14 Oct 2025

Sam Taylor BVetMed(Hons), CertSAM, DipECVIM-CA, PGCert(TLHE), FHEA, MANZCVS, FRCVS, explains how a combination of medication and cat-friendly handling can benefit patients, professionals and caregivers

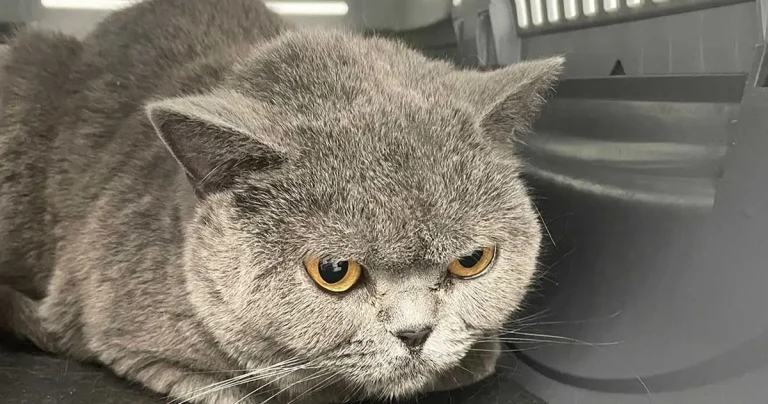

Figure 1. A cat showing signs of anxiety, such as flattened ears rotated backwards, narrowed eyes and whiskers splayed.

The Cat Friendly Clinic scheme from International Cat Care (www.icatcare.org) has done much over the past 12 years or so to improve a cat’s experience in the veterinary clinic, but many cats still seldom have health checks and are presented only if unwell and often late in the course of an illness.

A barrier to clinic attendance can be caregiver reluctance to present their cat if they are aware these visits cause the cat stress1. Additionally, anxious cats can be challenging to examine and treat, and potentially miss out on veterinary care.

This article focuses on such cats and how we can help mitigate stress when visiting the clinic with both pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical cat-friendly techniques.

Anxiety and fear are common emotions experienced by cats at the clinic, and involve the same emotional system. Pain can also be part of this system, and it is important to understand that unmanaged pain will worsen fear-anxiety2. Fear-anxiety and pain are “protective” or negative emotions (along with frustration), and can result in behaviours such as aggression (better described as “repelling” behaviour). Therefore, fear-anxiety and pain can reduce our ability to complete examinations and procedures, risk staff injury and reduce the cat’s mental well-being, affecting its welfare.

Various factors will influence the cat’s emotions during a clinic visit, including genetics, previous experiences, travel to the clinic, pain and illness, the clinic environment (sounds, sights, smells), interactions with people and even the caregiver’s emotions and behaviour3.

Fear-anxiety will also affect various clinical parameters (such as blood pressure, blood glucose or heart rate), rendering results unreliable. Anxious and fearful cats will show body language such as rotating ears to the side or back, whiskers splayed, eyes partially closed and a tense posture (Figure 1).

To read more about emotions and behaviours in the clinic, please read the 2022 American Association of Feline Practitioners/International Society of Feline Medicine (AAFP/ISFM) Cat Friendly Veterinary Interaction Guidelines via tinyurl.com/yydsvpf2

Stress (for both caregiver and cat) often begins on the day of the appointment when the cat carrier is brought out of the garage and dusted off.

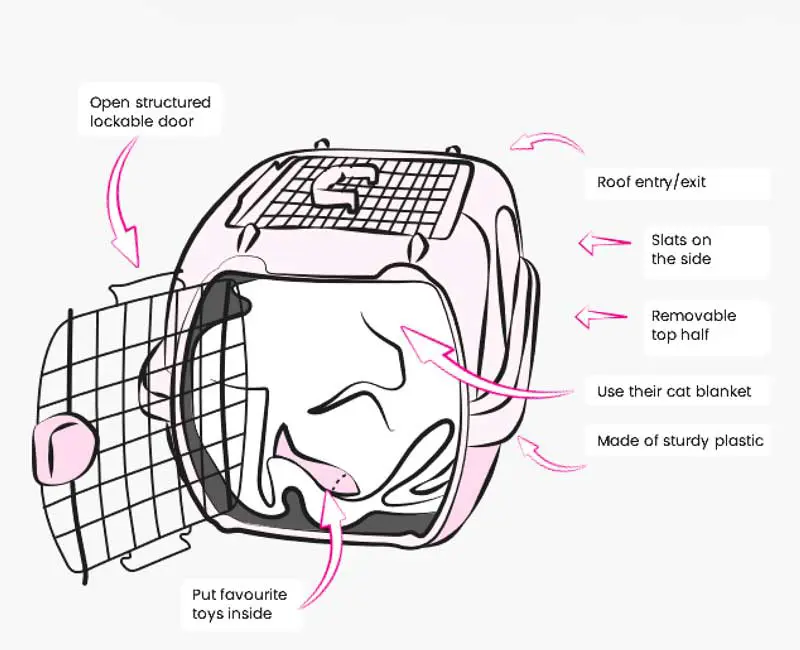

Unfamiliar carriers, confinement and lack of control can cause anxiety, and this can be mitigated by providing caregivers advice on the process of getting to the clinic.

Key points include:

Further information for clients can be found via the International Cat Care website (tinyurl.com/y9pda2m9) and emailed to new and existing clients.

Pain will exacerbate fear-anxiety in the veterinary clinic, and chronic pain in particular is likely underdiagnosed in this species; for example, osteoarthritis and dental disease are prevalent conditions. Restraint likely increases discomfort, and the negative experience will reinforce protective (negative) emotions associated with the clinic.

