26 Nov 2020

Treatment and management of otitis in dogs and cats

Filippo De Bellis and Hannah Lipscomb describe the clinical approach to this common presentation, as well as medical and surgical therapy options.

Figure 1. Erythema, excoriations and stenosis of the concave pinna of a Staffordshire bull terrier with atopic dermatitis.

Otitis is a common condition seen in veterinary practice and can prove challenging to treat.

To achieve successful treatment, it is important to address primary and secondary causes, and predisposing and perpetuating factors. Whenever possible, treatment should consist of a topical antibiotic and/or antifungal, ear cleaner and oral glucocorticoid; systemic antibiotics/antifungals are only required for selected cases.

Treatment is based on cytology and/or culture and sensitivity results, and the patency of the tympanic membrane; rupture of the tympanic membrane limits treatment and increases the risk of ototoxicity.

Imaging is helpful to further evaluate the ear, especially the middle ear, and establish treatment: medical versus surgical. Ear flushing should be considered in cases of chronic otitis externa and/or media to physically remove pathogens, biofilm and cerumen. When otitis media is diagnosed and the tympanic membrane is intact, myringotomy needs to be performed prior to flushing.

Once affected ears are in remission, proactive therapy can ensue – and typically consists of an ear cleaner and topical glucocorticoid.

The key to good long-term management is effective communication.

Otitis externa (OE) is one of the most common conditions seen in veterinary practice, especially in dogs1.

Very simply, OE is inflammation of the external ear canal (EEC), and the clinical signs observed are typically a combined result of an underlying primary problem, secondary infection and various factors2:

- Causes:

- Primary: foreign bodies, ectoparasites, allergies (Figure 1), endocrinopathies (Figure 2), autoimmune/immune-mediated diseases.

- Secondary: infection (Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and fungi).

- Factors

- Predisposing: obstruction, confirmation, aural environment, topical treatment effects (Figure 3).

- Perpetuating: pathological changes resulting from chronic OE, otitis media.

When pathology changes, a multidrug‑resistant mixed infection and otitis media (OM) develop, otitis can be a challenging condition to treat; recognition and correction of both causes and factors is key to successful treatment and management.

Clinical approach

To successfully treat otitis, veterinary practitioners should understand as much as possible about the patient and its ear disease.

A thorough history should be taken that covers lifestyle, disease onset and seasonality, skin lesions elsewhere and previous treatment. A full physical examination should be completed, followed by dermatological and otoscopic examination.

Otoscopy, if tolerated, should be performed in every patient with otitis as it is the only way to assess the ear canal and tympanic membrane (TM) in a conscious patient3. Along with otoscopy, ear swabs should be taken for in-house cytology as it helps determine treatment and the corresponding response.

Furthermore – in cases of chronic or unresponsive OE, concurrent OM and/or when rod-shaped bacteria are identified on cytology – ear swabs should be submitted for culture and sensitivity (C&S) testing4.

Treatment of OE and OM: medical

Once OE has been diagnosed, medical treatment can commence with topical and/or systemic therapy.

Topical therapy

Antibiotics

For cases of bacterial OE, whenever possible, antibiotics should be administered topically and based on cytology. Antibiotics available for topical use include fusidic acid, framycetin, gentamicin, neomycin, florfenicol, marbofloxacin, orbifloxacin and polymyxin B (Table 1).

