18 Jan 2016

Treating neck pain in dogs – neurological five-step approach

Johnny (Ioannis) Plessas looks at diagnosing some of the most common causes of pain in this part of the canine body and assessing the best form of treatment.

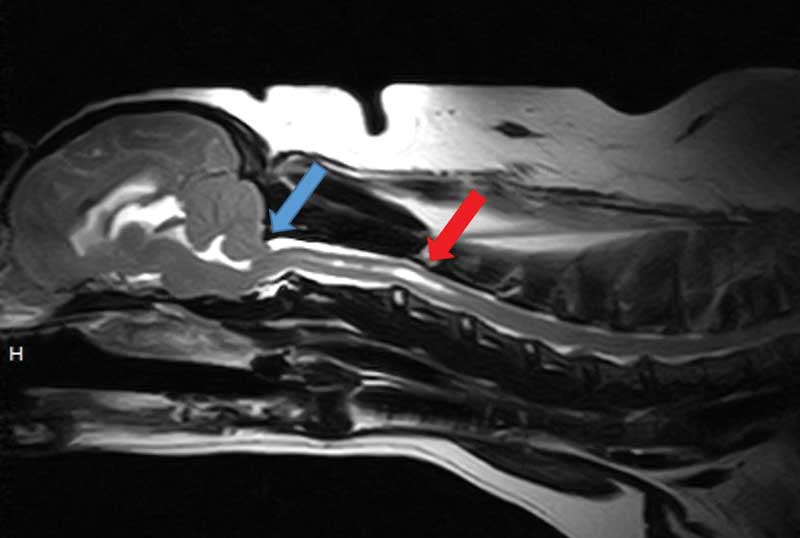

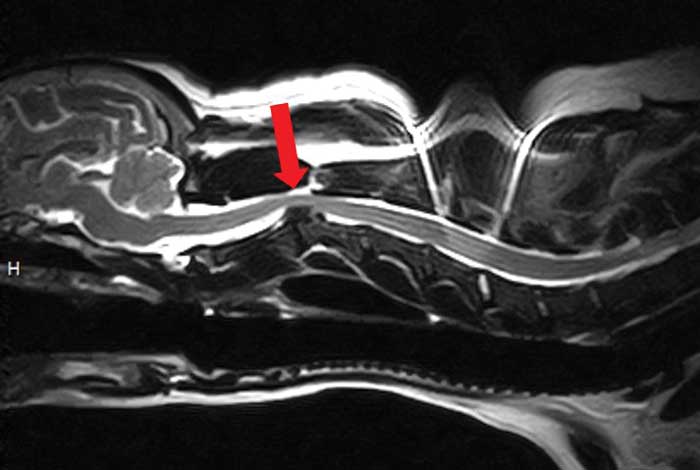

Figure 3. An MRI study of the head and neck of a three-year-old cavalier King Charles spaniel presented with intermittent episodes of neck pain. This sagittal T2-weighted image revealed mild Chiari-like malformation (blue arrow) and syringomyelia affecting the cranial cervical spinal cord (red arrow).

Neck pain is a common presenting complaint in small animal practice. In this article the author uses a practical, step-wise diagnostic approach and discusses management of common conditions. Signalment history, physical and neurological examination, creating a list of differentials, reaching the diagnosis and selecting the most suitable treatment are five easy steps to implement on any case with history of neck pain. The age group and presence of neurological deficits or not is also very useful information to shorten the list of differentials. When present, neurological deficits associated with neck pain are often referable to C1 to C5 or C6 to T2 spinal cord segments (tetraparesis/hemiparesis, ataxia, reduced postural reactions on all four limbs in the absence of cranial nerve deficits and normal mentation). However, sometimes neck pain can be the main manifestation of an intracranial disease or a multifocal problem. Deficits from other parts of the nervous system may also be present.

Using the mnemonic VITAMIN D, the most common causes are discussed, as well as how to create a relevant list of differentials based on history and examination findings. Having the most likely differentials in mind, clinicians can select the most appropriate tests to reach a diagnosis.

Neck pain is a common presenting complaint in dogs and can arise due to many different causes.

Analgesia can alleviate the pain temporarily, but, unless the underlying cause is addressed, the pain can quickly relapse or become difficult to control.

A systematic approach to cases presenting with neck pain can help clinicians create a list of differentials and plan a diagnostic investigation wisely.

Although examining the neck may seem an obvious place to start, clinicians should always begin with a detailed history and thorough physical examination. A neurological examination should then be performed to distinguish whether the neck pain is associated with neurological deficits or not. If deficits are present, they can help localise the part of the nervous system affected.

