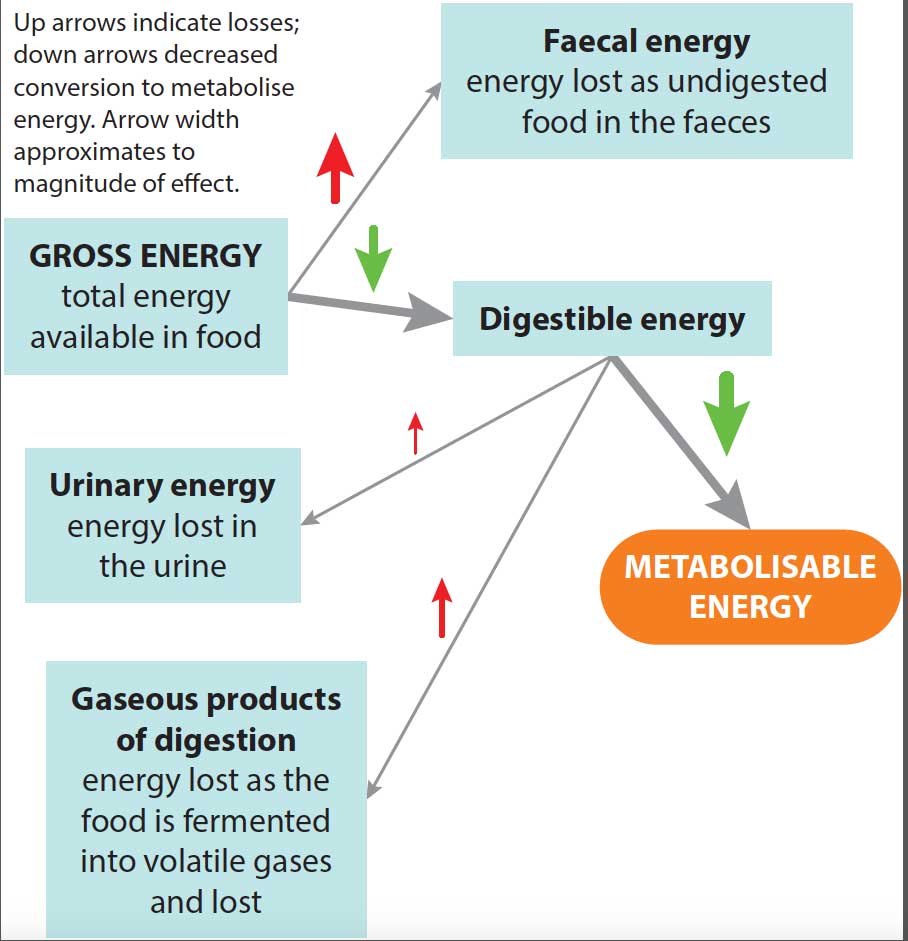

Optimal nutrition for maintaining health in elderly dogs is unknown. As dogs age, digestive function declines, starting as early as seven to eight years of age, resulting in effectively a lower digestible energy (Figure 3). Chronic disease may increase energy demands and inactivity lower them.

The gross energy requirement is, therefore, difficult to calculate, and best managed by ensuring bodyweight, muscle mass and condition is maintained. Appetite will often be reduced in geriatric patients.

Most “senior” diets are formulated with increased digestibility and palatability through protein and carbohydrate source, and a reduction in fat. Additionally, efforts have been made to manage some of the common ageing changes – such as reduced renal and cognitive function; ability to scavenge free radicals; and sarcopenia by altering levels of amino acids, essential fatty acids, vitamins and minerals.

Currently, impact on longevity is unknown; impact on quality of life needs to be assessed on an individual patient basis.

About 2.5% of dogs older than 10 years of age in one study (Batchelor et al, 2008) were found to have Toxocara eggs in their faeces, suggesting the risk:benefit ratio is still in favour of worming – particularly in older dogs that may be gradually losing weight and whose appetite is poor.

Risks of more serious parasitic disease – such as Angiostrongylus – remain and no evidence exists of a decline in prevalence of ectoparasites; indeed, reduced grooming may increase burdens.

Whether to continue vaccinations requires careful consideration in geriatric dogs, as some have little or no contact with other dogs. Local disease prevalence is also an important factor in decision‑making.

The consequences of low contact are:

This low risk needs to be balanced against:

On balance, for dogs with a stable household that receive routine health checks, the costs (in terms of other health care not provided) for particular clients outweigh benefits. However, such dogs are particularly vulnerable if a new dog – especially a puppy – is brought into the household.