| Table 1. Topical preparations (modified from Veterinary Prescriber) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Delivery | Licensing | Antibiotic | Antifungal | Glucocorticoid | Dosage |

| Aurimic | Drops | Dogs, cats | Polymyxin B | Miconazole | Prednisolone | Twice daily for at least 7 to 10 days, up to 14 days |

| Aurizon | Drops | Dogs | Marbofloxacin | Clotrimazole | Dexamethasone | Once daily for 7 to 14 days |

| Canaural | Drops | Dogs, cats | Fusidic acid Farmycetin |

Nystatin | Prednisolone | Twice daily for seven-plus days |

| Easotic | Pump dispenser | Dogs | Gentamicin | Miconazole | Hydrocortisone aceponate | Once daily for five days |

| Marbodex | Drops | Dogs | Marbofloxacin | Clotrimazole | Mometasone | Once daily for 7 to 14 days |

| Neptra | Drops | Dogs | Florfenicol | Terbinafine | Mometasone | Single treatment: 1ml per infected ear |

| Osurnia | Gel | Dogs | Florfenicol | Terbinafine | Betamethasone | Two applications, one week apart |

| Otomax | Drops | Dogs | Gentamicin | Clotrimazole | Betamethasone | Twice daily for seven days |

| Otoxolan | Drops | Dogs | Marbofloxacin | Clotrimazole | Dexamethasone | Once daily for 7 to 14 days |

| Posatex | Drops | Dogs | Orbifloxacin | Posaconazole | Mometasone | Once daily for seven days |

| Surolan | Drops | Dogs, cats | Polymyxin B | Miconazole | Prednisolone | Twice daily for as long as required |

In 2018, the BSAVA published the following recommendations for topical antibiotic selection and critically important antibacterials (bit.ly/3jQ0XLj):

- When cocci are seen on cytology, first‑line antibiotics include florfenicol, fusidic acid/framycetin or polymyxin B/miconazole.

- When rods are seen on cytology, first-line antibiotics include framycetin, gentamicin or polymyxin B.

- Fluoroquinolones should only be used when other antibiotics are contraindicated or ineffective and C&S testing indicates they will be effective.

Antibiotic sensitivity data aids antibiotic selection; nonetheless, it is important to recall that such data sets represent serum minimum inhibitory concentrations. Therefore, this data is less useful when considering topical antibiotics as they are between 100 times and 1,000 times more concentrated than systemic equivalents, potentially contradicting sensitivity data5,6.

When the TM is ruptured, the middle and inner ear are susceptible to receiving topical therapy intended for the EEC only, leading to ototoxicity of the inner ear: cochlear (deafness) or vestibular damage (vestibulopathy; Figure 4)7,8. As a precaution, otoscopy should always be performed prior to the initiation of topical therapy, but ototoxic agents can alternatively reach the inner ear via haematogenous distribution (for example, furosemide and several chemotherapy drugs).

Antibiotics that appear to be safe in both the middle and inner ear include gentamicin (aminoglycoside exception), fluoroquinolones and a few cephalosporins (for example, ceftazidime)7-9. However, despite studies and extrapolated data from human medicine, clients should always be informed about the risk of ototoxicity as topical medication may have unpredictable effects in pathological ears.

Alternative topical antimicrobials

Silver sulfadiazine has a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity and, although unlicensed, is highly efficacious against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. When used to treat OE, the cream should be dispensed into small syringes and mixed with sterile saline to create a homogenous emulsion5.

In conjunction with an antimicrobial, as a pre-soak or carrier vehicle, tromethamine‑ethylenediaminetetraacetate (TrisEDTA) should be considered; Tris acts as a buffer and EDTA increases the susceptibility of bacteria to antibiotics5. In vitro studies have revealed the antimicrobial effect of TrisEDTA to all the common microorganisms (for example, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, β-haemolytic Streptococcus species, P aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis and Malassezia pachydermatis) involved in the pathogenesis of OE10,11.

However, this wide spectrum of antimicrobial activity has been challenged; the in vitro study by Boyd et al (2019) demonstrated TrisEDTA to be potentially advantageous against P aeruginosa, but have no additional benefit for S pseudintermedius6.

Antifungals

Polyvalent ear medications contain an antifungal (Table 1): an azole or polyene.

Imidazoles (azole class) inhibit fungal growth by preventing ergosterol synthesis. Examples include clotrimazole, miconazole and posaconazole.