The anatomical basis of neck pain reflects involvement of at least one of the following structures: muscles, meninges, nerve roots, intervertebral disc (annulus fibrosus) or vertebrae (including articular facets)1. Various mechanisms can affect these to cause neck pain, but usually it is the result of inflammation, compression or destruction2.

Sometimes, the main cause of neck pain is not localised in the neck. For example, brain space-occupying lesions can increase the intracranial pressure and affect the normal CSF flow, resulting in neck pain. Likewise, neck pain may be part of a multifocal problem.

Signalment and client history

Knowing the breed and age of the dog is an important first step in your investigation.

Chondrodystrophic breeds may be prone to intervertebral disc extrusions, whereas young dogs may be susceptible to inflammatory diseases – for example, meningitis – or malformations of the vertebral column, such as atlantoaxial subluxation.

A detailed history should be obtained from every case presenting with signs of neck pain. Information about the onset (acute versus chronic), progression and history of trauma can help to rule in or out diseases.

Ruling out non-neurological causes

A thorough general physical examination should be performed in every case. Findings from the physical examination may give you clues about the underlying cause of pain.

Not all causes of neck pain are due to a neurological disease. For example, stick injuries in the oropharyngeal area, severe otitis associated with para-aural abscessation or salivary gland diseases, such as carcinoma, can present with neck pain.

Even when the general clinical examination does not give you a conclusive answer, it may give you clues about the underlying cause.

For instance, fever can be more associated with inflammatory or infectious diseases, multiple joint pain and effusion can be suggestive of polyarthritis and masses in other areas in the body can be connected to neoplastic lesions with possible spinal involvement.

Neurological examination

Neurological examination is essential for two main reasons: some causes of neck pain are associated with neurological deficits while others are not and the presence of neurological signs will help you localise the lesion to a portion of the CNS.

In most cases, the latter refers to a C1 to C5 or C6 to T2 cervical myelopathy or it may be suggestive of a lesion other than the cervical spinal cord, such as intracranial.

A complete neurological examination should include assessment of mentation, posture, gait, postural reactions, cranial nerves, spinal reflexes and spinal palpation.

Palpation of the neck should be the final part of the examination to avoid stressing the patient. Observation of the dog’s posture is very important, especially in stoic dogs or where examination is difficult. Most dogs will have a low head carriage and the neck is held in an extended position, avoiding flexion.

Ataxia in all four limbs, tetraparesis, delayed postural reactions with normal segmental spinal reflexes (C1 to C5 myelopathy) or reduced in thoracic limbs (C6 to T2 myelopathy) can be found.

Differential diagnosis

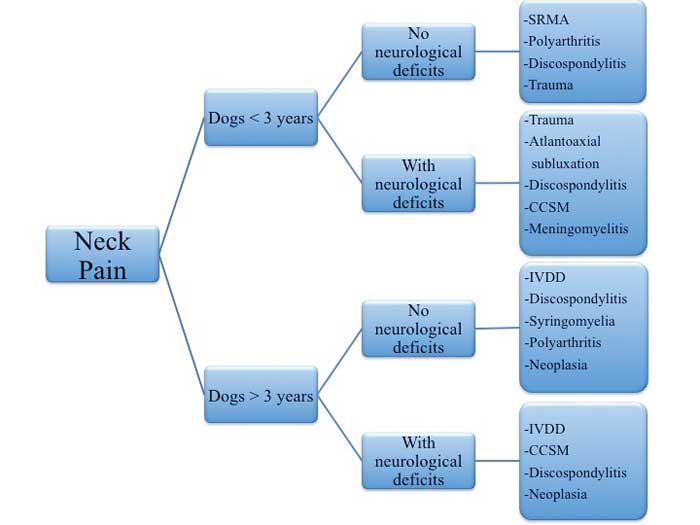

Cases with neck pain can be placed into two main groups based on their age: young dogs less than three-years-old and dogs more than three years old.

The age group and the presence or absence of neurological deficits (Figure 1), as well as whether the onset was acute or chronic, can be helpful when creating a list of differentials.

The mnemonic VITAMIN D can be useful in making sure important differentials are not missed.

Diagnosis and treatment

After creating a list of differentials, the appropriate diagnostic tests should be performed to achieve a diagnosis and treat the patients accordingly.

To conclude, a systematic approach to cases with neck pain is the key to correct diagnosis and treatment. Clinicians should always take a detailed history, perform a thorough physical examination and, most importantly, think outside the box in challenging cases.

- Some drugs mentioned in this article are used under the cascade.