For all other geriatric dogs, benefits of vaccination are likely to outweigh risks. The impact on terms and conditions of health insurance also need to be considered.

Beyond routine results from history and physical examination, data from routine blood, urine and faecal samples are often collected – and this may be augmented by data generated by wearable technology, such as activity monitors.

The problem with these additional data is centred around what to collect, and how they should be collated and fed into the individual’s care plan in a meaningful way to prompt changes in management that will alter quality of life or longevity.

At this time, we are far better at collecting data than at analysing and using the data gathered. It is, therefore, difficult to justify routine laboratory testing in an elderly dog whose clinical status has remained unchanged since the previous examination.

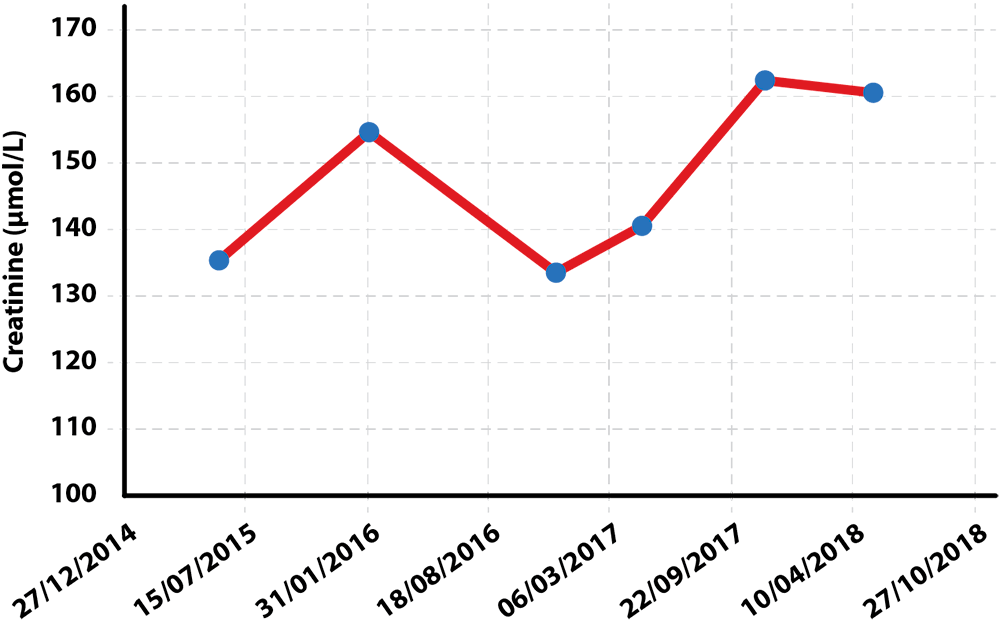

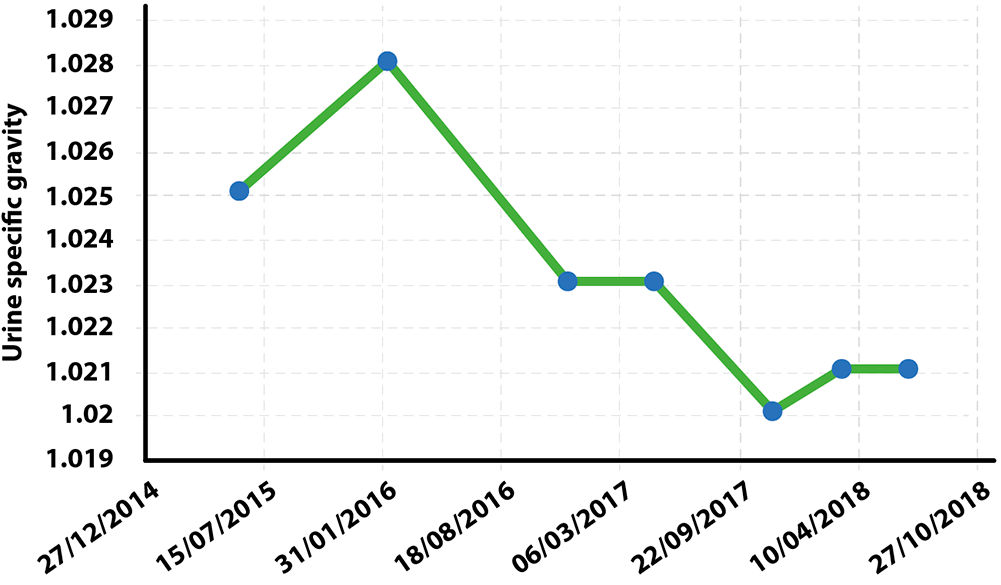

Individual care plans are a great concept and, as far as possible, should be centred around what is known about any chronic disease issues. For this to be useful, it needs to be easily accessible – such as a summary table in the patient notes that includes known/suspected diagnoses, results of serial diagnostics, current status and medication (Table 2; Figures 4 to 6).