Nystatin is a polyene antifungal – technically it is a polyene antibiotic within a subgroup of macrolides – and has antifungal action by binding to ergosterol, affecting cell membrane permeability12.

When the TM is ruptured, experimental research has confirmed clotrimazole, miconazole and tolnaftate are all non-toxic to the middle and inner ear13.

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are incorporated into topical ear medications as they are anti‑inflammatory, antipruritic and antiproliferative, and reduce sebaceous and ceruminous gland secretions.

Glucocorticoid potency depends on intrinsic potency (Table 2), concentration and vehicle, and should be reviewed when selecting ear medication (Table 1)5,14.

| Table 2. Relative potencies of topical glucocorticoids (guide only) | |

|---|---|

| Potency | Glucocorticoid |

| Very potent (100 × hydrocortisone) |

Fluocinolone |

| Potent (25 to100 × hydrocortisone) |

Betamethasone Dexamethasone Hydrocortisone aceponate Mometasone furoate |

| Moderate (2 to 25 × hydrocortisone) |

Prednisolone Triamcinolone |

| Mild | Hydrocortisone |

Ear cleaners

Alongside medicated topical therapy, it is also important to include ear cleaning in the treatment protocol; cleaning aids the removal of debris, cerumen and discharge from the EEC, consequently enabling more accurate and deeper penetration of topical therapy.

Furthermore, cleaning can be particularly useful in cases of seborrhoeic, hairy, stenotic and pendulous ears.

Ear cleaners usually contain cerumenolytic, astringent and antimicrobial agents. An in vitro study by Swinney et al (2008) assessed the efficacy of various ear cleaners against the microorganisms Staphylococcus intermedius, P aeruginosa and M pachydermatis. The ingredients identified as having the greatest antimicrobial effect were isopropyl alcohol (astringent) and parachlorometaxylenol (antimicrobial agent), although the study conclusions may not be directly applicable to an in vivo scenario15.

After dispensing an ear cleaner, it is important to instruct clients how and when it should be applied; clients should apply ear cleaners directly into the EEC then simply allow head shaking to take place.

Generally, ear cleaners should not be applied more than every 48 hours, but in one study an ear cleanser was used twice daily for two weeks and caused no adverse reactions16.

Ear cleaning is most effective following an ear flush – and at this stage, the pH of the ear cleaner should be considered; EECs healing from severe pathology should receive something neutral.

Moreover, when selecting an ear cleaner, the patency of the TM should be known; one study reported squalene to be the only non‑ototoxic agent in ear cleaners, but other work has revealed chlorhexidine – at a concentration of 0.2% or less – and TrisEDTA to also be non-ototoxic17,18.

Systemic therapy

Antibiotics

Systemic antibiotics are rarely used to treat OE for the aforementioned reasons and to comply with antibiotic stewardship guidelines. However, they are indicated in cases of severe stenosis and ulceration of the EEC, and OM.

For OM, systemic antibiotics may be more efficacious than topical equivalents as the tympanic bulla is lined by a highly vascular mucous membrane; this vasculature allows antibiotic diffusion into the middle ear5.

Furthermore, systemic antibiotics should be selected based on C&S results from samples of the bulla content – and while results are pending, empirical treatment should commence.

Antibiotics identified as efficacious for OM include fluoroquinolones and cephalexin5,8.

Antifungals

In dogs, systemic antifungals are used off licence, and in dogs and cats they are reserved for severe cases unresponsive to a trial of topical antifungal19. The authors’ systemic antifungal of choice is itraconazole.

Glucocorticoids

Oral glucocorticoids have an important role in the medical treatment of OE: they reduce stenosis, oedema and hyperplasia of the EEC, and therefore improve otoscopy and cleaning14.

Moreover, patients awaiting an ear flush should receive a pre-emptive course of tapering, oral glucocorticoid.