Additional analgesia prior to travel can generally be administered safely alongside anxiolytics and greatly improve a cat’s tolerance of examination, and reassure caregivers of their cat’s comfort in your care.

The use of pharmacotherapy to reduce protective emotions in the clinic has grown.

Medications such as gabapentin4, pregabalin5 and, less often, trazodone6 have been studied and used to reduce the stress of travel to, and examination in, veterinary clinics.

Pharmaceutical interventions can be very effective in reducing fear-anxiety and, therefore, mitigating negative experiences (and resultant conditioning) during transport and at the clinic.

Such treatment can facilitate examination, blood sampling, imaging and other minor procedures.

However, use of anxiolytics is not a substitute for a cat-friendly environment and gentle handling, and will not be effective in highly stressful situations and in cats with extreme fear-anxiety3. These medications should be used in combination with methods to reduce stress during examinations and procedures to achieve the optimal effects.

Anxiolytics may not be effective if the cat’s underlying emotion is frustration, rather than fear-anxiety; for example, a young bold cat resenting restraint for blood sampling.

In this latter situation, distraction (such as with treats or sedation) may be preferable. Each cat is an individual and may respond differently to anxiolytic medication, and trials can help identify the optimal protocol for each cat.

A cat-friendly environment separates species (sight, sound and smells) as much as possible.

In the consultation room, much can be done with minimal handling and in the base of the carrier (Figure 3) to complete examinations and perform various procedures (such as blood pressure measurement).

Anxious cats may need breaks, and some may prefer to hide their heads in the blanket during examination.

Treats can be offered, but some cats with fear-anxiety may not be interested. Through this process of interaction, an assessment can be made of the cat’s emotional state and, if further procedures are required, sedation may be preferable for those exhibiting ongoing fear-anxiety.

In many cases, if further procedures are required, sedation can be quicker than multiple attempts, for example, to obtain a blood sample from an increasingly anxious cat, and mitigates the impact of fear-anxiety on future visits. More information on interacting with cats in the clinic is available in 2022 AAFP/ISFM Cat Friendly Veterinary Interaction Guidelines (tinyurl.com/yydsvpf2).

Many practice systems allow you to add a warning on the patient file, such as “care” or “animal bites”. This is unhelpful when considering how to approach a cat with fear-anxiety.

Instead, recording information on the cat’s emotions and behaviour, what worked and what did not, and dosage and type of anxiolytic that was effective, is vastly more helpful to the next person seeing the cat; for example, “likes to hide head in blanket when examined” or “pregabalin (5mg/kg PO given 2 hours before appointment) very effective and could take bloods”.

A reminder or pop-up appearing when the file is opened could prompt reception teams to ask if an anxiolytic should be dispensed when the cat is booked for an appointment.

While we cannot remove all anxiety from our feline patients, we can identify anxious cats and help them and their caregivers access the veterinary clinic.

Using anxiolytics can make a huge difference, but these medications are not a substitute for an environment that considers the cat’s senses and gentle handling.

A combination of pharmacotherapy (including sedation and analgesia, if needed) and cat-friendly handling can minimise protective (negative) emotions and optimise patient well-being.

Pregabalin has been used to reduce anxiety and fear associated with transport and veterinary visits5.

A veterinary licensed product, Bonqat (Dômes Pharma) is available in the UK as an oral 50mg/ml solution, and 5mg/kg should be given 90 minutes before transportation. The dosage can be reduced in cats with chronic kidney disease, but this has not been specifically studied. Sedation and ataxia may be noted7, and cats should be kept indoors or away from stairs or drops until recovered. No studies directly compare pregabalin to gabapentin, but pregabalin may be less sedative than gabapentin.

Gabapentin has also been shown to reduce stress and improve tolerance of handling in the clinic4,8. Protocols commonly used are to administer 50mg/cat to 100mg/cat by mouth (or 20mg/kg) orally two to three hours before putting in the carrier. A lower dosage (for example, 50 per cent reduction) should be used in cats with chronic kidney disease and for debilitated patients9. Tablet sizes suitable for cat and liquids are available from specials manufacturers in the UK. Caregivers should be warned that their cat may be ataxic for several hours after treatment and should be kept indoors and away from stairs until recovered.

Trazodone is a serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor, and may cause sedation. Some studies have shown benefit in facilitating veterinary examination6, although this was not replicated in another study10. Dosages of 10mg/kg by mouth two hours before transport have been recommended. In some cases, combining trazodone and gabapentin (trazodone 5mg/kg to 10mg/kg and gabapentin 20mg/kg) could increase anxiolytic effects. Top tips for using anxiolysis in cats include the following.

The whole team, including vets, nurses and reception staff, can make a difference to an anxious cat (and caregiver).

Reception and client care staff are particularly important, as they have initial contact with the caregiver, who may report concerns about bringing in an anxious cat. When registering new patients, they can provide information on carriers and travel to the clinic (see tinyurl.com/y9pda2m9), and ask if the cat has been anxious at previous visits and note any concerns. This can be recorded in the notes and passed on to the vet, if needed for prescribing anxiolytics, for example.

Additionally, the reception team can send a new client form to collect more detailed history (for example, see tinyurl.com/ysc7wyne) prior to the visit.

For existing patients, behaviour in the clinic can be recorded constructively by the nursing and veterinary team. Nurses play a key role in identifying anxious cats in consults, during procedures and in the ward, and learning what works for each individual cat, and when further intervention (such as sedation) may be needed.

International Cat Care’s emotional health chart for hospitalised cats can be completed by the nursing team alongside pain scoring tools (see tinyurl.com/mw4hxbfv and Figure 4) and all cats (anxious or not) should have somewhere to hide if hospitalised (Figure 5).