| Table 2. Summary table for a 12-year-old, neutered female Labrador retriever | ||

|---|---|---|

| Condition | Status | Treatment |

| Elbow OA | Currently well controlled | Robenacoxib (40mg orally every 24 hours), glucosamine and chondroitin; occasional tramadol |

| Degenerative disc disease | Currently well controlled | |

| Hypothyroidism | Waiting follow-up thyroxine levels in four weeks to increase levothyroxine dose | 0.4mg levothyroxine orally every 12 hours |

| International Renal Interest Society stage-two chronic kidney disease | Slowly progressive | Diet discussions ongoing with owner; four-monthly urine specific gravity |

| Grade two mast cell tumour removed (right rib six) | Remission | No treatment |

| Chronic multidrug-resistant coliform urinary tract infection (UTI) | Currently culture negative | None |

| Right-sided grade two to grade three harsh localised murmur – point of maximal intensity mid apex-base | Observe | None |

| Mild, bilateral incipient cataracts | Observe | None |

| Weight loss and reduced appetite | Under investigation | Omeprazole |

| Treatment alerts | • Care with immunosuppressive drugs – risk of UTI. • Care with glucocorticoids – recurrence of UTI, cardiovascular disease, current NSAID use. • Adverse reaction to gabapentin – marked sedation. |

|

Collating and updating changes in medication – including supplements and nutraceuticals – is particularly important as new issues arise to minimise the risk of adverse drug interactions, such as administration of glucocorticoids for chronic bronchitis in a patient already on NSAIDs for chronic OA, for example.

Equally, if a new issue is identified, its impact on other known disease states can be assessed – for example, development of congestive heart failure in a patient with chronic renal disease requires careful consideration of the type and level of diuresis prescribed, and the effect vasodilation may have on glomerular blood flow.

For many older dogs, a need may also exist to map the presence and changes in cutaneous lumps and bumps, although, for some, this can be very time-consuming, so a decision on which types of lumps to record – for example, ignore nodular sebaceous hyperplasia – needs to be made.

When older patients require investigation or treatment, such as dental work, sedation or anaesthesia is often required.

This is often the most concerning part of the procedure for owners, and consideration needs to be given as to which drugs to use and at what dose.

In the author’s experience, it is the dose, rather than the drug, that is important. Older patients may be coping well with their chronic disease states and the system appears more robust than it actually is; higher dose rates can lead to much more profound effects than would be expected.

A general approach would be:

Increasing recognition exists of “senility” as a problem in older – particularly geriatric – dogs.

Clinical signs can often be subtle and involve a number of changes in behaviour. It can also be difficult to distinguish early signs of cognitive dysfunction from structural disease that is affecting brain function (Table 3).

| Table 3. Differential diagnosis of cognitive dysfunction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic illness | Structural brain disease | Reduced sensory acuity | Primary behavioural problem |

| • Thyroid disease • Pain • Chronic renal disease • Hepatic encephalopathy • Urinary/faecal incontinence |

• Granulomatous meningoencephalitis • Neoplasia |

• Loss of hearing or vision • Reduced sense of taste and smell |

• Aggression • Separation anxiety • House soiling • Compulsive disorder |

Signs of cognitive dysfunction have been recognised in 65% of dogs aged 15 to 16 years, and commonly include disorientation, changes in interaction with the owner and other pets, changes in sleep-wake cycle, house soiling and activity changes. Increasing agitation, altered response to stimulation, altered interest in food and decreased ability to perform learned tasks are also described.

These changes are associated with structural alteration in the brain at postmortem, including cortical atrophy, ventricular widening and plaque accumulation.

Management is based on dietary manipulation increasing antioxidants, mitochondrial cofactors and coenzyme Q, use of drugs such as selegiline or propentofylline, and vitamins/nutraceuticals (vitamin E, pyroxidine, phosphatidylserine, ginkgo biloba). Benefit has been shown in dogs using these regimes.

Increasing numbers of small animal patients fall into the elderly category where single, curable disease becomes a much less likely presentation.

Many of these patients have multiple chronic, age-related problems, so it is critical owners are aware that the focus is on management and support of the patient.

For this to be effective, data should be recorded, interpreted and stored in an easily accessible way, and an individualised care plan developed that highlights the data that are of value and guides the clinical response considered as those data change.