Imaging, ear flushing and myringotomy

In cases of severe OE with or without clinical signs of OM, imaging is a helpful diagnostic to further evaluate the ear – especially the middle ear – and establish treatment: medical versus surgical.

Additionally, imaging of the ear is indicated in cases of para-aural swelling, fistulous tracts, trauma, inability to open the mouth, neurological dysfunction and nasopharyngeal polyps.

The most appropriate imaging modality to use in general practice, despite its limitations, is radiography; limitations include lack of sensitivity and difficulty interpreting radiographs due to subtle pathology. Radiography should be performed under general anaesthesia, and consist of left and right lateral oblique, dorsoventral skull and rostrocaudal (tympanic bulla) views.

In theory, radiography can expose occlusion and changes of the EEC, soft tissue opacity in the middle ear and lysis or proliferation of the bulla wall8,20. Furthermore, positive contrast canalography can be used to assess the integrity of the TM and involves introducing a soluble contrast medium into the EEC.

The diagnosis of TM rupture is relatively straightforward as contrast material is identified in the middle ear; however, if the canal is stenotic, extra scrutiny is required as stenosis can cause obstruction8,21.

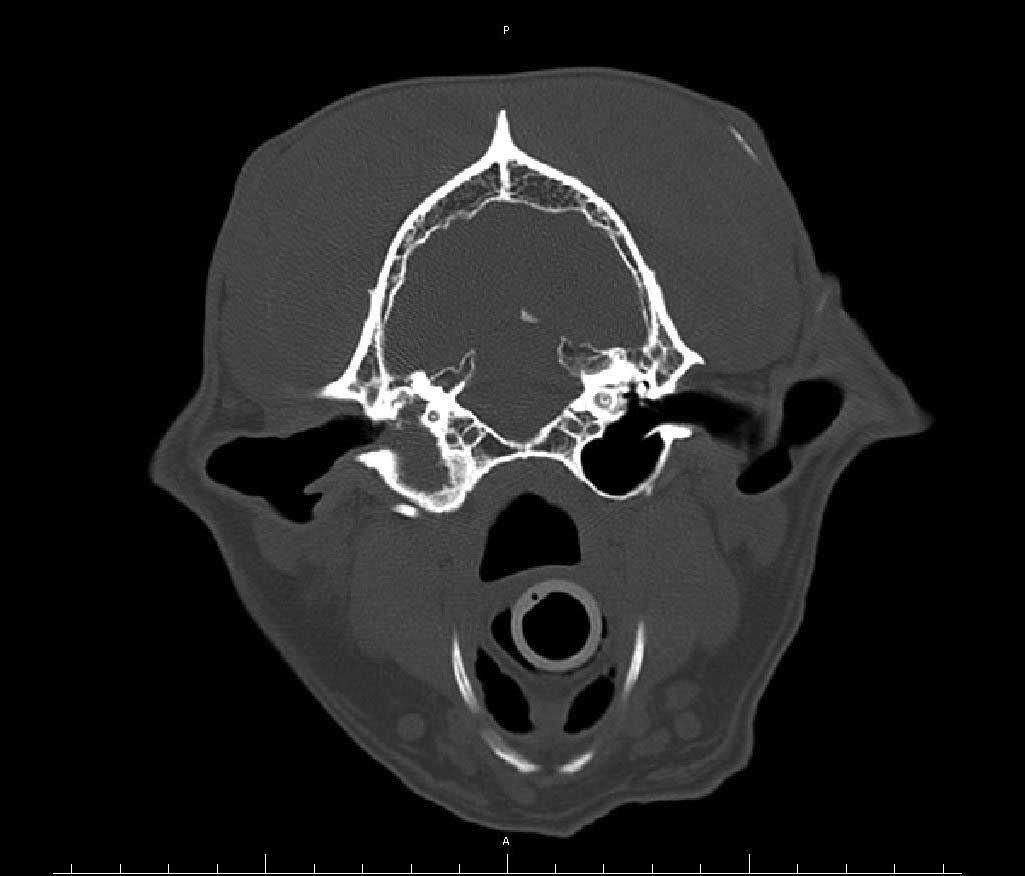

At a referral level, advanced imaging is performed: CT or MRI. CT studies are quick and easy to perform, and provide excellent images of the ear canal (stenosis), middle ear (soft tissue filling) and particularly bony structures (lysis; Figure 5).

MRI is more sensitive at detecting soft tissue lesions and is the modality of choice for neoplastic masses8,20. Disadvantages of MRI are the studies take time to perform and cost.

Ear flushing should always be considered for chronic cases of OE and/or OM to physically remove pathogens, biofilm and adherent cerumen. Although a low-risk procedure, prior to an ear flush clients should be informed about the potential complications of facial nerve paralysis, Horner’s syndrome, deafness and vestibulopathy22.

Patients undergoing an ear flush should be anaesthetised and intubated; the endotracheal tube should be cuffed to prevent fluid running from the middle ear to the nasopharynx via the Eustachian tube8.

Ear flushing can be performed using an otoscope, urinary catheter (6F) attached to a syringe (10ml), and sterile saline; and for referred patients, a video-otoscope. Additionally, before ear flushing and if the TM is intact, an ear cleansing solution should be applied to aid the breakdown and removal of cerumen.

Myringotomy is the iatrogenic rupture of the TM, and indicated in cases of OM to access the middle ear for sampling (cytology and C&S testing) and flushing. Before myringotomy is performed, the EEC should be thoroughly lavaged and allowed to dry. The technique involves advancing a urinary catheter (6F, cut obliquely at 60°; with a 2ml syringe attached) through the ventral and posterior quadrant of the TM, followed by flushing with sterile saline3,8.

Treatment of OE and OM: surgical

For some cases, despite great medical effort, surgery is considered the treatment of choice.

Examples of when surgery is required include severe stenosis and fibrosis or mineralisation of the EEC, osteomyelitis of the middle ear structures, masses in the EEC or middle ear, and para‑aural abscessation.

Long-term management of otitis

When cases of otitis have resolved, proactive therapy should ensue – this typically consists of an ear cleaner and topical glucocorticoid. Ear cleaners should be selected carefully – as aforementioned – and used as infrequently as possible.

Topical glucocorticoids are used to prevent the cycle of inflammation and infection, and the authors have successful experience using a hydrocortisone aceponate product – a measured volume is applied into the EEC on two consecutive days per week and with time is tapered and stopped23. This protocol is used off‑label, so informed consent is required.

An alternative proactive anti-inflammatory is triamcinolone acetonide used once or twice daily for a maximum of 14 days. Triamcinolone acetonide should only be used short‑term as it is a moderately potent steroid; therefore, prolonged use is associated with more dermatological and potentially systemic side effects24.

Ears in remission with proactive therapy should be monitored by having occasional recheck appointments. Once in remission, diagnostics can be performed to investigate the primary cause – for example, cases of suspected subclinical allergy can proceed with an elimination‑provocation dietary trial.

Finally, for allergic cases, clients should be informed otitis can occur at any point and topical therapy may be required for life; it is the veterinary practitioner’s responsibility to help clients understand the pathogenesis and treatment of otitis, and effective communication is fundamental for long‑term management.

Conclusion

Otitis can be a challenging condition to treat in veterinary practice; treatment and management are enhanced by thorough understanding of pathogenesis and correction of causes and factors.

Treatment should be based on cytology, and knowledge of the polyvalent ear medications available will ease treatment selection.

TM rupture with or without OM requires treatment that is safe for both the middle and inner ear; systemic treatment and surgery are only recommended for selected cases.

Chronic otitis should initially be investigated with imaging, proceeded by ear flushing under general anaesthesia.

Long-term management becomes important post‑infection resolution, and effective communication is fundamental for success.

- Some drugs mentioned in this article are used under the cascade.